Predation forces carnivores to expend considerable amounts of time and energy hunting. Because most prey species are easier to catch at night when they’re resting, the majority of mammalian

land predators hunt nocturnally. Research has also shown that scents can be detected over greater distances at night—further encouragement for predators to hunt nocturnally.331 Most of the hunting by lions in the Etosha National Park in the Serengeti, for example, takes place under cover of darkness.332

It is possible then that, in addition to daylight hunting, Neanderthals also adapted to nocturnal hunting during their European sojourn. This hypothesis, which has implications for both behaviour and physiology, can be examined by extracting several firm predictions from it and testing them empirically.

The first prediction of the nocturnality hypothesis is that, like other nocturnal hunters, Neanderthals would have acquired specialist physical and behavioural adaptations common to nocturnal predators. For a start, we would expect them to acquire specialist eyes able to locate prey under low-light conditions

Secondly, because nocturnal mammalian predators rely to a far greater extent on scent to locate and track prey than do daylight hunters, they tend to have more developed olfactory organs.333 As there is a direct relationship between an animal’s ability to smell and the size of its nose,334 this predicts that Neanderthals acquired additional sensory detection receptors (called olfactory neurons) to detect and process scent molecules. Theoretically, this would result in a larger nose.

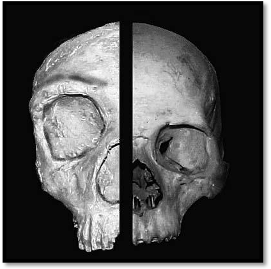

Ostensibly, this prediction seems almost impossible to prove because noses are made of soft tissue which does not normally fossilise. However, the size of the nose can also be measured by the nasal aperture in the skull, and even a cursory comparison (above) between a Neanderthal skull (left) and a modern human skull (right) graphically reveals that the Neanderthal nasal aperture is considerably larger than in humans. This raises an interesting new question. In other animals with a keen sense of smell, the extra olfactory neurons are housed in a protruding snout but, if Neanderthals retained a flat nose as an adaptation against frostbite, where were the extra olfactory neurons, membranes and epithelial tissue placed? Anatomically, there’s only one viable option—they had to be accommodated internally, just behind the flat nose.

This provides a prediction that can be tested. It claims that the enlarged olfactory organ required by their nocturnal lifestyle would result in the midface area around the nose extending out to make room for the extra olfactory neurons, turbinal bones and epithelial tissue. It’s what’s called midfacial prognathism. In all likelihood, the tip of this ‘snout’ would have a patch of moist black hairless skin around the nostrils called a rhinarium which would increase sensitivity to smells.

These adaptations would create the impression of a kind of moist, protruding muzzle—like a dog’s—quite different from the flat face of early humans. Obviously, while soft tissue features like noses don’t fossilise, facial prognathism requires a forward projection of the skull, and skulls generally fossilise well. This allows the hypothesis to be tested by examining facial prognathism in Neanderthal skulls.

When you compare a Neanderthal skull side-on (above left) with that of a human (above right)—you are immediately struck by its distinct facial prognathism—and understand why it is sometimes referred to as the Neanderthal snout.335,336 This forward projection of the midface is actually one of the defining characteristics of Neanderthal morphology—widely used by palaeontologists and archaeologists to identify Neanderthal specimens.

So far, the midfacial projection of Neanderthals has not been explained by any existing scientific theory. But because it is such a ubiquitous and distinctive feature of all Neanderthals, it must have been driven by strong selection forces. Nocturnality and a cold climate appear to explain why a large nose and facial prognathism would be adaptive.

The enormous flat primate nose and the exceptional sense of smell it afforded must surely have been one of the Neanderthals’ most useful weapons, ideal for locating and tracking their prey—including humans. These bloodhound creatures could sniff out their quarry in the dark, hiding in bushes or concealed in tall grass. This kind of sensory acuity allowed them to climb to the very top of the food chain.

