CHAPTER TWO

The Civil War—Two American Navies

Another St. Louis and Another Missouri

Tension between the states over the issue of slavery had been growing even before slave-holding Missouri and free-state Maine joined the Union in the famous Missouri Compromise of 1821. Still, when southern states began seceding from the Union in December 1860, and Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed Florida Senator Stephen Mallory Secretary of the Navy of the Confederate States of America in February 1861, the U.S. Navy was poorly prepared for war. Many senior officers had begun their service in the War of 1812 and had last seen battle over a decade before, against the Mexicans in 1846–1848. The navy’s ships were small, old, and part of small squadrons scattered around the world. Almost half of the southern officers in the U.S. Navy resigned to fight for the Confederacy, including French Forrest, who had sailed St. Louis into San Francisco Bay in 1840, and Duncan Ingraham, who had rescued Martin Koszta from the Austrians in 1853. The Confederates also quickly captured navy shipyards at Norfolk, Virginia, and Pensacola, Florida, seizing hundreds of cannon and many naval supplies from these bases.

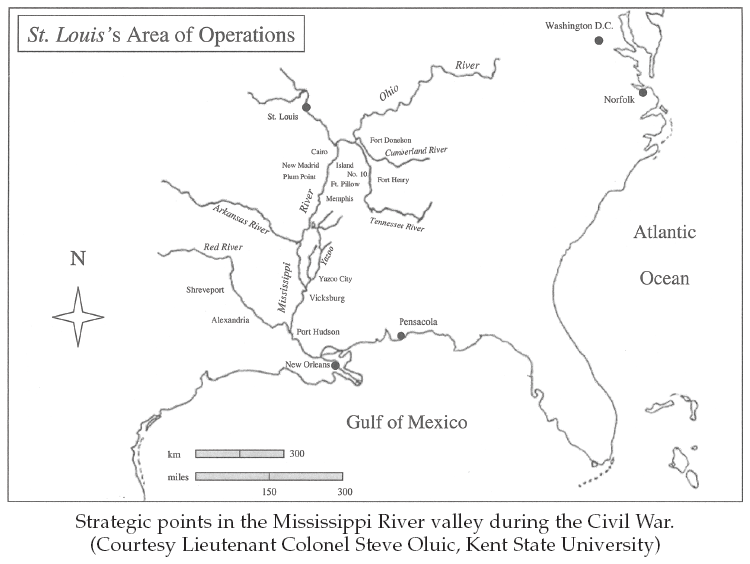

In spite of much early bungling, the Union entered the war with many advantages, including a much larger population and almost all the mines and factories needed to build the tools, weapons, and machines that this first modern technological war would demand. Finally, the Union had the benefit of a classic strategy: a blockade to cut the agricultural South off from foreign suppliers, and a plan to split and strangle the rebellion by capturing the rivers that divided the Confederacy. Thanks in large measure to powerful new unconventional ships built by a famous St. Louis riverman, the Union navy was able to seize crucial Southern strongholds along the Tennessee, Cumberland, Mississippi, and Red Rivers.

Before the Civil War, America had been content to lag behind Europe in many areas of military science and technology. Within five years, the Civil War had forced advancements in military and naval technology that made the Union navy for a brief time one of the largest and most powerful in the world. The South had no industry and few resources to build a modern armored steam navy. Confederate Secretary of the Navy Mallory relied upon the few tools at hand to build new types of weapons—ironclad warships, submarines, and explosive underwater mines (then called “torpedoes”). He also tried the classic American tactic of sending out fast commerce raiders like the Alabama and Shenandoah, captained by daring sailors like Raphael Semmes. Some two hundred Union merchant ships were taken during the war before the Federal navy captured or destroyed the raiders.

In January 1861, as state after southern state seceded from the Union, the sloop St. Louis was ordered to return from Vera Cruz, Mexico, to the Pensacola naval base. When Pensacola fell to the Rebels, St. Louis joined the navy ships enforcing the blockade. In September she helped the frigate Brooklyn capture the Confederate smuggler Macao off the Mississippi River. In February 1862, St. Louis was transferred to a new European Squadron. For the next two and a half years she patrolled the European and African coasts in search of Confederate commerce raiders. While St. Louis and her crew spent the Civil War on boring patrol, a second St. Louis would soon see more than her share of blood and death.

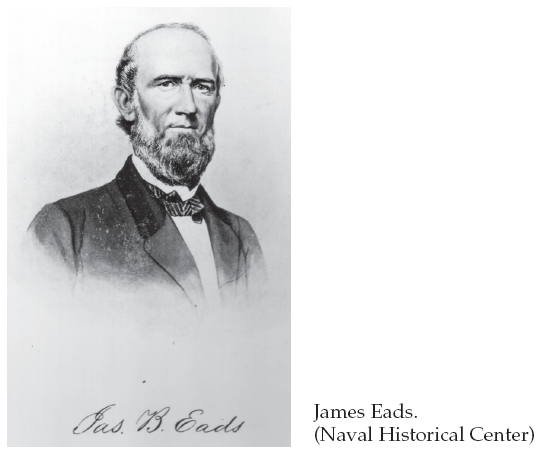

Many Missourians, including Governor Claiborne F. Jackson, supported the Confederacy, but Unionists controlled St. Louis. Among the strongest pro-Unionists was James B. Eads, who had made his fortune salvaging wrecked riverboats. He saw the strategic value of controlling the Mississippi, and well known for his enterprise and “hundred horsepower mouth,” he traveled to Washington in April 1861 to urge President Lincoln to establish a strong naval base at the junction of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers at Cairo, Illinois. U.S. army commander and Mexican War hero General Winfield Scott also favored an “Anaconda Plan” to strangle the south with a blockade and river campaign, and the famous U.S. Navy designer Samuel Pook quickly drew up plans for ironclad gunboats especially suited for river warfare. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles recommended that these boats be built by “western men. . . educated to the peculiar boat required for navigating rivers.” Eads was so eager to undertake the task that he agreed to build seven boats in only three months for ninety thousand dollars each, with a stiff penalty should he be late.

