CHAPTER FOUR

Another St. Louis and the Last Missouri

The Second World War

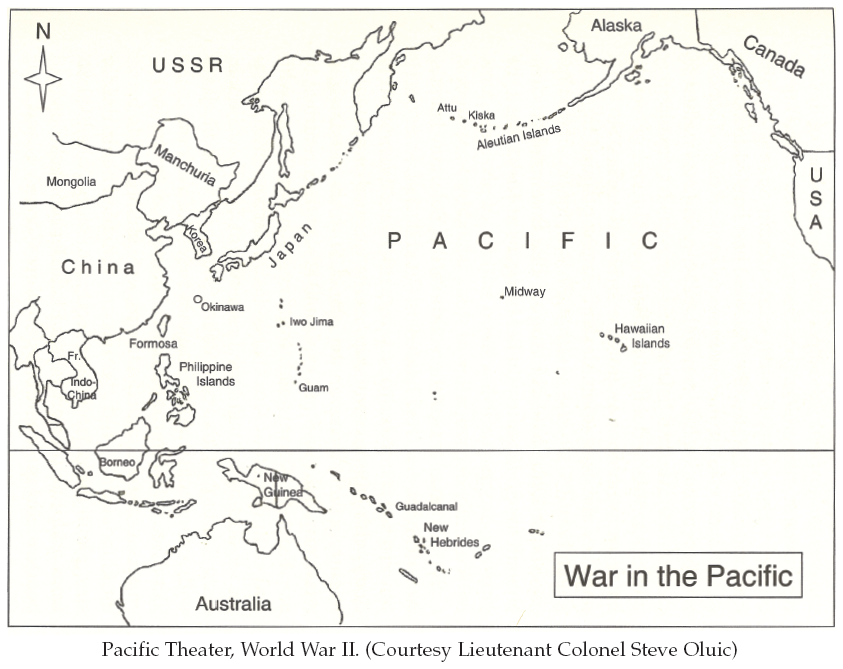

While many warships from the First World War were scrapped, three of Missouri’s White Fleet sisters suffered a more modern fate. Alabama, Virginia, and New Jersey were all destroyed by experimental aerial bombing, with Virginia and New Jersey being sunk by General Billy Mitchell’s army bombers in September 1923. Mitchell argued that modern airplanes made battleships obsolete, and the American, British, and Japanese navies converted some half-finished battleships and battlecruisers into aircraft carriers. America’s first two big, fast aircraft carriers, Lexington and Saratoga, joined the fleet in 1927. They carried seventy-five planes each and were ten knots faster, and just as heavy, as the last World War I–era battleship.

In the years after the Great War, both Japanese and American naval thinkers believed that their battle plans should be designed to fight each other for control of the Pacific Ocean. The “gun club” of battleship admirals still believed that battleships were the ultimate weapon of naval superiority, and in 1924, the chief of naval operations, Admiral Edward Eberle, predicted “the battleship of the future . . . will not be subject to fatal damage from the air.” In 1932, however, Saratoga and Lexington, with 152 planes, surprised Pearl Harbor with a dawn raid that would have devastated the naval base.

In the 1930s, the Great Depression threw millions out of work, and in Germany and Japan nationalists and militarists played on the people’s poverty and anger and built up their armies and navies to support their imperial ambitions. In 1936 the U.S. Navy had only 19 light cruisers with 6-inch guns, but President Franklin Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act jobs program included money for new light cruisers.

These new cruisers were actually almost as heavy as the Great White Fleet’s Missouri, weighing 10,000 tons and carrying main batteries of fifteen 6-inch guns in 5 triple turrets. They were powerful enough to fight Japanese heavy cruisers. Six hundred feet long, they had a top speed of 37 miles per hour thanks to 100,000-horsepower steam turbines, could steam 7,800 miles, and carried wartime crews of 1,200 men. They were the first light cruisers to carry hangars for scout seaplanes and had two catapults to launch the planes. Each ship cost some $18 million. In December 1936 work began at Newport News shipyard on a new St. Louis, CL-49. Commissioned in May 1939, St. Louis was initially stationed in Norfolk, with a native of St. Louis, Captain Charles H. Morrison, as commander.

When Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, President Roosevelt declared a “limited emergency” and raised the number of sailors in the navy to 191,000. In October St. Louis joined the American “neutrality patrol” watching the Atlantic and Caribbean from Newfoundland to Trinidad and guarding British convoys against Germany’s small and unprepared U-boat fleet.

After the fall of France in the spring of 1940 Congress voted four billion dollars to build a two-ocean navy. Navy planners had designs ready for powerful new classes of battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and aircraft carriers. But as Admiral Harold Stark, Chief of Naval Operations, pointed out, “dollars cannot buy yesterday,” and new ships took years to build. In August 1940, one of President Roosevelt’s advisors warned “it is as clear as anything on this earth that the United States will not go to war, but it is equally clear that war is coming to [America].” American naval commanders focused on the battle of the Atlantic, and in September and October, St. Louis carried a team of inspectors on a two-month visit to possible naval and air bases from Newfoundland to Bermuda, the Bahamas, Jamaica, St. Lucia, Antigua, Trinidad, and British Guiana (now Belize) on the coast of South America.

As the war came closer to America, St. Louis moved to the Pacific Ocean, where she patrolled around the Hawaiian Islands. On December 1, 1941, as Japan’s six largest aircraft carriers steamed toward Pearl Harbor, the Japanese combined fleet was more powerful and better trained than the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Japan had ten battleships to America’s nine World War I–vintage ships—many of them “old enough to vote.” Eight U.S. battleships were at Pearl Harbor. To Japan’s ten aircraft carriers, the Pacific Fleet had only three. Fortunately, all three were away from Pearl. Rear Admiral William “Bull” Halsey was with Enterprise carrying fighter planes to Wake Island. Japan had 18 heavy and 17 light cruisers, while the United States had 13 heavies and 11 light cruisers—a number of them away from Pearl with the carriers or on patrol.

When the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor on Sunday morning, December 7, they found eight battleships, two heavy cruisers, six light cruisers, and twenty-nine destroyers lying in the harbor with cold boilers and empty guns. Many officers and men were on shore leave, and those aboard ship were beginning another quiet peacetime Sunday morning. Two of St. Louis’s boilers were disassembled, and workers had cut a four-foot hole in the side of the ship to make repairs easier. According to Captain George Rood’s report, his crew immediately opened fire on the first wave of attacking torpedo bombers. Men at the larger five-inch turrets also quickly began shooting at high-alti-tude bombers. Because the electrical system was under repair, the gunners had to load and fire by hand. The engineers lit the boilers, sealed the hole in the ship’s side, and began trying to get under way to escape the death trap of Pearl Harbor.

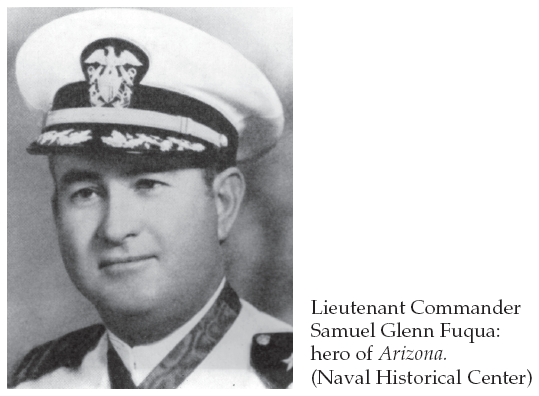

The Japanese concentrated their fire on the helpless battleships. Arizona was struck by aerial bombs, which exploded her magazine and killed her captain and admiral. One of Arizona’s officers, Lieutenant Commander Samuel Fuqua of Laddonia, Missouri, was stunned by the explosion of a Japanese bomb. When he regained consciousness he led the crew in fighting fires and rescuing wounded shipmates in the face of continued enemy attacks. He rallied the crew:

in such an amazingly calm and cool manner and with such excellent judgment that it inspired everyone who saw him and undoubtedly resulted in the saving of many lives. After realizing that the ship could not be saved and that he was the senior surviving officer, he . . . directed abandoning ship and rescue of personnel until satisfied that all . . . that could be had been saved, after which he left his ship.

For his heroism Fuqua was awarded the Medal of Honor. Although 1,103 out of a crew of 1,400 were lost, he managed to save some of his men.

