CHAPTER FIVE

The Cold War

World War II ended as the Great War had ended twenty-seven years earlier, with relief, joy, demobilization of the great armies and navies, and the hope for a peaceful future. Harry Truman was proud of the battleship christened by his daughter and named for his state, and even more proud that after the Japanese surrender Missouri was the most famous battleship in the world. Missouri was thus the star attraction of a great naval review and victory celebration in New York at the end of October. To the president’s disappointment, however, his nephew John and some 30 percent of the crew left the ship in Norfolk to return to civilian life. After workmen installed a plaque on the deck to mark the spot on which the surrender had taken place, the ship sailed up the East Coast to New York. On October 27, after a triumphal parade through the streets of the city, President Truman, his daughter, Margaret, and New York governor Thomas Dewey toured the ship. Sitting at the Tokyo Bay surrender table and signing Missouri’s guest book, Truman declared this the happiest day of his life. He then announced the bar open and drank a glass of bourbon with Captain Murray before reviewing the great fleet at anchor in the Hudson River.

During the ten-day celebration, some 750,000 New Yorkers toured the ship, leaving graffiti everywhere and stealing souvenirs. Someone even reached through a porthole and stole Captain Murray’s uniform hat off his desk. As a junior officer said, some visitors “just wanted to grub and grab.” After coping with the horde of visitors, the crew got a rest as Missouri returned to her birthplace at the Brooklyn Navy Yard for an overhaul. Captain Murray was succeeded by St. Louis native Roscoe Hillenkoetter. The 1919 Annapolis graduate had served at sea in destroyers, cruisers, and battleships and as naval attaché at the American embassy in Paris. He had been in France when the Germans captured Paris in 1940, and in 1941 had been assigned as executive officer of battleship West Virginia at Pearl Harbor. West Virginia’s captain was killed in the attack on December 7, and Hillenkoetter was wounded, but he kept the ship from capsizing as she sank. African American cook Doris Miller won fame and the Navy Cross for courage during the attack. Aside from his diplomatic skill and courage under fire, Captain Hillenkoetter showed his character and integrity as a leader when the St. Joseph Lead Company of Flat River, Missouri, offered Missouri a silver sculpture of the state seal in January 1946. Hillenkoetter led a delegation of crewmen made up of Missourians to receive the gift from governor Phil M. Donnelly. While in St. Louis, a civic group honored the crew at a party at the elegant Chase Hotel. Learning that one crewman was black, the hotel refused him entrance, until Hillenkoetter, probably remembering “Dorie” Miller at Pearl Harbor, insisted: “he’s a member of the crew of Missouri. If he doesn’t come, we don’t come.”

In the spring of 1946 Hillenkoetter took on another ceremonial mission of great diplomatic importance. The United States emerged from the Second World War with the largest, most efficient, most powerful navy and air force in the world. The ally with the largest army, the Soviet Union, had conquered Eastern Europe and Berlin but was ruled by the paranoid and suspicious dictator Joseph Stalin and a ruthless and aggressive communist party. In China and Korea, communist armies were seizing territory vacated by the retreating Japanese, and in Eastern Europe small groups of communists were taking control of the countries overrun by Soviet armies. Anxious to put the burden of war behind them, few Americans recognized the growing Soviet threat. In his famous “Iron Curtain” speech in Fulton, Missouri, on March 5, 1946, Winston Churchill warned that democracy in Greece was threatened by a civil war between communists and nationalists. Greece was strategically important to the British because of its proximity to the Suez Canal through which England’s oil supplies passed. The U.S. Navy had already decided to show American military strength in the area by dispatching the battleship Missouri on a diplomatic mission to Istanbul. Hearing that Missouri would be passing Gibraltar on her way to Turkey, the American consul there wrote a letter reminding the navy of the first Missouri’s fate. The Turks were delighted at the visit by the famous battleship, even refurbishing Istanbul’s red-light district to welcome the American sailors. The Turks also gave a lavish party for the officers during which belly dancers performed to the “Missouri Waltz.” As an officer recalled: “All of us were just sitting there dying because we couldn’t break out laughing.”

The presence of Missouri encouraged the Turks to resist Soviet demands. The ship then visited Piraeus, Greece, reminding the communist rebels that American naval power could reach even around the Iron Curtain. In demonstrating the long reach of American power, Missouri was following the first modern battleship Missouri, which had entertained the Greek royal family during the visit of the Great White Fleet in 1909. Thanks in large measure to President Truman’s strong support for Greek independence, the communists were defeated, and Greece remained the only nation in Eastern Europe free of Russian control.