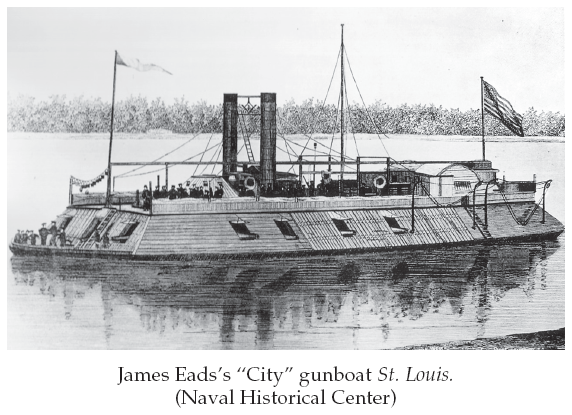

He began work at the Carondelet boatyard near St. Louis in August 1861 and soon had hundreds of Irish, French, and German craftsmen and twelve sawmills working around the clock. Although construction was delayed by lack of guns and the tardiness of the government in paying Eads, the gunboats were launched in the fall of 1861 and moved downriver to Cairo to receive their guns and crews. Christened St. Louis, Carondelet, Louisville, Pittsburg, Mound City, Cairo, and Cincinnati, the seven were known as “City” gunboats. Some 175 feet long and 50 feet wide, they were flat-bottomed, drew 7 feet of water, and had large center rear paddle wheels driven by coal-fueled steam engines. Each carried about a dozen guns and a crew of 175 officers and men. With a top speed of under nine miles an hour, they could sometimes barely move against a fast river current. Each engine burned some two thousand pounds of coal per hour and puffed loudly like railroad locomotives. Their chugging could be heard and their thick clouds of black coal smoke seen for miles up and down the river. The wooden ships’ gundecks and pilothouses were armored with iron backed by two feet of thick oak. They were painted black with red hulls, and different color stripes on the smokestacks identified the ships. St. Louis wore yellow stripes. Their sailors called the gunboats “turtles” or “Pook’s turtles” because they looked more like Mississippi mud turtles than ships or even riverboats.

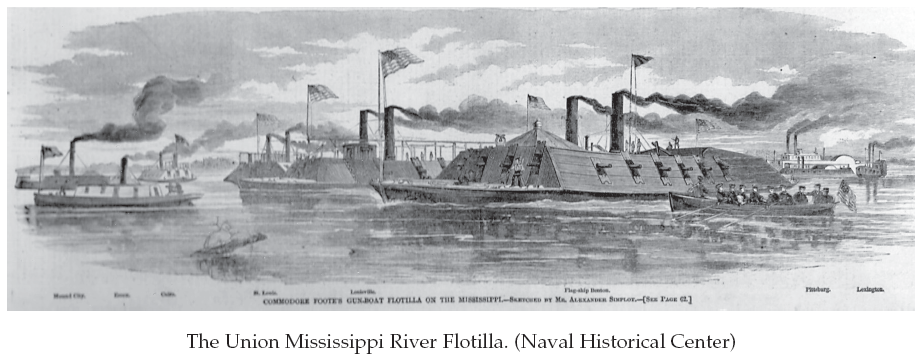

In January 1862 the gunboats were accepted by Gunboat Flotilla commander Captain Andrew Hull Foote, although he still lacked crewmen. It was difficult to find volunteers among western rivermen. The St. Louis Democrat of January 24, 1862, reported: “The pay of the sailor [$18 per month] is somewhat more liberal than that of the soldier, and his duties include no long marches or wet encampments. He gets his meals with unfailing regularity and has always a dry bed—luxuries which a soldier can seldom count on.”

Despite these advantages, Foote had to fill out his crews with untrained infantry and cavalry soldiers, landsmen, and even escaped or freed slaves. He warned his officers that soldiers “have hitherto led rather an irregular life, and had but few examples of well-disciplined people before their eyes. . . . Be strict. . . treat them kindly, but let them feel they must conform to naval laws.”

A month later Foote and the army commander in Cairo, Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, aggressively penetrated the heart of the Confederacy. From their Cairo base, Foote’s gunboats and Grant’s troops moved up the Ohio River to attack Fort Henry on the Tennessee River near the Kentucky-Tennessee border. On February 6, 1862, with sisters Cincinnati, Carondelet, and St. Louis leading the attack, Foote steamed slowly up to Fort Henry and bombarded the fortification for over an hour until Confederate General Lloyd Tilghman surrendered his troops. The new “brown water” navy thus captured a fortified rebel garrison with no help from ground troops. In the exchange of cannon fire, Foote’s flagship Cincinnati was hit thirty-one times but only suffered one sailor killed. St. Louis and Carondelet took more than a half-dozen hits each but suffered no casualties. In contrast, the converted riversteamer Essex was hit in the boiler, and the resulting explosion killed ten and wounded twenty-three.

Foote’s fleet adopted General Tilghman’s pet dog, “Ponto,” as spoils of this first victory. Ponto seemingly shifted allegiance and “left no doubt of [his] political [views.] If the sailors called him ‘Jeff Davis,’ Ponto would howl dolefully. If called ‘Abe Lincoln,’ he’d bark joyfully.”

