When it comes to predation, prey species rarely get a second chance to rectify any lapse of vigilance. Because early detection and identification of predators have such a strong

bearing on survival, selection pressure is generated for prey species to acquire neuronal networks and sensory organs to maintain vigilance for predators.

In addition, over time each prey species builds up an innate description of its predators to help identify them—even those they’ve never seen before. Although little understood by scientists, this instinctive knowledge of a predator’s characteristics is thought to include visual, auditory and other sensory cues that trigger an adaptive response, usually an escape strategy. For example, in 1951 Dutch ethologist Nikolaas Tinbergen devised an ingenious experiment to show that new-born turkey chicks, fresh from their shells, will run for cover when they see a hawk, but will not respond to pigeons, gulls, ducks or herons.406 So, too, birds like the great kiskadee that have never seen a coral snake before, can instantly recognise its distinctive stripes, comprehend that it is dangerous and make their escape.407 Similar experiments with other animals confirm that animals that have never seen their natural predator can recognise and respond to its predatory markings.408

At Sydney’s Taronga Zoo, I watched an Australian black- breasted buzzard pick up a stone in its beak and use it to crack open an emu egg. Young buzzards don’t have to learn this clever trick because it’s hard-wired into their genes. Likewise, I once saw a friend’s toddler respond to a huntsman spider that crawled into his cot by instinctively slamming his fist down on it. His amazed parents assured me he’d never seen a spider before.

As a prey species, there can be little doubt that early hominids acquired a range of similar innate predator identifiers through natural selection. But in the case of Levantine humans and Neanderthals, this would have been more difficult because the two species originally looked somewhat similar. When they first saw each other, they would have been immediately struck by the differences, but they may also have recognised a kindred soul—of sorts. After all, they were both bipedal hominids, roughly the same size and shape and, if they both had primate faces and were covered with hair (even if of a different colour and thickness) then, for these simple- minded folk, identification may well have been problematical. It is safe to assume, therefore, that any feature that accentuated any physical or behavioural difference between the sibling species, and facilitated early and accurate identification, would become an identifier and therefore the subject of meta-selection.

For example, if Neanderthal fur was longer and denser, the eyes larger, and the pupils a different shape, then these features—in humans—would come under the closest scrutiny. This preoccupation with hair and eyes would result in selection pressure in humans to be different—to ‘increase the visual gap’ between the species.

Over time, the demands of predator identification would gradually accentuate the physical differences between the two species. Nobody would want a mate who looked like a Neanderthal, so the new ‘human look’ became increasingly subject to sexual selection. As the ‘new look’ became de rigueur, the old look became subject to artificial selection. Not having ‘the look’ was not only seriously ‘uncool’—it was likely to get you killed.

The characteristics which came under the most intense meta-selectional pressure were physical features that could be seen from a distance, because early identification of a predator is at the core of survival. This would mean that, for humans, body hair (length, density and colour) gait, posture, body silhouette and facial features were the most obvious foci of predator identification and differentiation.

Although it is interesting to speculate on what colour skin the Skhul- Qafzeh people had, it was not a factor at the time because it is almost certain that the Skhul-Qafzeh people were covered in dense body hair.

While readers may find the prospect of recent human ancestors sporting so much body hair unpalatable, this is precisely what NeoDarwinian theory predicts. Coming from Africa where they occupied an open savannah environment, it is highly likely that the Skhul-Qafzeh people acquired a coat of protective hair to insulate them from the hot African sun and its equally cold nights. The same reasoning suggests that—like lions, monkeys and other mammals occupying the same grassland environments—light- brown fur would probably have been most adaptive because it facilitated concealment from predators. So, what happened to the hair? Can NP theory shed any new light on this age-old question?

