The study of Neanderthal behavioural ecology is a relatively new field and so far hasn’t generated a great deal of interest among researchers. And yet, because species are products of their environment, a detailed study of the nuances of the Neanderthals’ environment (as inferred from the archaeological and genetic evidence) may answer important questions about how they behaved, what they looked like and why they emerged as a separate species. The kinds of questions this discipline tries to answer include: Did Neanderthals interbreed with early humans? What did they look like? Why are Neanderthal genes so conspicuously absent in modern humans?121,122 How smart were they? Then there’s the big question: What caused their extinction—a subject that currently generates countless theories but no consensus.

But perhaps the most important objective of my reassessment of Neanderthal behavioural ecology is to shed some reflected light on human evolution. NP theory is actually a theory of coevolution—the synchronistic evolution of two sibling species living close to each other— so discovering how the environment shaped Neanderthals may also tell us how Neanderthals shaped humans.

Another objective of this reassessment is to correct what I believe to be a distorted anthropocentric bias that has inculcated western thought on all things Neanderthal. Instead of seeing Neanderthals for what they were, a unique and complex species inhabiting a particular ecological niche, it has been assumed they were essentially a mirror image of ourselves— albeit, not as smart. Perhaps, like children discovering they have a sibling they’ve never known, we harbour an unconscious longing for some kind of meaningful connection—a reunion of sorts—a sense that we’re not alone in the universe. But this oversimplification robs us of the detail— the nuances which conceal the greatest truths. Neanderthals may be our doppelgangers but, until we stand them side by side with other primates and make the objective comparison, we’ll never know for sure.

Although the reassessment is consistent with the latest archaeological findings and genetic data from extracted ancestral DNA, some aspects of it are speculative and rely in part on circumstantial evidence (which I will duly note). Fortunately, advances in palaeoecology and genetics over the last few years provide a solid support for the reassessment.

Neanderthals were a species of hominids who lived in Europe, west- ern Asia and Britain (which was then a peninsula of northwest Europe, thanks to sea levels being 80 metres lower than today). It is believed they became extinct about 28,000 years ago, although some dates suggest they survived until 24,000 years ago.

NEANDERTHAL OR NEANDERTAL?

The word itself comes from Neander Thal (which means ‘Neander Valley’ in German) where the type specimen (Neanderthal 1) was discovered in 1856. With no ‘th’ sound Germans pronounce it Neandertal, while in English, Neanderthal, with the softer ‘thal’ has become widespread. Neanderthal is more commonly used today, but either word is acceptable.

Until recently, Neanderthals were thought to be the same species as us. But over the last decade, geneticists have extracted DNA from ancient Neanderthal bones which, when compared to human DNA, shows conclusively that although Neanderthals were members of the same genus as us—Homo—they weren’t human.123,124,125 The DNA variation was enough to conclude that Neanderthals were a separate species.

Geneticists are divided about when Neanderthals split from the human ancestral tree. Estimates vary between 350,000,126 370,000,127 500,000128 and 631,000 to 789,000 years ago.129 In other words, for maybe half a million years, they were off on their own evolutionary trajectory—forged and shaped by the environments they inhabited during this period.

Although they were slightly shorter than the Skhul-Qafzeh humans, (which probably helped conserve energy in cold climates), the remains of a few tall Neanderthals have been found. In the 1960s, a Japanese expedition excavated an almost complete Neanderthal skeleton at Mt Carmel in Israel. What was extraordinary about this adult male (known as Amud 1) was that he was almost six feet tall—an exceptional height in those days—and ostensibly a giant who would have towered over early humans of the period.

Despite usually being slightly shorter, the average Neanderthal was much stockier, weighing about 25 percent more than a human. They were so heavily muscled, their skeletons had to develop extra thick bones and attachment points to take the strain. With massive barrel chests, arms like Arnold Schwarzenegger and legs like telegraph posts, it has been estimated Neanderthals were about six times stronger than modern humans.