Exploiting his first success, Foote pressed upriver, capturing Confederate steamboats and supplies and destroying railroad lines. Within a week, Foote and Grant attacked Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. Many rebel troops had escaped Fort Henry to reinforce Fort Donelson. The navy now learned the hard lesson that the Confederates had taught the Union army at Bull Run near Washington—this war would be a long, painful struggle. Foote led the gunboat attack on February 14 in St. Louis. Both St. Louis and Louisville were crippled by heavy fire, and Foote, along with many of his crew, was injured when a shell hit St. Louis’s wheelhouse. A cannon burst on Carondelet, and Pittsburg and other gunboats were also heavily damaged. Confederate cannonballs broke through iron plating, sending deadly wood splinters flying inside the boats. Other balls entered gunports, killing and wounding until the decks were slippery with blood. Although the boilers were padded with sandbags, some balls penetrated the boilers, scalding crewmen with steam. Battered and drifting, the fleet was forced to withdraw. The Union army then attacked; 500 Union soldiers were killed and 2,100 wounded. Although many rebels escaped, Major General Simon Buckner decided to surrender his 9,000 remaining troops and asked for terms. Grant replied that he would accept “no terms except unconditional and immediate surrender.” Buckner wrote back that “the overwhelming force under your command compel me, notwithstanding the brilliant success of the Confederate arms . . . to accept [your] ungenerous and unchivalrous terms.”

The Union navy had only fifty-four men killed or wounded, including Foote himself, but the fleet had been battered and had to withdraw to Cairo for repairs. St. Louis had been hit by fifty-nine cannonballs. Nevertheless, the Union now controlled the Tennessee and Cumberland River valleys and could quickly move gunboats and troops by water. Nashville soon fell to the Union.

An army of twenty-five thousand men under Union Brigadier General John Pope captured New Madrid, Missouri, in early March 1862, but the Mississippi was blocked by heavy Confederate fortifications on Island Number 10 in the middle of the river. Foote was suffering severe pain from his wound, but he moved his flotilla down from Cairo to support Pope’s army. On March 17, while St. Louis was bombarding the Confederate batteries on Island Number 10, one of her guns exploded, killing two and wounding ten of her crew. As a fellow captain complained, this was “another proof . . . that the guns furnished the Western Flotilla were less destructive of the enemy than to ourselves.” After two more weeks stalled by the guns on the island, Carondelet ran past the Confederate batteries during a thunderstorm on the night of April 4. Two nights later Pittsburg also braved the guns and joined her sister at New Madrid. Protected by these two ironclads, General Pope’s army crossed the river into Kentucky without losing a man. Surrounded, the Confederates on Island Number 10 surrendered five thousand soldiers and one hundred cannon.

Pope and Foote immediately pushed seventy-five miles farther downriver toward Memphis until they were again blocked by Fort Pillow on the Tennessee bluffs. There the advance stalled as Pope’s troops were diverted to support an attack on Corinth, Mississippi.

The navy was not idle though. At the mouth of the Mississippi, Flag Officer David G. Farragut commanded a fleet of big oceangoing warships, including the old Mississippi. In early April, Farragut moved his ships upriver toward New Orleans, dragging Mississippi over sandbars to reach deeper water. On April 18 his mortarboats under Captain David Dixon Porter began bombarding Forts Jackson and St. Phillip below New Orleans. On April 24 he steamed his fleet past the forts, and the next day Union troops reoccupied the Federal buildings in New Orleans and recaptured the city.

Two weeks later Flag Officer Foote, fearing that the pain of his wound was clouding his judgment, turned over command of his gunboat flotilla, sitting above Fort Pillow, to Captain Charles Henry Davis. Davis was shocked at the toll that the wound and war had taken on his friend, finding him “fallen off in flesh and depressed in spirits.” The next day, Sunday, May 10, the Confederate army’s “Mississippi River Defense Fleet,” eight rams clad in protective bales of cotton, surprised the Union fleet as it was lazily shelling Fort Pillow. The rebels were commanded by Captain James Montgomery and Missouri guerrilla General Jeff Thompson. Only one Union mortarboat was on duty, and her “escort,” Cincinnati, lay nearby with cold boilers and no power to move as her crew scrubbed her decks. Her sisters were too far upstream to help her as the rebel rams suddenly appeared around a bend in the river. Cincinnati was quickly rammed by three Confederate boats. Her guns did severe damage to the lightly protected Southern rams, but her captain was badly wounded and, with boilers and ammunition magazine flooded, she sank to the bottom. By now Carondelet and Mound City were coming to Cincinnati’s aid. Mound City was also rammed and ran aground to keep from sinking, but Carondelet and another Union ironclad chased the Southern rams back to the shelter of Fort Pillow’s guns. Cairo and St. Louis, moored across the river and blinded by morning haze, were never able to join the fight. The battle of Plum Run Bend was a real setback to the Union flotilla, caught by surprise and heavily damaged by the Southern rams. Montgomery bragged that the Union “will never penetrate farther down the Mississippi.”

Cincinnati and Mound City were raised from the river bottom and towed back to Cairo for repairs, and the Union flotilla sat above Fort Pillow waiting for Union rams to come downriver to match their enemy. On May 25 the seven steamers of Colonel Charles Ellet’s U.S. Army Mississippi Ram Fleet arrived, and Ellet urged Davis to attack Fort Pillow at once. The Confederate army withdrew from Corinth, however, and left Fort Pillow exposed. The garrison blew up the fort and escaped downriver on Montgomery’s defense fleet to make a stand at Memphis.