The loss of body hair in humans—but in no other primate—has generated a vigorous debate among anthropologists for decades. It‘s particularly puzzling in light of the fact that hairlessness is maladaptive in terms of climate extremes, heat stress, sunburn, skin cancers, hypothermia and low ambient temperature environments.409,410

HUMAN HAIRLESSNESS

Actually, modern humans are not hairless. But discarding our thick, long and highly pigmented hair, (called terminal hair) in favour of fine, short and unpigmented vellus hair has created the impression of hairlessness.411 For the purposes of this book, terms like hairlessness and denudation are used even though they’re not strictly correct.

In Before the Dawn, Nicholas Wade outlines the paradox:

Hairiness is the default state of all mammals, and the handful of species that have lost their hair have done so for a variety of compelling reasons, such as living in water, as do hippopotamuses, whales and walruses, or residing in hot underground tunnels, as does the naked mole rat.412

Innumerable theorists have attempted to explain why only humans turned into a ‘naked ape’, including Charles Darwin who argues:

No one supposes that the nakedness of the skin is any direct advantage to man; his body therefore cannot have been divested of hair through natural selection.[…]in all parts of the world women are less hairy than men. Therefore we may reasonably suspect that this character has been gained through sexual selection.413

A variation of Darwin’s sexual selection theory has been proposed by American psychologist Judith Rich Harris. She believes that hairlessness and pale skin are the result of sexual selection for beauty, which operates through a form of infanticide she calls parental selection.414 Harris argues that historically, parents frequently killed infants they didn’t consider beautiful enough, and one of the criteria for beauty she nominates is hairlessness.

Another group of scholars contends that hairlessness emerged six to eight million years ago in hominids who lived an aquatic or semi- aquatic existence for between one and two million years.415,416 This is the controversial aquatic ape theory which, despite arousing some initial interest, has not stood up well to critical evaluation and has been largely discredited.417

Yet another group of anthropologists claims hairlessness was selected because it helped in detecting and removing ectoparasites likely to harbour diseases.418 But why other primates did not lose their hair for the same reason is not explained. Nor does the theory address the retention of warm, moist pubic hair, which is a veritable haven for body lice.

But probably the most popular theory remains thermoregulation. Its advocates argue that hairlessness helped to cool bipedal hominid hunters when they migrated from the African rainforests to the savannah and began hunting large animals.419 Anthropology professor Albert Johnson Jr suggests:

Specifically, any diurnal hunter on the African high veldt would have needed a mechanism to dissipate excess heat which would almost have certainly been generated due to moving about under the equatorial African sun. Therefore, selection would have operated to reduce the amount of body hair on these hominids largely because heat dissipation would not have been possible if they had remained covered with hair.420

This makes sense in theory, but not in practice. Medullated terminal hair is actually an excellent insulator against both heat and cold, and creates a consistent ‘microclimate’ that is adaptive in a wide variety of climatic con- ditions.421 Losing this hair would in fact subject humans to both increased heat and cold stress.

Writing in the Journal of Human Evolution, Lia Queiroz do Amaral reported that, at high temperatures, thermal stress is up to three times greater on a naked human than on a primate covered with terminal hair.422

This is why, according to another study, the fur of savannah primates is actually denser than that of forest-dwelling primates.423 Chimpanzees, bonobos, baboons, and gorillas—all from the hottest equatorial regions of Africa—have retained their thick body hair.

Also challenging the thermoregulation theory is the sunburn factor. Hair protects animal skin from sunburn and melanomas. And, if hairlessness doesn’t make sense as an adaptation to heat, it makes even less sense when temperatures on the African plains can drop to minus zero just before dawn.

The thermoregulation theory claims that hairlessness evolved to cool hunters as they chased prey on the African savannah. However, cross- cultural studies of human hunter-gatherer societies show that hunting large animals is exclusively the preserve of men.424 If only men hunt, why did women also lose their hair?

Lastly, neither the thermoregulation theory, nor any of the other theories adequately address the gender difference in hairlessness (females are less hairy than men) nor the continual preoccupation with hairlessness in modern humans. These gaps, and the lack of a consensus about the evolutionary origins of human denudation, justify re-examining the problem using the NP model.