Only one battleship was able to get under way. The crew of Nevada, the oldest battleship at Pearl, were raising the American flag and playing “The Star-Spangled Banner” when Japanese planes attacked. The flag was ripped by gunfire, but the band completed the national anthem before the crew returned fire and began trying to escape the harbor. Hit by several bombs and a torpedo that tore a huge hole in her side, Nevada still managed to shoot down some attacking planes and get free of the mooring without the help of tugboats. “Down the ship channel she [went], fighting off dive bombers who concentrated on her, at one time surrounded by a curtain of smoke and spray so dense that spectators thought her gone; but most of the bombs were near misses. [Nevada was] a proud and gallant sight.”

St. Louis reported shooting down two or three Japanese planes, and Captain Rood was finally able to back his ship out into the harbor ninety minutes after the first attack. Quickly picking up speed in the chaotic harbor, St. Louis rammed and broke a steel cable tying a dredge to the dock. Seeing that some destroyers and St. Louis were trying to reach the ocean, and fearing that Nevada might sink and block the channel, her officers ran her aground and she settled to the bottom. By now moving at twenty-eight miles per hour, St. Louis saw a submarine fire two torpedoes at her. Fortunately both hit a reef and exploded harmlessly. St. Louis returned fire and steamed out to sea, where Captain Rood gathered some destroyers into an attack group and went hunting the Japanese aircraft carriers that were reported to still be in the area. In fact, the carriers were hundreds of miles north of Pearl Harbor steaming toward Japan at top speed. St. Louis had left her four scout planes at Ford Island naval base when she raced to sea, but during the attack two of them managed to take off without their gunners. Although unarmed, the pilots tried to distract the Japanese bombers from the defenseless ships and port facilities. St. Louis and the destroyers searched for the Japanese carriers for three days before returning to the shattered Pacific Fleet. During the attack St. Louis had fired some sixteen thousand rounds of ammunition and possibly destroyed three enemy planes and a miniature submarine. Because she suffered no casualties and was only hit by a few Japanese bullets, her crew began calling her “Lucky Lou.” To bring her up to wartime strength, about one hundred crewmen from the damaged Nevada were transferred to St. Louis. Captain Rood reported: “the whole ship performed to a degree of perfection that exceeded my most optimistic anticipation. [I have] the highest praise . . . for their conduct, devotion to duty, willingness and coolness under fire and during the following days of most exhausting operations. . . . This fine enthusiasm and spirit continues undiminished.”

In just two hours the U.S. Navy had suffered three times as many casualties as during the entire Spanish-American and First World Wars.

When the St. Louis returned to Pearl Harbor, she was assigned to escort shiploads of wounded back to California. She then convoyed fresh troops back to Hawaii. Admiral Chester Nimitz, new commander of the Pacific Fleet, was already planning a counterattack against the Japanese. Admiral “Bull” Halsey volunteered to lead the attack, and St. Louis protected carrier Yorktown during air attacks on Japanese bases in the Marshall Islands in early February.

With so few warships available to fight the Japanese in the vast Pacific, St. Louis spent the first months of the war racing from task to task. In February 1942 she returned to Pearl Harbor to again escort convoys between Hawaii and California. She then returned to the New Hebrides Islands near New Guinea and Australia. By now Philippine president Manuel Quezon, having given General Douglas MacArthur a personal gift of a half million dollars to thank him for his attempt to defend the Philippines, had fled into exile. St. Louis escorted the passenger liner President Coolidge carrying President Quezon, which raced to San Francisco at top speed to outrun any Japanese submarines. St. Louis and President Coolidge arrived on May 8, 1942.

The very next day St. Louis steamed back toward Pearl Harbor to join a convoy taking marines and warplanes to reinforce the little American garrison on Midway Island. The convoy arrived on May 25. Brilliant American intelligence had broken the Japanese naval codes, and the navy knew that the Japanese were planning to attack Midway. Just a few days after St. Louis’s departure, on June 4, American carriers surprised the Japanese and sank four of the six big Japanese carriers that had been involved in the attack on Pearl Harbor six months earlier. In an attempt to distract the United States, the Japanese had landed troops on Kiska and Attu in the Aleutian Islands. After dropping reinforcements on Midway in late May, St. Louis rushed to defend the Alaskan islands. For the next two months, while Japanese and Allied soldiers were locked in bloody battle in the mountain jungles of New Guinea, St. Louis patrolled the dangerous Alaskan waters, plagued by thick fog and terrible storms, searching in vain for Japanese supply ships. Only in early August did the weather clear enough for St. Louis to aim her big guns at Kiska, shell the Japanese troops with her main battery of six-inch guns, and cover the reoccupation of Adak Island by army troops.