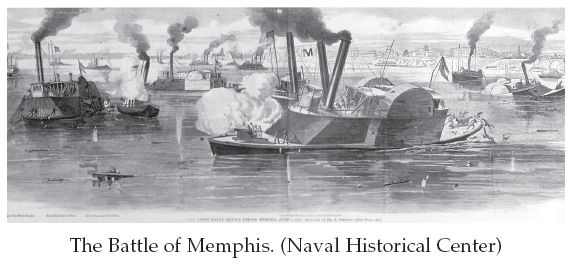

Union forces followed, and by early June Davis’s ironclads, Ellet’s rams, and army troop transports had reached Memphis and were facing the Confederate River Defense Fleet. At dawn on June 6, as crowds of Memphis citizens watched from the riverbanks, Davis’s ironclads Carondelet, Louisville, Cairo, St. Louis, and Benton lined up facing the Confederate rams. Suddenly, Ellet steamed his flagship, Queen of the West, through the ironclad fleet, to the cheers of their crews, and charged the rebels. Captain Henry Walke of Carondelet watched as “the rams rushed upon each other like wild beasts in deadly combat.” In the chaos and smoke of exploding and sinking Southern rams, the Union ironclads joined the fight, and the Confederate fleet was overwhelmed. Only one ram managed to escape to join the Southern defenders at Vicksburg. General Jeff Thompson watched the destruction of his frail cottonclads from the shore, and according to Captain Walke, commented “they are gone and I am going” as he mounted his horse and left the citizens of Memphis to the Union army.

The Union now held Memphis, the fifth-largest Confederate city with its huge store of cotton, its four railroad lines, and its Confederate navy shipyard, which Davis took over to repair and resupply the fleet. While in Memphis, Davis ordered St. Louis and Mound City, along with the Forty-sixth Indiana Infantry Regiment, up the Arkansas and White Rivers into the state of Arkansas to search for Southern gunboats. On June 17 the gunboats and infantry attacked Southern fortifications on the White at St. Charles. Sunken hulks in the rivers forced the two ironclads to advance single file. Mound City, in the lead, was hit in the main steam drum, and scalding steam filled the boat. As the surviving crew jumped into the river to escape, Southern sharpshooters “commenced murdering those who were struggling in the water, and also firing upon those in our boats sent to pick them up.” The outraged Forty-sixth Indiana silenced the snipers and seized the fort, but Mound City’s agony was not yet over.

When John Duble from Conestoga went aboard Mound City to relieve her wounded captain:

I beheld with extreme disgust a portion of the few men who were unwounded, drunk. A portion of the crew of St. Louis [and other sailors and soldiers] were in the same beastly condition. . . . Men while lying in the agonies of death were robbed. . . . Rooms were broken into, trunks pillaged . . . and destroyed. Watches of the officers were stolen, and quarreling, cursing, and rioting, as well as robbing, seemed to rule. . . . Not the first particle of order was observed. . . . While our doctor and nurses were rendering all relief in their power to the suffering, a portion of the crews seemed bent on destruction and theft. I hope never again . . . to see so much misery, such depravity, and so much disorder.

Duble recovered and buried fifty-nine of Mound City’s dead, but out of a crew of 175, some 82 had been killed in the steam explosion, 43 shot in the water, and another 24 scalded or otherwise wounded.

As the river level dropped and the gunboats repeatedly ran aground, St. Louis escorted her crippled sister Mound City to Memphis for repairs. Growing numbers of rebel snipers and guerrilla bands harassed the Forty-sixth Indiana, and the problem of guerrilla sharpshooters became so severe that on October 18, 1862, Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter issued a general order to the whole flotilla.

When any of our vessels are fired on, it will be the duty of the commander to fire back with spirit and to destroy everything in that neighborhood within reach of his guns. There is no impropriety in destroying houses [suspected of] affording shelter to rebels and it is the only way to stop guerrilla warfare. Should innocent persons suffer, it will be their own fault, and teach others that it will be to their advantage to inform the Government authorities when guerrillas are about.

At the end of June, Flag Officer Farragut invited Captain Davis to help attack Vicksburg, the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi. Davis told Secretary of the Navy Welles, “I leave at the earliest possible moment.” A month before Farragut had arrived from New Orleans with his warships and demanded that the city’s defenders surrender. The Confederates refused, and Union forces spent the next thirteen months trying to crack this last great rebel Mississippi River fortress. Davis’s flotilla arrived from Memphis on the first of July, but since most army troops had been ordered to Tennessee and Kentucky, the ironclads were stalled at anchor north of the town and its strong fortifications. As the hot, miserable southern summer dragged on, the Union sailors dropped from malaria and dysentery. According to Carondelet’s captain, his crew of “Northmen, considered the hardiest race in the world, melted away in the Southern sun with surprising rapidity.” Fortunately, the Union found a ready source of replacements. As the navy’s General Orders directed: “Owing to the increasing sickness in the Squadron, and the scarcity of men, it becomes necessary . . . to use . . . . contrabands. . . . [B]lacks will make efficient men. . . . The policy of the Government is to use the blacks, and every officer should do his utmost to carry this policy out.”

The decreasing number of healthy skilled sailors was not Farragut’s only worry. The water level of the Mississippi River was dropping so fast that his big seagoing ships could be stranded.

Vicksburg was protected by high bluffs and a maze of swamps, bayous, and rivers such as the Yazoo to the north and Big Black to the south. The Union navy’s great advantage was that gunboats, troops, and supplies could move with relative ease and speed by water while soldiers struggled with muddy roads or trails, thick swamps, and heavy forests. But the rivers also harbored Southern threats such as powerful ironclad rams. The South could not hope to match the size of the North’s fleets, but when Farragut stormed New Orleans in April he had faced the guns of the Confederate Manassas and the unfinished Louisiana and Mississippi. The Union fleet captured or destroyed all three. When Davis’s gunboats beat Montgomery’s rams at Memphis in June, the Confederate ram Tennessee was burned. Another unfinished ironclad ram, Arkansas, escaped from Memphis, and was dragged one hundred miles up the Yazoo River to Greenwood, Mississippi, to safety. Confederate navy Commander Isaac Newton Brown scraped together ten guns, found some iron to protect the front of the boat, and recruited a crew from the survivors of General Jeff Thompson’s Missouri guerrillas. While he struggled to complete Arkansas, Vicksburg commander General Earl Van Dorn urged him to attack the Union fleet. “It is better to die game . . . than to lie by and be burned up in the Yazoo.”