NP theory proposes that hair loss was driven by the needs of a prey species to quickly and accurately identify its principal predator.

It was not simply a matter of distinguishing Neanderthals from Skhul-Qafzehs. Identification per se has no survival value—unless it occurs early enough to prevent capture. So if extra thick and long body fur was an eye-catching feature of Eurasian Neanderthals, it would allow the less hairy Skhul-Qafzeh people to identify Neanderthals from far away, giving them time to escape.

This would be enough to establish long body fur as a reliable visual demarcation between the species—especially from a distance—which in turn would create a negative association towards hairiness in humans. Fairly soon, this would translate into a sexual preference for less hairy partners, and hairy humans would increasingly be seen as ‘Neanderthaloid’.

In other words, just as female peacocks choose males with the biggest fan-like display of colourful feathers, so too Skhul-Qafzeh humans grew to prefer mates who were less hairy.

This would place all the hairy humans—the outcasts and the wallflowers—not only on the proverbial shelf, but also in danger of being socially ostracised and even murdered: artificial selection. The net effect of this meta-selection ensured that the genes coding for body hair in humans were gradually removed from the gene pool.

It may seem strange that humans could develop such a powerful aversion to something as natural as body hair. But when this aversion is placed in its correct evolutionary perspective, it’s hardly surprising it remains so strong today, 28,000 years after the last Neanderthal has disappeared. Negative attitudes to hirsutism and a preference for hairlessness (personally and in prospective mates) are universal across human cultures throughout recorded time.

Because artificial selection was practised almost exclusively by males, the selection pressure for female denudation would have been even more acute, resulting in women becoming even less hairy than men. This indicates that the pressure on women and girls to be hairless is anchored in the threat of lethal force wielded exclusively by men since the Late Pleistocene. While hairy aggressive men were quite prepared to kill hairy women, they were less enthusiastic about topping themselves.

This reasoning is supported by considerable sociological research which shows modern women and girls traditionally come under greater pressure to be less hairy than men.425,426 For example, a study of 678 UK women in 2005 found that 99.71 percent of participants reported removing body hair.427 Citing examples of depilation in ancient cultures (Egypt, Greece and Rome) and in a variety of modern societies (Uganda, South American and Turkey), cultural anthropologist Wendy Cooper contends that the need for women to remove body hair is deeply embedded in human nature.428

The Neanderthal predation hair loss theory predicts several outcomes that can be empirically tested. Firstly, it argues that hair loss did not oc- cur gradually over millions of years in Africa. It happened in the Levant and coincides with the first contact with Eurasian Neanderthals around 110,000 to 100,000 years ago.

Because body hair protected our ancestors against both heat and cold, allowing them to maintain thermoregulatory homeostasis in extreme climatic environments, its loss was potentially deleterious. Being hairless was particularly dangerous for newborn babies and infants because of the risk of hyperthermia and hypothermia. Newborns are especially susceptible to cold stress due to their thin skin, intensive vascularisation, and the high surface area of skin to body mass.429,430 Even in adults, being stripped of body hair would raise the risk of brain anoxia and acidosis.

This tells us that hairlessness must have occurred concurrently with the evolution of clothing to maintain homeothermy, which in turn provides an excellent means of testing the theory.