By this time, far to the south in the Solomon Islands, American marines had landed on Guadalcanal, and American cruisers and destroyers were fighting bloody night duels with Japanese warships as the two navies struggled to supply their forces on the island. St. Louis remained in Alaska until the end of October 1942 and then returned to San Francisco for a quick overhaul. Captain Rood, who had commanded St. Louis since Pearl Harbor, left the ship for his next assignment while she was at San Francisco. In early December Captain Colin Campbell took St. Louis with a convoy of troop transports to New Caledonia in the Coral Sea between the Solomon Islands and Australia.

Japanese and American troops were still locked in battle on Guadalcanal, and the navies continued their deadly struggle in the surrounding waters. In early July 1943 St. Louis and the other cruisers and carriers of Task Force 18 bombarded Japanese troops on New Georgia Island near Guadalcanal to support American landings. On the pitch-black night of July 5–6, St. Louis and the other Allied ships caught Japanese destroyers rushing reinforcements to New Georgia. St. Louis was hit by an enemy torpedo that failed to explode, confirming her crew’s opinion that she was “Lucky Lou.” Captain Campbell later received the Navy Cross for his actions. A week later, Task Force 18 again met a Japanese force at the Battle of Kolombangara. In this battle, St. Louis was again hit by a torpedo, and this time she was not so lucky. It blew a large hole in her bow but caused no serious casualties. Captain Campbell’s leadership in this action earned him the Silver Star, and St. Louis earned another trip to San Francisco for repairs.

While the ship was in California, Captain Campbell was replaced by Captain R. H. Roberts, who took St. Louis back to the Solomons in mid-November to support marine landings and bombard Japanese soldiers on Bougainville and the Green Islands. On the evening of February 14, 1944, St. Louis was attacked by six Japanese carrier bombers. After five near misses, she was hit in a crew compartment by a bomb that killed twenty-three sailors and wounded twenty. Both her airplanes were crippled, and the fire drove the crew from her rear engine room. After another air attack, St. Louis withdrew while her crew repaired the damage.

In June, during the landings on Saipan, Guam, and Tinian, St. Louis stayed close to shore using her main six-inch guns to shell Japanese defenders. On July 7, a propeller shaft weakened by her earlier battles and close calls broke free, but St. Louis remained on station for three more weeks before again returning to California for overhaul.

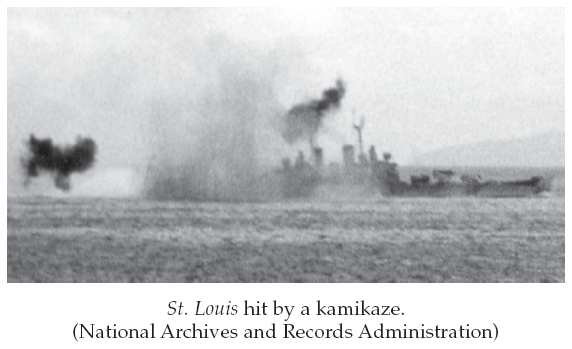

By the time St. Louis returned to the South Pacific in mid-November, General Douglas MacArthur’s Sixth U.S. Army had returned to Leyte Island in the Philippines, and one of the greatest air and naval battles of World War II had been raging for a month. In the Battle of Leyte Gulf the Japanese lost hundreds of warplanes, almost all their remaining skilled pilots, all four of their carriers, and three battleships. The land battle for the Philippines continued, but the Japanese fleet and air force were so weakened that they had only one strategy left. That strategy came into action just as St. Louis arrived back in Leyte Gulf. With their skilled pilots dead, and facing increasingly heavy and effective naval antiaircraft gunfire, the Japanese turned to suicide air attacks by kamikaze pilots who tried to crash their bomb-laden aircraft into American ships.