Missouri impressed the Greeks and Turks (and Russians) as a powerful symbol of American military strength, but in spite of the growing tension between the West and the Soviet Union, the U.S. Navy was shrinking rapidly. Two thousand ships were put into reserve, and seven thousand scrapped or given to allies such as Brazil. Navy personnel strength dropped from 3,400,000 in 1945 to 380,000 in 1950. By then, the navy had only eleven carriers and one battleship—Missouri—and even Missouri’s crew was only one-third her wartime strength. With only 800 men, her captain had barely enough crew members to keep her running.

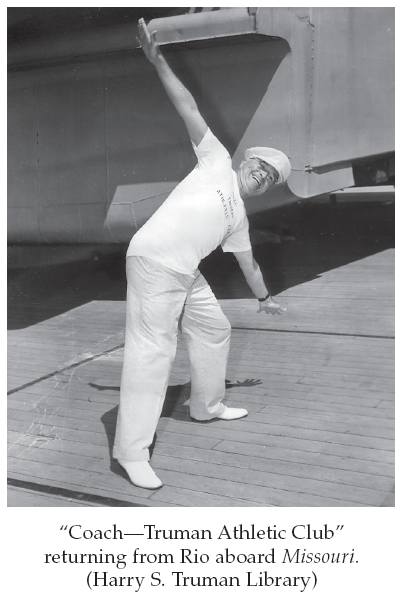

Still, Missouri was President Truman’s favorite, and in the summer of 1947 sailed to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, as the U.S. and Latin American countries signed a mutual defense treaty. President Truman flew to Rio to sign the treaty, but on September 7, he boarded Missouri with wife, Bess, and daughter, Margaret, for the cruise back to Norfolk. Truman had a wonderful time, leading exercise classes in his “Coach—Truman Athletic Club” T-shirt, chatting with sailors about baseball during his morning walks around the deck, waiting in line in the dining halls, and even joining the “victims” when the battleship crossed the equator.

New sailors had undergone the same initiation on the Great White Fleet Missouri forty years earlier, and King Neptune now accused Truman of the terrible offense of using a “despicable and unnatural means of travel” by flying to Rio for the conference. Truman was required to bribe the court with cigars, and Margaret had to sing “Anchors Aweigh” with six new ensigns. During the cruise Margaret ate with the crew, and teased captain Robert Dennison, maintaining that Missouri was her ship rather than his because she had christened it, and that she knew more about the crew than he did because she ate with them. Whether or not the crew enjoyed dining with Margaret, they did enjoy watching her sunbathe on deck.

If the cruise was a mini-vacation for Truman, he still kept a close eye on communist threats. While playing poker, he received a secret State Department message that Yugoslav communist General Josef Tito was threatening to invade the Italian town of Trieste. Truman ordered Captain Dennison to send a reply that “the SOB was going to have to shoot his way in.”

The president and his family left Missouri at Norfolk, and one crewman remembered: “He was a very down-to-earth person. . . . He didn’t stand on ceremony . . . he would sit there and talk to you about things that really mattered. . . . He worried about the little guy, the problems he was having. You really felt like he cared when he talked to you.”

During the next two years the Cold War became more bitter. Missouri remained on the East Coast, and each summer took academy midshipmen on training cruises to Europe and the Caribbean. During a visit to England in 1949, three enterprising midshipmen talked their way into Winston Churchill’s country house to pay him a visit. Churchill, a naval expert, spent several hours walking with them in his gardens talking about battleships. He then offered them drinks, cigars, and autographed copies of his books. Churchill’s astonished security guard told the delighted midshipmen: “I have seen some of the great people come and just get ushered out the door. He treated you like I’ve never seen anyone treated. The only reason I can think for his hospitality is that he likes Americans, he likes young people, and he likes the navy.”