Trying to determine exactly when humans started wearing clothes is difficult because skins and fabrics are not generally preserved in archaeological sites. Fortunately, in 2003 a German team of geneticists noticed that the human head louse (Pediculus humanus capitis) feeds and lives on the scalp, while the body louse (Pediculus humanus corporis) feeds on body skin, but lives in our clothing. They reasoned these two species of ectoparasites were originally one species and diverged only when humans began wearing clothes. By dating mutations in their DNA, the scientists were able to date the emergence of body lice and, by inference, the human use of clothing.431 They estimated humans started to wear clothing around 107,000 years ago.432

This agrees with my proposition that denudation and the development of clothing began with the onset of Neanderthal predation in the Levant about 110,000 to 100,000 years ago. However, this is not to suggest that the Middle Palaeolithic Skhul-Qafzeh people had the wherewithal to make needles and sew tailored garments. The first stitched clothes are thought to have been made by using pointed stone awls (which have been found at Levantine sites) to pierce holes in animal skins, which were then sewn together with fibre or leather throngs. Importantly, the gradual loss of body hair by the Skhul-Qafzeh people generated increasing selection pressure for the cognitive modules required to make tailored garments.

Modern humans have a distinctive, straight-back gait unlike any other primate, and this has sparked considerable discussion about its evolutionary origins. Although paleoskeletal evidence indicates archaic hominids were walking bipedally over 3 million years ago,433 anatomically modern human anatomy is much more recent. At some stage in their evolutionary history, humans abandoned their ancestral primate swagger and adopted the flowing stride of today. But what caused the change? And when did it happen?

If the way we walk today is the result of modern human skeletal anatomy, the focus of the search can be narrowed to after humans became anatomically modern. The Kibish hominids from southern Ethiopia, reliably dated at 195,000 years old (5000 years), are probably the earliest humans discovered with a relatively modern skeleton.434 So theoretically, the mechanical-skeletal components of the modern stride were in place sometime in the last 200,000 years. This puts the emergence of the modern human gait within the range of Neanderthal predation, so it is appropriate to ask: could it be yet another legacy of Neanderthal predation?

An animal’s gait is such a distinctive feature and so easily recognised, even over long distances, it provides prey with a quick and convenient method of identifying predators. If chimpanzees, gorillas and humans have each acquired their own species-specific gait, it seems logical that Neanderthals did too. In that case, their distinctive gait would provide early Levantine humans with a conspicuous means of recognising their dreaded foe even at a distance of several hundred metres.

This would generate selection pressure on humans, firstly to abandon aspects of their own gait that were similar to that of Neanderthals, and secondly to develop a new distinctive gait. Very quickly, this could lead to the preferential selection of mates who displayed the new gait. A sexy walk soon became the latest must have feature on the Palaeolithic dating scene. Eventually meta-selection for the new stride wiped out the old ape- like gait altogether.

This hypothesis is based on the assumption that Neanderthals originally had a different gait from the Skhul-Qafzeh humans, and this assumption needs to be tested. While we can observe other primates and speculate from that how Neanderthals walked, a better way is to examine fossilised Neanderthal pelvic, hip and spinal bones to see if they offer any insight into the Neanderthal gait.

When Erik Trinkaus undertook his meticulous re-examination of nine Neanderthal skeletons from Shanidar cave in the Zagros Mountains of Iraq, he found the unique configuration of their pelvis bones, gluteal muscles and lumbar robusticity was quite different from that of early humans and that this would have caused Neanderthals to have a distinctive gait. He also worked out that the curved long bones of their legs would have given them a decidedly bow-legged look.435

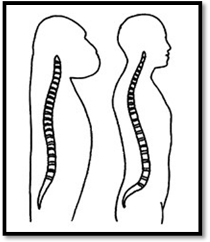

Despite the popular belief that Neanderthals and humans were anatomically identical, the physical difference between the species is evident in the shape of their rib cages. The Neanderthal rib cage (top) is pear-shaped, like that of the gorilla (centre) while the human rib cage (below) is more tubular. This gave the Neanderthals a distinctive visual appearance that humans could use to quickly identify them, even over great distances.

Ian Tattersall, another authority on Neanderthal physiology, observes that the barrel-shaped rib cage, flared pelvis and articulation of the last lumbar vertebra with the sacrum deep in the pelvic bowl (which has the effect of shortening the waist) were all distinctive Neanderthal physical features that “would have assured that the two hominids would have presented very different appearances on the landscape”.436

Tattersall goes on to make the point that the shortness of the Neanderthal waist would have restricted upper body rotation and stiffened the Neanderthal gait, rendering their movement very different from those of modern humans—more ape-like.