In her first two weeks off Leyte St. Louis beat back thirty-three air attacks. On November 27, 1944, she was again attacked by swarms of Japanese planes. After fighting off the first wave of a dozen attackers, St. Louis was immediately threatened by another ten bombers. Although hit and afire, one bomber crashed into St. Louis’s hangar and exploded on impact.

Several gun crews were killed, and fires broke out, but St. Louis continued to fight and dodge at top speed. She avoided two more burning Japanese planes in the next few minutes, but a third crashed into the sea so close that St. Louis lost twenty feet of her armor belt and began flooding. For two hours, while gunners shot down another kamikaze and St. Louis fought off torpedo attacks, the crew struggled to control the flooding, fight the fires, and treat the wounded. In all, the ship lost fifteen dead, one missing, twenty-one seriously wounded, and another twenty-two lightly wounded. According to her Navy Unit Commendation: “Constantly harassed by hostile suicide attackers . . . she rendered invaluable fire support to our assault forces and, although severely damaged . . . during one of the most vicious multiple kamikaze attacks of the war, continued in action after decisively routing the enemy with heavy casualties.”

Captain Ralph Roberts was awarded the Legion of Merit, with his executive officer, a marine captain, and a sailor earning Silver Stars. Four others earned Bronze Stars. One of the wounded who earned the Purple Heart was a Gunner’s Mate Brickner of Boonville, Missouri.

After a quick trip to California for repairs, St. Louis rejoined the American carriers attacking the Japanese home islands in late March 1945. By now, the United States had recaptured the Philippines and had won Iwo Jima, but at the cost of almost seven thousand dead and twenty thousand wounded. During this battle the marines earned twenty-seven Medals of Honor, including one for Sergeant Darrell Cole of Flat River, Missouri. Almost all twenty-one thousand Japanese defenders fought to the death. The American forces attacking Iwo Jima were supported by a huge American battle fleet, which included both the oldest U.S. battleship—Arkansas—and the newest—Missouri.

Missouri, BB-63, was the last American battleship ever completed. She and her sisters, Iowa, New Jersey, and Wisconsin, represented the evolution of over two hundred years of naval strategic thinking, but by the time they entered the battle against Japan in the last months of the Second World War, military technology had passed them by. Designed during the great naval race of the 1930s between democratic England and America and totalitarian Germany and Japan, they were created to be the fastest, best protected, and most heavily armed ships possible. They were narrow enough to pass through the Panama Canal and fast enough to outrun any other battleship, which was essential to their most important wartime duty—protecting fast American aircraft carriers from Japanese air attack. While twentieth-century battleship design had always concentrated on the size and power of main guns, the Iowas were covered with twenty five-inch guns and over a hundred smaller antiaircraft guns to defeat the swarms of Japanese fighters and bombers intent on sinking U.S. carriers.

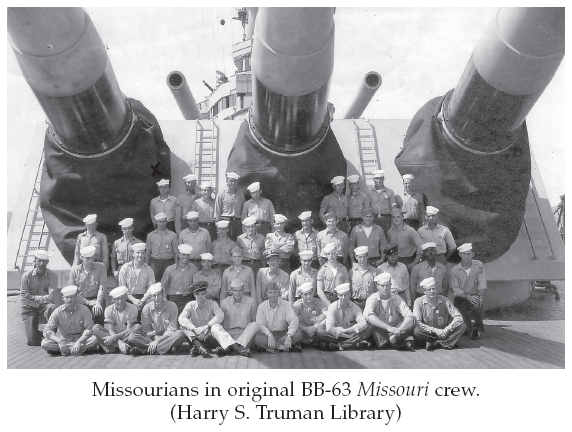

Work on Iowa began at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in June 1940, and on January 6, 1941, the yard began building Missouri. After an unusually long construction time of three years, while higher priority carriers, submarines, destroyers, and light cruisers were hastily built, Missouri was finally launched on January 29, 1944. Ignoring Missouri’s republican governor Forrest C. Donnel, President Roosevelt chose to honor the powerful democratic chairman of the congressional war production board investigating committee by asking Harry Truman’s daughter, Margaret, to christen the newest battleship. Before an audience of over 20,000, including a live television audience at the General Electric propulsion plant in Schenectady, New York, which had built her huge 212,000-horsepower turbines, Senator Truman predicted: “The time will surely come when the people of Missouri will thrill with pride as the Missouri and her sister ships . . . sail into Tokyo Bay.” By radio, Admiral Halsey added: “We have a date to keep in Tokyo. Ships like Missouri will provide the wallop to flatten Tojo and his crew.” Margaret Truman then christened Missouri with a bottle of champagne made from Missouri grapes.

