CHAPTER ONE

The Birth of the United States Navy

The First Warships with Missouri Names—St. Louis and Missouri

In 1781, General George Washington wrote to his friend the French Count Lafayette: “It follows . . . as certain as night succeeds the day, that without a decisive naval force we can do nothing definitive—and with it everything honorable and glorious.”

Many Americans, including Washington himself, were skilled, experienced soldiers who had fought alongside the British and felt confident against them. But by the time of the Revolution, Britain had perfected sail-powered wooden ships. The powerful British navy had fleets of battleships along with smaller, faster frigates and sloops that served as scouts and also acted as cruisers, protecting British commerce and attacking enemy vessels. The rebels could not hope to build a navy able to compete. They could, however, adopt guerrilla tactics to harass and plague their powerful enemy. Americans built or hired small, fast warships and put in command aggressive sailors such as John Paul Jones to attack British merchant ships. In 1778 America also sent Ben Franklin to negotiate a treaty with England’s bitter rival, France, and it was a French fleet that supported General Washington and allowed him to cut off and capture a British army at Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781 and win American independence.

Even as Americans began to enjoy their new freedom they discovered the costs and burdens of liberty. Americans were suspicious of professional warriors and reluctant to pay to maintain a permanent navy, but they did want to trade with the whole world. Thomas Jefferson defined the role of the U.S. Navy for the next hundred years by arguing for a small number of modest warships to protect American commercial rights, and discourage powerful European enemies by threatening their own merchant ships. He believed the new United States was too weak to challenge the great European powers and should seek peaceful cooperation rather than confrontation. Not until the early twentieth century would the United States build a navy to match those of the leading world powers.

Still, the United States quickly became a trading powerhouse, with booming seaports. By 1820 only England had more trade with China than the United States, and the U.S. Navy had frigates and smaller warships all over the world whose captains made commercial treaties with local rulers, cooperated with the British navy, and acted as “policemen” to protect American rights, lives, and property.

In 1827, six years after Missouri joined the Union, the navy began building a twenty-gun sloop of war at the Washington Navy Yard. Measuring 127 feet long, weighing 700 tons, carrying a crew of 125 officers and men, and costing $125,000, this modest ship was perfectly suited to the duties of the American navy and to the modest role America then played in the world. One of eleven “sister ships” and named St. Louis, she was to serve all over the world and even to play the central role in a celebrated diplomatic crisis with a European empire.

Driven by the wind, the sloop could cruise for months at a time, stopping only for water and food for her crew. Two years after work had begun on her, St. Louis sailed under Commander John D. Sloat, leaving the naval base at Hampton Roads on Chesapeake Bay February 1829 on her way to join the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Squadron. She sailed around stormy Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America, arriving in Peru in June.

St. Louis patrolled the Pacific coast of South America for the next two years as Spanish colonies struggled to gain independence. American sailors were often caught between Latin American revolutionaries and Spanish authorities, with both sides sending out raiding ships, declaring blockades, and harassing neutral merchants and sailors. St. Louis escorted American merchant ships; her captain interceded with local officials on behalf of Americans; and her crew guarded the cash earned by American merchants. In spite of America’s natural sympathy for the “Great Liberator,” Simón Bolívar, and other revolutionary heroes fighting European domination, the navy tried to remain neutral unless American citizens were threatened. Unfortunately, Commander Sloat soon found himself and St. Louis caught up in Peruvian politics. Before today’s instant, worldwide communication, American naval officers often had to rely on their common sense, the force of their guns, and vague written instructions laying out American foreign policy.

In the spring of 1831, Peruvian President Augustín Gamarra thought that his “notoriously unreliable” vice president, one General La Fuente, was planning to overthrow him and sent soldiers to his house to kill him. La Fuente’s wife held the soldiers at bay while he fled in his nightshirt. At five in the morning he arrived by canoe at the St. Louis. Commander Sloat gave him “asylum against the mob,” and the commodore of the Pacific Squadron wrote the American diplomatic representative in the Peruvian capital, Lima, praising Sloat’s conduct as “honorable, benevolent, and discreet.”

Commander Sloat then found himself stuck with the “unreliable” general for almost a month and was forced to ask the secretary of the navy to reimburse him for almost one thousand dollars “spent on entertaining” his guest. Because the navy had no funds for such activities, President Andrew Jackson had to ask Congress to appropriate the money.

