CHAPTER THREE

The Great Naval Arms Race and the First World War

Decline and Rebirth—A New Missouri and Two Named St. Louis

At the end of the Civil War the United States had the most experienced, most powerful army and navy in the world, but within two years hundreds of ships had been cut from the huge 671 ship wartime fleet. In 1865 the navy had 7,000 officers and 51,500 men, but by December 1867 only 2,000 officers, 12,000 men, and 103 ships remained. When David Farragut died in 1870, David Dixon Porter became senior admiral of the navy until his own death in 1890, and the U.S. Navy returned to the comfortable prewar practice of using tiny American squadrons to protect American commercial interests around the world.

The American navy had experimented with many technological advances, and steam power, armor, gun turrets, naval guns, and ammunition had quickly improved in the laboratory of a four-year war. European naval experts had watched the American experience with intense interest, and the great European powers quickly exploited rapid technological developments in ship design, steam power, steel-making, and weaponry to build ever-more-advanced warships. At a time when Admiral Porter was ordering American ships to use only sail and threatening to charge captains personally for the coal if they ran their engines, the British were abandoning sail for coal and building steam-driven armored ships, like Dreadnought in 1875, that were clearly the direct grandparents of the great battleships of the twentieth century, including the last Missouri. These new British battleships carried their big guns in turrets in front of and behind their bridges and smokestacks and were designed to destroy other battleships in the open seas anywhere in the world.

Over the next decades European nations spent hundreds of millions of dollars building even more powerful battleships and increasing their war fleets. Europe competed not only for the strongest fleets, but for the most foreign colonies and naval bases in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific Ocean. Few Americans were willing to pay to join the race for more modern warships and bigger fleets. Indeed, when Americans thought there might be war with Spain in 1873 over brutal Spanish treatment of their Cuban colony, Admiral Porter said “it would be much better to have no navy at all than one like the present,” which was much weaker than the Spanish fleet. As late as 1889 the U.S. Navy ranked twelfth in the world in size, weaker than the navies of such countries as Turkey, China, and Austria-Hungary.

Still Americans were concerned about European naval advances and imperial competition for colonies. Since the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, America had warned European states to leave Central and South America alone to develop free democracies. Americans were especially angered by Spain’s treatment of Cuba, and the ruthless suppression of rebels. At the same time, American sailors saw that modern coal-burning battle fleets required coaling stations and repair bases at strategic locations like Hawaii. Americans also saw that to defend the country’s Atlantic and Pacific coasts, a canal through Central America that would allow the fleet to move quickly to counter a Spanish, or later a Japanese, threat would be very desirable. Indeed, by the mid-1890s, Americans were growing increasingly worried about Japan. Many Americans feared waves of Japanese immigrants, and in 1897 American businessmen who had overthrown the Hawaiian royal family deported one thousand Japanese. In response to this insult, the Japanese sent a threatening cruiser to Hawaii. The new assistant secretary of the navy, Teddy Roosevelt, wanted to annex Hawaii to keep the islands from the Japanese and to serve as a base to protect Panama and the American West Coast.

The crisis came not from Japan, though, but from Spain. Both Cuban and Filipino guerrillas were battling Spanish colonial authorities, and in January 1898 the navy sent the small, new, but already obsolete 6,500-ton second-class battleship Maine to Havana harbor to discourage Spanish-led anti-American riots. On February, 15, 1898, a terrible explosion destroyed Maine and killed 260 of her crew. To this day, the exact cause of the explosion is unknown, but it appears likely that the ship was destroyed by an accidental fire in the coal supply that set off ammunition. American newspapers and many citizens blamed Spanish sabotage, and Congress immediately appropriated $50 million to expand the navy.

The United States government demanded Cuban independence, called for 125,000 volunteers, and declared a blockade of Cuba. To supplement the small American fleet, the navy took over private merchant ships, including a 15,000-ton Atlantic passenger liner called St. Louis. She had been built in Philadelphia in 1894, the same year that the original naval sloop St. Louis was lent to the Pennsylvania Naval Militia in Philadelphia as a training ship. St. Louis had been in transatlantic service for three years when the navy armed her with 12 guns and commissioned her a U.S. Navy auxiliary cruiser. With a speed of 23 miles per hour she was faster than the most modern battleships. On April 30, 1898, commanded by Captain Casper Goodrich and with a crew of 27 officers and 350 men, St Louis sailed from New York to join the American fleet in the Caribbean.

By the time St. Louis arrived off Spanish Puerto Rico in the second week of May, Captain George Dewey had already won a great naval victory on the other side of the world. Thirty years after serving aboard the old Mississippi at Port Hudson, Louisiana, he had supervised the sea trials of the navy’s newest and most powerful battleships. On May 1, 1898, in an astonishing victory, Dewey’s squadron of five cruisers destroyed the Spanish Asian fleet at Manila Bay. The forts and city of Manila surrendered to the navy, and the United States soon won the Philippine Islands as part of America’s new empire. Against the destruction of ten Spanish ships and the loss of almost four hundred killed or wounded, Dewey’s fleet did not lose a single man.

With Dewey’s great Pacific victory, the navy now prepared to meet another Spanish fleet steaming across the Atlantic toward Cuba and Puerto Rico. As the American fleet blockaded Cuba and waited for the Spaniards to appear, Captain Goodrich’s St. Louis played an important role in helping to isolate Spanish defenders on the Caribbean islands. Underwater telegraph cables had first been laid before the Civil War, and by the end of the nineteenth century many Caribbean islands were connected by such cables. St. Louis was fitted with heavy drag lines to snag and cut Spanish undersea cables, and on May 13, 1898, cut the telegraph line connecting San Juan, Puerto Rico with St. Thomas in the Danish Virgin Islands. A week later St. Louis exchanged fire with the forts guarding Santiago de Cuba, and cut the cable between this port and Jamaica. The next day the arriving Spanish fleet slipped unnoticed past the patrolling American fleet and reached the safety of the harbor of Santiago de Cuba. St. Louis next cut the Guantánamo Bay—Haiti and Cienfuegos cables to completely isolate Cuba. The Spanish fleet was safe from the blockading American battleships but cut off from Spain.

In June St. Louis helped bombard the fortifications at Guantánamo Bay, captured a Spanish merchant ship, and intercepted two British freighters sailing to Cuba. With his ships threatened by advancing American and Cuban troops, the Spanish admiral decided to try to break through the American blockading force on July 3, 1898. The American warships, whose engineers and coaling crews worked feverishly in terrible heat to feed their furnaces, quickly caught and overwhelmed the Spanish ships. Their admiral ran his flagship aground on the Cuban coast and swam ashore with most of his sailors. As at Manila Bay, the entire Spanish fleet and hundreds of Spanish sailors were lost. Only one American was killed. Thirty-five years after an earlier St. Louis and the other Eads City ironclads helped Grant and Sherman capture Vicksburg, Rear Admiral William Sampson telegraphed to Washington: “the fleet . . . offers the nation, as a Fourth of July present, the whole [Spanish] fleet.”