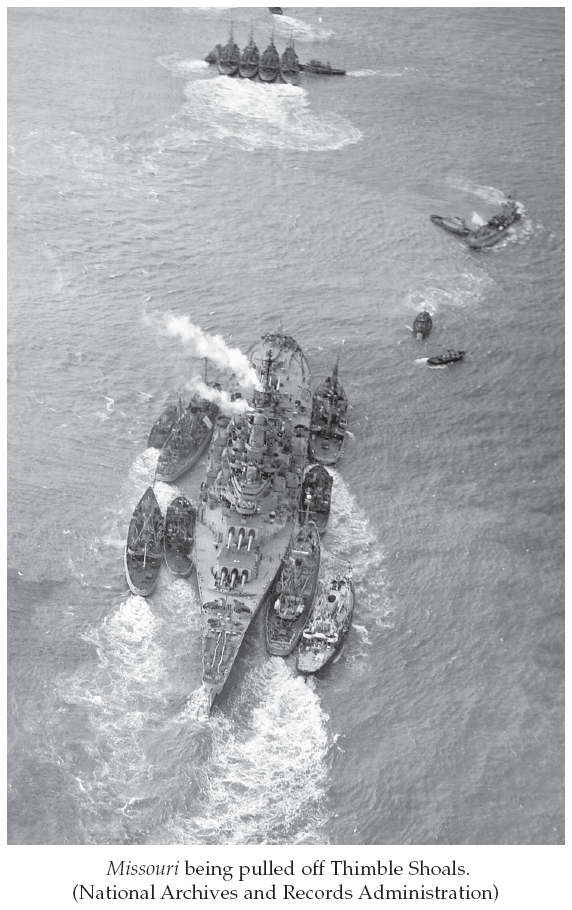

In September 1949 Captain William Brown, who had commanded a destroyer in World War II, took command of Missouri. Brown did not welcome advice from his officers, many of whom were young and inexperienced. The ship left Norfolk on January 17, 1950, and through a combination of faulty navigation, equipment failure, and Brown’s refusal to heed the warnings of his increasingly frantic senior crewmen and officers, Missouri ran almost half a mile up onto a shallow sandbar in full view of the admiral in his headquarters. The navy was terribly embarrassed that the president’s favorite ship had gotten stuck in one of their largest and oldest ports. The Russians and even other American military services ridiculed the navy, and newspapers and radio spread the story around the world.

The navy was determined to prove its professionalism by quickly freeing Missouri. Sailors labored to unload ammunition, fuel, and stores to lighten her. Divers used high-pressure hoses to blast the sandbar from around her, and a fleet of tugboats finally dragged her free on February 1. The ship’s band played the “Missouri Waltz” and “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” while the crew raised huge battle flags and signaled “Reporting for Duty.” Remarkably, the $100 million Missouri only suffered $50,000 damage, and repairs were completed in a week in drydock. After initially trying to blame his officers, Captain Brown took full responsibility at his court-martial and was convicted and disgraced. He later tried to commit suicide.

Congress tried to put Missouri in mothballs with her three Iowa-class sisters to pay for another aircraft carrier, but on June 25, 1950, the battleship was again called to war when 100,000 Russian-trained North Korean troops suddenly attacked South Korea. Missouri received urgent orders to take on hundreds of new crewmen and depart immediately for the Far East to support General MacArthur’s struggling United Nations forces.

Racing south at twenty-eight miles per hour, Missouri ran through a hurricane off North Carolina that swept away her helicopters, smashed her boats, and had her rolling in the high winds and seas. She dodged another storm off Hawaii and ran through a typhoon near Japan before finally reaching South Korea on September 15, 1950, one month after leaving the East Coast. Missouri immediately began bombarding North Korean targets with her huge sixteen-inch shells, and soon United Nations commanders noticed that whenever Missouri appeared, enemy troops moved away from the coast to avoid her terrible guns. While enemy troops could hear the approach of attacking aircraft, Missouri’s first massive shells always hit with absolutely no warning, leaving huge explosions, great craters, and shocked and deafened survivors.

Reporters and film crews recorded her actions, and in late October famous comedian Bob Hope visited the ship to entertain her crew. Missouri raced up and down the Korean coastline, screening American carriers and attacking enemy targets. In late October she shelled North Korean factories at Chongjin near China and Russia. In late November, however, the Chinese joined the war, and United Nations forces were again pushed back. In December Missouri covered the safe evacuation of the American Third Infantry Division and many thousands of South Koreans from Hungnam. Through the bitter Korean winter Missouri could strike in weather that kept aircraft grounded or on their carriers, and she was particularly effective at accurately hitting railroads, bridges, tunnels, and enemy supply and troop concentrations. Allied soldiers praised the great range, accuracy, and power of her guns, noting “the destruction and damage caused by 16-inch gunfire was particularly gratifying.”

At the end of March 1951 Missouri left Korea having fired almost three thousand sixteen-inch shells. As the first major warship to return from Korea, Missouri’s arrival in Long Beach, California, was broadcast on television. Missouri served again in Korea in the winter of 1952-1953 as the war was coming to an end, but tragedy struck when her captain, Warner R. Edsall, died of a heart attack on his bridge while bringing her into harbor in Japan in March 1953.

Dwight Eisenhower succeeded Harry Truman as president in January 1953, Joseph Stalin died in March, and the Korean War ended in July. Missouri and her sisters went back to routine training, including summer midshipman cruises, but it was now clear that they had been replaced by more advanced, powerful, and costly strategic weapons. President Eisenhower was forced to confront difficult budget choices, and battleships were an old-fashioned luxury when the United States had to build whole new types of weapons to face the Soviet threat. After thorough repair, preservation, and maintenance, Missouri was taken out of service and put into the Pacific Reserve Fleet in Puget Sound in February 1955. By 1958 her sisters Iowa, New Jersey, and Wisconsin had joined her, and for the first time in the twentieth century, the United States had no battleships on active duty. Even in reserve, however, Missouri continued to receive some 100,000 visitors each year who wanted to see the famous ship.