St. Louis next sailed to Pensacola, Florida, in October 1832, under Commander John T. Newton. Ten years later, Newton, by then a captain, would command the first Missouri as she steamed across the Atlantic carrying U.S. Commissioner to China Caleb Cushing. Newton and St. Louis joined the West Indies Squadron, and until 1838 the ship patrolled the Caribbean, encouraging trade, suppressing piracy and the slave trade, and protecting American commercial rights.

After repairs at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, St. Louis again sailed in June 1839 to join the Pacific Squadron off California, becoming the first U.S. Navy ship to visit the port of San Francisco in Mexican California. While off California, St. Louis became involved in tensions between Mexican governors and American and British settlers. The number of settlers was growing, and fearing that they were plotting to overthrow him, California governor Juan Bautista Alvarado ordered forty-eight Americans and Britons arrested. After protests by St. Louis’s commander, French Forrest, and the British consul, Alvarado set the prisoners free.

By the spring of 1843, St. Louis had returned to the East Coast. She was dispatched from Norfolk, Virginia, to join the East Indies Squadron. On that trip, she sailed around the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa and through the Indian Ocean. China and the Indonesian Islands were rich sources of trade for Europeans and Americans, and St. Louis was part of the force sent to suppress Indonesian piracy and assure that American merchants received their share of the Chinese market.

In the 1830s the British had dominated trade with the decaying Chinese empire. By 1842 the U.S. Navy was pursuing American commercial interests, and Captain Lawrence Kearny was visiting Chinese ports, seeking treaties to allow American merchants and ships the same rights enjoyed by the British. To finish the work begun by Kearny, the United States decided to send a representative to negotiate a formal treaty with China. To transport this minister, Caleb Cushing, the navy chose its most modern ship, the steam frigate Missouri.

The navy’s first two oceangoing steam frigates were named for America’s great rivers: the Mississippi and the Missouri. American and European inventors had been experimenting with steam power for decades, but early steamships were not very practical for war because their giant side paddle wheels limited the number of guns they could carry. The fragile paddle wheels were also vulnerable to enemy fire, and on long voyages, the engines burned more coal than the ships could carry. A steamer with its paddle wheels shot to pieces was worse off than an old-fashioned sailing ship, and steam only showed its clear advantages over sail once practical underwater screw propellers were invented. By the time Congress directed the navy to build the two “sea steamers” in March 1839, the British and French navies already had over a dozen steamers each in their fleets. Missouri and Mississippi were the first American warships in which machinery and coal successfully replaced the sails and wind that had moved ships for thousands of years.

The sister ships were built under the active supervision of one of the navy’s finest officers, Matthew Calbraith Perry, brother of Oliver Hazard Perry, the hero of the Battle of Lake Erie in the War of 1812. In 1853, Matthew Perry would lead the first expedition to open Japan to American trade, using Mississippi as his flagship. When launched at the New York Navy Yard in 1841, the ships were the largest in the U.S. Navy—each was 229 feet long, weighed 1,700 tons, and carried crews of 226 men. Each had cost $570,000 and was armed with 10 guns. Still, aside from their engines, paddle wheels, and smokestacks, they were traditional wooden ships with masts and sails and would not have seemed out of place in the Revolutionary War. The navy was very pleased with the performance of the new ships, although the one test between them, a race from New York up the Potomac to the Washington Navy Yard in the spring of 1842, ended with Missouri running aground at Port Tobacco, Maryland, just south of Washington, on April 1, and the engines of Mississippi overheating. The ships consumed huge amounts of coal, but they had been designed to carry enough fuel to steam for twenty days.

In early 1842, Missouri conducted trials out of Washington, and the proud navy showed off its advanced new ship to thousands of visitors. After a cruise to the Gulf of Mexico, she returned to Washington to take aboard Commissioner Cushing for his trip to China. Cushing carried his large library of books on diplomacy and China, letters from President John Tyler to the emperor of China, and instructions from Secretary of State Daniel Webster that “a leading object of the mission. . . is to secure the entry of the American ships into [Chinese] ports on terms as favorable as those [of] British merchants.” He also packed a fine uniform: a blue coat with gilt buttons, white pantaloons with a gold stripe, and a “chapeau with a white plume.” On August 6, 1843, President Tyler visited Missouri and watched the crew in action as the two huge paddle wheels smoothly propelled the ships “with noiseless accuracy” around Hampton Roads near Norfolk, Virginia. Missouri then left for Europe, carrying Cushing on his way to China. During sea trials and contests with her sister, Mississippi, Missouri had shown that her engines could drive her as fast as sixteen miles per hour, and in the next twelve days she proved she could steam across the Atlantic, her engines pushing her almost nonstop day and night.

