The seventh and final constraint on male hyper-aggression was ostensibly cultural. It was the uniquely human collection of laws, edicts, philosophies, conventions and collected wisdom

we call civilisation. Civilisation and the rule of law are normally used by sociologists to describe socially complex agricultural societies with large cities and developed economies. But from the perspective of NP theory, civilisation and the rule of law are much more. They are functional adaptations that contributed to fitness.

Civilisation and the rule of law involve such complex social, political, artistic and organisational systems, they require specialist neural networks and cerebral modules which, I argue, came under positive selection because civilisation was so effective in constraining male coalitionary violence. The cerebral modules that support civilisation spread rapidly because they allowed humans to apply cultural constraints to moderate maladaptive innate behaviours that had previously been all but immune from cultural control.

Like a Guttenberg printing press, civilisation churned out for the first time a plethora of moral and religious codes, laws, decrees and proto- governmental edicts to regulate social behaviour and, in particular, inappropriate violent behaviour by men. Prior to this, there was no formal mechanism for punishing offences against persons and property. It was left to tribesmen or relatives to punish the culprit, a practice which often escalated into broader conflicts.

The earliest example of coercive cultural management of male violence is probably the set of 57 laws, guidelines and edicts preserved on a small clay tablet by the king of Ur, Ur-Nammu (2112–2095 BC). Known as the Ur-Nammu law code, it begins:

Then did Ur-Nammu, the mighty man, the king of Ur, the king of Sumer and Akked, by the power of Nanna, the city’s king, and by the…, establish justice in the land, and by force of arms did he turn back evil and violence.

The Ur-Nammu code (below) provides the first real social antidote to collective senseless violence. One law, for example, reads, “If a man has severed with a weapon…bone of another man, he shall pay one mana of silver.”

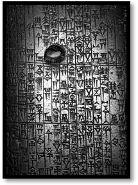

Three centuries later, in 1760 BC, King Hammurabi, the sixth Babylonian king enacted his own sets of laws—the famous Code of Hammurabi. It not only provided citizens with guidelines for acceptable behaviour, plus a detailed list of criminal offences and punishments, it also stipulated procedures for settling disputes peacefully. The code was carved onto a black stone stele (below), 2.4 metres (8 ft) tall, and was on constant public display, so no one could plead ignorance of the law.

For Babylonians contemplating a flirtation with villainy, a cursory glance at the stele might prompt a rethink. Examples include:

• If a man has stolen goods from a temple, or house, he shall be put to death; and he that has received the stolen property from him shall be put to death.

• If any one take a male or female slave of the court, or a male or female slave of a freed man, outside the city gates, he shall be put to death.

• If a man has stolen a child, he shall be put to death.

In all, there are 282 edicts, enough to cover most social situations and, while they may seem draconian by today’s standards, they didn’t hold a candle to the laws promulgated by the 7th century BC Greek legislator Draco. By imposing the death sentence for practically every offence, no matter how trivial, he gave his name to the word ‘draconian’.

While the Jewish Torah includes hundreds of commandments, the Judeo-Christian tradition condensed these into the Ten Commandments (or Decalogue) which incorporated several religious prohibitions along with its moral directives.

Central to all these cultural regulations is an unequivocal prohibition against gratuitous violence. And, in every case, the edicts are enforced by physical coercion. The punishments listed in the Yasa (or law) of Genghis Khan, the infamous Mongolian warlord, include:

• An adulterer is to be put to death without any regard as to whether he is married or not.

• Whoever is guilty of sodomy is also to be put to death.

• Whoever urinates into water or ashes is also to be put to death.

• Whoever finds a runaway slave or captive and does not return him to the person to whom he belongs is to be put to death.

For the three millennia following their introduction, cultural prohibitions continued to rein in male violence. When a group of rebellious English lords forced King John to sign the Magna Carta in 1215, they not only curtailed the worst excesses of his violent nature, they introduced several revolutionary new concepts into the campaign, including protection of the law, freedom, and a citizen’s right to feel safe:

No freeman shall be taken, or imprisoned, or disseised [dispossessed], or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed, nor will we go upon him, nor will we send upon him, except by legal judgement of his peers or by the law of the land… All persons are to be free to come and go, except outlaws and prisoners.

From a 21st century perspective, it is difficult to comprehend the social and political impact these edicts had. After five million years of the law of the jungle, with all its hostile connotations, here was a radical new concept that meant, for the first time in human history, people were not constantly looking over their shoulders.

