When all the strategic adaptations described in the last chapter are added to the defensive adaptations humans acquired earlier, the result is something that looks very much like a fully modern human. This is not a coincidence. As disagreeable as it may be, this combination of aggressive, murderous, devious, cruel, sexually repressive, devilishly clever and patriarchal characteristics is a substantial part of what define us as a species. These characteristics distinguish modern humans from their stone-age ancestors and from every other primate. Thousands of timid archaic humans went into the population bottleneck, and only a handful of ferocious, militaristic modern humans came out.

Transforming into the most virulent species on earth is what it took for humans to throw off 50,000 years of persecution. Only a superior predator could have reversed the predator-prey dynamic. And only by transforming into something more lethal and dangerous than Neanderthals themselves, could those early humans stake their claim to the top rung of the food chain.

From an evolutionary point of view, the struggle to reverse the predator-prey dynamic (despite being fuelled by genocidal rage) wasn’t personal. It was simply a rudimentary and spontaneous expression of ‘survival of the fittest’.

The Levantine reversal set the tumultuous course of human evolution for the next 50,000 years, honing the strategic adaptations that transformed the Skhul-Qafzeh humans from timid to triumphant, from fearful to fearless. It was here that the die was cast, from which all future humans would be forged. The Levantine humans had become something without precedent in the animal kingdom. For the Eurasian Neanderthals, this new breed of humans must have seemed like Frankenstein monsters, so different were they from their timorous predecessors. To comprehend the sinister nature of the human transformation, I am reminded of something the father of the atomic bomb J Robert Oppenheimer said when he witnessed the first nuclear denotation. He quoted a line from the Hindu scripture the Bhagavad-Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”.

With its red and gold tail plumage, the phoenix is a beautiful bird from Phoenician mythology that was said to live for 500 years. When it is about to die, it builds a nest of cinnamon twigs, nestles in, and sets fire to itself. When the firebird is completely consumed, a new phoenix rises magically from the ashes.

This mythic tale of resurrection and regeneration provides a fitting analogy for what happened to the Skhul-Qafzeh humans. The catharsis of Neanderthal predation decimated their numbers, devastated their lives, and drove them to the precipice of extinction. But just as they were about to disappear forever, enough strategic adaptations took hold to fan the embers and allow a few resolute souls to emerge—belligerent, deadly and looking for revenge.

This scenario of resurrection and retribution encapsulates two major tenets of the strategic adaptation hypothesis and, coincidently, provides two predictions that can be used to test the theory. The first is that strategic adaptations fixed during the population bottleneck transformed Skhul- Qafzeh humans into recognisably modern humans with a new Upper Palaeolithic culture. Secondly, this allowed the post-bottleneck humans to reverse the ancestral predator-prey relationship and go on a genocidal rampage of retribution against their ancestral foe.

If the first prediction is correct, the fossil record of the Levant should show that Upper Palaeolithic culture suddenly appeared there between 50,000 to 46,000 years ago. And it does. The Upper Palaeolithic transition first shows up in the fossil record about 47,000 years ago,562,563,564,565 which is when NP theory proposes that modern humans were emerging from the population bottleneck. Secondly, a plethora of solid archaeological evidence confirms the Levant is the site of the earliest systemic transition from Middle Palaeolithic to Initial Upper Palaeolithic anywhere in the world.566,567,568

Most of the recognised indicators of modern behaviour are there—including prismatic blade technology, the transport of raw materials over long distances, complex multi-component tools (including, for the first time, bone and ivory tools), personal ornaments, specialised subsistence strategies, language capacity, symbolic notation systems, and so on.

The hypothesis argues that the gradual accumulation of new strategic adaptations created a tipping point that resulted in a new species.

One of the methods that biologists use to determine if two populations are the same species is to check whether they interbreed. Even if they look very similar, if they don’t interbreed it’s a sure sign they’re different species. For example, Cope’s Gray Treefrog (Hyla chrysoscelis) and the Gray Treefrog (Hyla versicolor) are visually indistinguishable. The only distinctive thing that separates them is their singing voices, but this is enough to prevent them interbreeding and so they’re classified as separate species.569

So because the Levantine humans that emerged from the bottleneck were no longer subject to sexual predation and interbreeding with Eurasian Neanderthals, they were now a sexually isolated breeding population. If Neanderthal males came around looking for females, they would now be given short shift. The days of predation were over.