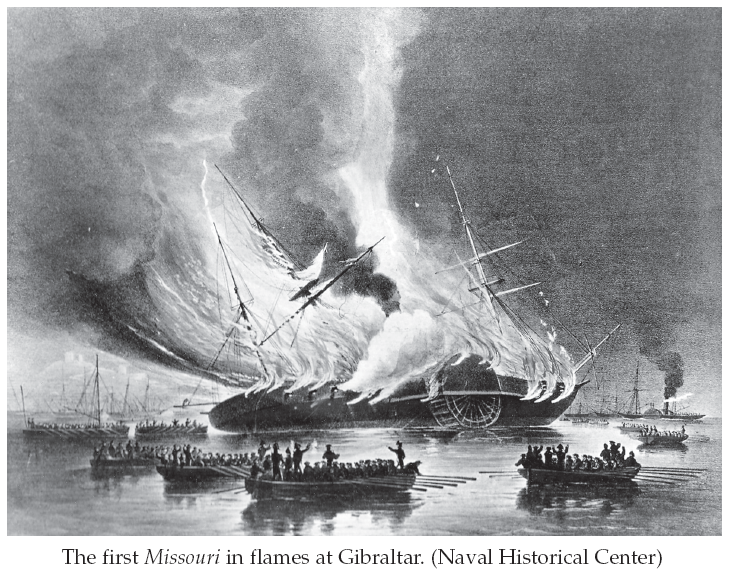

Missouri arrived at the British naval base of Gibraltar, at the mouth of the Mediterranean Sea, on August 25 and saluted the British fortress and warships anchored under the famous Rock of Gibraltar. The next day, as the crew began loading coal and water and overhauling the steam engines, Captain John Newton and Commissioner Cushing went ashore to greet the American consul and British governor Sir Robert T. Wilson. That evening Captain Newton’s visit was interrupted by word of fire aboard Missouri, and he rushed back with Governor Wilson and British Admiral Sir George Sartorius of the British battleship Malabar to try to save his ship. As Newton wrote in his report to the navy, he found “flames raging with violence, and the officers and crew exerting themselves to their utmost to overcome them.” Despite the best efforts of the American crew and British sailors from Malabar and from Gibraltar, pumps and water buckets were no match for the fire, which was fanned by high winds. Newton flooded Missouri’s gunpowder magazines to prevent explosion; then, just before midnight, he abandoned ship, escaping down a rope to a waiting boat. At three in the morning the guns and magazine exploded, and the ship settled to the shallow bottom of the harbor.

Over a hundred years later, as another Missouri steamed toward Gibraltar in March 1946, the American consul at Gibraltar, C. Paul Fletcher, wrote a letter to Secretary of State James Byrnes in which he described a picture on the consulate wall showing “the falling of the [Missouri’s] mainmast, and explosion of the last gun, which occurred at the same moment. . . . On the spanker-boom is an unfortunate Bear which perished in the flames.”

Aside from the “unfortunate Bear,” a pet, Cushing lost his books and grand uniform, and the crew lost everything but the clothes they were wearing. While the battleship Malabar took in his crew, Newton had the unhappy task of reporting the loss of his ship to the navy. In his report on “the destruction of our noble ship,” Newton said that despite “the sad and melancholy scene, I am happy to bear testimony to the zeal and firmness of all the officers [who were] honorable to themselves and to the service. The crew also did their duty like men, and deserve well of their country.”

Included in his report is the testimony of three crewmen. One “coal heaver,” John Sutton, went to a storeroom to get a scale to weigh coal. As he pulled the scale off a shelf, a wrench fell, too, breaking a glass container of turpentine. Sailors William J. Williams and Alfred Clam were working on the engine, and Clam’s lamp ignited the dripping turpentine. They were unable to stop the fire before the flames reached the wooden hull and doomed the ship.

The U.S. Navy was not to have another Missouri for sixty years, but Mississippi had a long and distinguished career, serving in the Mexican War and in the Civil War, both as part of the Union blockade and as one of the biggest and most powerful ships in Admiral David Farragut’s fleet that attacked and captured New Orleans. While she had been built for ocean sailing, she spent her last days on the river for which she was named.

