All the archaeological evidence, the molecular genetic analysis, and the uniformity of modern humans supports the proposition that a near-extinction event took place in recent human history.

But that doesn’t explain what caused it. It exists in the anthropological literature as yet another enigma in human evolution.

However, in NP theory, a near-extinction event that almost exterminated the human race is precisely what is expected and predicted. It is the only ecological situation potent enough to precipitate the speciation event that created modern humans. It follows then that NP theory also predicts that, although it was severely reduced, the Skhul-Qafzeh population survived the bottleneck and recovered its numbers. This too is confirmed by the Levantine archaeology. Humans reappear in the Levant fossil record about 50,000 years ago.403

NP theory proposes that as the population was culled, the few remaining Skhul-Qafzeh survivors from across the Levant banded together into a single population (or tribe) for protection. Although originally from different tribes, these individuals overcame their xenophobia because unity provided an added degree of safety and security. This resilient group became the founding population of the human race.

This narrows the focus of our inquiry onto those hardy individuals who survived the near-extinction event, and raises a number of questions. But science is all about asking the right question and, in this case, that is: why did those few individuals survive when everyone else fell victim to the Neanderthals?

Charles Darwin offers a clue in The Origin of Species: “It is not the strongest of the species that survives,” he writes, “nor the most intelligent. It is the one most adaptable to change.”

The Levantines that survived did so because they changed—they adapted. But how? At the coalface of predation, what physical and behavioural traits were lost because they were maladaptive, and what new adaptive traits took their place? While the big picture answer is obvious— they survived because they acquired adaptations that assuaged the worst effects of predation—this explanation lacks detail. There is a need to understand precisely which existing traits increased their vulnerability (and were lost) and which new ones were acquired because they contributed to their survival and reproductive success.

Field studies confirm that natural selection retains adaptations that help prey species survive, avoid or accommodate predation.404,405 So the third major predicted outcome of Neanderthal predation is that, as Neanderthal predation decimated the population of Levantine Skhul-Qafzeh humans, a range of ‘antiNeanderthal’ defensive and avoidance adaptations were selected and fixed.

These new adaptive traits spread through the whole population—this didn’t take long because the bottleneck population was initially so small. Theoretically, the more Skhul- Qafzeh humans that died as a result of multidimensional predation, the more selective pressure was generated for adaptations to reduce the death toll. It is ironic to think that the more adept Neanderthals became at catching and killing humans and poaching their females, the more the humans acquired adaptive countermeasures.

There were three separate but complementary evolutionary mechanisms that created the anti-predator adaptations and ensured their rapid fixation.

The first and most obvious evolutionary mechanism is natural selection. In the Levant this worked in two ways. The first we can call negative selection—all the Levantine humans who could be caught by Neanderthals were caught and killed. The victims would include all the slow, reckless or not very bright individuals, and their deleterious genes would have been removed from the human gene pool.

But natural selection can also be positive. Positive selection would retain neurological and behavioural mutations that increased hyper- vigilance for Neanderthals and improved early recognition and escape strategies. Physiological adaptations that reduced capture rates, such as increased running speed, agility, hand-eye coordination, athleticism, language, intelligence and forward planning would also come under positive selection. What makes natural selection so powerful is that it is a two-edged sword.

Contrary to the popular view that Neanderthals and early humans coexisted and voluntarily interbred, it makes more sense that if Neanderthals really were formidable, brutish and merciless predacious adversaries, the last thing a Skhul-Qafzeh human would want to do is fraternise with one. When it came to choosing a sexual partner, humans would chose only human mates, with a preference for those who were as dissimilar as possible to the dreaded Neanderthals.

In this way, sexual selection established a small exclusive breeding circle, where the members interbred only with those displaying a specific range of highly-prized physical and behavioural features. At the same time, they would also avoid anyone who looked or behaved like a Neanderthal (including hybrids in their own group) so these genes would be gradually removed from the gene pool.