Although final construction took another six months, Senator Truman was bombarded by letters from Missourians asking for assignment to the ship. Most of the wartime crew of 2,700 officers and men were from new draftees from the East, with only a handful from the “Show-Me” state, but Harry’s nephew John C. Truman, a thirty-one-year-old schoolteacher from Independence with three children, happened to be randomly assigned to Missouri.

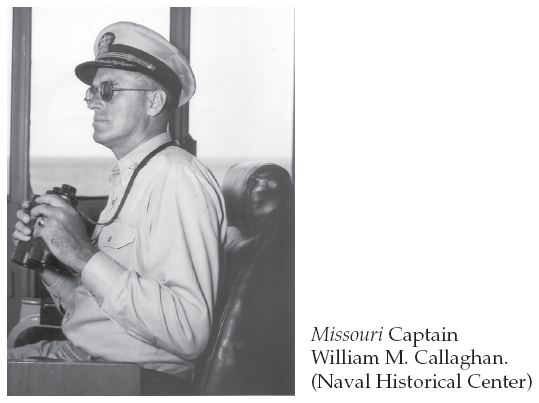

Missouri was finally commissioned on June 11, 1944, five days after the Allied invasion of Normandy, and two months after Wisconsin, BB-64, joined the fleet. Missouri was the last of fifty-seven battleships in the U.S. Navy. Her first captain, William M. Callaghan, had participated in a training cruise aboard the Great White Fleet Missouri while a young Annapolis midshipman.

