Islamic Art and Material Culture in Africa

René A. Bravmann

To look at the arts and material culture of Islamic Africa is to engage a particularly vital frontier, one marked by the blending of belief and the artistic imagination. Africa is a long-ignored portion of Islamic civilization, a religious culture that has helped shape much of Africa and its creativity. Islamicists, however, have rarely been inclined to consider Africa (except for the heavily Arabized northern fringe of the continent): it has always been regarded as too provincial, too far removed from the heartland of Islam with its sophisticated metropolitan centers, imperial courts, and famed seats of learning. Located at the extreme edge of this civilization and conditioned by apparently different historical and cultural forces, Africa’s monuments and creativity, typically marginalized or ignored, remain an eternal other—they exist but go unnoticed and unattended.

That this continues to be the case can be seen in the spate of volumes and exhibition catalogs that have appeared since the mid-1970s, a period marked by a general resurgence of Western interest in things Islamic. Such works fail to reveal Africa’s contributions. Museums have been anxious to exhibit their Islamic holdings, and yet only the Heritage of Islam (along with a modest companion installation organized by David Heathcote and devoted to the arts and material culture of the Hausa of northern Nigeria), a highly successful international exhibition seen by large audiences both in Europe and the United States, touched upon Africa’s wider artistic role within the Islamic world.1

How, one must ask, has this come to pass? After all, Islam in Africa is nearly as old as the faith itself and has, over the past millennium and more, come to influence much of the continent north of the equatorial forest and east of the great Rift Valley. Even regions normally regarded by African Muslims themselves as dar al-harb, lands of unbelief, have often proved to be fertile soil for Muslims and their faith. For example, in this volume see the revealing chapter on South Africa (chapter 15); or see the many writings of Ivor Wilks and others based upon European and Arabic sources, that describe the vital links binding Muslims and non-Muslims in nineteenth-century Asante.2 That Islam has had a decided influence upon formal developments in architecture, weaving traditions, sculpture, and the decorative arts is now patently obvious, for everywhere one sees a blending of the message and requirements of the faith with local beliefs, values, and sensibilities. The resultant mix—never fixed; always in a state of dynamic adjustment and flux—tells us that Africa and Islam have surely made something of each other that is quite extraordinary, if only we care to look.

If the process of Islamization on the continent has in fact been so resonant, if it has resulted in such noteworthy achievements, why have they not been included in a wider vision of the Islamic phenomenon? Why not consider the diversity of mind and sensibility encountered in Hausaland or the Swahili coast in surveys of the Islamic world? Why do Islamicists persist in locating the cultural center of gravity of this religious civilization the way they have, thereby excluding vast portions of Muslim Africa? Karin Adahl, an art historian of Islam, begins to address precisely such questions in a recent essay but falls prey to many of the attitudes of her predecessors. For Adahl, much of Africa has not been considered by her colleagues because there are neither the necessary number of monographs nor the “comprehensive documentation of artifacts” that might allow for a history of the arts and material culture.3 She is, of course, correct on this point, for much remains to be done. Adahl then goes on to submit, with unusual academic candor, that the arts of Islamic Africa, except for those of the Maghreb and Egypt that fully conform to classic Islamic canons, have been ignored simply because they lack “a certain quality.” This is apparently due to the fact that in much of Muslim Africa “there is no court art, no major production centres for ceramics, carpets or manuscripts.”4 For Adahl, Islamic art and architecture, the high monuments and art forms of this civilization—the products of sophisticated metropolitan workshops that flourished over a period of centuries “in the central Islamic world, i.e., from Spain to India, from Turkey to Egypt”—are qualitatively different from that found in Africa. The perfection of form for Adahl, achieved in the arts of “glass, metalwork, woodwork, ivory, textiles, carpets, book-making, and painting” by Muslim artists in the heartlands of Islam, is simply not to be found in Africa. There Muslim creativity has been of another order, a pale and distant reflection of high Islamic culture and the home of only “simple and mostly second rate items.”5

Adahl’s essay serves as the introduction to Islamic Art and Culture in Sub-Saharan Africa, a volume published in 1995, edited by Adahl and her colleague Berit Sahlstrom and based upon papers delivered at an international conference hosted by Uppsala in 1992.6 The thrust of this gathering was to explore Africa’s contribution to Islamic civilization; it included participants from the disciplines of archeology, cultural anthropology, art and architectural history, and aesthetics. Adahl was one of the conveners of the conference and a founding member of the Uppsala Research Group for African and Islamic art. A specialist in Islamic art, with particular expertise in the Khamsa of Nizami and the broader topic of orientalism, she has more recently developed an interest in the subject of African Islam based upon a residency in Libya and travels in West Africa.

Adahl’s introductory essay is an attempt to define what is Islamic in the arts and material culture of Muslim Africa and how this relates to creativity in the wider Muslim world—a daunting task, especially for someone with a traditional grounding in the arts of Islam, and one who is a relative newcomer to the subject of Islam in Africa. The resulting work shows that Adahl, while sympathetic, is never quite sure how to define the arts of the continent, for she is never really able to shed her centrist notions of what constitutes Islamic art, never really able to escape her training and intellectual perspective. The creative tension between Islam and African societies and the very process of Islamization itself are not addressed, although a number of the contributions in the volume touch upon this vital theme. In the end, Adahl would have done well to hearken to the words of Clifford Geertz, who so brilliantly explored the development of the faith in Morocco and Indonesia in Islam Observed many years ago. Why, Geertz asks, are Morocco and Indonesia so different despite being influenced by a single creed? What is it about Islam and local cultures, about the blending of so called “Great” and “Little” traditions, that results in such contrasting Islamic civilizations? For Geertz the process of Islamization is crucial, as is true in this volume, and it must be examined in a sensitively balanced manner. His words resonate for anyone attempting to understand the nature and character of African Islam:

In both societies [Moroccan and Indonesian], despite the radical differences in the actual historical course and ultimate (that is contemporary) outcome of their religious development, Islamization has been a two-sided process. On the one hand, it has consisted of an effort to adapt a universal, in theory standardized and essentially unchangeable, and unusually well-integrated system of ritual and belief to the realities of local, even individual, moral and metaphysical perception. On the other, it has consisted of a struggle to maintain, in the face of this adaptive flexibility, the identity of Islam not just as religion in general but as the particular directives communicated by God to mankind through the preemptory prophecies of Muhammad.7

If Adahl had heeded Geertz’s words it might have helped to decenter her narrative and allowed her to pursue her goal of trying to define “what is Islamic” about the arts of Muslim Africa in a more satisfying manner.

If Islamicists continue to ignore Africa, it is also true, as John Picton noted in his illuminating contribution to the Uppsala conference, that Africanists interested in the arts and material culture of the continent often fail “to reveal the presence of Islam.”8 While Picton’s chapter “Islam, Artifact and Identity in South-western Nigeria” is important in many respects here, I simply want to touch upon some of his thoughts regarding Yoruba identity and Islam. The Yoruba present us with a particularly poignant case of not revealing Islam, for this culture and its artistry have been the subject of intense scrutiny since the late-colonial period. The scholarly literature on the Yoruba is vast, surely the largest for any African society, and includes some of the most discerning studies we have from the continent. Yoruba have themselves contributed impressively to this bibliography, especially in the field of aesthetics, where fluency in the language and a sensitivity to the expressive modes and nuances of culture have been critical. Trailblazing examinations of the relationship of art to society and especially of the religious, social, and political dimensions of Yoruba creativity appear almost annually and continue to probe the subtle links between art, music, dance, oratory, and drama that mark this civilization.

What we know about Yoruba artists and their careers is impressive; in fact, at the time this chapter was being written, people in New York were viewing the exhibition “Master Hand: Individuality and Creativity among Yoruba Sculptors” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—the result of nearly two generations of critical inquiry beginning with the work of Father Kevin Carroll and more recently undertaken by Abiodun, Drewal, and Pemberton.9 This was not a typical exhibition of objects by anonymous African craftsmen but rather a close examination of the works and lives of thirty influential Yoruba artists, a curatorial feat that is simply not possible for any other African culture.