Less than two years after the British had come to the aid of the burning Missouri at Gibraltar, the sailors of St. Louis were able to help endangered British citizens in New Zealand. As St. Louis was returning to Norfolk from her China service, she stopped in March 1845 at the small British settlement of Russell in New Zealand. Commander Isaac McKeever learned that a native Maori chief, Honi Heke, was threatening to attack the settlement because of British violations of treaties and broken promises to respect Maori lands. Because the British had only a few soldiers and one small warship to defend the settlers, Commander McKeever met with Honi Heke and received his “pledge of safety to the innocent women and children of the Europeans” and a promise to respect American property. McKeever then offered frightened settlers safety aboard St. Louis, and when Honi Heke attacked and destroyed the British fort, McKeever saved the fleeing garrison. He refused British pleas to land armed sailors to “save the day,” insisting on American neutrality, but he did lead unarmed boats ashore under Maori fire to rescue civilians. As the Maoris burned everything except the Catholic mission and the American warehouses, St. Louis and two British ships rescued all the European settlers. Echoing American gratitude at Gibraltar, British Governor Robert Fitz Roy praised McKeever and his crew, saying “he sent his unarmed boats and went himself under frequent fire to [rescue] the women and children and convey them safely to his [ship].”

McKeever then returned his ship to Norfolk, where St. Louis spent the next three years out of service. In 1848 she joined the South American Squadron off Brazil just as Europe was being overwhelmed by a new wave of democratic and nationalistic uprisings and revolutions. Germany and the Austrian Empire were especially shaken by uprisings among minority nationalities, but the imperial army remained loyal and managed to suppress the revolutionaries. Many of these defeated revolutionaries, like millions of oppressed or unhappy people before and since, came to the United States. Called “Forty-Eighters,” these new immigrants included Carl Schurz, later a Union general, senator from Missouri, and secretary of the interior, and two Hungarian patriots named Lajos Kossuth and Martin Koszta.

While many exiles came to the United States, others fled to havens closer to Europe, including Turkey and other parts of the crumbling Ottoman Empire. The Muslim Turks and Christian Austrians had been enemies for hundreds of years, and much of modern Yugoslavia and the Balkans remained Ottoman. Enemies of the Austrian Empire found a haven there, as they did in America. Kossuth came to the United States in December 1851 aboard the Mississippi at the invitation of Congress, and during his tour received an enthusiastic welcome in St. Louis where many Forty-Eighters had settled. Citizens of St. Louis urged Congress to give land to the Hungarian refugees, and Missourians named a town for Kossuth. His follower Martin Koszta had already immigrated and was working in New York City. In July 1852 Koszta declared his intention to become an American citizen.

Before he earned his citizenship, however, his employer sent him to Smyrna, Turkey, on business. There, he visited American consul Edward S. Offley, who cautioned him that because he was not yet a citizen, the consul could only “grant him . . . unofficial influence in case. . . of difficulties.” Koszta nevertheless remained in Smyrna, where Austrian agents looking for “dangerous” revolutionaries spotted him. On June 22, 1853, he was kidnapped by the Austrians and dragged aboard the Austrian warship Hussar in chains. Exiles from Hungary, Italy, and other countries, as well as local American and British businessmen immediately protested to the American consul and the Turkish authorities, but they were powerless to rescue Koszta.

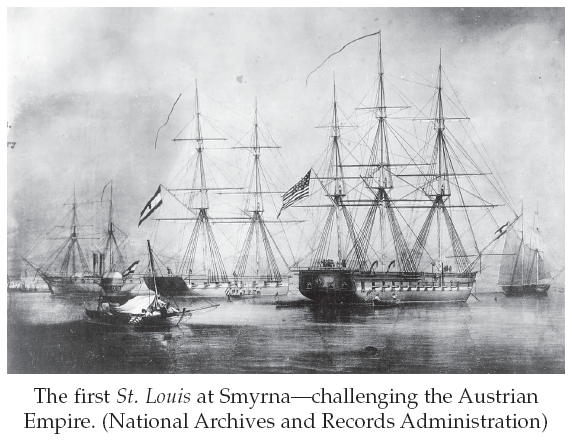

The next day, with Smyrna in an uproar over the kidnapping, an American warship arrived in the harbor. St. Louis had finished her service off South America, and in August 1852 had been assigned to the Mediterranean Squadron. Now commanded by Commander Duncan N. Ingraham of Charleston, South Carolina, she was about to play a central role in a major international crisis.