World War II had been a time of remarkable advances in military technology. The American navy perfected the use of fast task forces built around large aircraft carriers armed with scores of deadly bombers, torpedo planes, and fighters. The aircraft carrier became the new naval superweapon, and even the most modern battleships like Missouri were relegated to secondary roles using their radars and antiaircraft guns to defend the carriers from enemy air attack and their main batteries to support soldiers and marines fighting on shore. The carriers were now the most important, and the most expensive, warships, but the navy was faced with the huge expense of replacing now-obsolete wartime carriers with radically new ships specifically designed for modern jet aircraft. With their jet airplanes, small protective escort warships, and resupply ships, these supercarrier battle groups were able to project American power anywhere in the world, but at great cost.

The Soviets and United States were also developing the most terrifying weapon of the Cold War: nuclear tipped ballistic missiles. Once launched, these successors to the German V-2 could not be stopped by any defense and could reach their targets thousands of miles away within minutes. At first these ballistic missiles required large fixed launching bases and were vulnerable to counterattack by bombers or even enemy rockets, but in the mid-1950s the U.S. Navy began developing a ballistic missile that could be fired from a submerged submarine. By this time, the navy had harnessed nuclear power to drive ships. Once the U.S. Navy launched Nautilus in 1954 nuclear-powered submarines became, like aircraft carriers, jet airplanes, and ballistic missiles, major Cold War strategic weapons.

Missile-carrying submarines were especially attractive to American military leaders because of their invisibility. Even if a massive Soviet surprise attack crippled American strategic bombers and land-based ballistic missiles, the hidden submarines could retaliate and destroy the Soviet Union. These new superwarships were to be named for “distinguished Americans . . . known for their devotion to freedom,” and the first ballistic missile submarine, SSBN-598, was named George Washington. Early missiles were dishearteningly unreliable, and while George Washington first successfully fired a Polaris missile while underwater on July 20, 1960, the next four missiles failed. To the dismay of her crew, the rockets fell back and crashed against George Washington’s submerged hull.

Just a week before his assassination, on November 16, 1963, President John Kennedy watched a Polaris missile launch and wrote: “The Polaris firing I witnessed was a most satisfying and fascinating experience. It is still incredible to me that a missile can be successfully and accurately fired from beneath the sea. . . . The [effectiveness] of this weapon . . . as a deterrent is not debatable.”

This first generation was quickly succeeded by new fleet ballistic missile submarines, nicknamed “boomers,” designed from the start as strategic missile boats. Lafayette, SBN-616, the first of a class of thirty-one, was commissioned in 1963. Four hundred and twenty-five feet long and 33 feet in diameter, these boats weighed 7,250 tons, carried 16 Polaris missiles and a crew of 140 officers and men, and could “steam” at 34 miles per hour underwater and operate 900 feet below the surface. Their Westinghouse nuclear reactors generated some 15,000 horsepower, and each boat cost about $110 million. By this time, new Polaris A-3 missiles had a range of 2,500 miles with a payload of three 200-kiloton warheads. By comparison, the bombs that had destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki only had the power of 10 kilotons (10,000 tons) of dynamite.

The twelfth Lafayette boat, SSBN-629, Daniel Boone, was built at Mare Island Naval Shipyard in San Francisco Bay and was commissioned on April 23, 1964. During the next decades of the Cold War, Daniel Boone and her sister boomers continued their silent secret patrols, and because of their invisibility and invulnerability helped maintain the “balance of terror” that kept the superpowers at peace. Daniel Boone was the first boat armed with the new long-range, multiple-warhead Polaris A-3. The Lafayettes were designed for stealth and long life, and most outlasted the Cold War and the Soviet Union itself.

These submarines could go 400,000 miles between refuelings and were limited only by their crews’ endurance. The boats could even generate their own oxygen from seawater. Indeed, in 1959, Triton had circled the world underwater, traveling 36,014 miles in 84 days. Daniel Boone and her sisters were thus given two identical crews. While the “blue” crew was on shore training and resting, the “gold” crew was on their seventy-day underwater patrol. Normally, the boomers would submerge as soon as they left their bases at Guam, Rota, Spain, and Holy Loch, Scotland, and go quietly to patrol areas within range of their targets in the Soviet Union. They would then await the command to launch their forty-eight nuclear warheads against Soviet cities, factories, or military bases, all the while remaining silent to avoid detection by Soviet attack submarines. By 1972, American ballistic missile submarines had completed some one thousand such patrols.

