21

“DID YOU PICK THIS ROSE FOR ME YESTERDAY, AND BRING IT UP?”” LUCY, clutching a warm towel to her, rose from the bath and examined the delicately fading bloom more closely. It was scented and colorful, but now that she looked more closely, she saw it was perhaps slightly rain-damaged. “You should have done it today, the twenty-first—for the spring equinox.”

Alex appeared beside her from the adjoining room, the bathroom serving each of the brothers’ bedrooms from either side. “No, I thought you must have. I was amazed you’d found one so early in the season.” Alex shook his head. “You make me wish I’d thought of it—though I doubt there’s anything in flower yet. Who’s been here? Perhaps someone borrowed the house.” He stepped closer and studied the flower properly. “Actually, it’s faded, isn’t it? Beautifully preserved. As though it were touched by frost on the bush.”

“It has a wonderful myrrh fragrance, though. Can it have been picked long ago?”

She returned to the bedroom without waiting for his answer, and found the shutters thrown back, and a window open. Alex had brought a breakfast tray up with a teapot and brioche. “Are you drinking my brew now?” She laughed at him. “You’re spoiling me. I’ve got to go back to the real world tomorrow and put in rather a long day.”

Alex wondered a little what that “real world” might consist of now, but answered Lucy with a deliberate lightness: “Like the rest of us then. We’ll need a flight around four. I’ve got to return the car first, and pay the excess. We should have an early lunch.”

“I wish we never had to leave here.” Lucy easily sensed Alex’s train of unspoken thought. “It feels safe: as though it’s got its arms around me. And the linen smells of lavender…”

She had been deeply affected by coming to this, Alex’s mother’s house, and felt she’d found something she never realized was lost to her. Despite the tensions they had been through, the place itself worked like a love philter on them, and made her feel relaxed, and whole, and healed, in Alex’s presence. She dropped her towel and walked to the window, forgetting the compulsion to cover her scarred body for the first time in months. With the victory of sunshine over the rain there was a double rainbow.

“Look, Alex.”

He joined her, putting his arms around her from behind and leaning into the windowsill. “Poetry, and science.” His eyes smiled at her. “You must see the garden before lunch.”

“Let me cook for you today,” she offered; and Alex didn’t protest.

The grass was soaked, and a few small branches littered the orchard, but there was little damage from the storm. Lucy looked at a hundred rosebushes coming into bud, tiny shoots alive everywhere, but no proper blooms yet. She fingered the spiral in the fountain which was set at the heart of the beds, and Alex explained it was his mother’s handiwork. The water was overflowing, freezing; but she scooped some out and looked at the depiction of Venus in the center. On a stone wall forming a windbreak behind the flowers Lucy noticed a sundial—an ancient arm of iron pointing its finger back at Venus. There was enough sunshine to check its accuracy; and she looked at her watch like a little girl proving a mystery. She screwed up her nose when it wasn’t right, and Alex laughed.

“It’s been calibrated as a moon dial. My mother was called Diana, like the goddess of the moon; and she loved moonlight. For a while she used the sundial in the other part of the garden, and we used to have to make adjustments—I recall forty-eight minutes of correction for every day either side of the full moon, when midday was accurate to midnight. But thereafter you had to do a lot of math. So this has the corrections set into the brass.”

“How magical. What a wonderful mother you had.”

Alex nodded. The sadness Lucy discerned on his face was less about the loss of his, more about his empathy for the absence of hers during her life. But he deferred mentioning it to her for another day. “Shall we walk in the orchard?”

As she stepped away from the moon dial’s domain, she trod on a loose tile set in the ground, with a large star on it. Alex heard the click. “All this needs repair. If I can get down here for another long weekend in good weather I’ll try to give it a tidy up. I’ll bring Max to help. Would you put on gardening gloves too?”

“You know the answer.” She appreciated the inclusion with his son, took his hand, and walked toward the grove of trees. When the grass became long, wet, and tangled, he piggybacked her. She thought about her drugs, wondered if she was hallucinating. But Alex was there, smelling of the vetiver top note of Acqua di Parma and the earthiness of wood smoke; and she kissed his neck.

HE TELEPHONED MAX—WHO WAS DRAGGING SIÂN TO ALL OF HIS FAVORITE pleasure spots—while Lucy cut shallots and lemons and arranged the St. Peter’s fish from yesterday’s market in a dish. The kitchen was lovely to work in—good light and space, properly equipped, a huge variety of herbs. She put the fish into the oven and set the steamer whirring with some rice, then picked up her water glass and strolled back into the living room, walking straight to the piano. Alex had explained it was effectively Will’s; and she wanted to touch it. It was years since she’d played, though she’d once been quite good, but she needed to know if she could pick it up again. She glanced at the music on top and gulped.

