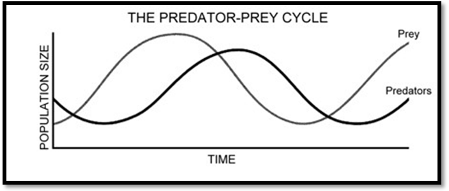

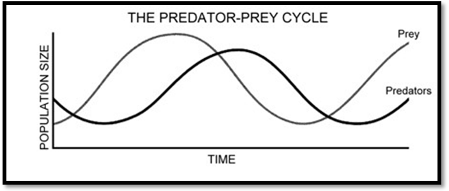

The second prediction of the multidimensional predation model comes from the existing knowledge of predator-prey interactions. If Levantine Neanderthals and humans were locked in an intractable predator-prey interaction, then this dynamic should conform to well-understood aspects of predation ecology—the predator-prey cycle.

The predator-prey cycle describes how predators continue to capture and consume prey, until the prey numbers are reduced to such an extent that they’re no longer worth the time or effort to hunt. This leaves the predator with few options. They can turn to other prey, move to a new territory or starve, in which case their own numbers begin to fall.373 All these scenarios allow the prey population to recover its numbers.374

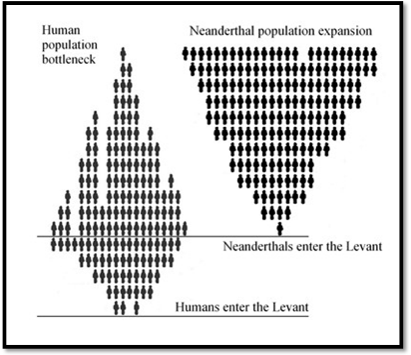

Importantly, while the prey population may be heavily reduced— causing what’s called a population bottleneck, or near-extinction event—it doesn’t normally disappear completely.

If multidimensional predation by Eurasian Neanderthals followed the same predator-prey cycle (and there is no reason to suspect it wouldn’t), then there should have been a gradual reduction in the Skhul-Qafzeh population in the Levant until there were too few humans left to make it worthwhile for Neanderthals to hunt. It’s what ecologists call becoming ‘economically unsustainable’.

The prediction of a population bottleneck is tremendously important in the evolutionary scheme of things. Near-extinction events are one of the few means of generating the kind of powerful selection pressure needed to create a new species. For example, on the Galapagos Islands, two ornithologists researching finches actually witnessed a rare example of the impact of a near-extinction event. During a protracted drought caused by El Nino, 85 percent of the finches on one island died of starvation because the small seeds on which they normally fed failed. The only birds to survive were those with unusually large beaks, able to crack open the bigger seeds that had survived the drought. When the drought ended, all the new hatchlings featured this larger, more robust beak.375

Only a near-extinction event could have generated sufficiently potent and prolonged selection pressure to kick-start and consolidate the speciation event that created modern humans. In effect, a near-extinction event was the door through which our ancestors had to pass. On one side, they were primitive stone-age people. But when they emerged on the other side, they were fully human, smart and articulate—much like us.

MODERN HUMANS AND FULLY MODERN HUMANS

For simplicity, I describe the Levantines who survived the population bottleneck as ‘modern humans’, and reserve the term ‘fully modern humans’ for today’s people. This acknowledges that the post-bottleneck people (although ostensibly Upper Palaeolithic) still had to undergo some last-minute tinkering and fine-tuning before they became fully modern humans.

To determine when the near-extinction event occurred—when our Skhul- Qafzeh ancestors were thrust through the magic portal—we need to consult the archaeological record. It tells us that up to around 55,000 years ago, the Levantine people were still Middle Palaeolithic. It also shows that Upper Palaeolithic culture appeared in the Levant 46,000 to 47,000 years ago, which indicates the bottleneck was at its most extreme around 49,000 years ago. That would leave one or two thousand years to rebuild the population before it again became visible in the archaeological record. By predicting an estimate of approximately 50,000 years ago, NP theory has provided a figure to test.