This suggests that sexual selection and mate choice played an important role in the evolution of modern humans. In acknowledging this, we need to put aside our reticence to consider psychological factors in evolutionary dynamics, and recognise that mate selection is driven primarily by emotional and attitudinal factors. Skhul-Qafzeh humans would have feared and despised Neanderthals and these powerful emotions became set in stone over thousands of generations by the continual trauma of brutality, predation, sexual assault and being devoured. So, there is every reason to believe the emotional attitude of our ancestors towards Neanderthals, and the consequent selection of mates, was an important causal factor in the evolution of modern humans.

Among the higher mammals—and this is particularly true of primates— it is usually the female that is proactive in selecting a mate. While males will mate with any female in oestrus, females are more discriminating. This would suggest that Skhul-Qafzeh females used sexual selection as an evolutionary tool more than the males did. But, as we are about to see, the final mechanism of selecting anti-Neanderthal traits was wielded almost exclusively by males.

When Darwin coined the term natural selection, he meant that nature was doing ‘the selecting’—that the natural environment the organism lived in was a major determinant of which members lived and which died. In addition, Darwin described artificial selection: the way farmers and breeders intentionally select certain traits in domestic animals, which is a relatively benign form of artificial selection. However, the term also applies to the lethal form of selection—almost always applied by human males—as to who lives and who dies.

So the third way that anti-Neanderthal adaptations spread was by artificial selection—where coercion, ostracism, banishment and lethal violence by Skhul-Qafzehs gradually removed from the gene pool any individual who (for whatever reason) they considered too Neanderthaloid. NP theory holds that, throughout the Late Pleistocene, coalitionary groups of human males increasingly resorted to infanticide and homicide to eradicate Neanderthal-human hybrids, excessively hairy individuals, deviant neonates, or anyone who looked like a Neanderthal.

One of the most salient features of artificial selection is its speed. Unlike natural selection, which tends to create gradual change over thousands of generations, even benign forms of artificial selection can occur very quickly. A good example is the selective breeding experiments carried out in the 50s by the Russian geneticist Dmitri Belyaev to produce tame foxes. By selecting only the tamest foxes to breed, Belyaev and his team turned a colony of wild silver foxes into domestic pets within ten generations. The new animals were not only unafraid of humans, they often wagged their tails and licked their human caretakers in shows of affection. Even their physiology changed—the tame foxes had floppy ears, curled tails and spotted coats.

However, this rapid transformation of Belyaev’s foxes pales into insignificance compared to lethal and pernicious forms of human artificial selection—including genocide, ethnic cleansing, racial vilification, religious persecution and pogroms—that can exert a significant evolutionary impact almost overnight. The long history of such affronts and their ubiquitous application by disparate cultures separated by thousands of years supports the hypothesis that aggressive Skhul-Qafzeh males would have no compunction in eradicating anyone they felt was more them than us.

Historically, lethal violence and genocide have not been the business of women. Throughout human history, they have mostly been the preserve of males, and there is no reason to believe it was any different in the Late Pleistocene. Males claimed lethal violence as their own instrument of artificial selection. Groups of men decided what constituted a Neanderthaloid trait, and who felt like a Neanderthal. Men became the ultimate arbiters of who and what was acceptable. It was they who decided who lived and who died.

Given this, the use of artificial (or lethal) selection to remove anti-Neanderthaloid traits would be more prevalent on females, children and infants than on adult males. Sociological and anthropological evidence appears to support this more nuanced view.

Evolutionary biologist Ronald Fisher observes that when a trait conferring a survival advantage also becomes subject to sexual selection, it creates a positive feedback loop that leads to very rapid uptake of the trait. But we can now see that in the Levant it was not only natural selection and sexual selection that were working together to rid the population of hybridised individuals and Neanderthaloid characteristics. The process was also being logarithmically boosted by artificial selection—as coalitions of aggressive males banished or murdered their way towards the same common objective—towards a new kind of human that looked, sounded, smelt and behaved less like a Neanderthal. This blind, inexorable process would have made a substantial contribution to human evolution by identifying and quickly culling vestigial Neanderthal genes from the nascent human genome.