“Will you try it then?” Alex rejoined her.

“This is a bit out of my league. The Waldstein, Schubert Impromptu…all this impossible Chopin. Not one simple nocturne in sight. Was he this good?” Alex nodded his head decisively, and she shook hers: “I’ll have to practice then.” She moved the cello, and glanced suddenly at Alex. “This was yours. Property of the god Apollo.” She laughed, but it wasn’t put as a question.

“I’ve given up now. No time. We played trios together—and I was the weakest. But my mother was a first-rate fiddler. When she got too ill to play, I stopped altogether. Will would always play for her. He’d spend whole days there when it rained. I don’t suppose she was ill, the last time we all played here.” His words lost volume and clarity. “Please, make some music. It’s sad for it to be silent. It’s a lovely instrument.”

“Don’t expect too much.”

She said this self-consciously, but she desperately wanted to play. She looked at Alex long enough to form a thought, then sat; and her hands sure enough found their way without embarrassment. Alex listened: she played Debussy. Not an especially difficult piece, well within her range; but she performed with great feeling. What affected him was her choice. It was short; and he nodded approvingly when she’d finished.

“‘La fille aux cheveux de lin,’” his voice trailed. “‘The Girl with the Flaxen Hair.’ Will used to call it ‘The Girl with Horse’s Thighs.’” Lucy laughed. “I forgot how pretty it is. Can I hear it again?”

She was happy to comply; and the years eroded. It was his wedding day; he was marrying Anna, whose hair Will had said was like “wind in the cornfields.” He’d played this piece for them in the church of Anna’s Yorkshire village, told Alex to hold very tight to her if he really loved her. Alex found himself wondering what Will might be telling him now, through Lucy—not to repeat the mistake and lose hold of her? Her hair was dark silk and she couldn’t have been physically less similar to Anna, but he felt the thinness of a veil he’d never have imagined even a day ago, and it surprised him. He walked over to her and kissed her hair. “Thank you.”

LUCY WAS SCRAPING PLATES AND ALEX TYING UP FISH BONES IN THE rubbish when his cell phone rang. He was regretting switching it on today, but he couldn’t get back to the hospital, so he gave her a sanguine look and answered it. “Alex Stafford.”

“This is half. We’ve been right through it, and half of the pages are missing.” It was the voice of Alex’s verbal fencing partner on Friday night, with its slightly assumed Kentucky-sounding lilt.

“I have no idea what you mean. That’s everything I have. Perhaps you’d like to check in the books you undoubtedly relieved us of.”

“Then you haven’t found it all. The ultimate sheet here is clear: ‘halfway through the orbit.’ This is half the documentation. I imagine the rest is the writing we’re really looking for. Now think for me, Dr. Stafford: a lot depends on it. Where would the rest be?”

“What is it you’re hoping to find? The hem of an angel’s robe?”

“Mockery sits too lightly with you, Dr. Stafford. Consider the equation I’ve just put to you. You know me already for a man who’ll go after what he wants. I’ll call you this time tomorrow. Have an answer.” He hung up.

Lucy searched his expression, had heard some snatches of the voice, knew at once what it implied. “Did you give them everything?”

Alex nodded. “All the originals. I still have the set of photocopies I made for you to work from to preserve their age. I left nothing out for them—that I know of.”

“How nervous should we be of these people, Alex?”

“I wish I knew.” He hesitated. “You’ve had excellent instincts about all this so far. Do you get the feeling there’s more?”

She took off her rubber gloves and leaned against the sink. “You still haven’t told me about the answer you arrived at from Will’s first sheet. You told me you’d cracked it too—I would guess rather differently from my own take on it?”

Alex took her hand and led her to the bookshelves in the hall. “Can you find a Bible?” They both hunted, and she came up with a slightly worn cover that was inscribed inside for Alex’s Christening, “Palm Sunday, 1970,” from his godparents. “Yes, good—it’s a King James.” She followed him to the sofa and Alex talked her through it.

“Like you, I got the first part as: ‘Will, I am.’ I assumed it meant that it was for Will. Then I started thinking about someone whose alpha and omega were the same day; and I thought straight away of Shakespeare—the period was right, and the given name. So I checked, and I was right to remember he was probably born on April twenty-third, and he died that day too; so it seemed a chance. I thought of the ‘song of equal number in the Old King’s Book’ and decided it might be Psalms, after the Song of Solomon yielded nothing. So I tried the famous Psalm twenty-three, and looked at it, and played with the counting in it: nothing. But look what happens if you double the number twenty-three, to make of the two halves—or ‘birth day’ and ‘death day’—a whole number.”