Picton challenges our very assumptions about what we have come to call Yoruba, and demonstrates just how crucial the Fulani jihads of the nineteenth century were in the fashioning of Yoruba identity and consciousness. Islam began rather modestly among the Yoruba in the 1840s, but its influence grew dramatically, especially in western and northern Yorubaland, so that by the end of the colonial period, nearly 50 percent of the population regarded themselves as believers. That Islam has become an important part of Yoruba life in this century should be self-evident, and yet, as Picton notes, the substantial literature on this culture and its artistry remains curiously silent on the subject.10

What we do learn emerges from almost parenthetical observations: that Lamidi Fakeye and Yesefu Ejigboye, two well-known Yoruba sculptors, are practicing Muslims; that Oyo leatherworking derives much of its inspiration and vigor from Muslim Nupe and Hausa models; that Ifa divination, so crucial to Yoruba religious and social life, shares many features with Muslim Yoruba divining techniques and practices. Such snippets of information are, of course, intriguing, but they do not begin to challenge seriously our old and outdated notions of a pristine and monolithic Yoruba society. We urgently need cultural studies that seriously consider the Islamic factor in Yorubaland, as was done over twenty years ago by the historian Gbadamosi in his important book The Growth of Islam among the Yoruba, 1848–1908.11 To continue to ignore this crucial aspect of Yoruba history and identity will never allow us to measure the fullness of the culture’s social and artistic imagination. I would like to submit, in accord with Picton’s admonition, that we will never truly grasp what has taken place in Yorubaland, or engage the history in and of the arts over the last century and a half, until we begin to address the impact of Islam upon Yoruba society.

Although it is a rather glaring example, Yorubaland is simply one instance of our unwillingness to take into account the influence of Islam. It happens elsewhere, and because so many Africanists (art historians, anthropologists, and so on) continue to “fail to reveal” the Islamic presence, it skews and often distorts our very vision of African creativity. The western Sudan, specifically the area included within the modern-day Republic of Mali—a region long subject to the process of Islamization—presents us with a number of such cases of neglect. Dogon art and culture, for example, long hailed as exemplars of traditional Sudanic civilization and a people ever vigilant to the potential encroachment of Islam, cannot be fully understood or appreciated without considering the impact of Muslim mystical texts like the Kabbe, written early in this century by the Fulani cleric and scholar Cerno Bokar of Bandiagara and apparently utilized in Dogon rituals today.12

Songhay spirit possession (ghimbala), so prevalent throughout the inland Niger Delta of eastern Mali, can ultimately make sense only if we acknowledge how it was reshaped during the nineteenth century by the Muslim reformer Shaykh Amadu of Masina. Ghimbala today, according to Gibbal, is the result of extraordinary accommodations, a blending of Quranic and Songhay invocations, of ritual acts said to be prescribed by the Quran and sanctioned by the ancient spirits that have always inhabited this Songhay-dominated portion of the Niger River.13 Possession ceremonies today still follow an ancient calendric cycle, but out of deference to Muslim sensibilities, especially those shaped by the fundamentalist strain of Islam that has emerged in recent years in Mali, they are no longer held during the month of Ramadan. Such fusion and blending of tradition and Islam is perhaps best expressed by one of Sarah Brett-Smith’s Bamana informants, the sculptor-blacksmith Kojugu: “We cite the owners of the Qur’an (i.e. Muslims) and the owners of the Qur’an cite us. All these things are mixed up together (i.e. all the beliefs current in the Mande world, both Islamic and traditional are interdependent).”14 In Brett-Smith’s stellar volume The Making of Bamana Sculpture, one is never far removed from the presence of Islam; it is always there lurking in the shadows of this monumental study, but, as she asserts in her introduction, given the thrust of the work it is a dimension that will have to “be left to others to investigate.”15

Having said this, let me temper these comments by noting that important contributions on the arts and material culture of Islam, the result of impressive field-work and penetrating analysis, have begun to appear in the last two decades. These contributions are indeed rich, as well as full of promise for future research.16 They tell us that Trimingham’s bleak evaluations of the impact of Islam on African creativity, found in his pioneering work from the late-colonial period, need to be seriously reexamined. For Trimingham, the process of Islamization was inimical to African artistry and material culture because it could and would not tolerate their intimate connection to traditional values and beliefs. Conversion to Islam, it was his contention, invariably resulted in the rooting out of animist symbols, and when these were displaced “there [was] no aesthetic need to be satisfied which might be diverted to other artistic concerns.”17 In addition, the strong aniconic stance of the faith was considered a certain death knell for African visual and symbolic systems.

Although it is still too early to write a comprehensive history of the arts and material culture of African Islam, given the large gaps in our knowledge, what can be demonstrated at this time is that the faith has forged a special and enduring relationship with its followers and that the arts of this vast area of Africa belong fully within the Islamic orbit. They serve as a vital testament to the remarkable diversity of mind and sensibility found within Islamic civilization, and they are, for me, among its most unique and enduring expressions. Never merely passive recipients of Islam, African members of the community of believers (the umma) shaped the religion whenever and wherever necessary to fit local needs and circumstances. Making something of each other, a synthesis developed that has proven to be rich and enduring. For the purposes of this chapter, I want to focus upon certain themes that strike me as particularly apposite in any attempt to begin to comprehend the artistry and character of African Islam. The discerning reader will notice that many of these themes are precisely those identified by scholars when more broadly discussing the arts and monuments within Islamic civilization.

I want to begin with the Word—the ways in which Allah’s message, as embodied in the Quran, enriches and lends meaning to life itself. A passion for the words of God is evident everywhere in Muslim Africa so that, as Geertz noted in his study of Moroccan Islam, “the most mundane subjects seem set in a sacred frame.”18 These sounds and phrases of Allah lend a special tonality to existence; they create for the believer a potent acoustic quality to God’s omnipresence, and they ultimately lie at the very heart of Muslim artistry. As I have noted elsewhere:

The faithful not only feel and hear Allah’s presence about them, they can actually see and touch it, for African Muslims transform the words of God, this passion for His sound, into clear and immutable shapes. African aesthetic sensibility merges everywhere with the literary and graphic potential of Islam, bringing a particular stability and form to God’s words. African Islam … calls upon the skills of its scribes and scholars, as well as the cunning of its artists, to make visible God’s presence in this world.19

To paint or weave God’s words is to create from the deepest of sources, to produce works whose coercive power and affective beauty are undeniable.

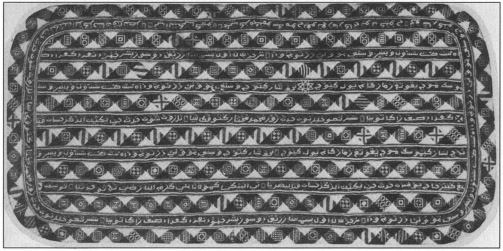

One encounters numerous examples of these transformations of the words of Allah, the language of the Quran, on the African continent. Here I will consider a few of them. The first is a woven mat of natural and dyed grasses, an especially fine product of Muslim Swahili plaiting, that is located in the Tanzania National Museum collection (fig. 1). Most likely made within the last two generations, it is a splendid example of a much older tradition of prayer mats documented by the German ethnographer Franz Stuhlmann at the turn of the nineteenth century.20 Woven in the village of Moa, near the important coastal town of Tanga in northern Tanzania, it exhibits all the love for geometric pattern generally found in Swahili prayer mats, known as mswala. What distinguishes this mswala, and several examples collected near Moa by Stuhlmann for the Hamburgischen Kolonialinstitut nearly a century ago, is that the rhythms of geometry are framed and banded by God’s words. Somehow, the artist managed to weave into this “place of prayer” (the literal meaning of the word mswala) Swahili verse rendered in Arabic characters. The script occurs within five narrow bands that run virtually the full length of the mat and in another band just inside its border. These strips are separated by woven bands consisting of geometric patterns; all is then edge-sewn to produce the mat. The bands of script are punctuated at regular intervals by the stirring invocation “In the name of God,” known as the bismillah, while Allah’s praise-name Karamallah, or “God the beneficent,” occurs at several points throughout. A single reference to Muhammad the chosen prophet is to be found in the very center of the mat. The verses themselves are difficult to decipher for, according to Seyed Muhammad Maulana, a colleague from Mombasa, Kenya, they appear to be executed in a very localized script. What one cannot fail to appreciate, however, is that the weaver from Moa, using the humblest of materials, literally wove his passion for God and the prophet into a “place of prayer.”21

Fig. 1. Woven into this Swahili prayer mat (mswala) from northern Tanzania are references to Allah and to Muhammad the Chosen Prophet “Muhammadi Muhutari Nabiya.” Tanzania National Museum Collection.