The new auxiliary cruiser St. Louis was one of several smaller navy ships in the blockading squadron watching as the powerful new American battlefleet destroyed the outmatched Spanish cruisers. As a former passenger liner, she transported hundreds of prisoners of war, including their admiral, to Plymouth, New Hampshire. The Battle of Santiago de Cuba effectively ended the Spanish-American War. In September, St. Louis was returned to her civilian owner and resumed passenger service between New York and Liverpool, England, until she was again required for navy service in World War I.

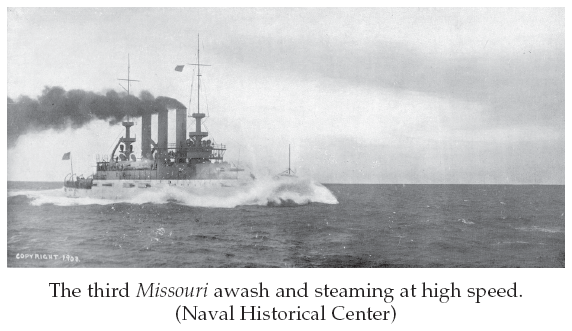

The United States was delighted at the great victories won by the American navy, and many felt that powerful armored battleships and cruisers armed with heavy long-range guns were the decisive modern weapons of ocean warfare. As part of the American war fever following the destruction of Maine in Havana harbor, Congress had approved the construction of three new 12,000-ton battleships to add to the ten already in the fleet or under construction. Three days after Dewey’s victory in Manila Bay, Congress gave final authorization for these three Maine class “sea-going coast-line” battleships—Maine, Missouri, and Ohio. Powered by 16,000 horsepower coal-fired reciprocating engines that gave them a top speed of 20 miles per hour and a range of 4,900 miles, they were the first American battleships protected by new high-strength 12-inch armor. Missouri and Ohio were also the first American battleships equipped with radios. In two electrically powered turrets they carried four 12-inch main guns built in the Washington Navy Yard gun factory. With very powerful new smokeless gunpowder designed to ease the gunsmoke that had almost caused American warships to ram each other during the confused battle of Santiago de Cuba, the main guns could fire 870-pound shells 15,000 yards, or almost 8 miles. They also carried sixteen 6-inch rapid fire guns for defense against fast torpedo boats and two torpedo tubes to attack enemy battleships. The ships were 393 feet long and 72 feet wide—twice the size of Eads’s Civil War gunboats but only a bit bigger than British warships like Dreadnought of a quarter-century earlier. Because Congress intended them for coastal defense rather than worldwide all-weather service, these early American battleships were as heavily armed and armored as their European counterparts, but they tended to be somewhat smaller and lower in the water, with less coal storage. This made them less suited to long cruises or rough seas and stormy weather. Like all early American battleships they suffered from poor ventilation, which made them almost unbearable in hot weather. They were also so wet in heavy seas that many of their smaller guns and their torpedos could not be used because of flooding.

The three sister ships were built in different private shipyards and cost about five million dollars each. Missouri was built by Newport News Shipbuilding in Virginia. Her keel was laid in February 1900, she was launched in December 1901, and commissioned two years later on December 1, 1903. She carried a crew of forty officers and over five hundred men, and one of her young midshipmen was William F. Halsey Jr., who would later gain fame as Admiral “Bull” Halsey in World War II. Members of the Missouri Daughters of the American Revolution knitted clothing for Missouri’s crew.

In February 1904 Missouri left Hampton Roads for Guantánamo to join the Atlantic Fleet. On April 13, while practicing with her main guns off Pensacola, Florida, Missouri suffered a terrible accident in her rear turret. Hot gases ignited 340 pounds of powder in the turret and 720 pounds in the shell-handling room below. While the powder did not explode, it burned and suffocated over thirty crewmen in the turret and handling room. The turret was quickly flooded to put out the fire before it reached the main magazine and destroyed the ship. As the deadly powder fumes cleared, a team of sailors went into the magazine to inspect the damage. Three of them discovered that the twelve-inch magazine, filled with one thousand pounds of powder, was still afire. Gunner’s mate Mons Monssen, a native of Norway, threw water on the fire with his hands. Gunner Charles S. Schepke stayed with Monssen while acting gunner Robert E. Cox fetched a hose with which they extinguished the fire and saved the ship. The three were awarded Medals of Honor for their heroism.

Missouri’s dead were given a huge military funeral, and the accident caused a long and bitter debate about whether U.S. Navy firing procedures, ammunition handling, and turret design were safer against accident or enemy shellfire than modern foreign battleships.

Following repairs, Missouri joined other Atlantic Fleet ships in a visit to the Mediterranean, home of one of the British Royal Navy’s strongest fleets. In October 1905 her squadron escorted a British squadron back to New York. During 1906 Missouri won marksmanship awards for her main twelve-inch guns, six-inch guns, and torpedoes. By August 1906, according to a navy newsletter, “Missouri has been making a record . . . this year . . . nothing short of distinguish[ed]. . . . First in target practice of the Atlantic Fleet, first in the football games, first in the rifle practice, first in the pulling races.”

In January 1907 Missouri landed sailors and marines in Kingston, Jamaica, to help the residents following an earthquake and fire. The local British governor was embarrassed by the absence of British ships and was offended that American ships began humanitarian action without first saluting the British flag. He resigned as governor after his demand that the U.S. Navy withdraw caused an international scandal, but his hurt feelings contributed to a cool reception for Missouri and the rest of the fleet when they next visited Jamaica on their around-the-world cruise at the end of the year.

Great Britain had been the greatest naval power in the world for over a hundred years, but at the beginning of the twentieth century she was challenged by a growing American navy and by new regional naval powers Germany and Japan. Britain viewed Germany as the more serious threat, but many Americans, especially those in the West, were prejudiced against Asians. Although Chinese laborers had helped build the transcontinental railroad forty years earlier, California had passed anti-Chinese laws. American businessmen in Hawaii had angered Japan in 1897 by expelling Japanese laborers, and in 1906 California’s anti-Asian policies again angered and insulted Japanese leaders.

In April 1906, San Francisco was struck by an earthquake and a fire that killed thousands and left over half of the city’s 400,000 residents homeless. Many of San Francisco’s 74 schools were also destroyed, and in October the San Francisco school board forbade Asian children to attend school with American children. There were also anti-Japanese attacks and riots and wild newspaper stories claiming that the Japanese navy would attack California without warning. Japan protested the treatment of its citizens, and a Japanese newspaper urged: “Stand up, Japanese nation! Our countrymen have been humiliated. . . . Our poor boys and girls have been expelled from the public schools by the rascals of the United States, cruel and merciless like devils. . . . Why do we not insist on sending ships?”

