CHAPTER SIX

A New World, New Threats, and New Ships

The Iran-Iraq war had ended with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq the strongest military power in the region, but saddled with a huge $37 billion war debt. Because of American concern about Iran’s militant hostility, Presidents Reagan and Bush had supported Iraq, providing aid and intelligence to help fight Iran. The United States even forgave the deadly attack on Stark as a case of mistaken identity. Now, Saddam began demanding financial aid from other oil-rich Arab countries and belittling American power and determination.

On August 2, 1990, Iraqi Republican Guard divisions overwhelmed the small Kuwaiti military and within two days captured the whole country. Missouri was quickly ordered to the region. Her crew received chemical warfare training, and the ship was equipped with unmanned Pioneer drones equipped with TV cameras to serve as spotters for her gunfire. Because both Iran and Iraq had scattered thousands of mines throughout the Persian Gulf, mine disposal experts also joined the crew. With her sixteen hundred-man crew still being trained, Missouri left Long Beach on November 13. Because of her fame, and because the navy had already announced her retirement, CNN broadcast her departure live. On January 3, 1991, she passed through the Strait of Hormuz into the Persian Gulf. Six days later, Missouri’s antimine team destroyed their first Iraqi mine. As a Vietnam veteran in her crew remembered: “That mine woke up the entire crew. Those of us who remembered, and [the young sailors] who didn’t.”

As the allied coalition assembled a great army to eject the Iraqis from Kuwait, the navy’s experience during World War II and the Cold War proved very valuable. The navy had learned how to conduct a tight blockade during the Vietnam War when the fleet patrolled twelve hundred miles of Indochina coastline in Operation Market Time. Hundreds of Iraqi and other ships were inspected, with no casualties despite occasional Iraqi resistance. World War II and Vietnam had also taught the navy how to supply a combat fleet far from home.

Among the fleet of supply ships supporting coalition warships was the fleet oiler Kansas City, AOR-3, a member of the seven-ship Wichita class built by General Dynamics in Quincy, Massachusetts, during the Vietnam War. She had been commissioned in 1970 as a “multi-purpose replenishment ship” to carry fuel, ammunition, food, and other supplies to the fleet at sea. Able to carry over twenty thousand tons of supplies, and with a top speed of almost twenty-three miles per hour, she could keep pace with battleships and carriers. She also carried helicopters to supply warships from the air. Kansas City kept Missouri and other coalition warships “topped off” with ammunition and fuel and served until 1994 when she was finally decommissioned.

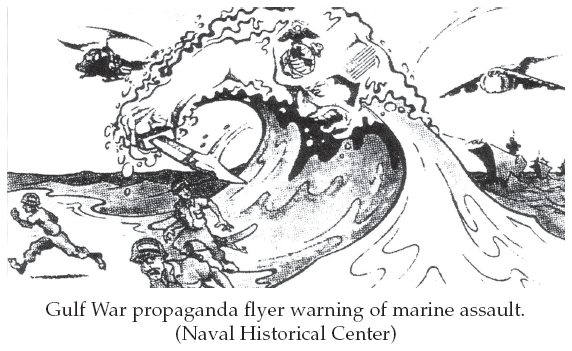

As the armies and navies assembled to drive the Iraqi invaders from Kuwait, General Norman Schwarzkopf and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs General Colin Powell planned a great deception to trick Saddam into concentrating his attention and armies on Kuwait itself. Iraqi forces were constructing a strong defensive “Saddam Line” of fortifications south of Kuwait City and fortifying the coastline with bunkers as the Germans had done in Normandy in 1944. Schwarzkopf put two marine divisions on the Saudi-Kuwait border and assembled marine amphibious forces supported by Missouri and Wisconsin offshore. The United States dropped thousands of propaganda leaflets on Iraqi positions showing a cartoon of a terrifying marine tidal wave backed by aircraft carriers as Iraqi soldiers fled for their lives.

In the early hours of January 17, 1991, President Bush ordered massive air attacks on Iraq. The navy launched waves of carrier aircraft and Tomahawk cruise missiles as part of the biggest air attack since World War II. Missouri fired 6 Tomahawks at Baghdad, and an Australian naval officer watching the nighttime attacks called them “altogether a most incredible and unforgettable sight.” In the first day, the navy launched 122 Tomahawks. Missouri’s crew could listen to live CNN broadcasts from Baghdad as the Tomahawks hit their targets.