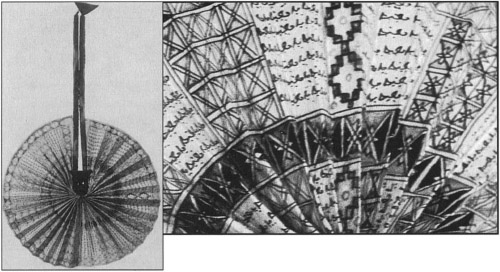

Figs. 2a and b. This prestige fan, collected in northern Togo by Captain Thierry, a German Colonial administrator at the turn of the century, includes numerous references to one of Allah’s 99 names, Ya Hafiz—“Oh Protector” or “Oh Guardian”—along its outer edge. Field Museum of Natural History. #104.941.

Calligraphy is one of the great art forms of Islam, the visual equivalent to Quranic chanting, and some of the most dramatic examples of this tradition come from the African continent. An unusual piece in the collection of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago demonstrates that African Muslim artists are masters at presenting their passion for the word of God. A prestige fan, possibly of Hausa origin, is full of references to one of the ninety-nine excellent names of God, the Asma al-Husna, found in the Quran (fig. 2). Collected by Captain Thierry (a German colonial administrator stationed at the important trading town of Sansanne Mango in northern Togo) and acquired by the Field Museum in 1905, it is a calligraphic tour de force. Along the outer edge of the paper fan appears God’s praise-name Ya Hafiz, meaning “Oh Protector,” or “Oh Guardian,” while the inner band includes the phrase “May God protect and preserve.”22 The fan, to be held by someone of high rank (it reminds me of a paper shield covered with calligraphic inscriptions held by the Asantehene Opoku Ware at his installation ceremony in Kumase in 1970) dramatically displays God’s shielding presence.

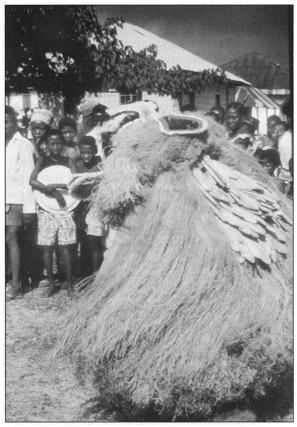

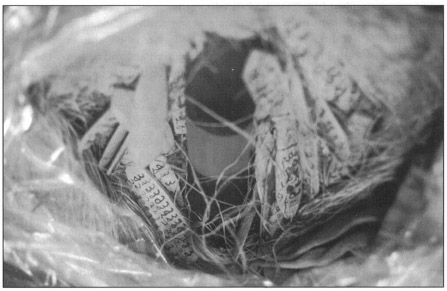

That God’s sounds and words are indeed ubiquitous, that they are incapable of being confined and therefore may be heard and seen in the most remarkable places, is revealed in a striking Goboi masquerade costume located in the University of Pennsylvania Museum and collected in the Mende chiefdom of Bumpe in the 1920s. Goboi masqueraders perform at virtually all functions of the Poro Society, the male secret organization so important to Mende culture. Goboi are entertainers of a high order and their striking costumes combine an abundance of raffia fiber, blue-and-white striped cotton cloth, cuts of red, black, and white homespun, mirrors, cowry shells, goatskin, and animal hair. In and of themselves, these are scintillating masked figures that cannot fail to please. But what ultimately fascinates the eye are the hampers, worn on the dancers’ backs, which often contain bundles of miniature Quranic tablets with what appears to be Arabic script painted upon them. Such a Goboi was photographed in performance by William Hommel while in Mende country in 1973 (fig. 3). The hamper attached to the Goboi costume in the Pennsylvania museum collection is particularly well endowed with tablets—fifty-six to be exact—each of which has been painted with the dramatic proclamation Ya Allah (Oh God!) (fig. 4). This Goboi, from Mende country, an area of Sierra Leone still only lightly touched by Islam, reveals that even when traditional values and artistry remain vital, one can enter a world where Allah and African creativity meet and mingle.23

Fig. 3. A Goboi masquerader photographed by William Hommel among the Mende of Kenema District, Sierra Leone in 1973. A collection of small wooden tablets with arabic inscriptions is visible in the hamper worn on the back of this Goboi.

Fig. 4. Fifty-four miniature Quranic tablets with Arabic script are located in the hamper of a Goboi costume collected in the Mende Chiefdom of Bumpe sometime during the 1920S. University Museum, University of Pennsylvania.

God’s words are not only rendered visibly but they exist as well in a very different domain—that ineluctable environment of silence and secrecy within which amulets or talismans are conceived (see chapter 21). Quranic talismans have always been an important aspect of African Muslim life, a fact confirmed by nearly all visitors to the continent and by some of the extraordinary terra-cotta sculptures from the area of Jenne in Mali (dated from the eleventh to fourteenth centuries) that depict figures wearing leather-enclosed charms. The range of talismans created by Muslims in Africa is extraordinary: their shapes and the materials employed stagger the imagination; yet all amulets are alike in that they contain concealed truths. Whether written on paper and covered with carefully worked and dyed leather, or encased in copper or silver boxes, or held in a liquid suspension kept in a vial or carved bottle, like the Somali quluc, amulets are nearly always shielded from the public eye and kept within a culture’s shadows. The owner of an amulet is the keeper of potent knowledge that is based upon carefully arranged and organized secrets, and thus is someone who possesses a particular treasure that cannot be known or shared by anyone else.

African Islamic charms, regardless of their outward form or intended purpose, appear to be composed of two parts—a written portion and a design or graphic element. Edmond Doutté, in his classic volume Magie et Religion dans l’Afrique du Nord, refers to these two elements as the daʿwa, or spell, and the jadwal, or picture.24 Some amulets include only a dawa; others have only a jadwal, with little or no writing; but many are glorious and creative works that combine the strengths of both elements. The daʿwa may derive from a number of Islamic sources, including the Quran (surely the single most important reference), astrological treatises and divination manuals, or books on numerology; the jadwal may be based upon magical squares, images of the planets and their movements, or an impressive variety of geometric configurations. Famous makers of talismans devote years to perfecting their craft, for they must not only be well grounded in zahir (the study of the Quran, the commentaries upon the holy book, and exegesis), but they also need to pursue the study of batin, the inner and mystical aspects of the faith. Batin studies is a vast realm, one that cannot be fully encompassed by even the most dedicated individual, but those that persist are said to come to an understanding of not only the many forces at play in the world but of the hidden faces of God.