The Japanese reached a “gentlemen’s agreement” with President Teddy Roosevelt under which Japan agreed not to allow any further labor migration to America if the U.S. agreed not to formally exclude Japanese workers. This humiliating agreement was strained by further anti-Japanese riots in San Francisco, and war hysteria arose in popular newspapers in both countries. Roosevelt was denounced in the San Francisco Chronicle: “Our feeling is not against Japan, but against an unpatriotic president who unites with aliens to break down the civilization of his own countrymen.” The president expressed his anger at the “infernal fools in California” who “insult the Japanese recklessly” and the

worse than criminal stupidity of the San Francisco mob, the San Francisco press, and . . . the New York Herald. I do not believe we will have war, but it is no fault of the . . . [tabloid] press if we do not have it. The Japanese seem to have about the same proportion of prize . . . [super-nationalist] fools that we have.

The crisis eased, but heightened public attention to America’s vulnerable Pacific coast gave Roosevelt the opportunity to make a bold military and diplomatic gesture to underline United States world status and naval power. From its beginnings as a slender string of colonies hugging the Atlantic coast, America had focused its attention on the European powers. Even as the United States expanded to reach across the continent, its diplomatic and military efforts remained attuned to European rivals and threats; however, it could not ignore the possibility of attack from the west. In order to connect the two coasts of the country more quickly, and avoid the long, dangerous voyage around Cape Horn at the bottom of South America, a railroad was built through Panama in the 1850s to shorten the trip from Atlantic to Pacific. In the 1880s the French, after building the Suez Canal to connect the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean, tried unsuccessfully to cut a canal through Panama. Since 1903, when America had encouraged Panama to revolt and declare independence from Colombia, the United States had been spending hundreds of millions of dollars and using tens of thousands of workers to cut a new Panama canal for commercial and military purposes.

The Japanese war scare made many Americans think that the West Coast might need more protection against enemy attack and that the navy should make plans to move the new fleet into the Pacific if danger threatened. Roosevelt was unwilling to divide his battleships between Atlantic and Pacific bases, and with the Panama Canal unfinished, he decided to send the whole fleet on a “training” cruise to the Pacific. He wanted to show Japan that America could mass military strength in the Pacific if necessary, to encourage popular support and funding for the fleet, and to emphasize the need to complete the Panama Canal.

While Californians were delighted that the fleet would visit San Francisco, easterners expressed alarm at the cost of moving the whole fleet and fear that the Atlantic coast would be left defenseless. Wild and irrational rumors flew that the German Navy might suddenly attack America or that the Japanese might try to sabotage the fleet.

Roosevelt’s plan was incredibly ambitious. No navy had ever succeeded in such a complicated voyage. Would the engines and machinery hold up? Would the “coastal defense” battleships be able to withstand wild ocean storms? Would the navy be able to supply the 90 tons of coal that each battleship would consume every day—1,500 tons a day for the entire fleet? Would the officers and crews be up to the challenges of such a long journey? And would the trip leave ships and crews so worn out that they would take months to recover?

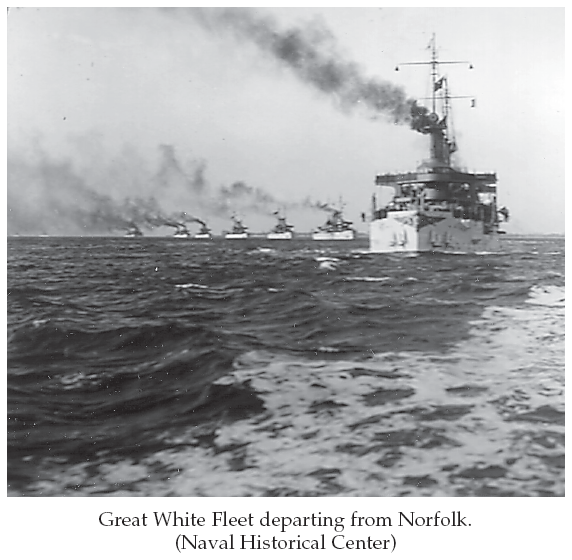

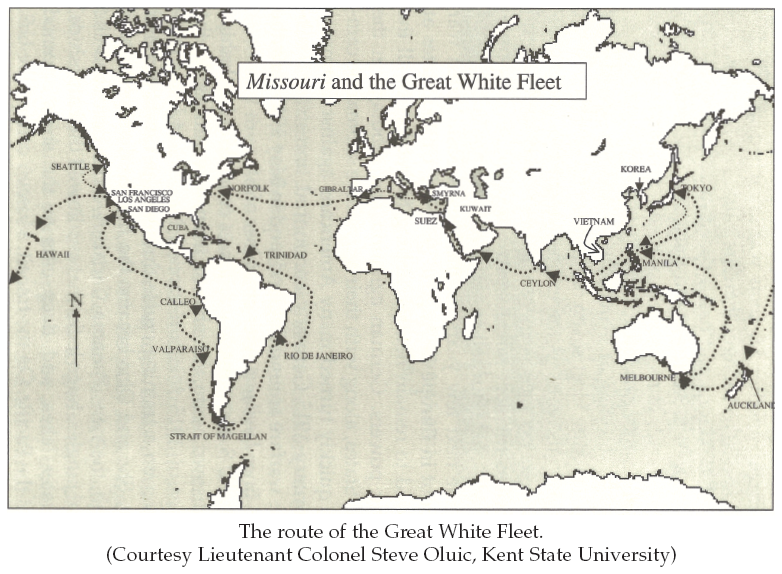

At first, Roosevelt hid the full extent of his plans, perhaps fearing that the fleet might not be able to face the challenge before them. Atlantic Fleet commander in chief, Rear Admiral Robley D. “Fighting Bob” Evans, ordered his sixteen battleships, from the seven-year-old 11,000 ton Kearsarge and Kentucky to the brand-new 16,000 ton Virginia, Connecticut, and Vermont class ships, to prepare for a long cruise and assemble in early December 1907 in Hampton Roads, Virginia. The navy planned five coaling stops all around South America, and chartered a fleet of foreign-owned coal ships to help supply the 125,000 tons of coal that the fleet was expected to burn during the voyage to California.

Thousands of Americans flocked to Norfolk and Hampton, Virginia, to see the fleet off. Not all of the 13,000 sailors in the fleet were able to celebrate the adventure, however. A number of Japanese had joined the navy as cooks and officers’ servants. Some naval officers feared that these crewmen might remain loyal to Japan and try to sabotage their ships if they ever faced the Japanese navy. Seventy-two Japanese were therefore removed from the ships just before departure. One was so upset at being suspected of disloyalty that he tried to drown himself.