Whether there were multiple population reductions, as seems likely, or only one major bottleneck is impossible to say. But reliable genetic evidence indicates that one severe population bottleneck began around

70,000 years ago and reached its nadir between 50,000 and 48,000 years ago. In other words, although the two Levantine species may have coexisted in the same region from 100,000 years ago (or even earlier), low population densities, migratory patterns, maintenance of separate territories and evasion meant the near-extinction event did not occur immediately. The Skhul-Qafzeh humans managed to hang on, finding ways to survive in small groups and out-of-the-way places. Eventually, though, the Neanderthals grew too strong, too numerous, or simply too predatory, and slowly but surely the numbers of early humans living in the Levant began to decline.

Because the prediction of a recent human population bottleneck goes to the nub of NP theory, it is important to prove this hypothesis before we proceed. The first proof comes directly from the archaeological record in the Mediterranean Levant, which shows that around 80,000 years ago the population of archaic humans in the Levant is reduced to such an extent that they effectively disappear from the fossil record.376,377 Then, around 50,000 years ago, they reappear.378

The disappearance of human artefacts and bodies from Levantine sites 80,000 years ago may simply mean that all the disparate tribes of humans occupying the Middle East decided to migrate out of the area simultaneously (for whatever reason.) But it is also consistent with the argument that the population, having been drastically reduced by Neanderthal predation, was so small it could no longer be detected in the fossil record. In archaeology, this is called insufficient sampling and it just means that the original population was so small, and fossils so few and far between that there is little likelihood of finding remains. For example, it is salutary to note that the complete history of Neanderthal and human occupation of the Levant—numbering hundreds of Middle Palaeolithic sites,379 and hundreds of thousands of individuals over nearly 300,000 years—is represented by diagnostic skeletal remains from only 11 stratigraphic levels.380

If the Levantine humans had been driven out of their caves by Neanderthals and forced to adopt a nomadic existence below the Neanderthals’ radar, this would also contribute to the group’s invisibility in the Levant archaeology. If their numbers were reduced to a few tribes, and they were constantly on the move to stay one step ahead of the enemy, they would not leave the same archaeological footprint as large populations permanently occupying sites for thousands of years.

Attempting to answer his own question, “What happened to the humans at Skhul and Qafzeh after 80 Kyr?” John Shea notes that, in their place, Neanderthal fossils appear in the same Mt Carmel caves once inhabited by early humans.381 This cluster of limestone caves, rock shelters and overhangs on Israel’s Mt Carmel, and the stone tools found there, testify to a continuous occupation by early humans for thousands of years until, abruptly, they are replaced by the distinctive tools and weapons of Eurasian Neanderthals. The Neanderthals had taken over the caves once inhabited by the Skhul-Qafzeh people.

While Shea concludes Neanderthals may have competitively displaced the Skhul-Qafzeh humans from the Levant, a range of other theories has also been put forward to explain the disappearance of the early humans after such a long occupation, as well as the spread of Eurasian Neanderthals across the Levant. Some researchers believe it was due to the proliferation of Neanderthal populations and settlements in the Levant.382 Others claim that cold adaptation traits may have allowed Levantine Neanderthals to survive better when the climate got colder.383

Another view is that Neanderthals’ increased mobility patterns gave them the edge over humans, allowing them to get around more and locate more prey and better sites.384 And some researchers believe that the two groups became assimilated into a single group through interbreeding.385,386

One scenario that has received scant attention is the possibility of violent replacement. One reason is that the Levantine archaeological record does not reveal clear and unambiguous fossil evidence of warfare (crushed skulls, cut marks on limb bones, etc) between the species.387

This is not surprising. The only place archaeologists have found skeletal remains is at campsites and caves when carcasses have been brought back to consume. Normally, once a predator has killed a prey and eaten its fill, the remains are quickly scavenged by wild animals or birds. Field observations of avian and terrestrial scavengers in Africa suggest that carcass remains (including teeth and bones) are completely eradicated within a day.