Having served faithfully and silently during the most dangerous years of the Cold War, all the Lafayettes were decommissioned and scrapped as Russia and the United States began to relax their suspicion of each other. Daniel Boone was decommissioned in February 1994, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union on December 25, 1991. Her nuclear fuel removed and her radioactive reactor buried at Hanford, Washington, she and her sisters were cut to pieces in accordance with Russian-American agreements.

Because of their stealth and the great power of their nuclear missiles, ballistic missile submarines changed the way that navies looked at undersea warfare. The Russians had assembled a huge fleet of attack submarines to counter the mighty American surface fleet of aircraft carriers and to threaten Atlantic supply lines essential to supporting American and allied armies defending Western Europe. In 1948, just after the Soviets tried to starve the Western allies out of Berlin, the Soviet navy had 250 submarines. In 1960, as George Washington was beginning her first patrol, the Russian submarine fleet numbered 437 boats, and the Soviets, too, were beginning to build ballistic missile submarines to threaten American cities. Although the U.S. Navy remained the most powerful in the world, it needed nuclear attack submarines to defend carriers, guard American boomers, shadow the Soviet surface navy, collect intelligence, and neutralize the growing Soviet fleet of ballistic missile boats.

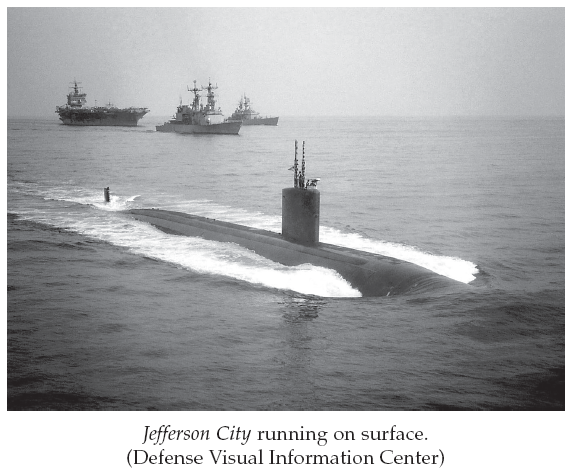

The first of sixty-two fast, powerful, quiet attack boats, SSN-688, Los Angeles, entered the fleet on November 13, 1976. These boats are 362 feet long and 33 feet in diameter, weigh some 6,000 tons, can reportedly dive as deep as 1,500 feet, and have 35,000-horsepower reactors that drive them faster than 30 miles an hour submerged. They carry crews of around 130 officers and men and are armed with torpedoes and Tomahawk cruise missiles that can be fired from their regular torpedo tubes. The Tomahawk, with a range of up to 1,400 miles at a speed of 550 miles per hour, can be used to attack either ships or land targets with nuclear or high explosive warheads.

During the remainder of the Cold War as many as six sister ships a year were completed at Newport News Shipyard or the Electric Boat Division of General Dynamics Corporation at Groton, Connecticut. While General Dynamics charged only $221 million each for the first boats, prices rapidly rose to $496 million per boat by 1981 and reached $900 million by the end of the Cold War.

The forty-eighth Los Angeles, Jefferson City, SSN-759, was begun on September 21, 1987, at Newport News. She was launched on August 17, 1990, just weeks after Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait and less than two months before a free Germany was reunited within NATO. She was finally commissioned on February 29, 1992, just two months after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the creation of the Russian republic. Her homeport is San Diego, California, and she is still patrolling with the Pacific Fleet. Since her commissioning, the American submarine fleet has been cut to fewer than twenty boomers and sixty attack submarines, but Jefferson City and her sisters remain alert.

The operations of American attack submarines are kept secret, but a number of stories have emerged about their dangerous Cold War missions and the silent undersea “war” between American and Soviet or Russian submariners. Because their mission is to “hide with pride” until ordered to launch their ballistic missiles against enemy targets, locating and shadowing boomers was the most critical mission for both American and Russian attack submarines. Sometimes, miscalculation or aggressive pursuit led to accidents. In December 1967 Daniel Boone’s sister George C. Marshall, SSBN-654, was hit by a submerged Soviet submarine in the Mediterranean, and in November 1974 another sister, James Madison, SSBN-627, hit a Soviet attack submarine while leaving the American ballistic submarine base at Holy Loch, Scotland. As late as February 1992, Jefferson City’s sister Baton Rouge, SSN-689, collided with a Russian submarine near the big Russian naval base at Murmansk in the Arctic above Norway.

Russian ballistic missile submarine patrol areas are in icebound northern “bastions” close to Russia. To operate in these frozen seas, later Los Angeles submarines like Jefferson City were built with reinforced sails for under-ice operations. To strengthen their offensive power, they were also equipped with twelve vertical launch tubes for Tomahawk cruise missiles, but these missiles were not fired against an enemy until after the Cold War had ended.