After weeks of storm and blizzard, Monday, December 16, 1907, was a clear bright day. The sixteen battleships, painted gleaming white, their rigging covered with flags, were reviewed by President Roosevelt, who exclaimed “Did you ever see such a fleet! Isn’t it magnificent?” Admiral Evans had assured Americans “you will not be disappointed in the fleet, whether it proves a feast, a frolic, or a fight,” and Roosevelt clearly agreed. He summoned the admirals and captains for a last farewell and shook hands with them all, including Captain Greenlief Merriam of Missouri. The ships offered many twenty-one gun salutes; a band played “The Star-Spangled Banner” and other patriotic and popular tunes; finally, the presidential yacht led the fleet in a column almost four miles long out into the Atlantic Ocean. As the ships headed south, newspapers all over the world offered opinions on the cruise. The Berliner Tageblatt called it “the greatest naval experiment ever undertaken by any nation in time of peace,” and a Japanese newspaper predicted “should the American fleet visit . . . it will be given a . . . reception worthy of the special friendship between Japan and the United States.”

Admiral Evans immediately began the hard work of turning the sixteen ships’ raw crews of inexperienced recruits and new captains into a disciplined fleet. The battleships were formed into four divisions, with the newest ship, Minnesota, and the older sister ships Maine, Missouri, and Ohio in the third division under Rear Admiral Charles Thomas. The ships sailed in close formation, each one following at four hundred yards from the one in front, a feat demanding great skill and attention from officers, engineers, and crews to keep accurate speed and position as the fleet maneuvered. On the first night at sea, Admiral Evans tried to ease the curiosity of officers and men in a radio message to the fleet announcing that after their visit to San Francisco, they would return home by way of the Suez Canal—in other words, by steaming west across the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic Oceans and around the world. The radio message was intended only for the fleet but was heard ashore, and this sensational news was published in American newspapers. President Roosevelt immediately denied the newspaper reports, still not confident that the ships and men could succeed in such a long journey.

Indeed, as the fleet sailed down the East Coast, some ships suffered mechanical breakdowns, and “children’s diseases” like mumps, scarlet fever, chicken pox, as well as more serious illnesses, began to strike the crews of the crowded ships. Missouri reported a case of typhoid fever and stopped in Puerto Rico to drop off the sailor before he infected the whole crew. Alabama lost a man to spinal meningitis, and the fleet paused while he was buried at sea.

Two days before Christmas, after steaming 1,800 miles, the fleet reached Port of Spain, Trinidad, for its first coaling stop. Admiral Evans, who had been crippled during the Civil War, had to be supported by two junior officers as he and his admirals went ashore to a polite but cool British reception. Perhaps they were still unhappy about the incident involving Missouri in January or embarrassed at the arrival of the Great White Fleet of 16 gleaming American battleships when the proud royal navy did not have a single warship in port. The British governor discouraged local businessmen from holding a ball in honor of the visitors, and when the British military invited 250 American officers to a reception, only a handful of senior officers showed up. Still, many sailors went ashore to play baseball, shop, and mail thousands of postcards home, and they behaved so well that in the end the British governor congratulated Admiral Evans on their conduct and discipline.

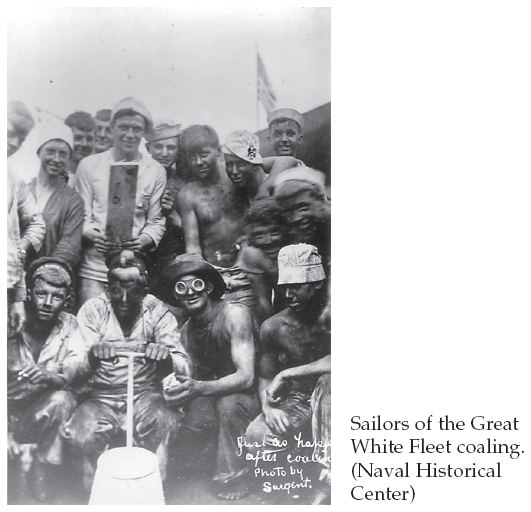

The main purpose of the visit, of course, was to refuel the ships for the long voyage to South America. Loading the ships with coal was the dirtiest, most unpleasant duty in the early steam navy, and all officers and men wore their oldest clothes for this job. The ships’ bands played ragtime music to encourage the men, and they worked during the entire visit except on Christmas day. Finally the sailors scrubbed off all the black coal dust that covered the ships and themselves. This dirty, backbreaking job would be repeated at every port during the next fifteen months as they sailed around the world.

The White Fleet left port on December 29, minus 60 sailors who had deserted rather than continue the journey. According to records, Missouri was a relatively unhappy ship, losing 94 men in 1907. Only three battleships lost more. In 1908 only two ships lost more, with Missouri suffering 108 desertions. The ships celebrated New Year 1908 at sea with homemade costumes and music, but the biggest celebration was several days later when the fleet crossed the equator and entered the southern hemisphere. For 12,000 of the 14,000 members of the fleet this was their first crossing, and King Neptune and his court visited every ship to initiate his new subjects by shaving their heads, painting their faces with flour and molasses, and dunking them in water tanks.

Such celebrations kept up the sailors’ morale and pride, but Evans and his officers soon received an unpleasant surprise. They had underestimated the distance between Trinidad and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil—some 3,400 miles—by at least 400 miles. The admirals feared that some of the older or less efficient ships might run out of coal, and Admiral Thomas wrote “it would be awful if we were compelled to tow these ships into port.” Evans ordered strict economy, including slower speed, less attention to tight formation, and even restrictions on electric lighting and freshwater bathing. The fleet was further slowed by a mistaken report from Missouri that a sailor had fallen overboard.

Fortunately, Missouri had not lost a crewman, and the coal held out. The fleet reached Rio on January 12, 1908, to an enthusiastic welcome by South America’s biggest and most powerful country. The senior officers immediately began a heavy schedule of official diplomatic ceremonies, although Admiral William Emory complained of having to wear his heavy wool formal uniform in the tropical summer: “the good Lord never afflicted such misery on a human being as He did upon me.” Rio welcomed the American sailors, and despite a few brawls and stabbings, a Brazilian newspaper praised the “youthful and orderly” sailors. The sailors were of course less happy to again have to coal the ships for the 2,000-mile run down to the Strait of Magellan at the tip of South America.

The fleet and their Brazilian hosts had received warnings from around the world that the Japanese or Germans, or even European anarchists, might attack the ships with mines or try to sabotage the coal supplies. Although the stories proved groundless, the Japanese navy took the remarkable step of giving the American embassy in Tokyo daily reports of the location of Japanese warships. While the Brazilians expressed great friendship for America, the Americans did not forget that they had just ordered three powerful new British “dreadnought” battleships—stronger, faster, and more deadly than any of the American White Fleet. The fleet intelligence officers thus made careful note of Brazilian defenses, although one junior officer warned his mother: “please don’t tell anyone that officers . . . do such things because some people might think it wasn’t . . . courteous.” The fleet left Rio on January 22, and Admiral Evans established a competition among the ships with prizes and rewards for the ship that could save the most coal and steam most economically.