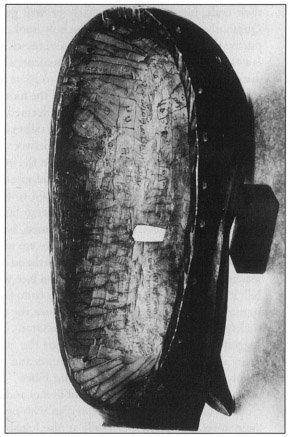

Since chapter 21 is almost wholly devoted to the topic of amulets, I want to confine my discussion to one example, a talisman that dramatically reveals what can happen in the continual interaction between Muslim and non-Muslim life in Africa. This particular amulet is found on the inner face of a mask, which in itself is a sculptural statement of inscrutable and mysterious forces, and therefore we are presented with an image that may be said to blend one secret with another. This Poro society mask (fig. 5), acquired in 1926 (and, like the Goboi costume, in the museum at the University of Pennsylvania), is attributed to the Toma of the Republic of Guinea. Poro masks, and there are many of them, are manifestations of the spiritual forces that guide this brotherhood and serve as guardians of its deepest secrets. This example combines a human face with the powerful beak of the hornbill; it thus instantly directs the mind to complex and barely understood notions of transformation. This could well have been the mask of a senior official of the Poro society, but we cannot be sure. What is certain, however, is that the face of the mask suggests powerful forces, and that inside the mask, on its inner surface, are drawn many squares that contain magical letters and numbers and a cryptic reference to chapter 3 of the Quran entitled “Palm Fiber.” This short chapter is also known as the sura of Abu Lahab (the father of flame) and speaks of one of Muhammad’s uncles, the only member of his own clan who opposed the prophet.25 Sura 111 is an angry invective hurled specifically at Abu Lahab and his wife: it is also known as the cursing sura, and is generally voiced at moments of betrayal and treachery. This is fitting, for whatever else is expected of this Poro society mask, it surely must stand as an obdurate sentinel ever ready to defend this secret organization and its members against treason from within.

A passion for the word of God and the ardent desire for talismans merges most dramatically in a specific period of African Islamic history, the nineteenth century jihads that occurred across the continent from Senegal to the Red Sea. The nineteenth century is filled with the names of Muslim leaders, religious reformers and militant nationalists who sought to purify and reinvigorate Islam and stem the tides of European encroachment. Among the former, surely the most famous was the Fulani social reformer and mystic ʿUthman dan Fodio, whose holy war against the Hausa states was permanently to change the political face and tenor of Islamic life in northern Nigeria. Of the militant resistors, the careers of al-Hajj ʿUmar, the Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad, and Muhammad Abdallah Hassan are remarkable for their unbending resistance to European force and their efforts to establish new political realms based upon Islamic principles. All of them fought against their oppressors and carried out a sacred religious obligation, by wielding the “sword of truth” and by waging battle “in the way of God.”26 To look at the swords, military banners, and other items associated with such campaigns allows us entry into the very nature of jihad, a duty sanctioned by the Quran and used by the Prophet himself in his attempt to spread the boundaries of nascent Islam. These objects are full of the very spirit and reality of holy war, for they include sacred words, cabalistic signs, and elaborate talismans that testify to the ever-present and guiding spirit of Allah.

Fig. 5. The inner surfoce of a Poro mask with powerful magical squares, letters, numbers, and a reference to chapter 3 of the Quran known as the Cursing Sura, or the Sura of Abu Lahab. University Museum, University of Pennsylvania. #Afs373.

One of the most protracted and bitter of the nineteenth-century jihads was the resistance movement, the Mahdiyya, waged between 1881 and 1895 by the Sudanese spiritual leader Muhammad Ahmad, the self-proclaimed Mahdi, or Messiah, against the combined might of British and Egyptian forces. The Mahdiyya had been active for nearly fifteen years when its leader died on 22 June 1895, nearly six months after the fall of Khartoum to the Mahdi’s forces and the death of General Gordon. This crushing defeat had a profound effect upon Queen Victoria and the British Parliament and led to new and even more ferocious encounters between the British and the Mahdists. Khalipha ʿAbdullahi, the Mahdi’s successor, bore the full fury of British revenge, and in decisive battles at Atbara and Omdurman, Anglo-Egyptian forces under Herbert Horatio Kitchener routed the khalipha’s armies. By late 1899, the calipha himself was mortally wounded at the battle of Om-Dubraikat, shattering the final hopes of a Mahdist state and making the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan a colonial reality. In the full flush of victory, British troops returned home with a veritable cache of booty taken from their fallen victims. The sheer quantity of war trophies taken back to England was an impressive testament to the epic dimensions of the war waged against the Mahdists.

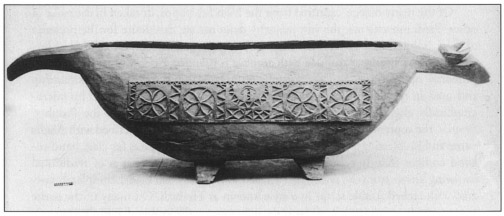

Among the spoils of war acquired by the British was a large, wooden slit drum, carved in the shape of a bullock, captured by Kitchener from the khalipha at the battle of Omdurma (fig. 6). The drum was presented to Queen Victoria by Kitchener, who was rewarded with a peerage for his role as commander at Omdurman and for ultimately crushing the Mahdist movement. The drum has been in the British Museum since 1937, a gift from King George V.27 While such drums have long been associated with important traditional chiefs and leaders in the southern Sudan and adjacent portions of the Central African Republic, they are generally much smaller and devoid of surface decoration. The calipha’s drum is not only monumental, perhaps testifying to his exalted status as the successor to the Mahdi, but it has been heightened sculpturally to fit within a militant Islamic context: “Mathematically precise floral patterns, a fretted crescent, meander (designs) and a single reference to a long-bladed scimitar are carved in broad bands across the flank surfaces, their geometric regularity and precision reminiscent of ancient Islamic shapes expressing God’s unity and presence.”28 Emblazoned with Muslim patterns, the booming sounds of this massively sculpted drum must have surely encouraged the khalipha’s followers in battle.

Fig. 6. Wooden slit drum captured from the Khalifa at the battle of Omdurman in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan and presented to Queen Victoria by Lord Kitchener, commander at Omdurman. The Trustees of the British Museum, 1937. 11–8.1.

That this jihad was waged with prayers, weapons, and a passionate belief in the holiness of their cause can be seen in the armor of faith that protected the Mahdl’s soldiers confronting the might of the British Empire. A particularly fine sketch of the fervor and passion of holy war are the words written by Sir Charles Wilson, who described the courage of one of the Mahdl’s commanders killed in the fierce battle near the wells of Abu Tlaih:

I saw a fine old shaikh on horseback plant his banner in the center of the square, behind the camels. He was at once shot down falling on his banner. He turned out to be Musa, Amir of Daigham Arabs, from Kurdufan. I had noticed him in the advance, with his banner in one hand and a book of prayers in the other, and never saw anything finer. The old man never swerved to the right or left, and never ceased chanting his prayers until he had planted his banner in our square. If any man deserved a place in the Moslem paradise he did.29

Chanted prayers shielded the faithful, as did the many cotton banners and flags carried by mounted warriors that were filled with appliquéed exhortations regarding man’s sacred military duty. One such flag, cited by Picton and Mack, contains the following message in Arabic: “Oh God, the Compassionate, the Merciful, the Living, the Eternal, the Almighty. There is no god but God and Muhammad is the Messenger of God. Muhammad al-Mahdi is the successor of the Messenger of God.”30 It is a message that would have elevated the spirits of the Mahdi’s troops, a flag imbued with special amuletic properties and expressing the sacredness of holy war.

Of the many objects captured from the Mahdist troops, or taken in the wake of other jihadi movements, the vast majority demonstrate this desire for the presence of God. Soldiers and cavalrymen went to battle dressed in robes, quilted clothing, and protective headgear studded with amulets containing God’s words. Chain mail, primarily of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Mamluk Egyptian workmanship and used in the Fulani jihads in northern Nigeria, was often enhanced by micrographically engraved individual links with references to Allah and the Prophet. Swords, the supreme Muslim fighting weapon, were invariably inscribed with Allah’s name and his blessings, while shorter, axe-like, branched weapons for close hand-tohand combat (faintly echoing the longer and more elegant shapes of traditional throwing knives from the regions of Wadai and Dar Fur) had blades completely covered with etched Arabic script in a style known as Thuluth. On many of the battle axes, readable script is replaced by pure arabesques, calligraphic shapes that are neither Arabic consonants nor vowels, but even in such examples the intent is obvious and dramatic. The incessant quality of such unreadable etching reveals yet another level of communication, the ardent desire of the craftsman to capture the grace and flow of God’s language thereby affording the weapon and its owner Allah’s shielding presence and protection.