These lines of anatomical evidence square with the one universal modern human attitude to gait. Humans everywhere consider a slouched ape-like walk, typified by hunched shoulders, rigid torso, bow-legged, forward lean and loosely swinging arms as physically unattractive.

From the perspective of NP theory, it is not a coincidence that the characteristic modern human stride is universal. Unlike body hair, which varies slightly around the world and between the sexes, there is only one modern human walk. There are no cultural variations, no bow-legged, hunched-over exceptions. The evidence suggests this is the result of concerted and prolonged meta-selection pressure for a single uniform human gait.

Many physical anthropologists—and a good many doctors—have long wondered why the human spine has a pronounced S-shaped curve when every other primate has a much straighter spine. This distinctive characteristic (lumbar lordosis) is perplexing because it seems badly de- signed and injury prone. From an engineering perspective, the spine is a tension-compression structure and the more vertically the lumbar vertebrae are aligned, the more efficient they are at transfer- ring stress, resulting in less injuries. In the human spine, lordosis is produced by a combination of the angle of the sacrum and the wedge shape of the lowest vertebra. Ninety-nine percent of lumbar prolapses occur in these lower vertebrae. Among urbanised, industrialised peoples, the chances of having lower back pain ranges between 50 to 80 percent.437

Natural selection would result in a curved spine only if it somehow increased reproductive success. There must have been some significant advantage, to compensate for the injuries and immobility of the new weaker spine. Could the S-shaped spine be the result of preferential selection during the Late Pleistocene because it helped differentiate the two warring species?

This would mean the human spine acquired a degree of lordosis because, in conjunction with rounded buttocks, it would present a very different appearance from side-on (than Neanderthals) and therefore would be an advantage in the critical issue of identification. Further, this would translate into a curved spine being considered desirable—read sexy—especially when accentuated by rounded buttocks.

This aspect of the theory finds support from sociologist Christopher Badcock, who—in the interests of science—pored through countless men’s magazines to study what kinds of bodies and poses men preferred. On the basis of how many poses featured the accentuated curve of the spine, he suggests that modern human males find this look particularly appealing.438

The spine of the other great apes is much straighter than humans and less prone to injury. Illustration courtesy of the Australian Museum

The lordosis theory is only plausible if Neanderthals had the same straight spine as modern primates. Because the literature on this is scarce, I consulted Erik Trinkaus, an authority on Neanderthal physiology, who said the question of Neanderthal spinal curvature still hasn’t been resolved (personal correspondence). This is partly because Neanderthal vertebrae, when excavated, are nearly always broken or distorted. Often this is exacerbated by the body having been bent to fit a burial pit but, in addition, the weight and movement of the ground is enough to scatter and squash the vertebra. Thus, it is practically impossible to determine the amount of lordosis in the Neanderthal spine.

Devendra Singh, Professor of Psychology at Texas University, has carried out some interesting research into universal male preferences for certain female body types or shapes. He found one striking preference that men from over 18 different cultures consistently share. They prefer women with a waist-to-hip ratio of between .67–.80.439 Women whose waists are on an average seven-tenths as wide as their hips (that’s a ratio of 1:0.7) — regardless of the woman’s overall body size and weight—have been considered ideal by men across time and culture.440

A team of English psychologists led by Martin J Tovée, from the University of Newcastle, reaches similar conclusions.441 Comparing 300 super- models (including Claudia Schiffer, Naomi Campbell and the Wonderbra model Sophie Anderton), 300 ‘glamour models’ from Playboy magazine,

300 average women, plus smaller samples of anorexics and bulimics, they find that, even though the supermodels are taller and thinner, they nevertheless still have .68 hip-to-waist ratios. Glamour models averaged .71.