Of course there was the massive gulf between intention and reality, exemplified by the English lords themselves whose motives for Magna Carta remained steadfastly those of self interest. But despite the glacially slow progress, by 1790 the Declaration of the Rights of Man of the French Revolution was empowered in a genuine attempt to curb the devastation of barbarism, anarchy and mob rule.

Not all the rules of law were written down. Indigenous Australians, custodians of the oldest continuous culture in the world, incorporated an holistic set of social and spiritual laws into a complex oral tradition, disseminated by ‘law men’ and tribal elders. Central to the law was the concept of payback which includes procedures for redressing grievances through ritual ceremony, gift-giving, corporal punishment, or even killing.766

In practical terms, it means that if an offence is committed by an individual, only the offender is punished, which prevents escalation into larger tribal conflicts. So successful was the law, Indigenous Australians remain one of the few nomadic people who did not need to construct walled cities and so could maintain their hunter-gatherer existence.

Whatever form they took, cultural mechanisms of control generally proved an effective means of curbing male violence. I see three main reasons for this:

• Most of the codes used violence to curb violence, with violators more often than not facing the death sentence. While this ‘eye for an eye’ may seem paradoxical, it doesn’t contradict human nature. Punishment, chastisement, reprisal, violence, ostracism, victimisation and marginalisation are all endemic to the human condition. We’re biologically au fait with them. They’re part of our inherited biology.

• The laws were edicts of ‘big men’—chiefs, kings, tribal elders and warlords—all surrogates of the ancestral alpha male who dictated behaviour in early human groups and, before that, in ancestral primate troops. Humans are genetically inclined to obey the alpha male—to comply with his dictates—particularly during times of stress because, historically, such obedience proved adaptive.

• The rule of law appealed to people’s altruistic, civil, generous, intellectual and familial sides. This was the carrot to complement the big stick. The philosophies of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Lao Tzu, Confucius, the pre- Socratic philosophers and the Pax Romana are prime examples of the appeal to reason and lucidity, as were the moral teachings attributed to Jesus of Nazareth and Mohammad.

This reassessment of civilisation argues that its greatest achievement was not art, language or the spread of technology. It was the rule of law. It functioned as an antidote to male hyper-aggression. The incorporation of both coercive measures and appeal to newly acquired reason and rationality allowed humanity to reach a tipping point where, despite continual warfare and intergroup hostilities, family life finally became sustainable.

This new appreciation of civilisation also illuminates its fragility. Civilisation is a bulwark between our arduous evolutionary legacy and viable continuance. In this book, space precludes a detailed discussion of the social, political and personal implications of NP theory for modern humans, but I feel an obligation to at least highlight both the tenuous nature of civilisation and the indispensable role it played in human evolution.

NP theory suggests that seven mechanisms emerged to mitigate the worst excesses of male coalitionary violence:

• Natural selection: the most violent men killed each other off and their genes were lost.

• Sexual selection: women preferred less violent men to father their children.

• The development of cognitive networks enabled logic and rationality to control innate aggressive tendencies.

• The evolution of a degree of tolerance of individual and cultural variability.

• The emergence of neural networks that supported complex society, and the aggregation of people into large groups for mutual protection.

• The invention of agriculture which enabled people to live in walled compounds.

• The advent of civilisation and the rule of law to culturally inhibit gratuitous interpersonal violence.

Scrolling down the seemingly endless lists of victims of human violence over the last few millennia begs the question—did these seven adaptations against male hyper-aggression do any good at all? They may have removed the ‘hyper-’, but we are still an undeniably aggressive species. Re- searchers have calculated that over the last thousand years, 11 European countries have been engaged in some form of warfare 47 percent of the time. The devoutly Catholic nation of Spain tops the list having spent 67 percent of the last millennium at war.767

To appreciate just how ingrained these predation imperatives are, we need only note that—despite the attrition of the most virulent male aggression genes throughout the Neolithic, despite the controls imposed by rules, laws and commandments, and despite the civilising influence of religion and philosophy—two global conflagrations, a holocaust, and countless genocides have occurred within living memory.

Humans remain a violent species and the prevalence of weapons of mass destruction ensures that our continuance as a species cannot be guaranteed. However, without these seven adaptations, humankind would have torn itself to pieces years ago.