“One of the most characteristic features of the Neanderthals,” writes palaeoanthropologist Erik Trinkaus, “is the exaggerated massiveness of their trunk and limb bones. All of the preserved bones suggest a strength seldom attained by modern humans.”130

James Shreeve, author of The Neanderthal Enigma, adds that, “a healthy Neanderthal male could lift an average NFL linebacker over his head and throw him through the goalposts.”131

It wasn’t just Neanderthal adults who were bigger, stronger and burlier than modern humans. Their children were too. “You should see some of the skeletons for these individuals,” anthropologist John Shea told Discovery News. “The females were big and strong, while a 10-year-old kid must have had muscles comparable to those of today’s weight lifters.”132

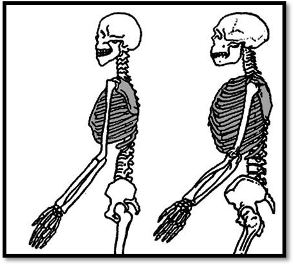

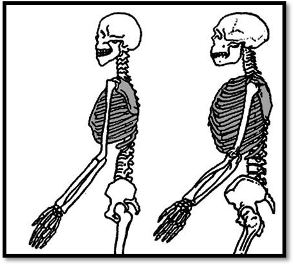

The larger, more robust rib cage of the Neanderthal (right) is indicative of far greater upper body strength compared to humans (left). It is more analogous to modern gorilla physiology than that of humans.

On the basis of their stone weapons and tools, preserved remains of the animals they hunted, and the way they processed carcasses, it is now generally agreed that Late Pleistocene Neanderthals were skilled hunters rather than opportunistic scavengers.133,134,135,136 A great deal of research, particularly over the last decade, has recognised the cognitive and behavioural complexity of Neanderthals.137,138,139,140,141 As one study of Neanderthal hunting techniques concludes, “although Neanderthals and modern humans differed in salient ways, the vast behavioural and cognitive gulf that was once thought to exist between them has now narrowed considerably.”142

Although Eurasian Neanderthals and Levantine early humans inherited similar features from common primate and hominid ancestors, the different geological and climatic ecosystems they inhabited for hundreds of thousands of years gradually selected for physical and behavioural differences. We know the coastal environment of the Levant during the Late Pleistocene resembled the African savannah, with over a hundred differ- ent varieties of edible plants, so it is not surprising that Levantine humans retained the adaptations they had acquired in Africa over the preceding six million years. That included their omnivorous diet and a preference for savannah habitats.

In contrast, Neanderthals evolved in ice-age Europe, the only hominid species to evolve in a climate of seasonally lethal cold.143 During their half-million-year occupation of Europe, they gradually acquired a range of physical and behavioural adaptations to protect themselves against the cold. One of the main adaptations to the periglacial environment, which has been described as one of the harshest and most inhospitable habitats ever occupied by hominids,144 was the adoption of a high protein animal meat diet. Steve Kuhn and Mary Stiner, from the University of Arizona, say that few plants could survive in that cold climate and that those that did were not nutritious enough, or required too much effort to collect and process relative to their low nutritional yields.145

Because of their considerable weight and energy expenditure, not to mention the need to maintain body temperature within functional levels, Neanderthals had to regularly find and consume enormous amounts of protein which was converted to body heat. It has been estimated the average Neanderthal consumed about 1.85 kg (4.1 lbs) of fat-rich meat every day.146 That’s equivalent to the meat in 16 McDonald’s Quarter Pounders. Early Neanderthal scholars assumed they were simply dumb cavemen who probably scavenged most of their meat from other animals, but we now know this was not the case. In fact, there are no exclusive mammalian scavengers. That is because the time and energy it takes to scavenge enough food is simply too high compared to hunting. And most predators vigorously defend their kills, so a scavenger is always at risk from being injured or killed.147

All this leads to the conclusion that Neanderthals were not scavengers. As Erik Trinkaus explains, “Neanderthals were not randomly wandering around the landscape, stumbling on an animal they could kill or a carcass they could scavenge.”148

Only fresh meat could provide Neanderthals with the high protein, energy-rich diet they needed to maintain their large body mass and energy expenditure. Because fishing wasn’t practised in the Middle Palaeolithic,149 and there is no evidence of Neanderthal fishing technology, the only way they could have obtained a constant supply of fresh meat was by hunting terrestrial prey.