Around the world, a few species of modern primates have become nocturnal. All of them have acquired changes to their eyes and visual systems to increase retinal image brightness in low-light conditions.337,338,339 Yale University’s Timothy Goldsmith argues in ‘Optimization, constraint, and history in the evolution of eyes’340 that the evolution of primate colour vision was shaped by an extensive period of early mammalian nocturnal- ity. Based on a comparison of primate visual systems, Callum Ross and Christopher Kirk from the University of Texas at Austin conclude that nocturnal visual predation was a major factor in the early evolution of the primate visual system.341 The eyes of nocturnal primate predators are superbly adapted, allowing hunters to see, chase and capture prey in almost total darkness, aided by exceptional stereoscopic vision that can accurately judge distances in low light.342,343

To achieve these visual feats, nocturnal primates acquired larger pupils and corneas (relative to the focal length of the eye) than diurnal species of similar size. Not surprisingly, Christopher Kirk finds that to accommodate these larger eyes, nocturnal primates have evolved larger optical orbits (eye sockets) compared to species that are active during the day.344

So, if Neanderthals were nocturnal hunters, they would have had larger eyes than early humans.

Can this theory be scientifically tested? Yes, because large eyes need large eye sockets. Just as all nocturnal primate species have extra large eye sockets to accommodate their oversized eyes, Neanderthals’ eye sockets could be expected to be significantly larger than those of humans (below right). And even a cursory review of a Neanderthal cranium (below left) reveals that they are.

It was not just the odd Neanderthal who had these massive eye sockets. Every Neanderthal skull ever discovered has the same extra large eye sockets. To date, there is no explanation for this physiological novelty, which is hardly surprising given that nocturnality has not previously been considered in relation to Neanderthals.

If Neanderthal eyes did adapt to night vision, they would also have to somehow prevent damage to their super sensitive night vision retinas by strong sunlight. In glacial Europe during the Late Pleistocene, Neanderthals’ eyes also had to cope with blinding sunlight reflected off snow. Unless Neanderthals invented sunglasses, their sensitive nocturnal retinas faced the risk of serious damage and even blindness.

Snow blindness would of course affect their hunting prowess so we might expect it to generate selection pressure for some ingenious Darwinian adaptation to get around the problem. One that is common in nocturnal animals is a unique multifocus lens that uses concentric zones of different focal lengths to improve focus in low light. However, as Swedish researchers Tim Malmström and Ronald Kröger from Lund University recently demonstrated, multifocus eyes do not function properly with round pupils. They need slit-shaped pupils, like the crocodile eye (below) to facilitate the use of the full diameter of the lens in low light.345

And as it turns out, one of the added benefits of slit-shaped pupils is that the iris muscles can be closed tighter (like drawing a curtain) so they can shut out more light than round pupils. It’s not surprising then that most nocturnal predators have eyes with slit pupils. For predators, they’re unquestionably the best eyes for the job — so there is a strong possibility that Neanderthals also had slit- shaped pupils.

As to whether the slit-shaped pupils may have been horizontally or vertically aligned, the fact that nocturnal primates like rhesus monkeys, prosimians and owl monkeys all have vertically aligned slit pupils is not a coincidence. It’s because, when one of these animals squints, its horizontal eyelids close at right angles to the vertical slit pupils, blocking out considerably more light than if eyelid and pupil were both aligned horizontally. Given this, it is likely that Neanderthal pupils were also vertically aligned.

Like all nocturnal primates, this woolly lemur from Madagascar (above) has evolved vertically aligned slit pupils to protect its eyes from strong sunlight. © Photo: Matt Scandrett

The theory of Neanderthal nocturnality also appears to explain the evolutionary origins of one of the most distinctive and unique facial features of Neanderthals—their massive double-arched brow ridges. If their hyper-sensitive pupils were prone to damage from strong sunlight and reflected snow, then this would generate selection pressure for prominent overhanging bony ridges above each eye and bushy eye brows to shade the pupils from direct sunlight.