The officers and men responded so enthusiastically to this challenge that the fleet managed to cut its coal consumption by 20 percent during the rest of the cruise. During the passage down the Atlantic coast of South America, the crews practiced with advanced new technology. First, they finished installing telephone fire-control systems so the officers could more accurately direct the aim of the ships’ big guns. Although the American navy had won great victories at Manila Bay and Santiago de Cuba, gunnery officers discovered that only one or two shells of every hundred fired hit the enemy ships. Modern navies, including the American fleet, invested much effort and thought in new scientific technology to improve the power and accuracy of weapons. The White Fleet was also equipped with radios so the admirals could direct all their ships, no matter the weather or distance between them. During the 2,300-mile journey to the Atlantic end of the Strait of Magellan, the admirals and captains practiced controlling and maneuvering their battleships using this new “wireless” communication tool.

The navy’s torpedo squadron escorted the battleships as they navigated the dangerous final 140 miles to the Pacific Ocean. The strait was made dangerous by its many small islands and frequent fog, but the torpedo boats were there to guard against such imagined enemies as German or Japanese mines or submarines that fearful Americans—encouraged by hysterical newspaper editorials—thought might be lurking in ambush.

The fleet reached the Pacific safely, and on Valentine’s Day 1908 it made a brief but spectacular visit to Valparaiso harbor where the ships put on “the most magnificent marine pageant ever seen in the Pacific Ocean, and probably in the whole world.” Seventeen years earlier Captain Robley Evans in command of Yorktown had threatened to shell Valparaiso during confrontation between the Chilean and American navies, but this time the fleet made a great loop through the harbor, flying Chilean flags and firing twenty-one-gun salutes to Chilean president Pedro Montt. Admiral Thomas proudly called the performance the most “perfect exhibition of Marine Efficiency, power, and drill . . . in the World’s history.”

Four days later the fleet arrived in Callao, Peru, and in honor of the visit President Jose Pardo declared George Washington’s birthday a national holiday. The Peruvians staged a grand bullfight to entertain three thousand American sailors, but many were so appalled by the cruelty of the sport that they cheered for the bulls and left the stadium early.

As the fleet reached Mexico, Rear Admiral Evans radioed the Navy Department to announce the arrival of the fleet, and the whole country celebrated the navy’s remarkable success in moving the fleet from the Atlantic to the Pacific coasts. Admiral Thomas boasted that the fleet had arrived in better condition than when it had left Norfolk four months earlier. The crews were well trained and strong, the officers were skilled, and the engineers had learned to maintain and repair the ships’ engines and machinery themselves without having to depend on shipyard repair shops. President Roosevelt was so delighted at the condition of the fleet that he allowed the navy to officially announce that it would return home across the Pacific and through the Suez Canal—something he had denied when the fleet left Norfolk.

When the Great White Fleet finally reached the coast of California on April 14, 1908, the progress of the ships from San Diego to San Francisco turned into one huge celebration. San Diego set bonfires on the beaches, and young women bore bouquets of flowers out to sea to spread around the battleships. As the ships steamed toward Los Angeles, huge crowds came to the shore to watch them pass, and tens of thousands camped overnight on beaches in San Pedro, Long Beach, and Santa Monica to await their arrival. To allow more people to see the ships, the divisions anchored at different ports. Missouri and her Third Division sisters Minnesota, Ohio, and Maine went to Santa Monica. The Los Angeles visit was not altogether happy. Because Easter Sunday fell during the visit, local churches tried to get the city to close the saloons during the entire time the ships were in port. One local leader wrote commander Admiral Thomas, “It will certainly be a proud day when [we can say of the navy] not a man of them is known to drink, on duty or off.”

Even worse happened in Santa Barbara. A number of wives had traveled across the country for brief visits with their sailor husbands. Santa Barbara restaurants and hotels raised their prices so high and treated the sailors so badly that hundreds of them rioted, breaking windows and forcing the owners to flee.

As might be expected, the welcome in San Francisco was much warmer, since that city’s anti-Japanese school policies had inspired the cruise in the first place. Local citizens raised thousands of dollars to entertain the fleet, with the Japanese community giving one of the largest contributions. More than a half million people filled San Francisco, Oakland, and the hills of Marin County to await the fleet.

On May 6, to the cheers of the vast crowd, Admiral Evans led the combined fleet through the Golden Gate and paraded his forty-six warships down San Francisco Bay and back up to the city. One spectator wrote “our hearts beat high with pride in our own country, and in the sure protection of its invincible strength.”

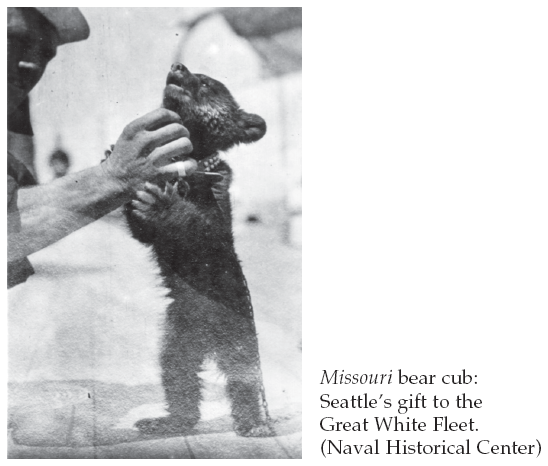

As a highlight of the visit 7,500 sailors and marines marched through the city in the largest military parade ever held on the West Coast. Admiral Evans was given a jeweled sword by the people of San Francisco, and the sailors and officers were entertained with parties and tours. After the fleet left San Francisco it made a brief visit to Washington, where 400,000 people flocked to the small city of Seattle in Puget Sound to see it and watch yet another “monster parade.” The people of Seattle gave each battleship a bear cub as a mascot to add to the zoo that each ship already carried. The sailors loved pet animals, and pigs, goats, monkeys, cats, dogs, and parrots filled the ships. The fleet had even carried a full-grown tiger until he jumped overboard into the Strait of Magellan and was lost.

Freshly painted, refueled, and repaired, the Great White Fleet returned to San Francisco in early July to head west toward Asia. Captain Merriam was replaced as Missouri’s captain by Commander Robert Doyle, who would bring her back home. Many Californians wanted the Atlantic Fleet to remain permanently, and the city of San Diego appealed to President Roosevelt to leave the fleet to defend the Pacific coast. Roosevelt, however, sent the fleet a message of praise and farewell: “Heartiest good wishes . . . the American people can trust the skilled efficiency and devotion to duty of the Fleet. . . . You have . . . the honor of the United States in your keeping and no . . . men in the world enjoy . . . a greater privilege or carry a heavier responsibility.”