At the end of January, as air attacks continued, Iraqi troops from Kuwait captured the deserted Saudi border town of Khafji. The Saudis were deeply offended by this Iraqi insult, and Saudi and Qatari tanks supported by marine helicopters soon recaptured the town. Missouri, guided by Saudi pilots, crept through water so shallow that she only had three feet of clearance under her keel to get within range of Iraqi positions. Using her drone to find targets, she fired almost two hundred rounds from her sixteen-inch guns. The crew was able to watch the shells hit with the drone’s TV cameras, and the video was broadcast to every television set on the battleship. The Iraqis tried to hide their positions, but the drone watched an Iraqi truck drive from bunker to bunker delivering supplies. Missouri’s crew plotted the route, and then hit the concealed bunkers with sixteen-inch shells.

The shallow Kuwaiti coastal waters made it impossible for modern navy ships to get close enough to use their five-inch guns, and the fleet was fortunate that President Reagan had insisted on recalling the battleships to active duty. With their heavy armor they were relatively safe from mines and cruise missiles, and their sixteen-inch guns could deliver devastating long-range blows to coastal defenses. In early February, Wisconsin and Missouri moved close to the Kuwaiti border and shelled radars, artillery, and troop bunkers. Apparently angry that the navy was getting such good publicity with its Tomahawks and battleships, General Schwarzkopf ordered his navy commander Vice Admiral Stanley Arthur to “stop firing the goddam [sixteen-inch guns of the] battleships” or any more Tomahawks.

Still, the battleships had a vital role in Schwarzkopf’s attack plans. Once the ground war began, the Iraqis had to believe that the marines would storm ashore to recapture Kuwait. As Arthur said: “I knew that the Iraqis always expected to see a battleship with amphibious landings. All I had to do was start moving the battleships and then line [our] fine marines . . . up behind them, and there was no doubt in anybody’s mind that we were coming.”

On the morning of February 23, 1991, Wisconsin began shelling Iraqi defenses as Arab troops and two marine divisions began advancing into Kuwait. Late that night, from a small coastal area that had been swept of mines, Missouri began shelling Iraqi troops on Faylaka Island outside Kuwait’s harbor. Steaming back and forth inside the mineswept safe zone, Missouri sometimes had to aim her forward turrets back “over her shoulder” to keep Iraqi positions under fire.

The next day the main coalition ground assault began. As the heavy army divisions stormed through the Iraqi desert destroying Iraqi tanks and racing to surround and cut off Saddam’s occupying army, the battleships and marine ground divisions continued to attack Iraqi forces in Kuwait. Marines cut their way through Saddam Line minefields and moved toward Kuwait’s airport “like a snake getting ready to strike.” In the early hours of February 25, Missouri began shelling Kuwait’s Ash Shuaybah seaport. To paralyze the Iraqi reserves waiting for a marine amphibious assault, Missouri pretended to be both battleships. She first fired one sixteen-inch shell every forty-five seconds, but after two hours built up to a shell every five seconds as if the ships were softening up the beach so the marines could storm ashore.

During the bombardment, Iraqi batteries fired two Silkworms at Missouri. One crashed harmlessly into the sea, but the crew saw a huge fireball as the second raced toward the battleship at over six hundred miles per hour. Her bridge crew scrambled for cover, but British destroyer Gloucester shot down the Silkworm as it passed behind Missouri. The Silkworm explosion was so bright that Missouri’s lookouts at first thought that Gloucester herself had exploded. Missouri’s Phalanx antimissile guns had locked onto the Silkworm, but the Phalanx computer had decided that the passing missile was no threat and thus had not fired. During World War II hundreds of crewmen had manned dozens of antiaircraft guns throwing storms of lead at oncoming threats. Now, four computer-guided unmanned guns and her small escort ships were Missouri’s only antiaircraft protection. Her drone quickly spotted the hidden Silkworm battery, which Missouri destroyed with thirty sixteen-inch shells. During a later false alarm, Missouri suffered her only Gulf War casualty when a sailor was slightly wounded by Phalanx fire from an escort frigate.

As the First Marine Division approached Kuwait’s airport, Wisconsin shelled Iraqi tank concentrations on the airfield. Her drone recorded the destruction and showed Iraqi soldiers abandoning their vehicles to escape the gunfire. On February 27, marines liberated the empty American embassy. The next day, exactly one hundred hours after the ground war began, President George H. W. Bush ordered a ceasefire. On March 1, Wisconsin sent her drone over Faylaka Island where an Iraqi marine brigade was still dug in. Recognizing the drone, and knowing that sixteen-inch battleship shells would soon follow, Iraqi soldiers tried to surrender to the tiny unmanned, unarmed aircraft. U.S. Marines landed and captured fourteen hundred soldiers and over one hundred officers. Generals Powell and Schwarzkopf considered holding ceasefire talks on Missouri so that Saddam and the whole world would understand the extent of his defeat. They finally decided to meet Iraqi delegates in the middle of the desert to demonstrate that an international coalition rather than exclusively American power had won the war.