Evolutionary psychologists have not been able to explain men’s attraction for this particular body shape, so there is no harm in proposing that its evolutionary origins may lie in Neanderthal predation. Judging by preserved Neanderthal rib cages, their torsos (viewed from the front) were straight or even slightly rounded, suggesting that humans may have preferred the hourglass figure because it helped tell friend from foe. The important thing about figure shape is that, even from a distance, the distinct curvy silhouette is very easy to recognise as human. Because this body shape was like a stamp of approval—a guarantee that a female wasn’t a hybrid, or worse still a Neanderthal—men would have found this curvy shape more desirable.

Perhaps because the expressive powers of the face are thought to provide a window into the soul, among modern humans the face is the most important indicator of who we are. It is our most admired, studied, deco- rated, depicted, altered and mutilated feature. Research into the field of subliminal perception reveals that we are constantly on the alert for angry and threatening faces. We subliminally register threatening faces even in a crowd, well before we are consciously aware of them. As a species, we are habitual face readers, shaped by nature to be hyper-aware of subtle facial characteristics.

We see faces everywhere, as if our minds are determined to detect all the faces hidden around us—behind every tree, concealed in every bush. We are particularly aware of facial deformities and simian features.

Such an important function would ensure the human face became subject to meta-selection. This would redesign the conspicuous soft tissue features to create as much visual distance between humans and the Neanderthals’ primate appearance, resulting in the selection of morphological novelties like protruding noses, unwrinkled skin, tumescent lips, facial flatness, clear eye whites, pale skin, reduced brow ridges, a pronounced chin, and facial symmetry. If faces occupy such a privileged position in human consciousness, if we have an abiding interest in what our lovers, children, friends and especially strangers look like, if we are subliminally attuned to threatening faces in our midst, it follows that this innate fascination also extended to Neanderthal faces. What their faces looked like was important to our ancestors and the reason, according to NP theory, is that at close quarters the face provided the most reliable means of differentiating Neanderthals and hybrids from humans.

Today, lethal (artificial) selection is applied less frequently against people with ‘non-standard’ facial features, although in some cultures infanticide still occurs with deformed and exceptionally ‘ugly’ infants. However, sexual selection against Neanderthal-primate facial features in favour of human facial features remains strongly normative in every human culture.

Let’s take one example—facial symmetry. Today studies show that, even though people are usually not aware of it, they universally prefer partners with symmetrical faces.442 This suggests this innate preference may have been acquired because Neanderthal faces were asymmetrical, just as modern chimpanzee faces are.443 In fact, humans have an extraordinary ability to subliminally detect even the slightest facial asymmetry and to associate it with unattractiveness.

Similarly, because we know from examination of Neanderthal mandibles that they didn’t have a chin, humans would acquire an innate dislike of weak chins and a sexual preference for a pronounced chin. This may explain why today the human chin is unique among mammals.444

This hypothesis offers a simple explanation for why the human face is one of the most important visual factors in selecting a sexual partner in modern humans.445 And why it has so many features that are unique to humans. It also adds weight to evolutionary biologist Tomomichi Kobayashi’s proposal that the preference for the “handsome type face in humans” was acquired relatively recently, as a result of sexual isolation during or after the emergence of modern humans.446 This is because all the indicators of human beauty and desirability which people universally use to choose a partner, bear no resemblance to primate features. They are unique to modern humans so, consistent with NP theory, must have emerged as part of the Upper Palaeolithic revolution.

Philosophers and scientists have pondered the aesthetics of human beauty for thousands of years but are still no closer to explaining them, or why our faces look so different from those of every other primate. Finally, we have a simple answer—the human face evolved to be visually different from Neanderthals—allowing us to tell friend from fiend. Today, Neanderthal facial characteristics (as depicted in the forensic reconstruction, left) provide an innate standard by which humans judge ugliness and beauty. The less like this Neanderthal you look, the more ‘beautiful’ you are.