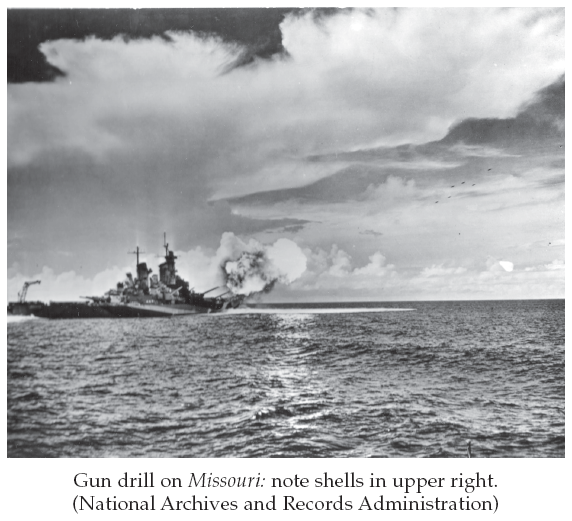

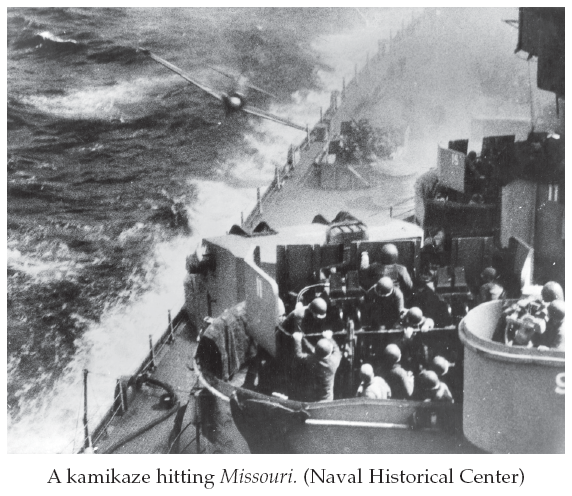

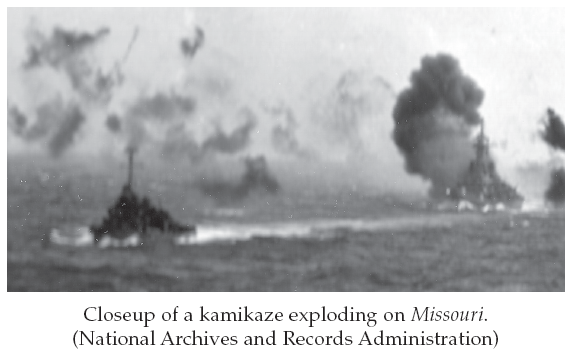

After a few months of training for her green crew and testing of her guns, engines, and other systems, Missouri squeezed through the Panama Canal on November 18, 1944, and reached the American naval base at Ulithi in the Caroline Islands east of Leyte, Philippines, in mid-January. There she joined Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher’s aircraft carriers as on February 16, 1945, they launched the first carrier air attacks on Japan since Jimmy Doolittle’s 1942 Tokyo raid. On the same day a huge American fleet began bombarding Iwo Jima. Missouri and her carriers remained well offshore, with the battleship using her radar-controlled five-inch guns to beat off attacking Japanese airplanes. Steaming steadily and constantly alert, Missouri traveled over eight thousand miles in February alone. Missouri and St. Louis screened the American carriers attacking the Japanese home islands and acted as “armored oilers,” repeatedly refueling their thirsty short-range destroyer escorts. Joined by her sisters New Jersey and Wisconsin, Missouri shelled Okinawa in late March with her sixteen-inch main batteries from twenty thousand yards offshore. In early April, a kamikaze aircraft carrying a five hundred-pound bomb penetrated Missouri’s wall of defensive fire. One of sixteen aircraft launched from a base in southern Japan, the plane hit the side of the battleship just below the open gunmounts on the main deck, exploding with a huge and spectacular cloud of black smoke.

Fortunately the bomb fell into the ocean without detonating. A wing and the body of the pilot, probably nineteen-year-old Setsuo Ishino, landed on the deck. In the heat of the battle the crew began to throw the body overboard, but Captain Callaghan, who had lost a brother to the Japanese, ordered his crew to give the pilot a proper burial at sea. Captain Callaghan never mentioned the episode again, but fifty-six years later American veterans identified the Japanese pilots involved and invited the survivors to a ceremony aboard Missouri at Pearl Harbor on April 12, 2001, to honor Callaghan’s chivalry. Two days after the kamikaze hit Missouri, President Franklin Roosevelt died and his new vice president, Harry Truman, became the thirty-third president.

Heavy attacks continued around the clock, and during the Okinawa campaign the navy suffered 4,900 killed and 4,800 wounded. Both Missouri and St. Louis dodged close calls while all around them some 200 ships were hit, and, of those, 34 sank. The crews worked under terrible strain for weeks on end, with men and equipment suffering from the constant danger and action as the Japanese carried out 1,900 suicide attacks. Missouri shot down 5 enemy planes and helped to destroy 6 others, and St. Louis destroyed 4 and helped shoot down another 4. Captain John Griggs of St. Louis won the Silver Star for commanding the cruiser during the Okinawa battle.

In early June, the fleet was hit by an eighty-mile-an-hour typhoon with one hundred-foot waves, which tore one hundred feet off the bow of the new heavy cruiser Pittsburgh. According to a Missouri sailor, the battleship, even though three times heavier than Pittsburgh: “wallowed around . . . like a ping-pong ball in a bathtub with a baby playing with it” but suffered no serious damage.

In mid-July, Missouri, Iowa, and Wisconsin shelled steel mills in Hokkaido from over fifteen miles offshore, and hit other targets on following days with 2,700 pound shells from their main guns. The bombardment was so terrifying that most civilians fled and many workers refused to return to their posts. By now, American ships and planes could operate freely around the Japanese islands, but the military government still refused to surrender. To end the war Truman ordered the use of a new weapon, and on August 6, 1945, an army B-29 bomber dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Three days later a second bomb hit Nagasaki, and the Japanese emperor told his supreme war council to accept Allied surrender terms.

On August 15, the emperor broadcast a surrender order to the Japanese people and military, and President Truman announced the end of the war. In celebration, Admiral Halsey ordered the crew to blow Missouri’s steam whistle, which jammed open until engineers could disconnect the steam line. The next day British Pacific Fleet commander Sir Bruce Fraser came aboard and awarded Halsey a knighthood of the British Empire. Two hundred Missouri sailors were given shore duty as part of the initial American military force occupying the Japanese islands. American newspapers began reporting that the formal Japanese surrender would take place on Missouri in Tokyo Bay, but even Missouri’s new captain, Stuart “Sunshine” Murray, only learned of the honor when his wife complained in a letter, “why don’t you tell me about these things instead of letting me read it in the newspapers?”