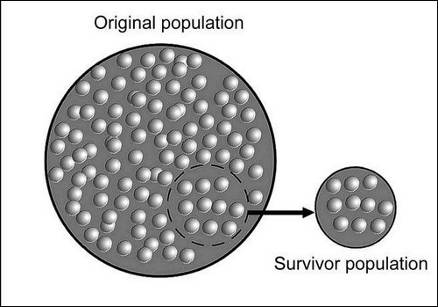

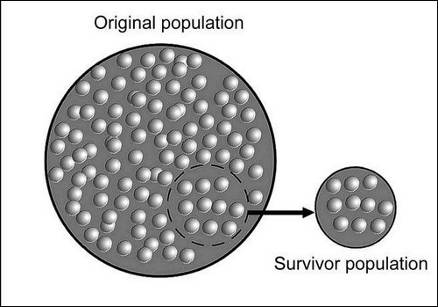

When the original Levantine population of Skhul-Qafzeh early humans was decimated by Neanderthal predation, the survivors became the nucleus of a new founding population of modern humans.

NP theory argues that the three Darwinian mechanisms of evolution (natural selection, sexual selection and artificial selection) focused on acquiring defensive adaptations to reduce the death toll, and to remove every vestige of hybridisation and Neanderthalism from the human line- age, but they were aided and abetted by the fourth Darwinian evolutionary mechanism—genetic drift.

Genetic drift is a dynamic that occurs when some members of a species are physically isolated from the parent population—either because they migrate away, or are separated by some geological feature—like a river or mountain range. When the isolated group begins interbreeding among itself, whatever distinctive physical and behavioural features were present in the breakaway individuals tend to spread throughout the group. This is particularly noticeable when the group is small. As the group expands, these sampling errors show up as a founder effect—for example, everyone ends up with red hair or blue eyes.

The tiny, bottleneck population of Skhul-Qafzeh humans in the Levant provided the ideal conditions for genetic drift to consolidate the changes brought about by the three other Darwinian evolutionary mechanisms. Had the Levantine population been in regular contact with the outside world at the time—if they had been exchanging genes with early humans from north Africa or central Asia—the impact of Neanderthal predation would not have been so acute. As it happened, the sexual isolation of the Levantine Skhul-Qafzeh population was a crucial fortuitous factor in the emergence of sapiens.

So, now we have the four known evolutionary mechanisms (natural se- lection, sexual selection, artificial selection and genetic drift) all exerting blind evolutionary pressure in the same direction. And the closer to ex- tinction the Levantine Skhul-Qafzeh population got, the more potent these four mechanisms became.

This four-pronged evolutionary assault represents an exceptionally rare biological phenomenon. In the extensive literature of evolutionary biology, there is no other documented case of such concerted, multi-faceted evolutionary pressure. The four-pronged evolutionary imperative—what I call meta-selection—is the only evolutionary mechanism sufficiently robust and focused, and possessing the requisite selection momentum, to create a new hominid species, radically different from every other, in such a short time.

Meta-selection is the key to modern human evolution.

The reason meta-selection was so effective was because it not only removed Neanderthaloid and primate traits, but selected a whole raft of distinctively new human traits. It also removed the victims of predation and consolidated new defensive traits in the remaining survivors.

This process of removal and replacement widened the species divide and effectively put human evolution into hyper drive. In the 3.4 billion years of the evolutionary history of life on earth, nothing like this had ever happened before.

The most effective way to thoroughly test these hypotheses is to examine the specific physical and behavioural traits that meta-selection removed, along with the new adaptations that replaced them. For the sake of this analysis, the anti-Neanderthal adaptations are separated into five categories:

• Adaptations to help identify and differentiate Neanderthals

• Adaptations to counteract sexual predation

• Adaptations to avoid being captured or killed

• Social adaptations

• Adaptations to protect against nocturnal predation

Remarkably, these adaptations include all the major features that distinguish humans from other primates. In short, they are what make us human.