The new American colony of Hawaii declared the arrival of the fleet a holiday, and thousands of people waited on Diamond Head to see the ships appear. The admiral detoured past the island of Molokai so the inhabitants of the leper colony there could see the parade of ships and then arrived in Honolulu to the welcome of a fleet of decorated passenger steamers. Although the United States had annexed the remote and exotic Hawaiian Islands fifteen years earlier, in part as a naval base, the islands were still so underdeveloped that only one battleship at a time could coal in Honolulu harbor, and Missouri and the rest of the Third Division had to refuel at Lahaina on Maui. Congress had just authorized a million dollars to develop Pearl Harbor outside Honolulu as the fleet’s main Pacific base, and Rear Admiral Seaton Schroeder and all his officers visited the site. Among those inspecting the harbor were Ensigns Harold Stark, Husband Kimmel, and William Halsey. Thirty-three years later, Kimmel would be commander of the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, when the Japanese attacked on December 7, 1941. Halsey, in command of an aircraft carrier, would be away from Pearl, and his ship would escape the general destruction. Stark would be chief of naval operations in Washington.

Most Hawaiians welcomed the American sailors with traditional warmth and hospitality, showering them with leis, but Queen Liliuokalani, who had been overthrown by American planters in 1893, refused to take part in the celebration. The sailors marveled at the beauty of the islands, the exotic appearance of the natives, and the local customs. Their letters home and newspaper reports of the visit gave most Americans their first real picture of this new American territory.

On July 22 the fleet left Honolulu for the longest leg of the trip—3,850 miles to Auckland, New Zealand. As it departed, a ship’s surgeon wrote, “Honolulu never looked prettier than it did in the evening light as we sailed away . . . we saw the lights of the town for several hours . . . and as soon as it was a little dark a good many fireworks were sent up.”

The first half of the voyage, from Norfolk to California, had been primarily a military exercise to demonstrate naval power and efficiency. The trip home was much more about diplomacy, with the fleet visiting Pacific countries important to America. At the same time, New Zealand and Australia sought American friendship, worried that waves of Japanese immigrants would soon outnumber “Europeans.” They also feared the growing power of the Japanese navy and felt they could no longer depend upon the British navy’s small Pacific Squadron. The new fleet commander, Rear Admiral Charles S. Sperry, who had replaced the ailing Admiral Evans in California, did not want to play on “yellow peril” fears. During his visit to New Zealand and Australia, he thus carefully spoke only of Anglo-American friendship and common commercial interests.

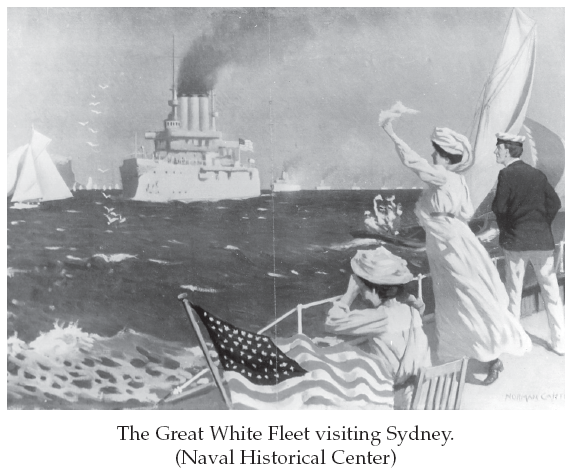

Sperry’s cautious diplomatic language did not dampen the warm welcome the fleet received when it arrived in Auckland on August 9 after more than two weeks at sea. Fully 10 percent of New Zealand’s population—100,000 people—turned out to greet it, and the whole city was decorated with flags and pictures of President Roosevelt and King Edward VII. During their week in Auckland, the sailors were enthusiastically entertained with parties, tours, and horse races. American and British sailors danced in the streets with local citizens, and the Americans bought toys and native Maori crafts and mailed home over 40,000 postcards. As part of the ceremonies honoring the fleet, sixteen oak trees were planted in Albert Park, one named for Missouri and the others for her sisters in the fleet. The Americans called New Zealanders the “healthiest, happiest, most prosperous” people in the world and New Zealanders were equally delighted with their visitors. Local newspapers proclaimed the two countries bound by “ties of blood, of religion, of origin, of ideals, of aspirations.” The country also saw the visit, however, as a demonstration “against Oriental immigration into the White Man’s Lands.”

The welcome in Australia was no less warm. In Sydney the fleet was greeted by over a half million people—more than had celebrated the founding of the Commonwealth of Australia. Twelve thousand British, American, and Australian servicemen marched in the largest military parade in Australian history. Then the southern winter turned cold, and by the end of the visit, an officer joked that “the visitor was overtired, the shows overlong, the skies overcast, and the winds overcold.”

Worn out from their reception in Sydney, the crews were not looking forward to Melbourne, where local officials were determined to put on an even bigger party for the Americans. Indeed, only seven sailors appeared for a dinner prepared for three thousand guests at the Exhibition Building. A local newspaper explained the “fiasco of the ‘Uneaten Dinner’: when every tar . . . has a girl on his arm it is easily understood that he does not want to leave the lights and the crowd [to eat dinner with his shipmates.]” At a fireworks display the next evening, there also seemed to be few sailors: “But they were there, very much so. Every rocket revealed tender scenes. Only here and there, a girl had secured the attention of a sailor boy all to herself. Most of them walked with two girls—an arm around each.”

Indeed, Melbourne turned out to be the most popular liberty port on the entire cruise, and the city treated the Americans so well that many sailors were late returning to their ships because mobs of girls hugging and kissing them blocked their way back to the docks. Over 100 deserted, with one young officer writing his parents: “If I were not in the Navy I would settle here myself. For a young man of energy there is a fortune waiting.” So many sailors were late that on Georgia 87 percent of her 850 first-class seamen were demoted in punishment.

The fleet reached the scene of Admiral Dewey’s great Manila Bay victory on October 2. Upon arrival they discovered that Manila was suffering from a cholera epidemic. All local celebrations and most shore leaves were thus cancelled, and the crews spent the whole Philippine stay coaling the ships in the blazing tropical heat and humidity. Because of the length of the voyage to Yokohama, Japan, extra coal was heaped on deck. Coaling was disrupted by a typhoon with one hundred-mile-an-hour winds on October 4, but the fleet only lost a few small boats.