More to the point, though, the post-bottleneck Levantines were physically and behaviourally so different from their pre-bottleneck ancestors as to be virtually unrecognisable. This indicates that a speciation event took place. They were no longer Skhul-Qafzeh. Indeed they would probably look down on Skhul-Qafzeh folk as dumb, timid brutes with whom the prospect of interbreeding would be repulsive. In every respect, the post-bottleneck people were now effectively a new species. But what species?

Although they possessed many characteristics of fully modern humans of today, when it came to outward appearances the post-bottleneck modern humans were most likely quite different from both their pre-bottle- neck ancestors and fully modern humans. For a start, they had slightly larger brains (1600cc compared to 1400cc for today’s humans)570 and as a predator species, acquired a more robust skeletal-muscular physiology,571 so they looked bigger and beefier than fully modern humans. And, ac- cording to anthropologist Vincenzo Formicola’s analysis of the data, the males were considerably taller (at 176.2 cm) than their predecessors.572 In other words, this was a transitional morphology—not quite Skhul-Qafzeh, but not quite fully modern human.

Were a crowd of these post-bottleneck humans to appear on the high street today, we might be surprised by how visually different they were from us. Overall these post-bottleneck humans would convey a disconcerting impression. We would probably consider them brutish, ill-formed, hairy and uncouth. And, because their faces appear unbalanced (asymmetrical), we would probably judge them unattractive (even ugly) by modern standards. They are after all, still stone-age cavemen and women.

But it would be their behaviour more than anything else that would make them conspicuous. Over thousands of years of continual interspecies warfare, natural selection had retained the toughest, most aggressive, resilient, merciless individuals. Clearly the selection for aggression and risk-taking was directed primarily at adolescent and young adult males who were the ones doing most of the fighting. One simple mechanism of selection focused on males with abnormally high levels of hormones such as testosterone, which has been shown to increase verbal and physical aggression in young males.573

By a simple application of Darwinian theory, an hypothesis emerges which proposes that the continual selection for aggression in young males (because it was so adaptive) would gradually produce a cohort that was so innately aggressive and predisposed to violence that a new word was needed to describe them. Modern terms like hooligans, ruffians and even barbarians won’t do. Modern descriptions of male group violence are inadequate for these post-bottleneck people, who existed before rules, civilisation, or even humanity as we know it. Their exceptional level of aggression was selected for because it was adaptive. It wouldn’t be today. Only in the context of a war of unimaginable barbarity against a ferocious enemy would this level of aggression be necessary or warranted.

To distinguish this unprecedented level of male aggression, I use the term hyper-aggressive. It describes a repertoire of extreme behavioural responses that emerged in response to the aberrant environmental circumstances prevailing at the time. Male hyper-aggression includes a suite of teemic traits that, in addition to negligible impulse control and aggression, also includes paranoia, callousness, ruthlessness, sadism and absence of empathy, remorse and love.

In 1941, Hervey Cleckley, a psychiatrist with the Medical College of Georgia, described a similar list of personality traits and behaviours in modern humans and called it ‘psychopathology’.574 There can be little doubt that your average post-bottleneck male would be classified as a psychopath according to diagnostic criteria developed by Robert Hare from the University of British Columbia, the current world authority on the subject.

However, it’s important to put the psychopathology of these early modern humans into context. They lived in a time before morals and ethics existed, so of course it follows that they were immoral and unethical. Romantic love was still in its infancy. Empathy for anyone beyond the family or the tribal group was practically anathema. And having a conscience, feeling guilty or empathising with one’s victim was not only useless, it was almost certainly maladaptive.

This NP theory view of a malignantly aggressive ‘psychopathic’ transitional species is at odds with most palaeontologists who argue these people were fully modern—indistinguishable from you and me. Anthropology does not currently recognise the need for an interim species between Upper Palaeolithic stone-age people and ourselves. But NP theory argues that, although the new hyper-aggressive humans had come a long way, their journey was far from over. Natural selection still had a great deal of fine tuning to do (including exorcising the genes for hyper-aggression) before one of these post-bottleneck humans could attend the theatre without causing a riot.