As you can see from these drawings of the skull cap of Neanderthal 1, the bony ridge runs across the forehead just above the eyes, shading the pupils as well as any baseball cap.

Another common nocturnal adaptation that would have affected the appearance of the Neanderthal eye is an optical feature called a tapetum lucidum. If you shine a torch at a cat’s eyes in the dark, you will see its eyes glow ethereally. This effect is created by the tapetum lucidum (from the Latin, ‘bright carpet’), a reflective membrane beneath the retina that re- flects light back to intensify the image entering the eye—ideal for low-light conditions.

Most nocturnal animals have a tapetum lucidum so it is probable that natural selection also bestowed it on Neanderthals. Imagine our Skhul-Qafzeh ancestors sitting around their campfire looking up to see a bunch of Neanderthals rushing out of the darkness, their eyes glowing maniacally with demonic light.

It is worth mentioning here that humans have uniquely clear eye whites or sclera—the pale outer part of the eyeball that surrounds the cornea. Every other primate has brown or reddish scleras, so it is likely that Neanderthals did too.

The Neanderthal nocturnality model makes another important prediction. Nocturnal creatures do not evolve specialised sensory organs in isolation. They need modules in their brains able to process the images, sounds, scents and other sensory data coming from these enhanced organs. In the case of Neanderthals, this would have required the emergence of a larger visual cortex to process low-light visual images.

In primates, the primary visual cortex is located in an area of the brain called the occipital lobe at the back of the skull. In humans, this area is particularly developed to cope with the demands of our heavy reliance on visual imagery. It may be a coincidence, but one of the most pronounced features of Neanderthal cranial morphology is an unusual projection of the occipital lobe, precisely where the visual cortex is located. This bulge is known as the Neanderthal bun, and is conspicuously absent from the modern human skull. Although several theories have been put forward to explain the Neanderthal bun,346,347,348 none has gained wide acceptance.

What we do know, is that the bun extends the Neanderthal brain case, creating a slightly larger brain than modern humans—1500cc compared to 1400cc in humans. It is possible that the Neanderthal bun may have evolved to accommodate an expanded visual cortex, necessitated by a nocturnal lifestyle.

One feature of Neanderthal eyes needs to be noted—their position in the skull. The Neanderthal eyes followed the primate model, and were located much higher in their faces than modern humans, about where our forehead is, giving the impression that the top of their heads had been cut off.

Speech is produced by soft tissues in the vocal tract which do not fossilise, so it’s almost impossible to know exactly what Neanderthals sounded like. Or even whether they possessed a capacity for fully-articulate speech. But that hasn’t stopped scientists and linguists from examining and measuring Neanderthal vocal tract bones and devising complex computer models to make some informed guesses. Although Neanderthals had a hyoid bone (which allows for more tongue movement) most researchers now seem to be of the opinion that the shape and size of the Neanderthal vocal tracts would not permit fully-articulate speech.

In a September 2008 paper presented to the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, researchers from Florida Atlantic University asked, ‘Were Neanderthals tongue-tied?’349 They used several methods to determine that the size and shape of the Neanderthal tongue was quite different from that of humans and concluded, “These results suggest that Neanderthals did not have the ability to produce quantally based spoken language, leading us to conjecture that the answer to the question posed in the title must have been ‘yes’.”

At the same 2008 conference, delegates heard from a team of American scientists who had examined and compared the vocal tracts of Neanderthals with humans and chimpanzees. Their results indicate that the large Neanderthal nose would have affected the precision and clarity of their word formation. It also suggests Neanderthals had deep voices:

A large nasal cavity would have decreased the intelligibility of vowel-like sounds, and the combination of a long face, short neck, unequally-proportioned vocal tract and large nose make it highly unlikely that Neanderthals would have been able to produce quantal speech.350

From this and similar lines of research, we might conclude that vocally and linguistically, Neanderthals sit somewhere between higher apes and humans with voices possessing a deeper timbre than humans and lots of deep guttural sounds—but almost certainly no spoken language like ours.