“Forty-six?” Lucy flicked through to find Psalm 46, and they looked at each other as a folded piece of palm, wrought into the shape of a cross, came free from the fold of the page. “They make these on Palm Sunday. Has it been here since your christening?”

Alex shook his head in disbelief. “Curious…marking that place. Count the same number of paces forward from the start: and tell me what you get.”

Lucy’s nail counted forty-six words from the start, and she looked at him half smiling: “‘Shake’? You’re not going to tell me that if I count the same number from the end…?”

“Omit the exit word, do you remember? It’s ‘Selah’ in this copy; but it’s ‘Amen’ in the one at my flat that Will had packed in his rucksack.”

Lucy followed instructions, trembling as her finger hovered over the forty-sixth word: “spear.” “Alex, you’re a genius. But is this for real?”

“Do we agree, the whole message yields ‘William Shakespeare’—who was, incidentally, forty-six years old when the King James was printed?”

“‘Is’t not strange, and ten times strange?’ Is it a deliberate code?”

“My feeling is that Shakespeare is implicated in the documents—how, I can’t imagine. But it doesn’t help with this question of ‘more,’ does it?”

Lucy sat glassy-eyed for a moment. “Did Will get this far?”

“Maybe you know?” Alex was teasing her, but without malice. “I would love to discover what he did with his hours after he visited the cathedral and walked the labyrinth. Messages he left me suggest he had things to say; and when I went through his effects, the card from Chartres was there—the one my mother left him about the venison—along with a brasserie lunch receipt, and he had his hair cut; he’d sketched a stag, or a deer, on a small sheet of artist’s paper; and you know he ordered Siân some flowers a little before three. But the ferry didn’t leave until very much later. What was in his head in the intervening hours?”

Lucy looked at him. “I wish I could tell you, Alex. I’m not Will. I just have a rather resonant piece of him with me. But if my instincts are anything, I’d say a few things seem particular. These flowers he ordered Siân—did you say before they were roses?”

“White ones. For her birthday—which was still a month off.”

Lucy nodded. “I smelled roses in the labyrinth—probably the perfume you gave me wafting back in the warm air; but maybe that’s a phenomenon of the labyrinth too—or maybe not. Could that rose upstairs be six months old? Would it fade so perfectly? Might it have been here when Will was?”

Alex shrugged. “Possibly he picked it, you mean?”

“That was the autumn equinox. So, there’s an equinox rose, the venison. And the stag. That’s interesting, don’t you think? Isn’t the hart a device of Diana the moon goddess?” She wasn’t waiting for his answer. “And there was a hart on the bodice of the woman in your miniature—the painting. I’d say Will might have come back here. Is it on the way to the ferry?”

“Ish. What are you thinking?”

“Was your mother signposting him?” She looked at him seriously, suddenly struck with an idea. “What was the wording of her legacy to him—with the key?”

“Something like: ‘For Will when you’re someone you’re not now…’” And Alex followed her thoughts. “I suppose that’s you now, Lucy. If you think like a poet instead of a scientist. Perhaps the key really was meant for you.”

“They took the gold copy you had made for my birthday.”

“No matter. When we get home, you must have the original silver one again.”

“We’re part of this riddle, Alex. You and I are supposed to solve it. Didn’t Alexander cut the Gordian knot, or something?”

He laughed. “Oddly enough, our family insignia is a knot: for the Staffords. I think my parents were having a quiet joke when they named me Alexander. It’s been part of the Stafford heraldry since at least the fifteenth century. But that’s not my mother’s side of the family.”

“Yet the Staffords seem to be included in the mystery somehow. A Stafford was the ambassador to France at some point during the reign of Queen Elizabeth. He was the contact with the Hermeticist Giordano Bruno, who was burned at the stake in no less a place than the Campo de’ Fiori—the ‘Field of Flowers’—which is what that very first document Will was given must be referring to, and I think Will realized it. I read about it while researching Dee, and I think Simon mentioned it too. The connection with the Stafford name struck me. I’ll check my notes. I’m wondering if he was a relative.”

Then she looked at him with a flash of insight. “The knot garden. The roses. The moon globe. Diana’s realm. Let’s take a look.”