On July 15, 1862, Farragut ordered Davis to scout the Yazoo, and the ironclad Carondelet, wooden steamer Tyler, and ram Queen of the West started up the river. Without warning, they ran into Arkansas coming down. Carondelet was badly shot up and run aground. Arkansas chased the two light Union boats toward the Mississippi, but the fleeing Tyler managed to damage Arkansas so badly that when she finally reached the Mississippi, her engines could barely move her. Although they should have been warned by noise of the running battle, Farragut’s crews were caught unprepared; the ships had cold boilers and no steam to power their engines. The crippled Arkansas drifted downstream through the anchored Union fleet. Union cannons blazed away, but Arkansas survived and finally ran aground at Vicksburg. The furious and embarrassed Farragut sent his rams to try to destroy Arkansas, but she remained a dangerous threat.

As the river level dropped sixteen feet, Farragut gave up and moved his big ships back downriver in late July while Davis moved his ironclads upriver to Memphis. Vickburg remained in Southern hands. Indeed, the Confederates were so confident that in early August Arkansas and Major General John Breckinridge’s troops moved down to attack weak Union forces at Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Arkansas’s engines repeatedly failed, and she was destroyed by Union gunboats. Still, the Union forces withdrew from Baton Rouge. The Confederates again held the river from Vicksburg south. To block any new Union naval attack, they sent sixteen thousand troops to fortify the bluffs at Port Hudson, Louisiana.

After a successful spring in which the Union gunboats had moved south past Memphis and the Union fleet had advanced north past New Orleans, the summer of 1862 ended with the Confederates still holding the key to the Mississippi River valley. Congress created the new rank of rear admiral and promoted both Farragut and Foote. Davis became commodore of the U.S. Navy Mississippi River Squadron and was replaced in September by Acting Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter, Farragut’s foster brother.

Also in September 1862, since the U.S. Navy already had one St. Louis on patrol in the Atlantic off Europe, Eads’s City ironclad St. Louis was renamed Baron de Kalb. John, Baron de Kalb, a Bavarian soldier, had come to America with Lafayette during the Revolution to help fight the British. Appointed a major general in the Continental Army, he had been fatally wounded in the Battle of Camden, New Jersey, in August 1780.

The newly named Baron de Kalb stayed with her ironclad sisters and continued to play an important role in the battle for Vicksburg. In October, Ulysses S. Grant was made commander of the U.S. Army’s Department of the Tennessee, and in December, Porter’s ironclads escorted eighty-five transport boats carrying General William Tecumseh Sherman’s army back toward Vicksburg to renew the battle. Looking for a way around the heavily fortified town and bluffs, Porter sent Baron de Kalb, Cairo, and Pittsburg back up the Yazoo. The boats moved slowly, their crews clearing logjams and Confederate “torpedoes,” but on December 12, 1862, Cairo became the first ship in history to be destroyed by an electrical mine. Confederate sailors Zedekiah McDaniel and Francis Ewing were lying in ambush on the riverbank and set off two mines that sank Cairo in twelve minutes in thirty-six feet of water. (Cairo would lie on the bottom of the Yazoo for one hundred years. She was raised in the 1960s, and today this last surviving City gunboat is preserved at the Vicksburg National Military Park.)

Two weeks after the sinking of Cairo, Baron de Kalb again steamed up the Yazoo to destroy rebel shipping. After being blocked by winter weather and impassable swamps, the ironclads tried the Yazoo again in late February 1863. Baron de Kalb and Chillicothe led a group of transports with forty-five hundred soldiers up the Yazoo. Harassed by snipers, the sailors and troops slowly cleared logs and moved the fleet up to Greenwood, Mississippi, where on March 10, 1863, they were blocked by Fort Pemberton. Chillicothe was crippled by cannon fire, but Baron de Kalb returned fire and heavily damaged the fort; however, swamps prevented the Union troops from capturing the fort, and the expedition retreated in “miserable failure.”

The very next day Admiral Farragut brought his warships back up the Mississippi to Baton Rouge. To get to Vicksburg to join Grant and Porter, Farragut now had to brave the twisting river and powerful batteries at Port Hudson. On the evening of March 14, he led his fleet up to Port Hudson and disaster. Of Farragut’s big ships, only the flagship, Hartford, made it safely to Vicksburg. The old paddle wheeler Mississippi, sister to the first Missouri, ran hard aground under the merciless Confederate fire. Lieutenant George Dewey, who was to destroy the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay in 1898 to help win the Philippines for America, was second in command. Although he tried, he could not free the ship from the sandbar. The Mississippi’s crew set her afire so the Confederates could not capture her, and as she slid off the sandbar and sank, the heat of the flames caused her guns to fire. Dewey described her as “a dying ship manned by dead men, firing on the enemy.”

Even without Farragut’s big ships, the navy continued to support Grant’s advance on Vicksburg. As Grant moved his army south through Louisiana past Vicksburg looking for a place to cross the Mississippi, Porter moved Carondelet, Pittsburg, Mound City, and Louisville south to bombard Grand Gulf and cover the troops’ crossing. After suffering many hits from the powerful Grand Gulf batteries, the ironclads had to withdraw. Baron de Kalb had remained north of Vicksburg and escorted General William T. Sherman’s troops back up the Yazoo to distract the Confederates while Grant crossed the Mississippi and marched on the state capital at Jackson.