Just as modern Inuit residing in glacial habitats have adopted a high protein diet of animal flesh, European Neanderthals abandoned the omnivorous diet of their African ancestors for a carnivorous diet of animal flesh. Such a fundamental switch in their diet would create a substantial ecological divide between the Neanderthals and humans. When European Neanderthals abandoned their hunter-gatherer lifestyle and became hunters, their whole evolution was focused on becoming better hunters. And that, I suggest, had profound implications for human evolution.

You might think it would be virtually impossible to tell what your average Neanderthal ate for breakfast or dinner 100,000 years ago but that is not so. Researchers have discovered that the chemical composition of animal bones is affected by what they eat. When geneticists began analysing isotopes of bone collagen in Neanderthal bone specimens, they found that the Neanderthal diet consisted almost entirely of meat.150,151,152 In one French study, calcium ratios extracted from 40 Saint-Césaire Neanderthal samples revealed the Neanderthal diet was composed of about 97 per- cent (in weight) of meat.153 These and similar findings are summarised by English palaeoanthropologist Paul Pettitt who concludes that Neanderthals ate “meat for breakfast, lunch and tea”.154

By comparison, even though our African ancestors who migrated into the Levant were hunter-gatherers, the reality is that they were not so much hunters as gatherers. The fossil evidence tells us that early humans resolutely maintained their African omnivorous diet, which consisted mostly of gathered food—berries, roots, tubers, fruit, nuts and plants. In fact, the majority of their energy intake was supplied by uncultivated fruits and vegetables.155 Analysis of Middle Palaeolithic human remains shows that archaic humans had only limited hunting abilities, captured only small to medium-sized or weak game, avoided dangerous prey and supplemented their diet by scavenging.156,157,158,159,160 Even today, modern hunter-gatherers such as the !Kung people of the Kalahari Desert obtain only 33 percent of their daily energy intake from hunted animals.161

Although diet may seem an inconsequential matter in the great panoply of events and circumstances that led to the evolution of our species, in reality, how a species evolved its unique diet and acquired the adaptations to maintain it successfully has far-reaching evolutionary consequences.

Social predators (predators that hunt cooperatively in packs) use their own claws, talons, teeth, stings, poisons and beaks to disable and kill prey. Neanderthals represent the rare example of a predator intelligent enough to hunt collectively and use complex weapons.

Ample evidence exists to show that Neanderthals and their Middle Pleistocene European predecessors were practised in using stone-tipped wooden spears to hunt prey.162,163,164 In Lehringen, Germany, the broken tip of a Neanderthal spear was found still embedded in the ribs of an elephant skeleton, while at Umm el Tlel in Syria, a Neanderthal spear point was recovered from the cervical vertebra of a horse.165

Neanderthals did not hunt rabbits, rats, hedgehogs and other small game. We know from the bones littering their caves that Neanderthals were using their flint-tipped thrusting spears to bring down the largest and most dangerous species in Europe—woolly mammoths, giant cave bears, woolly rhinos, bison, wild boar, wolves, antelope and even cave lions.

Back then, these animals were considerably larger than their modern- day equivalents. The Eurasian cave lion stood 1.5m tall at the shoulder, about as tall as a Neanderthal. The animals the Neanderthals were attempting to kill were among the largest and most dangerous on earth. We must presume they mustered up the courage to hunt them because there was no alternative. Only these large mammals provided enough of the high protein meat they needed to survive. If they couldn’t bring them down, they would starve.

The wild animals that roamed the glacial tundras of ice-age Europe not only fed and fuelled Neanderthals, they moulded them. Their ferocity, their will to live, their own acquired lethality raised the bar and forced Neanderthals to become tougher, smarter and more aggressive. These wild beasts helped transform Neanderthals from a docile African hominid to the fiercest European predator.

While courage does not fossilise, we need to at least briefly consider how important it was to Neanderthal survival. The major animals Neanderthals hunted were physically larger, stronger and tougher than them. Some were predators themselves. What courage would it take to attack a towering mammoth, or a cave lion, or a woolly rhino, approaching close enough to stab it repeatedly with a stone-tipped spear—while it was desperately flaying with its horns, teeth, talons or claws—and to keep attacking until the thrashing beast was finally stilled?