It has also been argued that violent melees between present-day hunter-gatherers and large carnivores are dangerous and often lethal, so Neanderthals and humans may have tried to avoid each other whenever possible. But this speculation is based on the assumption of mutual fear, as between two equal adversaries. This wouldn’t apply to an apex predator like the Neanderthal. Predators don’t avoid or fear their prey, they actively stalk them.

The one thing we know for certain is that between 70,000 and 50,000 years ago, at exactly the time it is suggested that Neanderthals controlled the Levant, there were no new African migrations into the region. No one came north to claim the territory once occupied by the Skhul-Qafzeh people. Here was an incredibly fertile stretch of land surrounded on all sides by arid deserts, and yet no group of hominids thought to colonise it. Instead, African migrations exclusively followed an eastern route, along the Indian Ocean coast through the Indian subcontinent and as far as China.388,389

This is exactly what would be expected if the Levant had become a no go zone—due to the belief that dreadful flesh-eating monsters lived there. This would suggest that, even in the low-brow world of Late Pleistocene hominids, the Levant had become known as a place from which very few returned, a land peopled by terrifying creatures. This is a forerunner of the warnings medieval cartographers placed on the margins of their maps to describe dangerous or unexplored territories. Often accompanied by images of sea serpents and other mythological monsters, would be written, “Here be dragons”.

Even though the near-extinction scenario complies with Darwinian the- ory and ecological modelling of predator-prey interactions, it is impos- sible to know exactly what transpired 50,000 years ago to those Levantine humans living precariously on the eastern shoes of the Mediterranean. Fortunately, some recent technological advances in molecular biology have allowed geneticists to date when major evolutionary milestones occurred. This technological marvel hinges on the fact that certain elements in the DNA molecule are known to mutate at a steady predictable rate so, by counting the number of these mutations, geneticists can estimate roughly when major new mutations occurred. For example, the number of these markers in say, a language gene, can be used to calculate approximately when we acquired the capacity for complex spoken language.

In one such study, Pascal Gagneux, from the University of California at San Diego, and a team of European geneticists examined and compared a unique sequence of genetic markers from nine African or African- derived primates—including all gorilla, chimpanzee, bonobo and orangutan species—plus human and Neanderthal DNA. Not unexpectedly, they found considerable genetic variability between the species, but what did come as a surprise was that, of all the species tested, humans had by far the least amount of genetic variation within one species.

Gagneux’s group was nonplussed to find that chimpanzees have four times more genetic diversity than humans:390

We actually found that one single group of 55 chimpanzees in West Africa has twice the genetic variability of all humans. In other words, chimps who live in the same little group on the Ivory Coast are genetically more different from each other than you are from any human anywhere on the planet.391

The implications of this are quite confounding. How can there be more genetic variety in 55 chimps in a remote African rainforest than in six billion humans—scattered across the globe?

It just doesn’t make sense. Normally mutations accumulate in our genes at a slow but fairly predictable rate, and these genetic variations spread as populations move and interbreed. Besides, humans have been around for millions of years and should have accumulated an enormous genetic range by now. Logic suggests that if we split from our primate cousins six million years ago, we should have at least as much genetic variation as they have. But this is not the case. It is only the human branch of the genetic tree that has been drastically pruned.

These results directed the researchers to a single inescapable conclusion—at some point in our evolutionary history, a severe population bottleneck (or near-extinction event) had occurred.392 At some point in our evolutionary history, the human race came within a whisper of becoming extinct.

According to Bernard Wood, Professor of Human Origins at George Washington University, this severe pruning of our family tree was totally unexpected. “The amount of genetic variation that has accumulated in humans is just nowhere near compatible with the age [of our species]. That means you’ve got to come up with a hypothesis for an event that wiped out the vast majority of that variation.”393

The most plausible explanation is that at least once in our past some situation caused the human population to drop to what Wood describes as “within a cigarette paper’s thickness of becoming extinct”.