The fleet left Manila on October 10, and two days later ran into a second typhoon. Even the largest modern battleships “wallowed like a herd of swine”; smaller ships were forced to slow to a crawl. Missouri’s decks were repeatedly swamped by huge waves, and the officers and men on her bridge were soaked by spray. Other ships lost boats, masts, and radio antenna, and three sailors were swept overboard. Two were rescued by following ships, but when Rhode Island, sailing at the rear of the fleet, lost a man, the crew, unable to turn or lower a rescue boat because of the storm, could only watch him “in the water looking after the ship” as they steamed away.

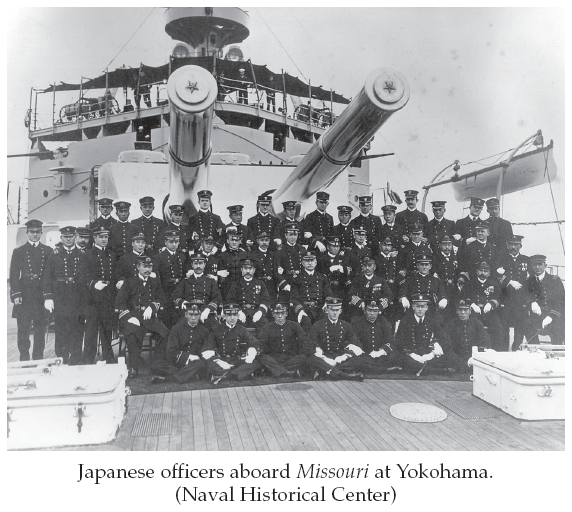

In spite of years of bitter tension between Americans and Japanese, Japan welcomed the Great White Fleet with warmth, hospitality, and careful preparation. A squadron of gray Japanese cruisers accompanied by six merchant ships with WELCOME painted on their black hulls met the fleet. The merchant ships were crowded with Japanese men, women, and children, all cheering and singing American patriotic songs in English. Thousands of Japanese schoolchildren had been taught to sing “The Star-Spangled Banner” and other songs. While the fleet was in Japan student volunteers acted as guides and interpreters for the American sailors. Admiral Sperry was equally careful to avoid offense, and his sailors were closely supervised to prevent any misbehavior while in Japan.

The high point of the visit was an audience with the Emperor on October 20 in Tokyo. The meeting went so well that the Emperor joined the state luncheon for the American commanders and “chatted amiably” through the whole meal. Three days later the Japanese navy entertained the American officers on the British-built battleship Mikasa, with Japanese admirals and captains hoisting the American admirals and ambassador on their shoulders and parading them around the decks. Next day Admiral Sperry returned the hospitality on his flagship, Connecticut, but over 3,300 Japanese guests quickly exhausted the food and drink. In contrast to Japanese lavishness, the Americans had only budgeted $1,300 to entertain their guests. As an American officer wrote: “it was as sad an affair as the Mikasa was beautiful. Oh my, oh my, Americans have a great deal to learn in polite manners.” The Japanese were polite, and the whole visit was considered a great diplomatic success. President Roosevelt wrote, “My policy of constant friendliness and courtesy toward Japan, coupled with sending the fleet around the world, has borne good results.”

Finally, on December 1, 1908, flying “homeward-bound pennants” that were two hundred feet long, the fleet left Manila for Colombo, Ceylon, and home. After a quick passage the fleet paused in Colombo to coal and marvel at the “rickshaw men, shopkeepers, tattooers, and a whole rabble of . . . people telling [us] where the most beautiful Singhalese girls could be found, very cheap.”

After more than a year away from home, the crews grew increasingly excited as they steamed through the Indian Ocean toward the Red Sea and the Suez Canal. The sailors on Illinois began planning a ball to celebrate their return to Boston, and with their band playing, practiced waltzes on the decks. In the Red Sea the battleships were given three cheers by British soldiers on a troopship bound for India. They entered the Suez Canal in early January.

When it reached the Mediterranean, the fleet divided to allow the ships to visit more ports before they reassembled at Gibraltar for the final leg home. Missouri and Ohio were first sent to Greece, where their captains were introduced to the queen and the royal family toured Missouri. After coaling, the ships visited the Turkish ports of Salonika and Smyrna to show support for a new constitutional government led by the liberal “Young Turks” party. Fifty-three years earlier, the first St. Louis had forced the Austrian navy to surrender Hungarian revolutionary Martin Koszta in Smyrna harbor. Other battleships visited France, British Malta, the Ottoman North African port of Tripoli, and French Algiers. They also stopped in Italy and Sicily to offer assistance to victims of a massive earthquake and tidal wave that had killed some 200,000 people.

The fleet gathered at Gibraltar in late January, joining British, Russian, French, and Dutch warships at anchor. Missouri arrived on February 1, some sixty-six years after the first American Missouri had burned and sunk at Gibraltar. With so many nationalities represented, the playing of national anthems and firing of salutes took over an hour. For the next week the crews loaded their ships with coal and provisions, cleaned and touched up the paint, and polished the brasswork for the trip home. Playing “God Save the King” and “Home, Sweet Home,” the fleet steamed out of Gibraltar on February 9, 1909, for the journey across the Atlantic. Five days later Admiral Sperry was able to radio his position to a naval station on Fire Island, New York, some two thousand miles ahead.

The whole fleet arrived home on February 22—Washington’s birthday—to a celebration of “patriotism of the best American type” and greetings by a delighted President Roosevelt. As he said in his toast to the fleet, “Not until an American fleet returns victorious from a great sea-fight will there be another such home-coming as this. We stay-at-homes drink to the men who have made us so proud of our country.”

The ships returned to their East Coast homeports, where the crews were finally reunited with their families and their ships were repainted in the new standard “battleship gray.” The world cruise had been a military, political, and diplomatic triumph. The fleet had proven not only the technical reliability of its ships, but also the skill, discipline, and fortitude of its officers and men. Thanks to journalists who accompanied the fleet and wrote newspaper stories read by tens of millions of readers, American and foreign audiences learned more about the strength of the American fleet and the peoples of such distant lands as Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and even Japan. Finally, the bold voyage ordered by Theodore Roosevelt sent a message of solidarity to Australia, New Zealand, and other British possessions, while warning Germany and Japan of America’s growing military power. Ironically, though, the White Fleet, which seemed so powerful to foreign crowds, was obsolete before it even left Norfolk in December of 1907.

In 1904, a brilliant naval reformer, Admiral Sir John Fisher, had become commander in chief of the British Royal Navy. Fisher ruthlessly scrapped older battleships and secretly planned the most powerful and revolutionary battleship ever seen. Designed to be faster than any other battleship, with twice as many main guns, this new Dreadnought made every other warship obsolete. Built with astonishing speed in just one year, Dreadnought began her sea trials in October 1906 as Missouri was peacefully patrolling the Caribbean. While only 4,000 tons heavier, Dreadnought was 130 feet longer, carried ten 12-inch guns to Missouri’s four, and most important, was powered by smooth 23,000-horsepower turbine engines rather than the troublesome reciprocating piston engines of earlier battleships. The turbines, which could run at top speed with little maintenance, allowed Dreadnought to outrun any other battleship in the world. Her huge “all big gun” battery of twelve-inch guns was easier to aim than the mixture of big and small caliber guns on other ships. She was thus able to fire accurately at such long range that she could catch and beat any other two or three battleships in any other navy.