A particularly rich arena for exploring the relationship of Islam to Africa and for examining the artistic results of this blending lies within the realm of Muslim festivals. Muslim holy days are impressive ritual events in which meaning is both created and released, and because they are often complex, unfolding over time, they have a rhythm and life of their own that can be contemplated and examined. To look even briefly at such festivals is to engage the remarkable diversity of mind and practice found within African Islam, to witness public demonstrations of communal belief and vivid enactments of religious sentiment. Festivals, by their very nature, enable the viewer to confront the full force of culture and artistry at work, to appreciate how they shape and focus the religious and expressive needs of believers. To look ever so briefly at Ramadan, the obligatory month of the fast, in two African communities—the Juula of Bobo-Dioulasso in Burkina Faso and the Gnawa of Marrakesh, Morocco—should demonstrate how this important religious obligation has been shaped by local values and sensibilities.31

For the Juula and Gnawa, the great fast of Ramadan is truly arduous, the day-light hours testing the believers resolve and devoted to reflection and self-examination. Fasting is crucial, indeed it is one of the five pillars of the faith, and its rigors are readily visible in both communities. Juula neighborhoods, normally distinguished by their intense commercial activity, are remarkably muted places during the daylight hours of Ramadan, while the Gnawa, nearly always a vital part of the J’Ma el Fnaa of Marrakesh, conspicuously absent themselves from the social heart of the city. Attendance at mosques increases dramatically and people spend much of their time reading large portions of the Quran and listening to the words of teachers and religious elders. Juula and Gnawa seek to observe the fast faithfully, for to follow God’s directives during this month is said to be much more beneficial than at other times in the year.

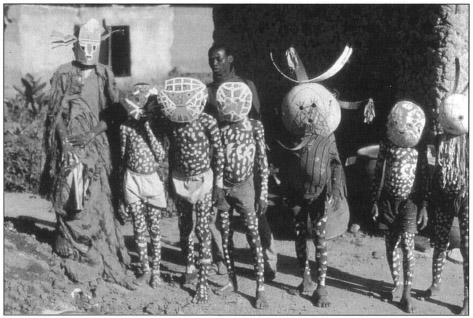

The nights of Ramadan bring a release from the demands of the fast, and the Juula and Gnawa follow those words of the Quran that serve as a guide for night-time behavior: “Eat and drink, until the white thread shows clearly to you from the black thread at dawn.”32 Entertainment and feasting are a very conspicuous feature of night life at Ramadan, but among the Juula and Gnawa, these nights, and especially those toward the end of the fast and the succeeding month, are highlighted by an unusual degree of creativity. In Bobo-Dioulasso, on any given evening, Juula children between the ages of six and fifteen perform dodo, a masquerade that includes stock animal and human characters and is wholly orchestrated and directed by the older children. Masks and costumes are created from pieces of tattered cloth, scraps of cardboard, discarded gourds, indeed whatever can be salvaged from the world around them, and the results are a pure celebration of the artistry and ingenuity of childhood (fig. 7). A chorus of youthful voices, accompanied by drum rhythms rendered on old tin cans, sing songs appropriate to each of the masked characters. Children in Berrima and other Marrakshi neighborhoods where the Gnawa are concentrated also regale their elders with song and musical compositions, knowing full well that their efforts will be rewarded, for the nights of Ramadan call for people to demonstrate their generosity.

Fig. 7. Members of a dodo troupe in the final stages of preparation for their Ramadan performance. Photograph taken by the author in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso in October 1972.

In each community, the eve of the twenty-seventh of Ramadan, known as the Lailat al-kadr, or the Night of Power, is especially important, for it was on this night that Allah first revealed the Quran to the Prophet Muhammad.33 The unique character and magic of this night is explicitly stated in chapter 97 of the Quran, and both the Juula and Gnawa believe that evil spirits, or jinn, that have been bound by God’s angels since the onset of Ramadan, are now even more fully secured, allowing the good angels and the spirit of God to descend into the world. Gnawa court-yards are carefully swept and washed, and special incense is burned in their corners to attract God’s shielding presence. Gnawa homes require special protection at this time, for at the end of Ramadan the jinn will again be released to the world of the living, to their human hosts, and will need to be placated anew through nightlong possession ceremonies (derdeba). Juula demonstrate their joy at Lailat al-Qadr with spectacular dances in which members from each of the Juula lineages perform. Unmarried girls, dressed in white waistcloths and covered with gold and silver jewelry, are led by a single dancer clad only in briefs and strands of colorful waist beads. Each of the leaders’ bodies is covered with beautifully patterned designs painted with a mixture of rice flour and water, and each carries upon her head a set of stacked brass or imported enamel basins, from six to eight basins tall, that contain medicines and cowries and are tied in a string net. Drumming and dancing continue until just before dawn—an elegant display of that special Juula sensibility for parading their joy and closeness to God.

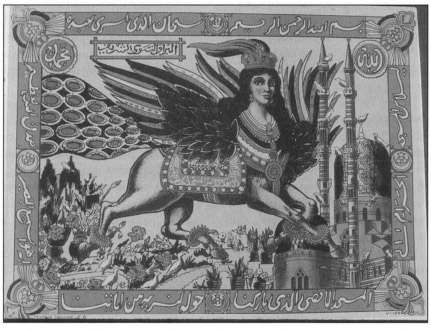

Muslim Africa is also home to a fascinating tradition of popular prints devoted to religious subjects such as Muhammad’s heroic battle at Badr, pilgrims on the hajj, a saint’s tomb, and a generalized rendering of the Mosque of the Dome of the Rock. Printing houses in Egypt, Algeria, and Tunisia have spawned something of a minor industry, for these colorful prints are mass produced and affordable. They can be found for sale in markets and shops throughout much of West Africa and seen occupying an honored place on a sitting room wall in Muslim homes. Of all the subjects treated, surely the most popular is the one of al-Buraq, Muhammad’s winged horse, which is said to have carried the Prophet on his mystical night journey (isra) from Mecca to Jerusalem and then on his nocturnal ascent (miʿraj) to the Dome of the Seven Heavens. A particularly fine example, most likely printed in Algeria, was collected in Ghana in the 1940s (fig. 8). The principal colors of this print are deep reds and plum, and they are particularly rich. The work is also more finely detailed than more recent examples and is more generously endowed with religious inscriptions: the first verse of sura 17, known as the Israelite, or the night journey, appears within the border of the print; references to Muhammad, Allah and al-Buraq are located in various medallions and around the saddle blanket; al-Buraq is extolled once again: “Praised be he who carried his servant (to) the distant mosque.”34

Fig. 8. This print of al-Buraq was collected in Ghana in the late 1940s. Within the border surrounding the print is the first verse of sura 17 known as the Night Journey. In the rectangular box above the wings is the praise “al-Buraq, the Noble and Sympathetic Friend.” Hearst Museum of Anthropology, Berkeley.

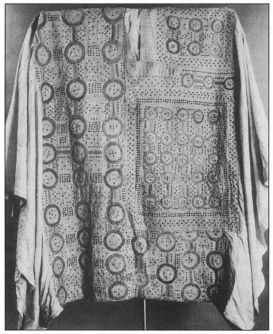

Not only is the print of al-Buraq particularly popular in much of West Africa, but it also seems to have served as a visual catalyst for the many renditions of the winged steed currently being created by Muslim textile artists and scribes. Depictions of al-Buraq, often handled in a highly stylized manner, occur in numerous amulets from Sierra Leone, where they are elaborated with portions of Islamic verse. Left unfolded and placed above entryways, such charms are said to be particularly effective sentinels against evil forces, especially tasalima, or witches. Within the shimmering iridescence of Yoruba indigo tie-dyed cloths (adire), a common theme is the crowned and winged al-Buraq with peacock tail-feathers, depicted as if on its mystical journey through a dark-blue night sky. The image of al-Buraq has even been absorbed into the contemporary world of advertising, for Nigerians can now sleep peacefully under “the blanket of your dreams,” made of blended viscose by Mantex Manufacturing of Kano, and known commercially as Flying Horse Blankets.35 The registered logo of this covering is a small image of al-Buraq in flight, although in this instance, the female-headed steed is openly smiling at the viewer; it may well suggest the sweetness of commercial success (fig. 9).