Missouri and Wisconsin left the Gulf in March, with Wisconsin immediately entering the reserve. Stopping at Pearl Harbor on her way home, Missouri welcomed sailors’ family members for the final leg back to Long Beach. On May 9, in an impressive demonstration for the families, Missouri fired her huge sixteen-inch guns for the last time. The battleship returned to Long Beach to the warm welcome of waiting families. In the all-volunteer navy, more than half the crew were married, and during the six-month war deployment some fifty babies had been born. Captain Kaiss’s wife, Veronica, arranged for the new mothers and their babies to be the first aboard to greet their returning husbands.

That summer and fall Missouri, again the only active battleship, made a final West Coast farewell cruise to Seattle, Vancouver, British Columbia, and San Francisco. Governor John Ashcroft and his son Andrew were aboard for the final leg from San Francisco back to Long Beach in October. While at Long Beach, Missouri was visited by actor Steven Seagal, then planning the movie Under Siege about terrorists capturing the battleship. Because the movie involved an officer betraying the ship to terrorists, neither the navy nor Missouri’s officers were enthusiastic about helping the moviemakers. Action scenes were thus filmed on museum ship Alabama in Mobile Bay. Still, the film crew shot beautiful aerial film of Missouri leaving Long Beach in November on her way to Hawaii for the fiftieth anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack, as well as film of the ceremonies at Pearl.

Everybody understood that the journey to Hawaii was Missouri’s last cruise, and during the voyage a reporter from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote an article on the ship and crew. As crewman John Lewis of Palmyra, Missouri, told him: “I’m losing a member of my family. Its really hard to accept and understand. . . . There are only two kinds of sailors in the navy. Those who have been on a battleship and those who wish they could.”

On the morning of December 7, 1991, twelve hundred guests arrived, including President George Bush, who along with his wife, Barbara, briefly toured the ship. General Colin Powell and his wife also came aboard and were eagerly greeted by crew members, Arizona survivors, and other guests.

Upon her return to California, Missouri unloaded all her ammunition for the last time. Captain Kaiss had insisted that the battleship be fully armed on her Hawaii voyage. As the battleship entered Long Beach harbor for the last time, she was honored by whistle salutes from every ship in the port. Missouri was decommissioned for the last time on March 31, 1992, by Captain Lee Kaiss, who had presided at her recommissioning six years earlier. Among the guests at this sad ceremony was Missouri congressman Ike Skelton, whose father had served on the earlier Missouri. At the end of the ceremony her remaining six hundred crewmen filed off the ship, with Captain Kaiss being the last to depart. He was the last captain of the last American battleship.

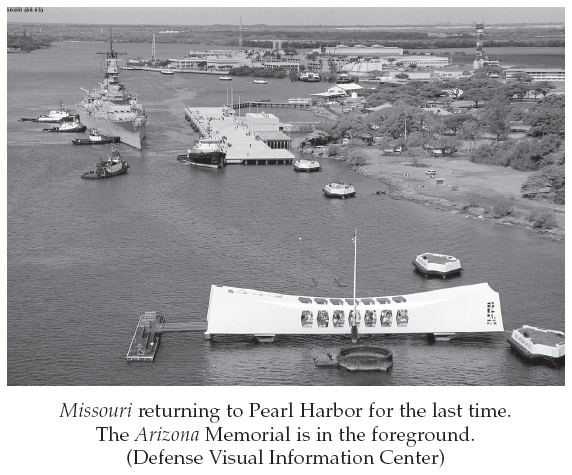

Missouri was towed to the reserve fleet in Bremerton, Washington, where three years later she again briefly played the central role in ceremonies marking the fiftieth anniversary of the Japanese surrender. The navy had finally decided that the United States could no longer afford these great warships. By the Gulf War, the annual payroll alone of her all-volunteer crew was more than three times her total annual budget at the beginning of the Cold War in the late 1940s. In 1996, she was turned over to a private Missouri memorial foundation, and on June 22, 1998, she returned to Pearl Harbor for the last time. She is now permanently moored at Ford Island near the Arizona Memorial.

The Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan and Eastern Europe, the decisive victory in the Gulf War, and the final collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of 1991 encouraged many to believe that the world was entering a new era of world peace and prosperity enforced by the American superpower. The U.S. Navy had a monopoly on great strategic warships able to demonstrate invincible American military force. The navy had perfected carrier warfare in the Pacific, building a fleet of Essex-class fleet carriers whose airplanes destroyed the Japanese navy. Although rendered obsolete by jet aircraft, many served not only in Korea but also in Vietnam.

The first real postwar generation of carriers, the four Forrestal-class ships, were twice as heavy and almost one hundred feet longer than the Essex class. Commissioned between 1955 and 1959, they served through the Cold War and Gulf War. One, Ranger, fought with Missouri and Wisconsin in the Persian Gulf. The last, Independence, was only decommissioned in September 1998 after Harry S. Truman joined the fleet. By the late 1950s it was clear that thanks to the strong-willed Admiral Hyman Rickover, nuclear energy would power the American submarine fleet. The value of nuclear power for surface ships was less clear however. The first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, Enterprise, was the largest and most expensive warship ever built when she was commissioned in 1961. She was so expensive, at $440 million, that Congress was reluctant to approve more nuclear carriers.

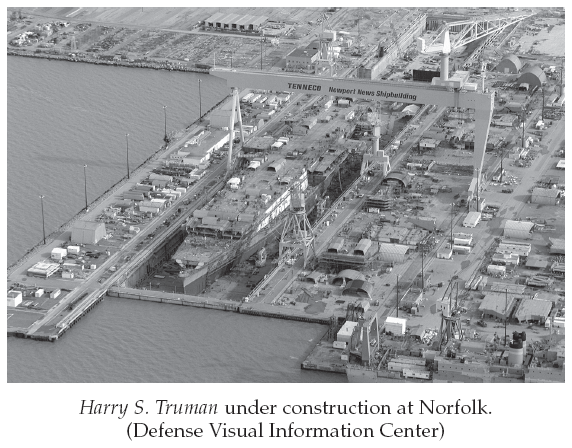

Only in 1967 did Congress finally authorize another nuclear aircraft carrier: Nimitz, CVN-68. This basic design proved so successful that in 1989 work began on the eighth Nimitz, Harry S. Truman, at Newport News Shipyard. These are the largest and most expensive warships ever built, costing over $4.5 billion each. They weigh over 70,000 tons, or over 100,000 tons fully loaded with crew, aircraft, aviation fuel, ammunition, and supplies. Their two Westinghouse reactors drive four General Electric steam turbines producing a total of 280,000 horsepower that propel them over 35 miles per hour. Their flight decks measure 1,096 feet by 251 feet, or over 4 acres, and carry 4 steam catapults to launch the 80 aircraft in their air wings. These are the first American warships to carry women as permanent crew members.

Because of their great size, Harry S. Truman and her sisters are built of 190 modules, some weighing as much as 900 tons. These giant building blocks are assembled in drydock using huge movable cranes. In all, 60,000 tons of steel and 900 miles of cable and wiring are used in construction. Once the hull is complete, the dock is flooded and the ship moved to a pier for completion. Harry S. Truman’s newest sister, Ronald Reagan, was completed in 2003. Harry S. Truman was christened on September 7, 1996. Sponsor Margaret Truman Daniel could not participate, but both Virginia senators and Missouri congressman Ike Skelton watched as a bottle of Missouri champagne was used to christen her. Two years later, on July 25, 1998, just one month after Missouri returned to Pearl Harbor for the last time, President Bill Clinton and Secretary of Defense William Cohen, along with Ike Skelton and Missouri governor Mel Carnahan, attended the commissioning. President Clinton said that the new nuclear carrier was an enduring way to remember the country’s thirty-third president. Captain Thomas G. Otterbein responded: “The qualities of hard work, honesty, integrity, and moral courage which made Harry S Truman an enduring figure in our nation’s history, also permeate this crew. I’m proud to be their captain.”