Beneath their joy and relief at the end of the war, the Allies were concerned that diehard Japanese might launch further suicide attacks. Halsey ordered his forces to shoot down any Japanese intruders “in a friendly sort of way.” Japanese harbor pilots came aboard Missouri under tight guard to show her officers the safe way into Tokyo Bay, and the Americans insisted a Japanese destroyer lead Allied battleships Missouri, Iowa, and Duke of York into the bay on August 29 as the crew stood by their guns on full alert against possible Japanese treachery. In preparation for the historic ceremony, the U.S. Naval Academy sent the flag flown by Commodore Matthew Perry’s flagship, Mississippi, during her visit to Tokyo in 1853. Too fragile to be flown, the flag was displayed while by some accounts Missouri flew the flag that had flown over the U.S. Capitol on December 7, 1941.

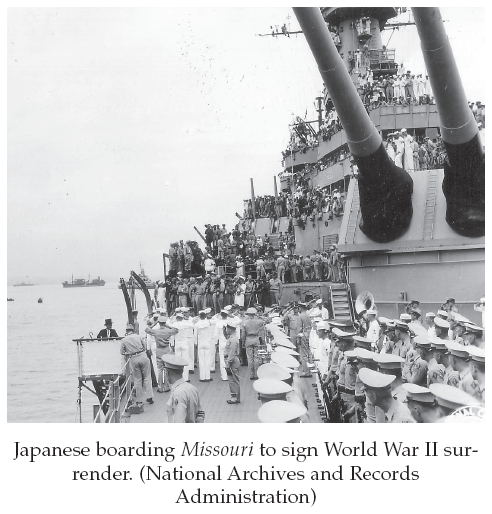

On the morning of September 2, 1945, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur and Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz came aboard Missouri to receive the Japanese surrender. The ship was crowded with crewmen, Allies, including former prisoners of war, and hundreds of journalists and photographers. One of the defeated Japanese remembered: “A million eyes seemed to beat on us with the million shafts of a storm of arrows barbed with fire. I felt them sink into my body with a sharp physical pain. Never have I realized that staring eyes could hurt so much.”

At the end of the brief surrender ceremony, which was broadcast live around the world, General MacArthur concluded: “Let us pray that peace be now restored to the world and that God will preserve it always. Your sons and daughters have served you well and faithfully . . . they are homeward bound.”

The ceremony was followed by a flyover by a massive fleet of hundreds of navy carrier planes and army B-29 bombers.

As MacArthur had promised, for most of the navy the first order of business was getting the troops home. The crew celebrated the surrender with a turkey dinner, welcome after months of monotonous and skimpy battle rations, then Missouri left Tokyo Bay on September 6 and picked up fifteen hundred marines on Guam for the happy journey home. The already crowded wartime crew was even more cramped with the additional passengers, and the officers tried to keep the men entertained with movies, boxing matches, and other contests as they rode the “Magic Carpet” home. The war was not over for everybody, however, and the weary veteran St. Louis stayed on station off the China coast as flagship of the Yangtze River Patrol Force. In October the cruiser finally joined Operation Magic Carpet, carrying eight hundred troops back to San Francisco on the first of three passenger runs that kept her disappointed crew on duty through the Christmas holidays. St. Louis had fought the Pacific war from the first minute to the last, earning eleven Battle Stars for her service. As her Navy Unit Citation said: “A resolute and sturdy veteran, complemented by skilled and aggressive officers and men, St. Louis rendered distinctive service, sustaining and enhancing the finest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

St. Louis finally reached Philadelphia in February 1946, and was decommissioned in June. In 1951 she was sold to the Brazilian navy, where she served as Almirante Tamandare until 1977. The Brazilians then donated the ship’s wheel, battle flags, and builder’s plaque to former crewmen and residents of St. Louis who wished to preserve her memory. After an unsuccessful American fund-raising effort to “save the ‘Lucky Lou’” as a war memorial, the Brazilians sold her to a Hong Kong scrap dealer. On August 24, 1980, while being towed around the Cape of Good Hope, she capsized and sank.