When unexpected or controversial findings like this crop up in science, there is usually a rush by other scientists to duplicate the experiment or study. If they cannot reach the same conclusions, the original findings are usually discarded or at least revised. But in the case of Gagneux’s findings, they were quickly confirmed by several other studies.394,395,396

But just how low did our ancestral population go? How thin was the line between the six billion humans living today and our tiny band of founders? A meticulous study, headed by a geneticist at the Harvard Medical School David Reich, has come up with an answer. By analysing a non-random mutational process called linkage disequilibrium, Reich and his team calculate the population of humans dropped to as few as 50 individuals.397

What’s more, they calculated the population stayed that low for a long as 20 generations.398 According to their data, our ancestors were hanging precariously onto life by their fingernails—literally on the precipice of extinction—for 400 years.

This doesn’t mean the 50 lonely people were the only archaic humans or hominids left on the planet at the time. There were doubtlessly countless others scattered throughout the vast expanse of Africa and Asia. But what it says is that it was only these 50 individuals that contributed genes to the human genome. I argue the great panoply of humankind is derived from 50 Skhul-Qafzeh individuals. These genetic castaways were to be the sole breeding stock for all of humanity. The others died out without contributing any significant DNA to our gene pool.

Now to the all-important question—when did the population bottleneck occur? Five million years ago? One? Or even 250,000 years ago? Any one of these dates would be enough to sink NP theory. Or did it happen, as the NP model predicts, very recently—a scant 48,000 years ago?

NP theory provides a new timeline for human evolution. It reveals that when archaic humans entered the Levant from Africa, their population gradually increased until Neanderthals moved in from Europe, beginning the period of Neanderthal predation. As the Neanderthal population grew, the archaic human population dwindled until it reached the population bottleneck. At this point there were as few as 50 humans left in the entire Levant.

In 1995, three geneticists—Simon Whitfield, John Sulston, and Peter Goodfellow—answered this question. Writing in Nature, the team re- ported their analysis of mutations in 100,000 nucleotides of the Y chro- mosome (the male sex chromosome) in males from five different ethnic groups. Their findings provided an estimate to the most recent common human ancestor of between 37,000 and 49,000 years ago.399 This fits neatly with the scenario proposed by NP theory for when the bottleneck occurred.

In 2003, another team of geneticists and computational biologists, led by Gabor Marth from Boston College, painstakingly extracted data from

500,000 human mutations (single-nucleotide polymorphisms). Marth and his team calculated the population collapse happened around 1600 generations ago. The researchers estimated each generation at 25 years which means the population bottleneck occurred around 40,000 years ago.400 But if the population was shrinking, then the normal reproductive cycle would be disrupted so the generation cycle would effectively increase. At 30 years per generation, which seems more likely, that yields an estimate of 48,000 years.

Another team, counting mutations in a different part of the DNA molecule (called mitochondrial DNA mismatch distributions) arrived at a figure of 40,000 years ago, or thereabouts.401 And in 2001, David Reich’s Harvard team estimated the bottleneck occurred sometime between 27,000 to 53,000 years ago.402

Allowing for statistical margins of error, my estimate that a near- extinction event occurred around 48,000 years ago is in the same ball park, and consistent with both molecular data and the archaeological record of the disappearance of the Skhul-Qafzeh humans from the Levant between 80,000 and 50,000 years ago.

As well as the archaeological and genetic evidence pointing to an unprecedented population reduction in recent human history, there is another line of evidence to consider. Modern humans all around the world are very similar, despite superficial external differences such as skin and hair colour.

This close similarity also extends to behaviour. Human nature is invariant across cultures. There are minor cultural variations (or national character) but talk to people for a few minutes and you soon realise that from Timbuktu to Tallahassee, Taiwan to Tierra del Fuego, we’re very alike. All humans belong to the same single species. It’s what’s called homogeneity

in biology, and the only explanation for it is that all the members of the species are derived from the same small founding population, just as NP theory suggests.

The second prediction that Neanderthal predation drove our Levantine ancestors to the brink of extinction raises the question: who survived and why?