The crew was equally proud of their ship. They designed an emblem combining eagles to symbolize Harry Truman’s well-known integrity and honesty, the name Truman in the shape of the ship’s hull, and his famous motto: “the buck stops here.” The seal is embedded in the deck in many passageways, and a large seal is embedded on the bridge between the captain’s chair and the ship’s surprisingly small wooden wheel. The ship’s battle flag also carries on the Truman tradition, being similar to the flag carried by Captain Harry Truman’s World War I Battery D of the 129th Field Artillery Regiment. Crossed artillery cannons are superimposed over carrier Harry S. Truman’s number, CVN-75, to symbolize the relationship between World War I firepower and the carrier’s great power. As her executive officer, Captain Ted Carter, noted in October 2002, the ship carries by herself the seventh largest air force in the world. Finally, the flag carries the ship’s battle cry: “Give ‘em Hell.” As crew members and visitors come aboard, they pass a small museum with one of Truman’s World War I uniforms, his famous walking cane and fedora hat, and pictures and quotations from his life.

Longer than the Empire State Building, Harry S. Truman is literally a small floating city with some three thousand crew members and another two thousand men and women in her air wing. The ship has its own newspaper, television station, store, and hospital, as well as machine shops to keep herself and her aircraft operating. The crew keep track of news via satellite, and can communicate with their families via e-mail and videophone. Her kitchens serve over eighteen thousand meals a day, and one crewman told the New York Times that Captain Otterbein worked so hard to keep the crew happy that “this is a little slice of paradise.” Several hundred women serve aboard, and although the ship is an enormously complicated and extremely hazardous floating airfield and high-tech war machine, over a thousand of her crew are high school graduates younger than twenty-one years old.

Harry S. Truman carries three fighter and fighter-attack squadrons as well as electronic warfare, early warning, and antisubmarine aircraft. No other nation on earth has ships like Harry S. Truman and her Nimitz sisters. Both during the Cold War and since, American aircraft carriers have been stationed around the world in critical areas, especially the Mediterranean, western Pacific, and Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf. Each ship remains on station for six months and then is replaced by another carrier while it returns to its home port for overhaul and training. The Nimitz sisters are designed for fifty years of active service and only require refueling every twenty-five years or every million miles of steaming. They carry more than three million gallons of jet fuel for their aircraft but can be resupplied at sea during their six-month tours.

Harry S. Truman has 2 squadrons of McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 fighter-bombers, the “Bulls” and the “Gunslingers.” These planes, built in St. Louis, Missouri, weigh 66,000 pounds, have a top speed of 1,180 miles per hour, and can carry deadly smart bombs able to hit small targets with pinpoint accuracy.

Powerful as she is, Harry S. Truman is only the centerpiece of a huge battle group, which also includes a cruiser, five destroyers, a frigate, a nuclear attack submarine, and two supply ships. With fifteen thousand sailors, the battle group protects and resupplies Harry S. Truman while she remains ready at any time day or night to send her aircraft against America’s enemies.

From her Norfolk base, Harry S. Truman’s crew and pilots spent 1999 and 2000 training and preparing for their first six-month operational cruise. Because the navy was finding it difficult to recruit enough sailors for its worldwide commitments, Harry S. Truman went to sea lacking several hundred crew members. Her crew thus had to work longer shifts, often twelve hours at a time, and many sailors had to take on additional duties to keep the ship operating. Just before her first full deployment, her sailors received a painful reminder from another Missouri ship of the new threats facing America and the navy.

During the Cold War, the greatest threat to American national interests and the U.S. Navy came from the Soviet Union and other rival states. As the Soviet threat disappeared, Americans found themselves under increasing attack all over the world from shadowy terrorist groups. While no country can challenge the American fleet, small groups of suicidal terrorists could strike as the navy is called upon to carry out American foreign policy in the world’s most dangerous regions.