Images like those of al-Buraq are certainly fascinating, for they reveal the iconic potential tapped by Muslim artists in Africa. There is yet another face to Muslim creativity, however, that is much more common and visible—an artistry that conspicuously avoids representation in favor of a passionate pursuit of abstract shapes, a love of geometric patterns, sumptuous colors and exquisite textures. To look at such objects is to confront a world of humble items—cushions, robes, textiles, baskets, and jewelry—the things that we in the West classify as the “minor arts.” In the hands of Muslim artists, however, these things are so consummately worked, so thoroughly ennobled, that they cannot fail to claim our attention.

A preference for beautifying the surface of objects with pure design has always marked the arts of Islam, has always been the dominant expressive mode of Muslim cultures, for religious dogma and theological opinion have consistently rejected the use of imagery as a valid avenue for the artistic imagination. That this orthodox authority could be ignored can be seen in artistry and monuments from much of the Islamic world, yet such proscriptions did have a decided effect for they fostered a particular outlook, a cast of mind and sensibility, that was to encourage the special delight for surface decoration and design that has come to exemplify the arts of Islam.

In any African Muslim community one quickly observes this particular aesthetic predilection. Humble objects—stools, ceramic containers, cushions, gowns, and hats—are all intensely personal items, but they are created and elaborated in such ways as to grace the lives of their owners. Surface patterns that initially appear to have been spontaneously created are in fact carefully planned and executed, sharing a level of refinement and formality found in the people themselves. Take for example a richly embroidered full-length man’s gown (riga) from Kano, Nigeria, in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 10). This voluminous Hausa garment is made of white cotton enhanced with embroidered panels of natural silk, yet the embroidery is so subtle and intricate that to appreciate its beauty fully requires concentrated attention. The selection of a creamy silk for the embroidery of this white cloth suggests the desire for a subtle garment where modulation of texture and color is achieved through an eyelet-stitch technique that results in a denser surface and a slightly deeper cream tone. This type of riga, rather than the bolder and more colorful garments commonly found in local markets, is the kind of gown favored by Hausa men for important religious and social occasions.36

A particularly fine example of the combination of the sculptor’s innate sensitivity to material with the organizing possibilities and patterns of geometry may be witnessed in a Dogon stool from the Republic of Mali (fig. 11). Among the Dogon, highly figurated stools are invariably associated with men of substance, elders and leaders known as hogons, who guide the life of village communities. Such stools have a round seat supported by generously sculpted caryatid figures that rest upon a circular base, and they are marvels of concentrated artistry. Regarded as objects of prestige, they are not sat upon but maintained as sculpted signs of authority, vested in living leaders by lineage ancestors from the past. This Dogon stool, however, is different in every conceivable way—its overall shape, its obvious evidence of use, and in the fact that it eschews the traditional Dogon love for intense sculptural figuration in favor of surface carving and embellishment that is both intricate and subtle. The example is wholly influenced by the patterns and geometric precision of Islam, for the seat itself and the sides of the stool have been generously pierced, allowing for the play of light upon the chevron, triangular, interlace and five-square patterns that dominate this graceful object. In this Dogon stool, the sculptor has reshaped form into delightfully complex Muslim patterns and configurations.

Fig. 9. The registered logo for Flying Horse Blankets produced by Mantex Manufacturing in Kano, Nigeria with the image of a smiling al-Buraq in flight.

Fig. 10. A lavishly embroidered Hausa man’s gown (riga). Eyelet stitching enhances the richness of the embroidery and dramatically reveals the chest panel containing a square of five circles across and five down. Metropolitan Museum of Art, #31979.206.279.

Fig. 11. This Dogon stool is influenced by the patterns and geometric precision of Islamic design. Its seat and the sides of the stool have been pierced and cut through to allow for the play of light upon the chevron, interlace and five square patterns. American Museum of Natural History. #90.2.3539.

To spend time in an African Muslim community is to become acutely aware that one has entered a very distinct environment, one that is qualitatively different from a traditional or Christian setting. There are, of course, the obvious differences, certain sights and sounds that are immediately recognizable as Islamic: the mosque, the manner of dress, and the call to prayer that punctuate daily life. Another feature that impresses itself almost as quickly upon the visitor is the very private nature of family life, a factor that has inspired styles of Muslim domestic architecture found everywhere on the continent. Such architecture is remarkably consistent, especially in urban settings, as it is oriented not toward the outside world, but toward a set of interior spaces and courtyards within which life is conducted. Houses consist of solid and thick walls, and in Timbuktu and other towns along the Niger Bend, for example, one encounters single- and double-storied rectangular mud-brick homes with fortress-like walls that are buttressed at regular intervals. What impresses the viewer are these unrelenting slabs of mud brick that shut out the world and hide the life contained within them. Only an occasional wooden door, often embossed and studded with finely forged geometric iron shapes and knockers, announces the presence of a home. Such doors, and a few small openings at the second-story level filled with shuttered and grilled windows, are all that relieve the monotony of these mud walls and allow light and sound to penetrate.

Nothing illustrates the special character of Muslim domestic architecture quite as dramatically as Swahili towns on the east coast of Africa. These towns, born out of the interchange between coastal peoples with Muslim Arab, Persian, and, later in history, Indian or Malabar merchants, have a distinctive style, radiating a special character that is the result of a felicitous blending of Islam and African elements over the last ten centuries.37 The Swahili were and are primarily townspeople, although never exclusively so, and it is only within the urban setting that one can truly appreciate the full flowering of Swahili civilization. The urban and urbane are in fact inseparable from the very definition of being Swahili, for as James de Vere Allen tells us, the Swahili themselves stress that culture can flourish only in towns, and is indeed the “prerogative of townsmen.” To the Swahili, “culture is interpreted as a social patina, a way of life and knowledge of how to behave that can only be learned, indeed can only be practiced, by those living in towns.”38 The most visible expression of Swahili identity and culture is surely its stone houses, enhanced with coral-rag and stucco plasterwork and richly carved doors, created with a sense of style and a desire for privacy that is stunning.

Stone houses have been a feature of this coastal civilization since at least the thirteenth century, attesting to the prosperity enjoyed by various Swahili communities stretching from Mogadishu in Somalia to the southern coast of Tanzania. These homes, so utterly different from the wattle-and-daub mud houses of non-Swahili neighbors, dominate the townscapes of the coast and have always been an index of the heightened status enjoyed by their occupants. Grandly conceived, and constructed out of permanent materials, such houses (often two-storied) effectively wall off prosperous Swahili families from commoners and encourage a lifestyle imbued with a special urban elegance.39 Public spaces and guest rooms are always located just inside the entrance of such homes, while more private spaces are situated beyond the generous courtyard and toward the back of the house. Special attention has always been paid to the rooms of the harem, insuring their seclusion from the courtyard, and creating a space for the women that is sumptuously decorated. Whole walls of the harem consist of elegantly carved and plastered niches that contain everything from imported glassware to exotic ceramics and brass items. Two-story houses enable the wealthiest Swahili families to accommodate housing for a suitable number of servants, while still ensuring the family a sufficient degree of privacy. In their grandeur and spaciousness Swahili stone houses have been not only perfectly designed for daily living but also to accommodate the most important of social events—births, marriages, and even the funerals of family members all within the confines of its shielding walls.