American submarines did not just stalk their Soviet targets; daring crews used their boats as “underwater U-2s” to collect intelligence on Soviet tactics, the performance of Soviet submarines and surface ships, and even on Soviet military plans. Specially equipped American submarines were able to tap into Russian undersea telephone cables and conduct other secret intelligence missions using specially trained crew members, divers, and even navy SEALs. The navy has also designed small submarines that ride in drydock shelters mounted piggyback on nuclear attack submarines until they reach their target areas.

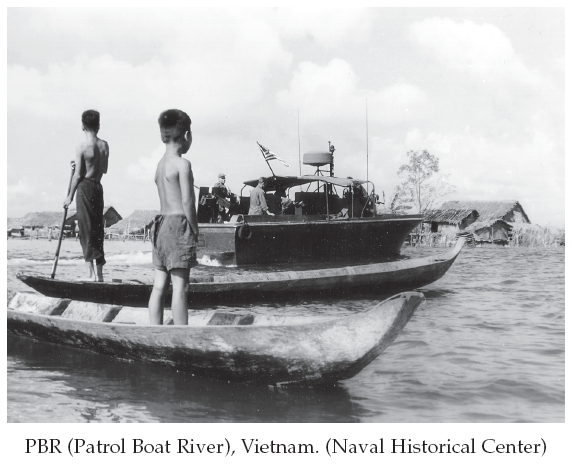

While war never broke out between the Americans and Soviets during the Cold War, the forty-five years between the end of World War II and the collapse of the Soviet Union was by no means a time of peace for the U.S. Navy. Many sailors died while collecting intelligence on the Soviet Union and her allies, and many more died in the hot wars of the late twentieth century. The longest and most bloody of these wars was fought in Southeast Asia. By 1964, U.S. Navy ships were patrolling the Vietnamese coast looking for northern weapons supply boats, and soon navy pilots were attacking North Vietnam from offshore aircraft carriers. Most of the fighting was in South Vietnam. The navy played a role there as well, manning a “brown water navy” of small patrol boats in the Mekong River delta. These little boats, with their small crews, operated in much the same conditions that faced David Dixon Porter’s Eads gunboats during the Vicksburg campaign of 1862–1863. Like Cairo and St. Louis on the Yazoo River, they were terribly vulnerable to ambush as they crept up muddy, narrow canals bordered by deep vegetation that could easily hide enemy soldiers. The sailors never knew whether local villagers were harboring guerrilla fighters, and like Porter’s sailors, they fought in terrible heat and humidity amid swarms of mosquitoes. As a sailor remembered: “You really feel like a sitting duck when you’re riding those boats . . . down the small canals. . . . The only trouble is [the Viet Cong] always gets the first punch.”

Still, despite some two thousand enemy ambushes and many casualties, many young sailors loved the freedom and excitement of the little riverboats. One crew of a thirty-foot fiberglass, jet-propelled Patrol Boat River (PBR) taunted a passing “tin can” destroyer by singing:

PBRs get all the pay,

Get the tin can out of the way.

PBRs roll through the muck,

While tin can sailors suck!

One of the earliest U.S. Navy river advisors was Lieutenant Harold Dale Meyerkord from St. Louis, Missouri, a graduate of the University of Missouri. Fighting beside his Vietnamese allies in more than thirty firefights, he was wounded twice. Famed war correspondent Dickey Chapelle profiled him in a National Geographic magazine article on the “Water War in Vietnam.” After Meyerkord died, on March 16, 1965, in a Viet Cong ambush while leading his boats, Chapelle described him as “audacious, ebullient . . . husband, father, leader and teacher of men . . . dead . . . on a muddy canal 9,000 miles from Missouri.” On November 9, 1965, Secretary of the Navy Paul Nitze personally gave the navy’s highest award for heroism, the Navy Cross, to his widow, Jane Schmidt Meyerkord, and his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Harold E. Meyerkord. Chapelle herself had been killed in Vietnam just five days earlier.

The navy moved quickly to honor Meyerkord. Less than a year later the keel was laid at San Pedro, California, for a new Knox-class frigate, DE-1058, Meyerkord. Launched on July 15, 1967, as the fifth in a class of forty-six antisubmarine ships, she was commissioned on November 28, 1969, and cost about $18 million. She was 438 feet long, weighed 3,000 tons, carried a crew of 220 officers and men, and was designed to fight Soviet submarines. Unfortunately, she and her sisters had a top speed of only 33 miles an hour and were thus slower than either American aircraft carriers or the newest Soviet November nuclear submarines. Still, she was the first ship named for a serviceman killed in Vietnam to return to fight in the same war. Beginning in March 1971 she served three times in Vietnamese waters, providing naval gunfire support with her single 5-inch gun. She also escorted American carriers in the western Pacific, protecting them from North Vietnamese airplanes or gunboats. Meyerkord also served as lifeguard if carrier planes crashed on landing or takeoff or sailors fell overboard.