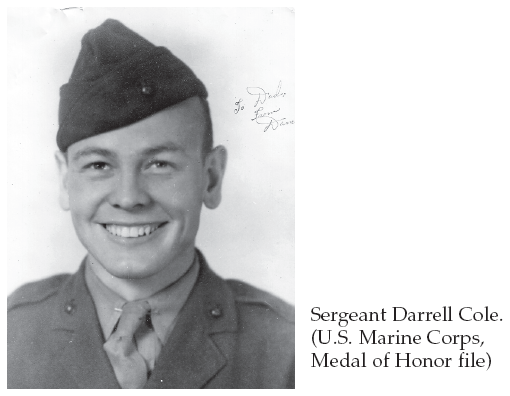

Cole is one of the first 28 original Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyers designed to defend aircraft carriers against attack by aircraft or missiles. These ships are equipped with Aegis antiaircraft defense systems so sophisticated that they can even be used in the new national missile defense against ballistic missile attack. Weighing 6,000 tons, and powered by four General Electric turbines with a total of 100,000 horsepower, Cole carries a crew of 22 officers and 315 sailors. She is very heavily armed, with 90 Tomahawks, antisubmarine torpedoes, one 5-inch gun, and two Phalanx antimissile guns. She cost almost $1 billion and was built by Litton/Ingalls Shipyard in Pascagoula, Mississippi. At 505 feet, the Arleigh Burkes are almost as big as the World War II cruiser St. Louis, and unlike many modern lightweight warships, they are built of high-strength steel with extra Kevlar armor. Cole, the seventeenth Arleigh Burke, was launched in February 1995 and commissioned in June of 1996. She was named for marine sergeant Darrell Samuel Cole, born on July 20, 1920, in Flat River, Missouri. He enlisted in the marines on August 25, 1941, “for the duration of the national emergency” and was assigned as a battlefield messenger. He was sent to Guadalcanal during the bitter jungle fighting and proved himself as a machine gunner. He fought in some of the bloodiest island campaigns of the Pacific war, was wounded, and earned the Purple Heart and Bronze Star for his “resolute leadership, indomitable fighting spirit, and tenacious determination in the face of terrific opposition.” On February 19, 1945, Sergeant Cole led his machine gun team ashore during the first assault on Iwo Jima. Under heavy fire, he personally destroyed several Japanese bunkers with hand grenades before being killed by an enemy grenade. He received the Medal of Honor for his: “dauntless initiative, unfaltering courage, indomitable determination. . . . Sergeant Cole served as an inspiration to his comrades, and his stouthearted leadership in the face of almost certain death sustained and enhanced the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.”

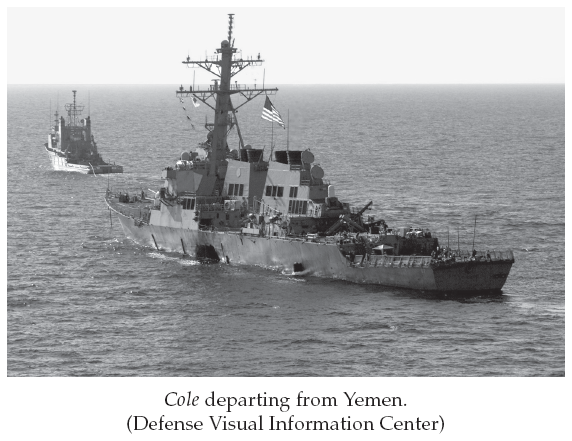

Cole left her homeport, Norfolk, August 8, 2000, on her way to the Persian Gulf. Among her crew was Chief Gunner’s Mate Norm Larson, who had been with Cole since her commissioning four years earlier and was in charge of her powerful missile battery. His mother lives in Columbia, Missouri, and his sister on a nearby farm. In October, Cole stopped for fuel at the port of Aden in Yemen. Her captain, Commander Kirk S. Lippold, had been an aide to the secretary of the navy and was known as an outstanding officer, a careful, precise “water walker” destined for great success. Still, he considered Aden to be so safe that his guards carried unloaded weapons as they watched small boats unloading garbage and bringing food and supplies to the ship. Just before noon on October 12, 2000, as many of Cole’s crew were lined up in her mess hall, two Arabs in another small motorboat approached the ship and waved at the watching guards. They waved back as the two men stood at attention and detonated several hundred pounds of high explosives. The blast tore a hole forty square feet in the ship just at the mess hall and engine room, killing seventeen crew members and wounding forty-two others. As a female sailor wrote to her family:

The ship list[ed] to the port side. I have never seen such a horrible sight. Everything was blown toward the starboard side and mangled. There were people pinned against the walls, body parts in and under metal . . . very few people cried. How we avoided [a fire] is a mystery to everyone.

As a thousand tons of water poured into Cole, her crew rallied to stop the flooding, restore light and power, and help the wounded. Chief Larson, who was only seventy-five feet from the explosion, was thrown violently against the door of his office. Although he first thought Cole had been rammed by another ship or had suffered an accidental fuel explosion, he ordered other sailors to their battle stations and got a rifle from the armory. Larson then escorted Captain Lippold to the bridge and organized security guards to protect the crippled ship.