Lucy’s finger looped along the spiral Diana had created in her fountain. Made of mirrored glass, it picked its shiny path through a pattern of blues and ruby reds all mosaicked from broken china plates so carefully color-matched that Lucy realized they’d been purposely broken. The fountain was shallow, edged with shells; and Lucy was reminded of the Lady of Shalott working in reflections to weave her embroidery, as the silver shards reflected the sky and the landscape all around it. She traced the route to Venus in the center, and thought of Alex’s gentle fingers curving along her scar around her breast, circling her heart. The motion itself was sensual, mesmerizing, a gesture of mystery.

She turned to him to say something, but he was lost in thought, looking at the altered sundial, and she hesitated. He read her empathy, and invited her into his mind.

“The sun doesn’t preside here. Its vitality is essential for the roses; but even at midsummer, when the smell is overpowering, my mother would bring me out long after the shade had deepened to prove that the scent was strongest, most alluring, in the evening. All the flowers are night-scented. Under the moon’s light the white roses are luminous, almost palpably so. The moon dial makes it midday at midnight. The fountain reflects down the stars: a fragment of heaven on earth. The spirit of this garden is female. My mother created this space to express another view of the world, and subvert the norm. The sun is consort, and a vital partner, but not the sovereign lord. It wasn’t enough for us to understand it cerebrally: she needed us to witness it.” He turned to Lucy. “Maybe because hers was a house of men.”

“She seems to have held her own.”

“Yes. But it was something she cared about. From prehistory, before the male role in procreation was understood properly, women were the bearers of the secrets of life and death—because they could bring forth life without any properly explained male contribution. They were understood to have an innate knowledge of the mysteries of the gods, to be the initiates of divine wisdom. Then there was a shift toward a more male, Apollonian, rational view of the world, downplaying mystery and the dreamy, lunar, female aspects of religion. The sun god, Apollo, brought clarity and an appreciation of what was knowable rather than inexplicable. Dionysus was the god of ecstatic visions and the rite of the moon.”

“You and Will,” Lucy suggested.

Alex laughed. “In some ways. But Mum hoped that a marriage of clarity with mystery was not incompatible, and that the best understanding of the world would come from it. Possibly she thought that she and my father—in some respects—embodied this.”

Alex said no more, but Lucy understood it all, and she walked over and took his hand. “If I could choose a mother, yours would be my choice,” she said with feeling; and Alex was touched. She looked up at the talon from the clock pointing back at Venus’s watery haven, noticed it was showing a time, by chance, of between three and four o’clock, when it should have been at least an hour earlier.

Alex followed her gaze. “Much more than forty-eight minutes out now.”

Lucy thought about Alex’s mother in the light of this garden. “Did you know that Botticelli painted the Primavera, and the panel of Venus and Mars, to draw down the magic of an exact aspect from the planets, to breathe the harmony of the heavens into the onlooker? Your mother must have known that the individual human being, as microcosm of the universe, was believed to express the whole of creation and the whole of the divine.”

Alex heard her; but Lucy’s attention had moved to the shadow from the clock. It was the spring equinox—within a day—when the balance of male and female, sun and moon, day and night, was equal. A celestial marriage. She was thinking what a perfect moment that was for them both here at the house—“a consummation devoutly to be wished.” It could be about this inaccurate time—around four o’clock—just before dawn, the last hour of the moon’s light, before the first breath of sunrise at the equinoxes. “Alex, look where the shadow happens to fall.”

The true time was only a shade after two, but the finger of shadow touched the star tile which Alex had said earlier needed repair. He leaned down and reexamined it; and this time its looseness attracted him. Lucy took her hair down and gave him her heavy clip to prize the edge. The tile came away from its lodging place with little effort, and they found a space underneath it, a deep hollow, with no object below it.

“Something was here, unquestionably.” Alex looked at Lucy in bafflement. Here was territory he had no map for. It suggested that for years his mother had created this secret place with a deeper agenda he’d known nothing of. Some object had nestled under the star, to a depth of roughly an old-fashioned English foot. It was enough to hide an upright box, or a bottle.

“Someone got here first,” he suggested.

Lucy reached across Alex’s right hand, his fingers still grasping the top of the tile. She closed her fingers over his and inverted it, the underside now faceup. They locked eyes, and smiled.

“Will.”

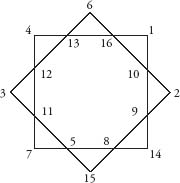

On the reverse of the tile was a second star—squared and petal-shaped—painted carefully, dotted with numbers, with some words below. It had been fired to preserve it.

Under the star were the Italian words: E quindi uscimmo a riveder le stelle. And in the very heart of the space, a key was taped. The spare to Will’s Ducati.