To distinguish the transitional clade of hyper-aggressive early modern humans that sprang from the Levantine bottleneck—cantankerous and spoiling for a fight—I have revived the term Cro-Magnon.

In drama, good characters drive the plot. So, with the dramatic entrance of a compelling new protagonist onto centre stage, our Shakespearian drama of human origins is set for an exciting plot twist, one which will drive the drama to its cathartic climax.

From what we now know about Cro-Magnons, we can predict what happened next. Unconstrained by laws, religion, morals, treaties or codes of civility, hyper-aggressive Cro-Magnons would have embarked on a protracted campaign of retributive violence against the Eurasian Neanderthals.

CRO-MAGNONS

Cro-Magnon was the name given to the earliest modern humans to enter Europe by the French palaeontologist Louis Lartet. Lartet discovered the first five skeletons in the Cro-Magnon rock shelter at Les Eyzies, in south-western France in 1868. Cro-Magnons are the quintessential ‘cavemen’ of popular literature. Although today the term has mostly been supplanted by anatomically modern or early modern humans, I find the term useful to describe a transitional population between Initial Upper Palaeolithic (or modern) humans and fully modern humans.

The object of this ‘proto-war’ was not dietary predation or territorial encroachment, but something quite unique among the anthropoids—killing members of a sibling species out of extreme antipathy. This in turn is based on an innate sense that it was them or us—an instinctive aware- ness that the two species were mutually exclusive—that there is room for only one of them. Armed with their innovative projectile weapons, newly acquired military tactics, courage, cunning and aggression, Cro- Magnons took every opportunity to exterminate every Neanderthal they came across.

This, I believe, was the first time humans killed other than for the purposes of food, the first time they hunted for sport.

From the perspective of a virile young Cro-Magnon male, it is hard to imagine there would be any consideration of the social, political and evolutionary consequences of their murderous campaign. It was intuitive and instinctive—because it was already innate.

Just as lion cubs and other juvenile predators use play to practise the hunting and killing techniques they will use as adults, Cro-Magnon boys would have incorporated their new aggressive proclivities into their development. From an early age, they would have played with toy spears and clubs—the new tools of the trade—and practised hunting and killing Neanderthals. By the time they reached their teenage years, Cro-Magnon boys would be physically, hormonally and socially prepared to take on their fathers’ lethal quest.

Today, boys around the world do not pretend to hunt antelope or mammoths to practise future skills. They play variations of ‘Cowboys and Indians’—seminal them and us battles between humans. These games are the vestigial remnants of ancestral imperatives—innate proclivities that had served to hone the violent duties of adulthood.

There is reason to believe that hyper-aggression included a sexual component. I proposed earlier that one method of achieving hyper-aggression in young Cro-Magnons males was by selecting for extremely elevated levels of serum testosterone. Testosterone also happens to be the primary male sex hormone, elevated levels of which predisposes increased sexual arousal and activity. This means that, not only were Cro-Magnon men hyper-aggressive compared to modern humans, they were almost certainly hyper-sexual as well.

If Cro-Magnon social groups resembled modern hunter-gatherer groups, they would ostensibly congregate in tribes close to fresh water and good hunting grounds. From there, the young men would launch hunt- ing and gathering expeditions, sometimes lasting weeks, or even months. These bands of heavily-armed hyper-aggressive, hyper-sexual young men—genetically charged with a bevy of powerful hormones—posed a threat not only to Neanderthals but to other human populations.

As a hunting and fighting group, the Cro-Magnon men depended on each other for their survival. They hunted, fought, suffered and died together. And doubtlessly they celebrated their victories together. These emotionally shared experiences would create an indelible bond between the men, far more intense than today’s male bonding of football teams and fishing buddies. For Cro-Magnons, male bonding was not just social, it was a life and death issue. As such, it was a functional adaptation that directly contributed to their survival and reproductive success.

Also deeply ingrained in the Cro-Magnon psyche was the concept of them and us. For them, it represented more than a species divide. It was a life and death distinction, adaptive because it was plain and simple enough for them to understand at a visceral, intuitive level. It had almost nothing to do with rational thought and objective reasoning and everything to do with gut instinct—innate prejudices, sex and violence and deeply entrenched them and us mindsets.