Having begun this excursion into the artistry and character of belief with a discussion of the importance of individual prayer and the believer’s passion for the words of God, it seems only fitting to conclude with a look at Muslims praying together at the mosque, surely the most important religious institution and building within Islam. The word for mosque is masjid, and in Arabic it simply means “a place of prostration” before God. Thus a patch of ground covered by a mat, such as the marvelous Swahili mswala described earlier, fully qualifies as a masjid so long as the believer using it inclines himself before God with a pure heart. Indeed this mswala (the word literally means “a place of prayer”) captures the very essence of the word as it appears in the Quran, for nowhere in this book of revelations does the word masjid specifically refer to a religious structure but simply to any place where God is worshipped. Anyone who has traveled among Muslims in Africa quickly realizes that a masjid may be the humblest of religious precincts. In rural Côte d’Ivoire, it was, and perhaps still is, not uncommon to find places of prayer whose perimeters were carefully marked with a group of stones or by inverted green bottles wedged into the ground. What was critical, as is the case with even the grandest mosques, was that each place of prayer be carefully aligned toward Mecca.

The root meaning of the word masjid immediately alerts us to other aspects of Muslim worship that need to be appreciated. Islam, among all the universalistic religions of the world, distinguishes itself by its structural and formal simplicity:

There is no priesthood, no bewildering incantation, no solemn music, no curtained mysteries, no garments for sacred wear contrasted with those of the street and marketplace. All proceeds within a congregational unison in which the imam, or leader, does no more than occupy the space before the niche and set the time for the sequence of movements in which all participate.40

A Muslim service is remarkably direct, its flow utterly different from the intensely ceremonial liturgies found in most other great religious traditions. Prayer within Islam is essentially a solitary act, except for the Friday noon service, when Muslims congregate at the main mosque of their community, the masjid al-jami, or Friday mosque, to pray together and hear a sermon delivered by the imam or other notable. Although this is usually a short service, lasting less than an hour, what impresses the observer most forcibly is the sense of religious solidarity forged by the prayers, bowings, and homily. People are well dressed, most often in sparkling white clothing, and they form a chromatic community that sways, bends from side to side, and gracefully prostrates itself to the sounds of prayers and chanting. All the worshippers face the Mihrab niche, face east toward Mecca with a common purpose, a shared heart and mind, and this unity forged within the walls of the masjid al-jami is unforgettable.

Mosques in Africa, whether modest neighborhood buildings or impressive masjid al-jami, are all fundamentally places of prostration, religious spaces within which believers converse intimately with God. The mosque as a built environment is religious architecture that fully honors the ancient definition of the word masjid, a place dedicated to those who incline themselves before Allah. As such, a mosque does not require large processional spaces; it does not need to set aside room for a choir, or elevate portions of its interior for a hierarchy of religious officials. Its architectural requirements are remarkably minimal, a fact about the mosque that has been noted by Kenneth Cragg:

It is essentially an essay in religious space: by definition it is a place for prostration. Hence the carpets (or more commonly in Africa, finely woven mats) and the unencumbered expanses of area, whether domed or pillared. The niche, or mihrab, is not a sanctuary. It is merely a mark of direction, a sign of the radius of the circle of which Mecca is the center. Calligraphy, or script, and color, are the only decoration. … The mosque, it might be said, is the architectural service and counterpart of a devotion consistent with Islam.41

Decorative elements are kept to a minimum: the mihrab may be elaborated with glazed tiling or intricate stucco patterns; glass or brass lamps illumine the niche and the wide, rather than deep, areas reserved for worship; columns may be topped by exquisitely carved capitals as is the case in the main prayer hall of the mosque at Qayrawan in Tunisia but this is rather exceptional. The minbar or pulpit, placed to the right of the mihrab and found in all Friday mosques, can be impressive examples of Islamic woodworking and marquetry (the ivory inlaid minbar built for the late-fifteenth-century Mamluk Sultan Qaitbay and now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London is particularly splendid) but are typically little more than a raised platform of stone or mud-brick.42 Mosque interiors are an exercise in artistic restraint and discretion for anything that might distract the worshippers attention and concentration is conspicuously avoided.

Mosques do nonetheless, physically dominate any African Muslim community, as they do everywhere in the Islamic world, and they are the most visible sign of the strength of commitment to the faith. While it is still premature to contemplate an in-depth history of African mosques, the antiquity of this architectural form and some of the broad stylistic developments associated with this building can be reconstructed from archaeological evidence and descriptive accounts by early Muslim and later European travelers. For East Africa (see chapter 12 for a discussion of the early Islamic presence on the Swahili coast), archeological investigations by Mark Horton at Shanga and Chittick at Kilwa strongly confirm that mosques were being erected at the very beginnings of Muslim settlement.43

In Shanga, the earliest evidence of a mosque, a simple tent-like structure, has been dated by Horton to the late eighth century. As the community grew in size and strength, this rudimentary mosque was reworked (indeed, twenty-five times, according to Horton) until finally abandoned in the early fifteenth century.44 Building materials varied dramatically over time, from humble mud and mangrove beams to cut coral-and-lime plaster, suggesting not only a continual fluctuation in the fortunes of this early Swahili settlement but also how the members of Shanga constantly reinterpreted their most important religious structure. Horton’s data from Shanga are critical, for they not only present us with a dynamic history of the shaping and reshaping of this particular community mosque, but suggest a basic developmental sequence that might well apply to mosques from much of the Swahili coast.

Mosques also appear to have been constructed in the oldest Muslim communities in West Africa—creations of North African merchants involved in the trans-Saharan trade. Recent archeological work in southern Mauritania, in what is presumed to have been the Muslim sector of the town of Kumbi Saleh, capital of the empire of Ghana, have unearthed the tenth-century foundations of a stone mosque. According to Devisse and Diallo, this early mosque was enlarged in the following century and enhanced by tile work, with distinctive Islamic decorative motifs and Arabic script.45

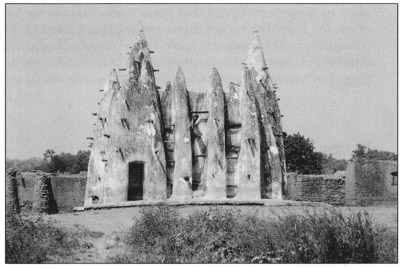

By the early fourteenth century, mosques built on a grand scale and in a distinctive Sudanese style (perhaps inspired by the Andalusian architect and poet al-Tuwayjin) were built within the empire of Mali at Gao, Timbuktu, and Jenne. This famous architect accompanied Mansa Musa on his trip home from the hajj in 1324 and is said to have worked extensively for the great ruler. According to Ibn Khaldun, al-Tuwayjin was apparently responsible for the construction of Mansa Musa’s domed palace, a wonderful structure whose walls were decorated with arabesques in the most dazzling colors. His patron, delighted with the results, rewarded him with gold dust valued at twelve thousand mithkal for this work.46

Fig. 12. A typical Mande mosque constructed of mudbrick and, in this instance, surfaced with a thin concrete wash. Photograph taken by the author in the Wala community of Nakore in northwestern Ghana, November 1967.

Although we will probably never be able to attribute the so-called Sudanese style to a single architectural genius like al-Tuwayjin with any degree of certainty, what can be said with confidence is that this distinctive mosque type was surely the product of talented Manding builders residing within the medieval empire of Mali.47

Building with the humblest of materials, sun-dried mud bricks mixed with straw, these early Manding masons and their successors created some of the most remarkable sculptural and architectural examples of mosque architecture found anywhere in the Muslim world (fig. 12). Constructed like fortresses, with battlemented walls and towers bristling with spikes, these mosques with gently sloping minarets have walls and buttresses pierced with projecting beams that serve as permanent scaffolding and help relieve their overall massiveness and horizontality. The interiors of such mosques present a different aspect, one of closeness and intimacy, for they are dominated by thick piers that support the roof, resulting in narrow aisles where congregants must place their prayer mats. Wherever the Muslim Manding settled, this mud-brick mosque architecture reappeared, a feature of their dispersion as distinctive as the language they speak. Mande mosques, like the other examples presented in this chapter, are vivid reminders that Islam and Africans have made something of each that is enduring—a testament to the artistry and character of belief.