Courage was not the only essential attribute. Natural selection also favoured the smartest individuals—the ones who survived because they could fashion weapons and use them to gain a strategic advantage, to outwit and out-manoeuvre animals ten times heavier.

Just as wolves, lions, hyenas and other carnivorous pack-pursuit predators evolved specialised sensory, behavioural and physiological adaptations that increased capture rates and improved killing efficiency, so too would Neanderthals acquire and hone similar predatory adaptations. In other words, hunters evolve to become more efficient and lethal. They acquire increasingly refined adaptations to locate, stalk, track, capture and kill their preferred prey—whatever it is. Being a predator defines its own evolutionary path.

High intelligence, guile, cunning and stealth only emerge at the pointy end of natural selection—the dangerous prey that killed off thousands of early Neanderthal hunters gradually shaped them to be the best predators they could be—relentless, stoical, ingenious, duplicitous and able to detect and interpret the tell-tale signs and scents of their quarry. Gradually, the gored, gutted, torn-apart, trampled-on individuals who lost their lives in the hunt gave way to a new breed of super-smart, hyper- aggressive killers.

A final line of evidence that Neanderthals evolved as a predator species is the thickness of their skulls. These were unusually chunky— at least compared to those of early humans. This chunkiness is called postcranial hyper-robusticity and has been interpreted by Valerius Geist, from the University of Calgary, as an adaptation to close-quarter hunting confrontations with large mammals.166 It is another one of those things that gets selected—over time only the thick-skulled Neanderthals survived. Just as over time the demands of predation bestowed on Neanderthals their massive trunk and limb bones and their exceptional strength.167

An accepted method of testing scientific theories is to generate predictions from the theory and test them empirically. If Neanderthals were carnivorous predators engaged exclusively in hunting large, dangerous animals, this generates several predictions that can be tested. For a start, life at the top of the food chain would not have been easy, so Neanderthals would suffer more physical injuries than early hunter- gathering humans. This violent lifestyle would also mean that they did not live as long as humans. Both these propositions are corroborated by a plethora of scientific evidence.168,169,170,171

Judging by the high frequency of bone fractures in Neanderthals,172,173 their close-quarter encounters exacted a heavy toll in physical injuries. In his study of trauma injuries among Neanderthals, Erik Trinkaus found that almost every adult Neanderthal skeleton ever examined reveals some evidence of skeletal trauma.174 In one examination of 17 Neanderthal remains, Trinkaus found 27 skeletal wounds. And there would have been many more soft tissue injuries that were not preserved. While some of these injuries may have come from interpersonal violence,175, others must have been suffered in the course of predatory encounters.

On the basis of microscopic and chemical analysis of their bones, scientists have been able to estimate how old each Neanderthal was when they died. From this data, it has been established that Neanderthals rarely lived beyond the age of 40, which is considerably less than Upper Palaeolithic modern humans.176 Life at the top of the food chain was incredibly tough.

A picture begins to emerge of Neanderthals, not as the popularly portrayed dim-witted scavengers, but as cunning, formidable predators— two-legged, big-brained versions of lions and sabre-toothed tigers—and, like other top-level carnivores, possessing specialised hunting strategies to maximise their killing efficiency. John Shea provides an apt conclusion: “Once seen as dull-witted cavemen, new evidence indicates Neanderthals were intelligent, adaptable, and highly effective predators.”177 Elsewhere, the Stony Brook University anthropologist describes them as the “superpredators of the Ice Age”.178

For a species that evolved in the frigid wastelands of ice-age Europe and survived that punishing environment for 500,000 years, being tough, stoical, resilient and aggressive was part of a tried and tested survival strategy. These attributes are the hallmarks of a top flight predator which, in conjunction with their amazing predatory prowess, allowed the Neanderthals to claim the position at the apex of the food chain. In Europe, Neanderthals became the perfect predator. And when some of them migrated to the Levant (to become the Eurasian Neanderthals) they brought with them all their predatory skills and attitudes—the whole gambit of their ferocious lethality.