With no toilets or showers the crew worked around the clock for five days in terrible heat until the last bodies were recovered from the flooded engine room. Within a day, FBI investigators arrived, and within a month U.S. and Yemeni authorities blamed the attack on Usama bin Laden’s al Qaeda organization, which two years earlier had killed 224 and wounded 6,000 with bombs at the American embassies in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Nairobi, Kenya. Following the destruction of the World Trade Towers in 2001, the U.S. launched a worldwide counterattack on al Qaeda. Two years after the attack on Cole, the suspected ringleader of the attack, Abu Ali al-Harithi, was killed by a missile fired by an American Predator unmanned aerial vehicle in the Yemeni desert. Another ringleader was captured and is in custody.

An American admiral, who had commanded Cole’s original sister Arleigh Burke, praised Lippold and his crew:

That captain obviously trained his crew to survive and thrive in the chaos . . . at the very instant the bomb exploded. There is no higher praise for a captain.

That well-trained crew, Cole’s men and women, obviously saved their ship despite losing some of their shipmates. There is no tougher fight, and there is no tougher crew than one that saves a ship.

Last but not least, we should not forget the brilliant American designers, engineers, and shipbuilders who built . . . “505 feet of American fighting steel.”

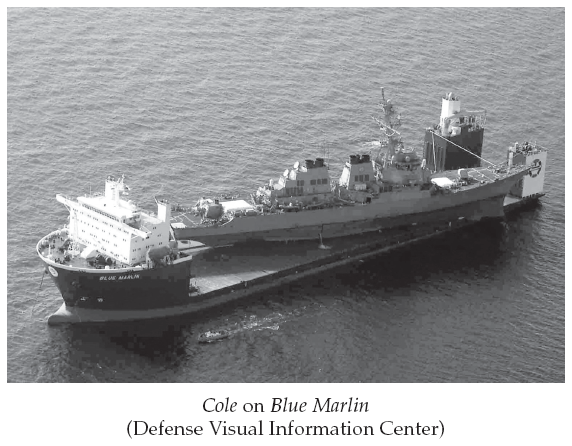

Two hundred of her crew stayed with Cole until the end of October, when she was towed out of Aden harbor flying a huge American flag and playing “The Star-Spangled Banner,” “America the Beautiful,” and Kid Rock’s popular “Cowboy.” As the American ambassador said: “[Cole] left with some help from her friends, but she left proudly.” After Cole was loaded aboard the huge Norwegian ship Blue Marlin for the long trip back to the Ingalls shipyard in Pascagoula, the crew that had remained with Cole flew home together back to their waiting families in Norfolk. As Captain Lippold said, they “return[ed] home as one crew, forever bonded by this experience.”

Following a thorough investigation, Admiral Vern Clark, chief of naval operations, sent a message to the fleet:

This is the first successful terrorist attack against a navy ship in modern times . . . the world is full of risk and there are those who are determined to bring harm to America and America’s navy. . . . The actions of Cole’s crew immediately following the blast are highly commendable. Undoubtedly through their discipline, training, and courage they saved their ship and many of their shipmates. Without the efforts of every member of USS Cole, this tragedy could have been much worse. Under the harshest of conditions, they persevered through devastation and horror that many of us have never seen. They saved their ship and the lives of many of their shipmates. Their service is a wonderful example to us all.

Cole arrived back in Pascagoula in December 2000. Chief Larson, who remembered many of the shipyard workers from 1995 when the ship was being built, stayed with Cole offering advice on reconstruction for several months until he was given another assignment. On April 19, 2002, hundreds cheered as she sailed out of Pascagoula after a repair that cost $250 million and included new engines and other upgrades. At the end of April she was back in Norfolk, although only forty sailors who had been aboard in Aden were still in her crew. Cole now has a “hall of heroes” with seventeen stars embedded in the passageway, and as the father of nineteen-year-old crew member Lakeina Monique Francis said of his dead child: “My daughter is part of the ship.”