There was no precise intellectual concept of them. The description applied to almost anyone and anything outside the group. Any mix of sex and violence could be meted out without the slightest remorse to anyone branded ‘them’. The Cro-Magnons were probably the most psychopathic humans who ever lived—but they were creatures of their time. With a job to do. And if they had not done their job, none of us would be here.

After the population bottleneck, the human population expanded and the Eurasian Neanderthal population plummeted towards extinction.

From a broader sociological perspective, it is immediately apparent what these nomadic bands of hyper-aggressive, hyper-sexed Cro-Magnons were doing. They were practising genocide. It was undirected, haphazard and certainly inefficient by today’s standards, but it was highly motivated. And over a few thousand years, the Cro-Magnons drove the Eurasian Neanderthals to extinction.

The genocide hypothesis fits with sociological studies of lethal aggression by male coalitions (modern armies) and with a long history of human warfare, xenophobia and genocide.575, 576, 577, 578

In The Descent of Man, Charles Darwin has this to say on the propensity of humans to kill off those they considered inferior:

All that we know about savages, or may infer from their traditions and from old monuments, the history of which is quite forgotten by the present inhabitants, shew that from the remotest times successful tribes have supplanted other tribes.579

More importantly, the theory that humans annihilated the Eurasian Neanderthals is consistent with the fossil record of the Levant that shows the Neanderthals disappeared just after the first appearance of the first Upper Palaeolithic humans in the Levant.580,581,582,583

John Shea says:

Throughout Western Eurasia, the end of the Middle Palaeolithic period marks the last appearance of Neanderthals in the fossil record. Between 30–47 Kya, Upper Palaeolithic humans expanded their geographic range to include all the territory formerly occupied by the Neanderthals and other anatomically archaic humans. The Middle Palaeolithic period in the Levant was the last period in which modern humans had serious evolutionary rivals for global supremacy.584

NP theory goes even further, predicting that a genocidal war took place, that it was successful, and that it was relatively quick. Why? Because the Cro-Magnons were not only militarily much more advanced than the Eurasian Neanderthals, they were socially bonded into a single massive military group that can only be described as an army—or at the very least a proto-army. This was the strategic application of the new socialisation process—a process that effectively united the disparate tribes of Syria, Israel, Palestine, Jordan and other areas of the Levant into a single combative force that swept all before it.

As the raggle-taggle proto-army grew, a tipping point was reached, and the tide began to turn. The Cro-Magnon campaign accelerated its onslaught into a blitzkrieg. Over time, this search and destroy operation became genetically encoded in testosterone-charged adolescent and young adult males and continued unabated—generation after generation—until not a single Neanderthal was left alive from northern Turkey to Egypt.

This view is supported by the archaeology. John Shea concludes in Modern Human Origins and Neanderthal Extinctions in the Levant, “that around 45,000–35,000 BP, Neanderthal fossils cease to occur in the Levant at exactly the point when Upper Palaeolithic industries first appear in Israeli and Lebanese cave sites.”585

At the Amud Neanderthal cave, northwest of the Sea of Galilee in Israel, for instance, materials dated from the lowest levels of the cave reveals that Neanderthals first occupied the site 110,000 years ago (±8,000 years). The youngest date measured at the site comes from a single tooth from Level B1/6 which tells us the occupation ended 43,000 years ago (± 5000 years).586

Until recently, it was generally assumed that the disappearance of Eurasian Neanderthals from the Levant was caused by a deterioration in the climate. But in April 2008, at a meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, Miriam Belmaker from Harvard University deftly demonstrated that the climate in the Levant at the time of their extinction was stable, ruling out climate change as a factor in their disappearance.587

If NP theory is correct and Cro-Magnons were a hyper-aggressive new transitional species, purpose-built by natural selection to kill Neanderthals, then it follows that even after the disappearance of the last Neanderthal, Levantine males would simply disperse further afield in search of more victims. They had spent several thousand years relentlessly hunting their ancestral foe—this is what young Cro-Magnon males did—and they were not going to stop now.