Her last Vietnam tour began in January 1975 as the Republic of Vietnam was collapsing. After rescuing thirty-one crew members from a sinking freighter at the end of January, she joined “Operation Eagle Pull” evacuating Westerners from Phnom Penh, Cambodia. In April, she helped rescue Americans and Vietnamese in “Operation Frequent Wind” as Saigon fell to the victorious North Vietnamese. A month later, she was part of the carrier group supporting American military efforts to rescue the American crew of the freighter Mayaguez captured by Cambodian communists.

No longer required to support a war in southeast Asia, Meyerkord remained on duty in the Pacific. Now, however, aside from her responsibility to escort carriers, Meyerkord also rescued fishing boats and pleasure yachts in the stormy Pacific. Her crew underwent nuclear weapons training and inspection so Meyerkord could be equipped with nuclear antisubmarine warheads. They took this responsibility so seriously that in February 1981 the ship earned an outstanding overall nuclear weapons certification. Through the remainder of the Cold War, Meyerkord continued to operate in the Pacific from her San Diego base, frequently cruising to the western Pacific and escorting American carrier groups. In 1983 she was one of the ships sent to recover wreckage from the Korean Airlines 747 jumbo jet KAL-007 shot down by Soviet fighters for straying into Soviet territory. Meyerkord’s crew won a Meritorious Unit Citation for this grim duty.

Even without the war in Vietnam, the United States faced many challenges in the 1970s and 1980s. The Soviets continued to encourage communists to seize power in countries in southeast Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and South and Central America. Wars between Israel and her Muslim neighbors inspired Islamic radicalism and terrorism, and in the 1970s Middle East oil producers began using oil prices as a weapon against the West. In Iran, radicals overthrew the pro-Western Shah, occupied the American embassy in Tehran, and took American diplomats hostage. At the end of 1979 the Soviets sent troops into Afghanistan and began their decade-long war against Muslim fighters. Finally, in September 1980, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein attacked Iran, beginning a war that went on for a decade and threatened Western oil shipments through the Persian Gulf. The United States was thus faced with growing Muslim radicalism and Middle East unrest while the Soviet Union appeared to be an increasingly aggressive military and ideological global threat.

The war in Vietnam and inflation had strained the navy’s budget, and there had been repeated efforts to scrap the four mothballed Iowa sisters. President Ronald Reagan felt that their awesome power and reputation would be valuable additions to the fleet. Despite strong objections to the cost of updating and manning these old warships, and concern about their vulnerability to new weapons like nuclear cruise missiles, he ordered them back into service.

In May 1984 Missouri was towed to Long Beach for her $468-million reactivation. To supplement her original 16-inch guns, she was equipped with 8 Tomahawk launchers as well as 4 Phalanx anticruise missile guns. She also received new radars, air-conditioning, and a modern “combat engagement center” from which her captain could command during combat. Missouri’s modernization was particularly delicate because of the need to protect the historic World War II surrender plaque and a large mural in the admiral’s quarters used by Harry Truman on his return from Rio in 1947. The admiral’s quarters were converted into the new electronic combat control center, but the mural remained. Many 5-inch and other obsolete antiaircraft guns were removed to allow space for Tomahawk launchers, but the navy was still forced to salvage many old parts from museum battleships like North Carolina to return Missouri’s machinery to operation.

The first of Missouri’s new crew arrived in September 1985. Her new senior sailor, Master Chief John Davidson, had served aboard Missouri forty years earlier during her Istanbul and Rio cruises in 1946 and 1947. He was so anxious to rejoin the ship rather than retire that “I told them I’d pay them to let me serve.” Missouri was recommissioned in San Francisco on May 10, 1986. Captain Lee Kaiss chose sailors from Missouri to stand the first watch, and Margaret Truman Daniel was again the ship’s sponsor. At the commissioning, Captain Kaiss said: “On October 27, 1945, when President Harry S. Truman stepped aboard . . . he said ‘this is the happiest day of my life.’. . . I know exactly how he felt.” At a dinner and fireworks display for the crew sponsored by the state of Missouri, Margaret addressed them: “Captain Kaiss and the men of Missouri . . . please take good care of my baby.” As a sailor remembered, “the crew went nuts” and gave her a standing ovation. The only sour note of the celebration was that Governor John Ashcroft had resisted returning the ship’s silver service until, according to Captain Kaiss, the navy was prepared to send federal marshals to Jefferson City to reclaim it.