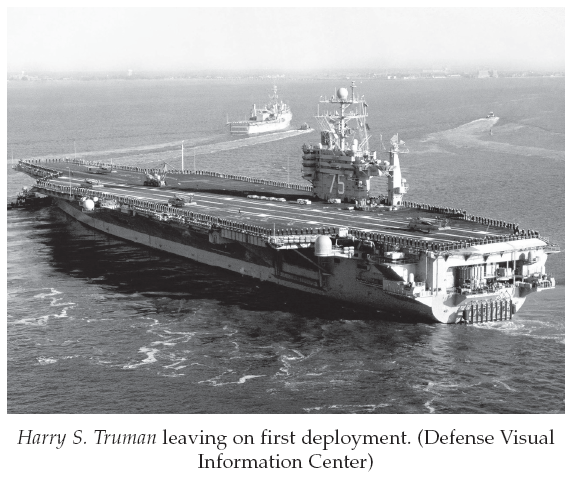

A month after the wounded Cole was towed out of Aden harbor to begin the long voyage home, families gathered in Norfolk to watch Harry S. Truman and her battle group depart for a six-month deployment to the Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf. Sad that their sailors and marines would be away from home at Christmas, they also worried for the safety of their loved ones. As one wife said: “I know this is the mother ship and she’s very protected . . . but its hard not to be concerned, especially with current events.” The battle group commander, Rear Admiral James D. MacArthur Jr. tried to reassure the families: “our sailors and marines have worked hard and trained harder over many months. . . . Our people understand the importance of our mission and are prepared to meet any challenges we may face.”

Harry S. Truman left Norfolk on November 28, 2000, but on their way to the Middle East the crew received an early Christmas present when they were visited by astronaut John Glenn, Secretary of Defense William Cohen, and a group of football stars and entertainers who broadcast Fox TV’s “NFL Live” football show from the flight deck. Star quarterback Terry Bradshaw was even taught to steer the carrier, and the Dallas cheerleaders and the pop singer Jewel performed for the crew in front of a huge portrait of Truman on the hangar deck.

As soon as Harry S. Truman reached the Persian Gulf, her pilots joined the patrols enforcing the “no-fly” zone in southern Iraq, and her small escort warships helped prevent smugglers from violating United Nations economic sanctions against Iraq. Ever since the end of the Gulf War in 1991, Saddam Hussein had been threatening allied pilots. On February 16, 2001, in the heaviest air attacks in two years, Harry S. Truman aircraft attacked Iraqi air defense radars and command and control centers near Baghdad. The pilots used 1,500 pound satellite-guided “Joint Stand-off Weapons,” which cost as much as $750,000 each and can be dropped as far as 40 miles from their targets. To their disappointment, as many as half of these very sophisticated and expensive bombs missed their targets. The navy decided that the computers in the bombs had been improperly programmed, but the unexpectedly poor performance of these costly weapons led to sharp criticism in American newspapers. Just a month later, another Harry S. Truman pilot was involved in a tragic accident in Kuwait. On March 12, an F/A-18 Hornet pilot was practicing close air support to ground forces. His bomb fell short of his target, killing five Americans and a New Zealander and wounding five other soldiers. During a speech at the time, President George W. Bush called for a moment of silence and noted: “I’m reminded today of how dangerous service can be.”

By the summer of 2001, Harry S. Truman and her battle group were back in Norfolk, but the pace of training continued. Each time the carrier returns her pilots fly their aircraft to nearby naval air stations where the airplanes are inspected, maintained, and repaired, and where the pilots spend their shore time perfecting their skills. The carrier herself is restocked for her next deployment, and new crew members are trained and integrated into the Harry S. Truman team. During their time in Norfolk the battle group makes brief training cruises into the Atlantic and Caribbean. During one such cruise during the summer of 2002, former president George H. W. Bush came aboard for an overnight visit. Watching night landings and takeoffs, the most dangerous activities on any carrier, the former World War II carrier pilot said: “What I saw on the flight deck was teamwork. . . . It was unbelievable. The ship has a soul . . . a spirit.” In December 2002 Harry S. Truman again left Norfolk, headed for another war against Iraq.

For over one hundred and seventy-five years, the soul and spirit described by President Bush has motivated the American sailors serving in Missouri ships. Whether protecting American diplomatic and economic interests, or fighting the nation’s enemies, the ships have carried the Show-Me spirit and the American flag around the world. The first St. Louis confronted a great European empire, the second helped save the Union itself, and a later St. Louis fought from the first day of World War II until the very end. The war ended on the deck of the “Mighty Mo,” and the last battleship in history fought in the last world war, the first war of the Cold War, and the first war of the post-Cold War world. The three latest Missouri ships, Jefferson City, Cole, and Harry S. Truman, face new threats and new enemies in a new century in which danger no longer comes from rival great power navies. Despite their great power, these new ships must exercise this power with unprecedented precision. Jefferson City can carry special operations SEAL teams who use stealth to reach their targets. Both Jefferson City and Cole can use their Tomahawk guided missiles against small targets hundreds of miles away—whether they are terrorist camps, radar sites, or weapons factories. And Harry S. Truman can bring the overwhelming power of her air wing to bear against terrorists or hostile countries almost anywhere on earth. All three ships should continue to serve for decades, reminding new generations of sailors of Missouri’s contributions to American naval history.