But NP theory and an understanding of human nature also predicts something else happened: the proto-army of the Levant began to fall apart, and ultimately turned against itself.

The alpha males who, by force of strength and aggression, had maintained cohesion within the group became besieged by eager and ambitious young males determined to assume their mantle. Here, I suggest, is the origin of that unique and ubiquitous pattern of human group dynamics, distinguished by male intergroup competition, power plays, political divisions, leadership challenges, Machiavellian intrigues, betrayals, ‘civil war’ and chaos. The techniques that had been so effective in conquering Neanderthals had found a fertile new outlet within Cro-Magnon society

As the proto-army grew too large to be effectively managed, fed, organised and controlled, secondary leaders (beta males) saw an opportunity. Taking advantage of the increasing frustration, they agitated, conspired and aspired to be alpha males with access to all the fertile females. Leadership challenges became a constant fixture of the times. Retributions for unsuccessful coup attempts were swift and violent, and deposed leaders would be banished or killed. Dissent spread, disorder became the status quo and eventually some beta males broke away or were expelled, taking their warriors and their families with them. These smaller armies then spread out from the Levant to conquer and colonise their own territories.

While this scenario is, at best, informed conjecture, it is supported by the genetic and archaeological evidence, which reveals the Levant human population did split into at least three large groups that eventually dispersed out of the Levant at precisely that time.

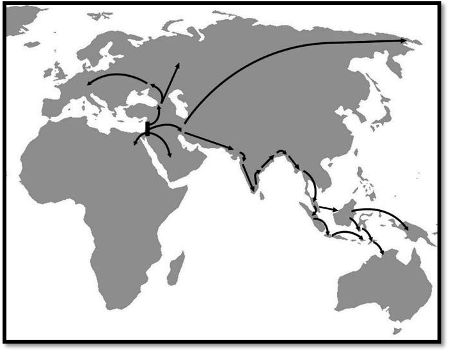

One group migrated east, around the coast of India into eastern Asia, and eventually across the Bering Plain (Beringia) to people the Americas.588,589

A second group dispersed from the Levant to Europe, while a third migrated back to Africa.590,591,592 These migrations all date to between 45,000 to 40,000 years ago.

Suggesting that the third group of Levantine humans migrated south into Africa—their ancestral homeland—is at odds with the long-held assumption that the world-wide dispersal of modern humans began in Africa. Corroborative evidence for the back migration theory only emerged in December 2006, via a landmark study of mitochondrial DNA from ancient human fossils by an international team of 15 geneticists lead by Antonio Torroni from the University of Pavia in Italy.593 The study, published in Science, reports that between 40,000 to 45,000 years ago, a group of modern humans living in the Levant split into genetically separate groups. Torroni traces one group as it moved north into Europe, and another that moved back to Africa.

The global expansion of modern humans began in the Levant and dispersed to Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia and the Americas, via a coastal, island-hopping route.

By measuring the amount of genetic diversity in the mtDNA and on the Y (male) chromosome, Torroni’s group concludes, “the first Upper Palaeolithic cultures in North Africa (Dabban) and Europe (Aurignacian) had a common source in the Levant”,594 spreading by migration from a core area in the Levant.

The Upper Palaeolithic Levantine people that Torroni refers to (that first appeared 46,000 to 45,000 years ago) dispersed to south-eastern Europe via Turkey around 43,000 years ago.595,596,597,598

The date of the dispersal from the Levant (45,000 to 40,000 years ago) agrees with the near-extinction hypothesis of NP theory and the emergence of a new human species as a consequence of Neanderthal predation.

The pace of this dispersal fits with my more nuanced view that Cro-Magnons, unlike their Middle Palaeolithic predecessors, were not averse to risk-taking, exploration or territorial expansion. It also supports NP theory’s proposal that the incursion into Europe was not a nonchalant nomadic migration in search of hunting and gathering opportunities, but a militaristic blitzkrieg by hyper-aggressive males inherently confident of their colonising and military capabilities. This indication of a new ‘conquistadorial’ component of human nature creates the impression that Cro-Magnons believed their technological and psychological superiority made them invincible—that nothing and no one could stand in their way. This was the first example of military expansionism, and it set the stage for the first real world war.