Other navies frantically designed comparable “dreadnoughts.” Germany lost a year in the naval race, and it was only in 1910 that the United States fielded ships of comparable gunpower and speed. Five years after the triumphal return of the Great White Fleet, therefore, naval technology had advanced so quickly that in August 1914 none of the White Fleet was fit to join the battle line or face modern “superdreadnoughts.”

While most naval strategists and ordinary citizens focused on the powerful and glamorous battle fleets, the ordinary routine business of peacetime navies was carried out by smaller ships or “cruisers” patrolling foreign stations. The first St. Louis had a long and distinguished career, serving all over the world before retiring in Philadelphia. As Jackie Fisher was planning his revolutionary Dreadnought, another St. Louis was launched in Philadelphia. Some 30 feet longer than the battleship Missouri, she weighed 9,700 tons and had a speed of 22 knots. She carried a crew of 673 officers and men, and was armed with fourteen 6-inch guns as well as many smaller guns. This new cruiser St. Louis left for duty with the Pacific Fleet in May 1907, stopping at many of the same ports visited by the Great White Fleet seven months later.

St. Louis just missed the excitement of the fleet’s California visits because she was visiting Hawaii and Central America as the fleet sailed westward from San Francisco. While Missouri returned to serve in the Atlantic, St. Louis spent the next few years on the West Coast. When war broke out in Europe in August 1914, the United States at first tried to remain neutral, hoping to trade with all the warring powers. German agitation and sabotage in the United States, along with their aggressive submarine campaign, quickly turned many Americans against Germany. In February 1915 Germany announced unrestricted submarine warfare around England, and in May 1915 sank the British liner Lusitania with great loss of life.

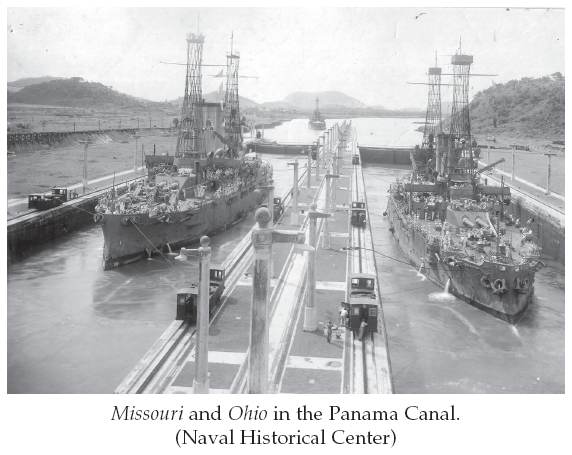

As the U.S. Navy made war plans, even older battleships like Missouri were valuable to train new sailors. In the summer of 1915 Missouri carried Naval Academy midshipmen on a training cruise through the Caribbean and Pacific. She and Ohio became the first battleships to pass through the new Panama Canal. A cadet described the tropical jungles, huge locks that swallowed the battleships, freshwater lakes, and deep cuts as the ships steamed toward the Pacific. On the transit, Missouri carried the U.S. Army’s Canal Zone governor, his staff, and “lots of good looking [ladies]” and was cheered by U.S. Army troops as they passed. “We gave several [navy] yells and the ‘Star-Spangled Banner’ . . . for it was a great occasion—the passing of the first battleship through the canal.”

Missouri then went to the reserves, but cruiser St. Louis was assigned to Pearl Harbor. As Pearl Harbor’s “station ship,” she was responsible for watching the German gunboat Geier which had been interned in Honolulu since the outbreak of war in 1914. According to St. Louis’s “War Log,” the Geier stayed in contact with German secret agents in the islands as well as with the German Pacific Squadron. In February 1917, Geier’s crew tried to burn their ship to damage Honolulu’s port. Supported by army troops and cannon, a party from St. Louis boarded the burning ship and took the German crew prisoner. They discovered that the Germans had sabotaged the magazine and set the boiler afire in hopes of causing a larger and even more damaging explosion. St. Louis sailors towed the burning ship to a safer location and battled the blaze all day until relieved.

Within two months, St. Louis, Missouri, and even the Spanish-American War auxiliary passenger ship St. Louis, were all called to wartime duty as the United States entered World War I in April 1917. In March, the liner St. Louis was armed with three six-inch guns manned by twenty-six U.S. Navy sailors to protect her as she continued passenger service between New York and Liverpool, England. On May 30 in the Irish Channel she ran over a submarine that had fired a torpedo at her, and in July she exchanged cannon fire with a surfaced U-boat. Missouri rejoined the Atlantic Fleet as a division flagship and training ship. During the war she remained in the Chesapeake Bay area training thousands of recruits in gunnery and engineering skills.

Cruiser St. Louis left Pearl Harbor in early April, picked up 500 naval volunteers in San Diego to bring her up to wartime strength of 823 officers and men, and reported to Philadelphia for convoy duty. Beginning in June 1917, she escorted 7 convoys across the Atlantic, logging over 100,000 miles through the bitter North Atlantic winter storms of 1917–1918. In April 1918 passenger liner St. Louis was taken over by the U.S. Navy as a troop transport and renamed Louisville. During the war the navy’s main duty was to move two million American troops and their supplies to France, and when the war ended on November 11, 1918, its happy duty was to bring the boys home.

Even Missouri was pressed into this service, making four round trips to Brest, France, to bring 3,278 soldiers back to America. St. Louis made seven trips, bringing home 8,400 soldiers, and Louisville made six trips ferrying soldiers. In September 1919 Louisville was returned to her civilian owners, who changed her name back to St. Louis. She caught fire in January 1920 while being reconditioned for passenger service and was so badly damaged that she was scrapped.

Cruiser St. Louis, now designated CA-18, was assigned to the European Squadron and in October 1920 reported to Constantinople, Turkey, where the first St. Louis had patrolled seventy years earlier. War and revolution still troubled the eastern Mediterranean, and St. Louis went to Yalta and Sevastopol to pick up refugees fleeing the Russian civil war. Revolution also broke out in Turkey, and sailors from St. Louis helped distribute food and other humanitarian aid to Russian and Turkish refugees in Constantinople. She returned to Philadelphia and was decommissioned in March 1922. Missouri was also decommissioned in Philadelphia.

At the end of the terrible World War, many people shared President Woodrow Wilson’s dream that future wars could be avoided through international cooperation. To reduce the fleets to the size agreed to in postwar treaties, countries scrapped many of their older battleships. Among these ships were Missouri and many of her sisters from the Great White Fleet.