By mid-May, Jackson had fallen to Grant. On May 18, Baron de Kalb shelled Haines Bluff on the Yazoo as the Rebels fell back to join General John Pemberton’s twenty thousand defenders in Vicksburg. While the army surrounded Vicksburg and Port Hudson, navy mortarboats shelled the defenders. A Southern soldier reported that inside the tightening Union ring, the troops ate “all the beef—all the mules—all the dogs—all the rats.”

On July 4, 1863, Vicksburg fell. Porter was made permanent rear admiral, and one thousand miles away in Pennsylvania, Robert E. Lee began his long retreat from Gettysburg. Port Hudson fell on July 9, and as President Lincoln said, “the father of waters again flowed unvexed to the sea.” General Sherman congratulated Porter: “the day of our nation’s birth is consecrated and baptized anew in a victory won by the united navy and army.” On July 13, 1863, Secretary of the Navy Welles wrote: “To yourself, your officers, and brave and gallant sailors who have been so . . . persistent and enduring through many months of trial and hardship, and so daring . . . I tender, in the name of the President, the thanks and congratulations of the whole country.”

On the very day that Welles wrote with his congratulations, Baron de Kalb steamed up to the burning rebel shipyard at Yazoo City and hit two mines placed by Confederates in the Yazoo River. Although the crew suffered no casualties and were able to salvage the guns, the bow and stern were shattered; the Baron de Kalb could not be recovered. As late as 1930, her wreckage could be seen in the river at low water.

From the beginning of the war it had been clear that the Confederacy could not hope to match the Union in population, wealth, or industry, nor could the Confederate navy compete with the Union navy. Still, both the Union and the Confederacy showed that ironclad gunboats could be effective warships in inland rivers and protected harbors. Eads’s City gunboats helped the Union army reclaim the Mississippi Valley, and Virginia had almost broken the Union blockade of Norfolk. Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory concentrated his limited resources on these small and fairly simple river and harbor ironclads and, to protect his shipbuilding efforts from Northern attack, established primitive inland shipyards in such river towns as Richmond; Columbus, Georgia; Selma and Montgomery, Alabama; Yazoo City, Mississippi; and Shreveport, Louisiana, up small rivers far from Union forces.

By October 1862, with the Union blockade in place and Grant, Sherman, Porter, and Farragut preparing to again attack Vicksburg, Mallory had eighteen ironclads under construction. Although James Eads had faced great difficulties in building and arming his City gunboats a year earlier, his problems were simple compared to the challenges facing Mallory and his officers. In Shreveport, Louisiana, up the shallow and twisting Red River, Lieutenant Jonathan H. Carter signed a contract on November 1, 1862, for an ironclad to be completed in six months at a cost of 336,000 Confederate dollars (over three times the dollar cost of Eads’s City ironclads.)

Carter raced to finish his gunboat while Vicksburg still held out against the Union army and navy, and Secretary Mallory encouraged his officers to show energy and initiative: “You are a long ways from [the Confederate capital of] Richmond and must not hesitate to take responsibility. . . . Your . . . labors will be onerous.”

He did not exaggerate. Confederate navy officers were forced to compete with one another and with the Confederate army for supplies and men. They begged local army commanders for skilled carpenters, and Carter even “kidnapped” soldiers home on leave from the war. They built their boats of green unseasoned timber caulked with cotton and could scarcely find even such simple supplies as nails, pots and pans, and hammocks. Because Southern mills could not produce enough armor plating, Carter bought rails from railroads in the north Louisiana towns of Monroe, Alexandria, and Shreveport for his boat. By February 1863, as Union troops were throwing themselves against Vicksburg’s defenses, Carter’s boat was almost ready for its armor. He suggested naming the boat Caddo in honor of a local Indian tribe, but Mallory christened her Missouri. The Confederate Missouri was launched into the Red River on April 14, just a month after Admiral Farragut lost the Union Missouri’s sister Mississippi at Port Hudson.

Carter worried that the Red River was falling so low that his unfinished gunboat would be stranded. He considered moving downriver to Alexandria, although there his unarmored and unarmed gunboat would have been in danger of attack by Porter’s Union fleet. The battle of Vicksburg was growing more desperate, and General Pemberton had taken Missouri’s guns to strengthen his batteries at Grand Gulf. These guns helped beat off Porter’s gunboats, forcing Grant to move farther south to cross the Mississippi River to attack Jackson, Mississippi, and surround Vicksburg.

Missouri was now the only Confederate ironclad left in the Mississippi Valley, and Carter finally got two powerful naval guns from a captured Union gunboat. Missouri was officially turned over to the Confederate navy by her Shreveport builders in September, two months after the fall of Vicksburg, but her guns were not in place until December 1863. Looking very much like Eads’s City ironclads, Missouri was 183 feet long and 53 feet wide. Her armored casement to house her guns and protect her crew and machinery was built of timber two feet thick covered with about four and a half inches of railroad rails. She had two engines salvaged from river steamboats driving a 22-foot paddle wheel, but her top speed was only a disappointing six miles per hour. Badly armed, weakly armored, poorly built, underpowered, leaky, and slow, Missouri was also stranded far up a shallow and difficult river from the vastly more powerful enemy fleet. Her first captain, Lieutenant Commander Charles M. Fauntleroy, was so horrified at his new boat that he ungratefully told the long-suffering and hardworking Lieutenant Carter that “he hoped the damned boat would sink . . . he never intended to serve in her if he could help it.”

Fauntleroy soon departed, leaving Carter in command of the Red River Squadron of Missouri and the fast wooden steam ram Webb. Like Union Mississippi Squadron commander Captain Andrew Foote two years earlier, Carter now faced the problem of finding a crew for his new ironclad. He had earlier begged the army for craftsmen and guns; now he begged for crewmen. The army was of course reluctant to give up able-bodied soldiers, and in January 1864, Carter warned General Kirby Smith “should the time come when Missouri’s services will be required and no men on board, the fault will not be mine.” The army finally sent some cannoneers, but these men objected to performing the other duties expected of sailors, complaining that they only had orders to work the guns. Many soon returned to their army units, leaving Missouri again short-handed.