In September, Missouri set off on an around-the-world goodwill cruise. After laying a wreath at Pearl Harbor’s Arizona memorial, Missouri retraced the Great White Fleet’s route and again saluted the famous leper colony on Molokai. Missouri then visited Sydney, Australia, where her crew received as warm a welcome as had greeted the Great White Fleet in 1908. Hundreds of thousands of people mobbed the ship, and the crewmen were treated so well that sailors from other ships began sewing Missouri patches on their uniforms to get free drinks from the hospitable Australians. A cousin of British admiral Lord Fraser, who had represented Great Britain at the Japanese surrender in 1945, spoke for the gratitude of many Australians for America’s role in World War II when she visited the surrender plaque and said: “I feel I should get down on my knees and kiss the deck.”

In early November Missouri passed through the Suez Canal and again visited Istanbul, where forty years earlier she had encouraged the Turkish and Greek governments to resist communist aggression. After crossing the Atlantic she squeezed through the Panama Canal one last time, losing some paint in the process. As her captain recalled: “It sounded—magnified by ten thousand times—like fingers going down a blackboard. It was awful, the loudest screeching you ever heard in your life.”

Missouri returned to Long Beach on December 19, 1986. The cruise was the first around-the-world voyage by an American battleship since that made by the Great White Fleet, and it would be the last. Missouri had entertained huge crowds at every port, showing the American flag and reminding the world of America’s great naval power.

During her cruise, Missouri had stayed clear of crisis points then occupying the attention of the U.S. military. In the Persian Gulf, the bitter war between Iran and Iraq was threatening Western tankers carrying oil to Europe and Japan, as both sides fired on ships leaving the other’s ports.

In January 1987 Kuwait asked the United States to allow Kuwaiti tankers to fly the American flag so the U.S. Navy could protect them from Iranian mines, armed speedboats, and Chinese-made Silkworm cruise missiles. The U.S. Navy quickly increased its presence in the Persian Gulf. On May 17, the American frigate Stark was badly damaged by two French-built Exocet cruise missiles mistakenly fired by an Iraqi fighter plane. Although thirty-seven sailors were killed, the crew managed to save the ship. It was clear that modern cruise missiles were a deadly threat to both tankers and thin-skinned frigates and aircraft carriers. The navy thus ordered the heavily armored Missouri into the tanker war. As one of Missouri’s officers said: “we knew we were sending a very powerful signal by sending the battleship up there, and it wasn’t lost on anybody.”

In early October 1987, Missouri led a convoy of tankers and escort frigates through the narrow Strait of Hormuz into the Persian Gulf. As they passed Iranian Silkworm batteries, Missouri’s sensors warned that missile-targeting radars were tracking them. With her own main sixteen-inch guns aimed at the batteries, Missouri’s captain James Carney ordered her crew inside her armor while he remained on the bridge during the night-long transit. The Iranian guns remained quiet, and the ships passed safely. Missouri remained near the strait while the tankers sailed on to Kuwait escorted by smaller warships. As they neared Kuwait the next day, the tanker Sea Isle City was hit by a Silkworm.

Missouri escorted six more convoys through the dangerous strait past the Iranian missile sites, but her crew grew frustrated by the lack of action, the burning Arabian heat, and the lack of mail from home. Twice during Missouri’s hundred days on station, her captain allowed “steel-beach” parties on the helicopter landing pad at which each sailor was allowed two beers. The battleship finally left the war zone on November 24 and arrived at the island naval base of Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean to discover that an officer had written the newspaper advice columnist “Dear Abby” complaining that his sailors were receiving so little mail. In response to Abby’s appeal, tens of thousands of people wrote, and Missouri’s men were buried in mail. Missouri reached Sydney, Australia, and received another hearty welcome. So many Australians offered hospitality that many sailors and marines spent Christmas Eve with one family and Christmas Day with another.

In April 1989 the men of the four American battleships were shocked by the explosion of one of Iowa’s sixteen-inch guns, which killed many in the turret. After careful investigation and testing of the navy’s forty-year-old gunpowder, Missouri was again allowed to fire her main battery in September. Her captain, John Chernesky, personally fired the first shot from inside her turret. Thereafter, he insisted on frequent gun drill to rebuild turret crew confidence.

In July 1989, while Chernesky was ashore, the navy allowed the singer Cher to film the music video for “If I Could Turn Back Time” aboard Missouri. To the crew’s delight she wore such a skimpy costume that columnist Jack Anderson complained: “if battleships could blush, Missouri would be bright red.” Chernesky refused to blame his officers for the scandal, and whenever Missouri refueled at sea he played the song over the loudspeakers. A tough but popular officer, Chernesky was replaced in June 1990 by Captain Lee Kaiss, who had recommissioned Missouri in 1986. In July, with the Cold War ending, the navy again decided to deactivate New Jersey and Iowa, and it warned Kaiss that Missouri was next.