Koszta’s outraged supporters immediately appealed to Commander Ingraham for help, and he and consul Offley visited Hussar, where they found Koszta in chains. Ingraham demanded that the chains be removed, and he and the consul consulted by letter with the American minister in the Ottoman capital of Constantinople. All were aware that Koszta was not yet an American citizen; the Austrians considered him an Austrian subject. Local passions remained high. A mob attacked and murdered one of Hussar’s officers. At this point, an American congressman, Caleb Lyon of New York, arrived, and urged Ingraham “Do not let this chance slip to acquit yourself nobly and do honor to our country. . . .The eyes of nations are upon the little St. Louis and her commander.” Ingraham also received an encouraging if vague letter from the American minister. He then returned to Hussar and formally asked Koszta: “Do you demand the protection of the American flag?” When Koszta said yes, Ingraham responded: “Then you shall have it.”

On July 2, 1853, Commander Ingraham delivered an ultimatum to Captain August von Schwarz of Hussar: “[I] demand the person of Martin Koszta, a citizen of the United States . . . and if [refused, I will] take him by force.” In spite of heavy odds against him, he then prepared St. Louis for battle against Hussar and two smaller Austrian warships. St. Louis midshipman Ralph Chandler, later an admiral, recorded in his diary: “every man on board seemed anxious for a fight. . . . We were all in a great state of excitement, but not an expression of fear or regret did I hear.”

As Ingraham loaded his cannon, consul Offley warned the Austrian consul-general: “Ingraham is determined to go to the finish, and he is a professional fighting man. . . . Do you desire bloodshed?” Ten minutes before Ingraham’s ultimatum expired, the Austrian consul-general ordered Captain von Schwarz to release his prisoner; Koszta was sent ashore into the custody of the local French consul.

In his report to the secretary of the navy, Commander Ingraham wrote:

I have taken a fearful responsibility upon me by this act; but . . . could I have looked the American people in the face again if I had allowed [Koszta] to be executed and not use the power in my hands to protect him for fear of doing too much?

. . . I . . . feel I have done my best to support the honor of the flag, and not allowed a citizen to be oppressed who claimed at my hand the protection of the flag.

He also wrote the American minister to Turkey: “and now you gentlemen of the pen must uphold my act . . . as [the Austrians] had more guns than I had . . . and three [ships] to help them, they will not like to own it was fear that made them deliver up Koszta.”

Smyrna celebrated the rescue of Koszta with a great party for Commander Ingraham and his officers, with the “popping of bottle corks instead of the big guns,” and the local orchestra came out to St. Louis on a barge to serenade the crew. Ironically, two days after St. Louis and the Austrian ships had almost fought a bloody battle, Hussar and her two Austrian sisters flew the Stars and Stripes from their masts in honor of American Independence Day.

As with other such “diplomatic” naval actions before transoceanic telegraph, the entire Koszta crisis was over before news reached Washington. Still, the actions of the American diplomats in Constantinople and Smyrna, and Commander Ingraham’s use of St. Louis to force an ancient and powerful European empire to back down, caused a sensation in Europe and America. Two weeks after the crisis, on Bastille Day, the French national holiday, a Paris newspaper joyfully declared: “everyone who has two free hands at the service of a noble heart will applaud with frenzy this grand example given by the new world to the old.”

After the fact, the American government also approved, and when Commander Ingraham returned to New York in September, he was showered with gifts and awards from Latin American and European exiles and patriots. He even received a costly naval chronometer from British working-men. In August 1854, Congress awarded him a gold medal and their “thanks. . . [for] his gallant and judicious conduct.” Martin Koszta also returned to the United States, married a widow in Chicago, and went bankrupt trying to ranch near San Antonio, Texas. He apparently died in Guatemala in 1858, fighting with Central American guerrillas. Ingraham was promoted to captain and appointed commodore of the American squadron in the Mediterranean. In December 1860 his home state of South Carolina seceded from the Union, and in February 1861 he resigned his commission to join the new Confederate navy. A few months later the entire Mediterranean Squadron was recalled to America to fight in the Civil War. Although Ingraham had been prepared to risk his life to rescue a Hungarian exile in the name of the American flag, he joined three hundred of his fellow naval officers in renouncing the Stars and Stripes to serve the Confederacy.

St. Louis had remained in the Mediterranean Squadron until 1855, when she was transferred to the coast of Africa to join the British navy in suppressing the slave trade. The U.S. had outlawed the trade in African slaves in 1808, but huge profits inspired many unscrupulous sailors to continue the illegal trafficking. In 1858 St. Louis joined the Home Squadron in the Caribbean until the outbreak of the Civil War.