Carter’s warning to General Smith had been prophetic, for indeed the Union was planning a major attack up the Red River. Kirby Smith also predicted a Union attack up the Red and Ouachita Rivers before the rivers dropped too low for Porter’s fleet, and he ordered Carter to move Missouri down to Alexandria to support him. Both Secretary Mallory and General Smith were expecting Missouri to challenge the massed strength of Porter’s fleet, fresh from the victory at Vicksburg and the conquest of the entire Mississippi River.

The Battle of Memphis was the Mississippi River Squadron’s most decisive victory, and the Battle of Vicksburg was a wonderful example of army-navy cooperation. The Red River campaign of 1864 was almost the navy’s worst disaster. Union politicians and ambitious army officers wanted to seize Louisiana and Texas, in large part because of their rich stores of cotton. Admiral Porter agreed to support the army with his Mississippi Squadron once the Red River rose high enough in the spring to float his vessels. Along with lightly armored “tinclads” and two advanced Eads turret monitors, his fleet included City ironclads Mound City, Carondelet, Pittsburg, and Louisville. Easily reaching the prosperous central Louisiana town of Alexandria, Porter confidently wrote:

The efforts of these people [the Confederates] to keep up this war remind me very much of the antics of Chinamen, who build canvas forts, paint hideous dragons on their shields, turn somersets and yell in the faces of their enemies to frighten them, and then run away at the first sign of an engagement. . . . It is not the intention of these rebels to fight.

His sailors put their time in Alexandria to good use. Under regulations then in effect the army had to take possession of “enemy” cotton on behalf of the U.S. treasury. The navy, on the other hand, could seize it as a “prize of war,” with 50 percent of the profit going to the naval personnel involved, and 5 percent to Porter himself. To the outrage of the army, sailors even made up fake “Confederate States of America” stencils, painted the label on cotton bales, added “U.S. Navy” underneath, and loaded the “captured” bales on their ships. Admiral Porter was amused when an army colonel told him that “C.S.A./U.S.N.” stood for “cotton-stealing association of the U.S. Navy.” His gunboat crews received a quarter million dollars in prize money, and Porter personally got over twelve thousand dollars.

General Grant urged the army and navy to advance toward Shreveport and the waiting Missouri, but for the first time in a decade, the Red was failing to rise quickly enough for most of Porter’s fleet to clear the rapids above Alexandria. In early April, Porter dragged his flagship, Eastport, and eleven other gunboats, including his four “Cities” over the falls and moved upriver escorting thirty transports. As the boats passed piles of burning cotton, they were greeted by slaves from riverbank plantations. A soldier noted in his diary: “One group of color’d girls welcomed us with waving of handkerchiefs, bonnets and aprons and a song and a hurra for Lincoln too. . . . . ‘[It was a great day] when de Linkum gunboats come.’”

Despite low water and occasional groundings, the fleet quickly reached Springfield Landing some thirty miles south of Shreveport and Carter’s Missouri. At that point, Porter

found a sight that made me laugh. It was the smartest thing I ever knew the rebels to do. They had gotten that huge steamer New Falls River across Red River. . . 15 feet of her on shore on each side, the boat broken in the middle and a sandbar [forming under her]. An invitation in large letters to attend a ball in Shreveport was kindly stuck up by the rebels, [but] we were never able to accept.

Porter then learned that the Union army had been defeated and was retreating toward Alexandria, leaving him and his fleet stuck in the narrow, shallow river surrounded by Rebel troops. The retreat was a nightmare as boats ran aground, hit sunken logs and stumps, and broke rudders or paddle wheels. Porter was forced to blow up his flagship to keep it out of Rebel hands, and shortly thereafter two transports were ambushed. One was carrying 175 “contraband” former slaves from upriver plantations, and almost all were scalded to death by escaping steam when her boiler was hit.

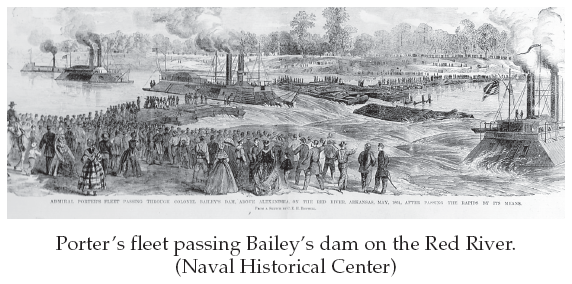

Porter’s battered fleet and exhausted crews reached Alexandria again at the end of April, where they discovered that the water over the falls was only three feet deep—less than half the seven feet of water needed to get his gunboats to safety. The navy feared that the army might abandon them and force Porter to destroy his Mississippi River Squadron to prevent its capture. Fortunately, among the soldiers was a Wisconsin engineer, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Bailey, who had served at Vicksburg and Port Hudson and had years of experience with shallow rivers. He proposed to build a dam to raise the water level enough for the fleet to clear the falls. Porter was skeptical, and punned “if you can dam better than I can you must be a good hand at it, for I have been ‘damning’ all night.” Still, the prospect of losing his fleet and facing professional ruin humbled him, and he assured the army “if he . . . can get me out of this scrape, I’ll be eternally grateful.” The Union general responded that “Colonel Bailey has been ordered to build the dam with all energy and vigor in his power.”