Notes

1. See Heathcote 1977. This catalog includes a broad selection of Hausa artistry, ranging from leatherwork and gourd decoration to the arts of calligraphy and weaving. A modest catalog, it remains our basic source for the arts of this important culture.

2. See especially Wilks’s monumental study of the Asante state (Wilks 1975). For the influence of Islam upon Asante regalia, see Bravmann and Silverman 1987.

3. Adahl 1995.

4. Ibid., 10.

5. Ibid., 17.

6. I want to thank Professors Karin Adahl and Berit Sahlstrom and the Research Group for African and Islamic art at Uppsala University for the opportunity to present my paper “Islamic Spirits and African Artistry in Trans-Saharan Perspective” to a discerning audience. This conference allowed me to share some preliminary thoughts on Sudanic aesthetic elements in Black Moroccan creativity and the artistic interface between North Africa, the Sahara, and Sudan.

7. Geertz 1971, 14–15.

8. Picton 1995.

9. Abiodun, Drewal, and Pemberton 1994.

10. Picton 1995, 87–89.

11. Gbadamosi 1978.

12. Brenner 1984. Brenner’s biography of this Fulani cleric is a model study that thoroughly traces the spiritual path followed by Cerno Bokar.

13. Gibbal 1994, esp. chapter 8.

14. Brett-Smith 1994, 21.

15. Ibid., 20.

16. These include a number of eye-opening publications by Labelle Prussin on various aspects of African Islamic architecture and design, especially her 1986 volume. Mark’s sensitive analysis of Muslim elements found in Cassamance masking and initiation ceremonies is discussed in Mark 1992. Our knowledge of Akan metalworking has been enlarged by Silverman’s (1983) careful examination of North African metal basins and their impact upon the Akan. Lamp 1996 provides a thoughtful study of Baga cultural and artistic life in the face of Muslim reformist movements in contemporary Guinea.

17. Trimingham, 1959.

18. Geertz 1976, 1494.

19. Bravmann 1983, 19.

20. Stuhlmann 1910.

21. Bravmann 1983, 20.

22. Ibid., 25.

23. Ibid., 29.

24. Doutte 1908, 150–51.

25. Bravmann 1983, 44.

26. These phrases have been borrowed from Hiskett 1973, esp. chapter 6.

27. Information regarding the gifting of this drum to the British Museum was kindly supplied by Nigel Barley.

28. Bravmann 1995.

29. Samkange 1971, 410.

30. Picton and Mack 1979, 171.

31. The Gnawa of Marrakesh are descendants of Sudanese slaves and form a small but rather distinct community within Marrakesh. They are known as master healers of people struck by or possessed by the jinn, and their possession ceremonies (derdeba) are a marvelous blending of Sudanic expressive modes with elements derived from North African sufism.

32. Arberry 1955, sura 2, verse 183, p. 53.

33. Bravmann 1983, 68.

34. I want to acknowledge my debt to Diana de Treville for bringing this print of al-Buraq to my attention and for making available to me her translation (June 8, 1974) of its inscriptions.

35. I am indebted to John Lavers for the advertising label of this whimsical example of al-Buraq.

36. A fuller discussion of this handsome riga can be found in Bravmann 1983, chapter 6.

37. Middleton 1992 provides a superb study of this complex and sophisticated civilization.

38. Allen 1974, 134.

39. Middleton 1992, 63–68.

40. Cragg 1974, 56.

41. Ibid., 59.

42. Contadini 1995.

43. Horton 1996; Chittick 1974.

44. Horton 1996, chapters 9 and 10.

45. Devisse and Diallo 1993, 103 ff.

46. Ibn Khaldun, Kitab al-’Ibar, in Levtzion and Hopkins 1981, 335.

47. Prussin 1986, esp. chapter 6.

Bibliography

Abiodun, R., H. Drewel, and J. Pemberton. 1994. The Yoruba Artist. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

Adahl, K. 1995. “Islamic Art in Sub-Saharan Africa: Towards a Definition.” In Adahl and Sahlstrom 1995.

Adahl, K., and B. Sahlstrom. 1995. Islamic Art and Culture in Sub-Saharan Africa. Uppsala: Acta Universitatsis.

Allen, J. de Vere. 1974. “Swahili Culture Reconsidered,” Azania 9:105–38.

Arberry, A. J. 1955. The Koran Interpreted. New York: Macmillan.

Bravmann, R. A. 1983. African Islam. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

———. 1995. “Slit Drum.” In Phillips 1995, 133.

Bravmann, R. A., and R. A. Silverman. 1987. “Painted Incantations: The Closeness of Allah and Kings in 19th-Century Asante.” In The Golden Stool: Center and Periphery, ed. E. Schildkrout. New York: American Museum of Natural History.

Brenner, L. 1984. West African Sufi. Berkeley: Univerisity of California Press.

Brett-Smith, S. C. 1994. The Making of Bamana Sculpture. New York: Cambridge Univeristy Press.

Chittick, H. N. 1974. Kilwa, an Islamic Trading City on the East African Coast. Nairobi: British Institution in Eastern Africa.

Contadini, A. 1995. “Minbar for the Sultan Qa’itbay.” In Phillips 1995, 595.

Cragg, K. 1974. The House of Islam. Belmont: Dickenson.

Devisse, J., ed. 1993. Valles du Niger. Paris: Editions de la Reunion des Musecs Nationaux.

Devisse, J., and B. Diallo. 1993. “Le Seuil de Wagadu.” In Vallées du Niger, ed. J. Devisse. Paris.

Doutte, E. 1908. Magie et Religion dans l’Afrique du Nord. Algiers: A. Jourdan.

Gbadamosi, T. G. O. 1978. The Growth of Islam among the Yoruba. London: Longman.

Geertz, C. 1971. Islam Observed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———. 1976. “Art as a Cultural System.” In Modern Language Notes, 91:1474–99

Gibbal, J. M. 1994. Genii of the River Niger. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Heathcote, D. 1977. The Arts of the Hausa. London: Commonwealth Institute.

Horton, M. 1996. Shanga, the Archaeology of a Muslim Trading Community on the Coast of East Africa. London: Cambridge University Press.

Hiskett, M. 1973. The Sword of Truth. New York: Oxford University Press.

Josephy Jr., A. M., ed. 1971. The Horizon History of Africa. New York: American Heritage.

Lamp, F. 1996. The Art of the Baga: A Drama of Cultural Reinvention. New York: Museum for African Art.

Levtzion, Nehemia, and J. F. P. Hopkins, eds. 1981. Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History. Trans. J. F. P. Hopkins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mark, P. 1992. The Wild Bull and the Sacred Forest. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Middleton, J. 1992. The World of the Swahili. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Phillips, T., ed. 1995. Africa: The Art of a Continent, 133 and 595. London: Royal Academy of Arts.

Picton, J. 1995. “Islam, Artifact, and Identity in South-western Nigeria.” In Islamic Art and Culture in Sub-Saharan Africa, ed. K. Adahl and B. Sahlstrom. Uppsala.

Picton, J., and J. Mack. 1979. African Textiles. London: British Museums.

Prussin, L. 1986. Hatumere: Islamic Design in West Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Samkange, S. 1971. “Wars of Resistance,” In The Horizon History of Africa, ed. A. M. Josephy Jr.

Silverman, R. A. 1983. “Akan Kuduo: Form and Function.” In Akan Transformations: Problems in Ghanaian Art History, ed. D. Ross and T. Garrard. Los Angeles: Museum of Cultural History.

Stuhlmann, F. 1910. Handwerk und Industries in Ostafrika. Hamburg: L. Friederichsen and Co.

Trimingham, J. S. 1959. Islam in West Africa. Oxford: Claredon Press.

Wilks, I. 1975. Asante in the Nineteenth Century. London: Cambridge University Press.