The challenge before Bailey seemed impossible. Porter’s gunboats faced two sets of falls with a total drop of 13 feet in a river 760 feet wide with a nine-mile-an-hour current. Despite widespread pessimism and gloom, Bailey organized 3,000 troops, 200 wagons, and 1,000 horses, mules, and oxen for the project. Troops cut down an entire forest on the northern, or Pineville, bank, and gathered lumber and rubble from Alexandria for materials to build the dam. The troops worked through the nights by the light of bonfires, and suffered through hot Louisiana days with little clean drinking water, as the Red was polluted with human and animal bodies. Soldiers and sailors risked drowning in the rushing river. Meanwhile, with some 6,000 men, the Confederates surrounded and trapped 31,000 U.S. troops. The Confederates also ambushed gunboats and troop transports between Alexandria and the safety of the Mississippi River. In the ten days needed to build Bailey’s dam and free the fleet, the Union lost 2 gunboats, 3 transports, and 600 men.

By May 8, the lighter monitors and gunboats had cleared the upper falls, but the army complained that the navy would not do enough to lighten the gunboats, such as abandon their heavy loads of captured cotton. On May 9 the rising river burst Bailey’s dam, and the unprepared navy was only able to get four gunboats through the rushing flood. All four “Cities” were left stranded above the falls. Finally, Porter’s sailors began working seriously. As the army built new dams, the gunboat crews unloaded guns and heavy supplies and even threw their iron armor into the river, painting the bare wooden sides of the boats black to fool the Confederates.

In their next try, Carondelet and Mound City stuck fast in the upper falls, but 3,000 troops dragged them clear. They then faced the rushing torrent of the lower falls, a “wild looking place to run a large gunboat into.” Mound City was the first City to brave the falls. Her crew sealed her gunports and ran the flood while thousands watched and army bands on shore played “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “The Battle Cry of Freedom.” The gunboat hit bottom and dragged and twisted through the rushing “niagara.” As the whole boat groaned and twisted, her crew was terrified that her steam joints might break and fill the sealed boat with deadly steam; they remembered that over a hundred of their crewmates had been killed on June 17, 1862, when her boiler was hit during the battle with the Confederate fort at St. Charles, Arkansas, on the White River. To the cheers of the watching crowd, Mound City survived the wild ride, and by May 13 Carondelet, Pittsburg, and Louisville were also clear.

As Union forces left Alexandria, arsonists set fires that swept the town, leaving the population homeless. The gunboats led the retreat south, shelling the treeline along the river to discourage Confederate attacks. By May 18, Porter wrote his mother, “I am clear of my troubles and my fleet is safe out in the broad Mississippi. I have had a hard and anxious time of it.”

Congress formally thanked Lieutenant Colonel Bailey and gave him a gold medal. Porter personally gave him a beautiful sword, and his naval officers gave him a silver punch bowl. He ended the war a brigadier general and then settled on a farm in Vernon County, Missouri. Elected sheriff, he was murdered on March 21, 1867, by two prisoners he was taking to jail.

The Red River campaign was a near disaster for Porter’s fleet. Between December 1864 and April 1865 Congress held hearings on the campaign, concluding that the “only results, in addition to the disasters that attended it, were of a commercial and political nature.” One ironclad captain called the navy’s experience “one of the most humiliating and disastrous that had to be recorded during the war.” Lieutenant Carter never got into the fight as Missouri remained stranded at Shreveport because of shallow water dowstream. Finally, in January 1865, Carter received army recruits to fill out his crew: “wild Texans and men who have never seen a gun or ship.” At the end of March, the Red rose enough for Missouri to move downstream. Carter wrote the Confederate general in command: “I will . . . be pleased to welcome you on the deck of the Missouri. . . . I hope to be a valuable [addition] . . . to your forces defending the [Red River] valley.”

On April 8, Missouri reached Confederate forts at the rapids above Alexandria. The next day, Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox in Virginia. On May 2, Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory resigned as President Jefferson Davis fled from Richmond. At the end of May, Union Lieutenant Commander W. E. Fitzhugh brought a small Union flotilla upriver to take possession of Confederate navy personnel and property on the Red. He

met no resistance whatever . . . and [on June 3, 1865] met Lieutenant-Commanding J. H. Carter, commanding Naval Forces, Trans-Mississippi Department, and received from him the ironclad Missouri [and the surrender of his] officers and men . . . . Missouri . . . is a very formidable vessel, plated with railroad iron. She . . . leaks badly, and . . . is very slow.

Missouri was brought to Mound City, Illinois, to join the ironclads of the Union Mississippi River Squadron being dismantled. Along with the surviving City ironclads Carondelet, Louisville, Mound City, and Pittsburg, she was disarmed and decommissioned. At the end of November, Missouri was sold for scrap for $2,100. Although never firing a shot in anger, Missouri had the distinction of being the last Confederate ship to surrender on American territory.

The Union Mississippi Squadron, once one hundred ships strong, was dissolved on August 14, 1865, and only Cairo remains of Eads’s seven City ironclads. From their very first action against Forts Henry and Donelson it was clear that St. Louis and her sisters were quite vulnerable. Heavy cannonballs sent wooden splinters flying around the gundeck or entered gunports to knock over guns, kill crewmen, or burst machinery and release scalding steam. The armored pilothouses were often hit, killing or injuring skilled river pilots or commanding officers. The slow and clumsy boats could be rammed by faster Confederate cottonclad river rams or overwhelmed by more powerful Confederate ironclads like Arkansas. Finally, they could be sunk by mines in the narrow western rivers. Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter, who commanded them at Vicksburg and almost lost them at Alexandria, recognized that they were “temporary expedients” that “suffered a great deal.” Still, they proved sturdy and dependable. As Porter said: “No vessels have done harder fighting anywhere. . . . Some of them have been sunk and others badly cut up, but they have seldom failed to achieve their objectives, and have opened or have helped to open, over 3500 miles of river once in the hands of the enemy.”