Rarely can the onset of an astounding intellectual endeavor actually be located. The first collaborations between artists and scientists, however, can. They began in the early 1960s in lower Manhattan, in the vicinity of Fourth Avenue and East Tenth Street, in the East Village, a dilapidated area full of run-down tenements. It was Picasso’s Montmartre transported to New York. The art critic Harold Rosenberg described it as the cradle of the new American abstract art, which was, as he pointed out, “the first art to appear here without a foreign address.” Its stars were the de Koonings (Willem and Elaine), Mark Rothko, Joan Mitchell, Philip Guston, Robert Motherwell, and Angelo Ippolito.

East Tenth Street quickly became the new bohemia, the locus of the avant-garde, with happenings, impromptu jazz sessions, poetry readings, performance art, and discussions on just about anything and everything, including emerging styles of art and philosophies. Newcomers with nothing to lose opened small art galleries. The Brata Gallery on East Tenth hosted Jack Kerouac’s first poetry readings, while the Tanager Gallery was lucky enough to exhibit Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

All this was done on the fly, almost haphazardly, attended by those who were “around,” as the saying went in New Yorkese, or who were attracted from elsewhere in the city by the magnetism of this déclassé neighborhood which, in any other context, would have been a no-go area. As in Montmartre at the time of Picasso, you went slumming. But in this magic domain there was freedom of thought, of action, of living—ideal conditions for the birth of new art movements such as Abstract Expressionism and its response, Pop Art, championed by Rauschenberg and Johns.

The improbable catalyst for all this was an electrical engineer from the Bell Telephone Laboratories at Murray Hill, New Jersey, called Billy Klüver.

The bohemian engineer: Billy Klüver

In early 1960, an unlikely-looking pair of men were to be seen driving a Chevrolet convertible around the New Jersey garbage dumps, scavenging. Both were in their mid-thirties and European. One was tall with a long face reminiscent of the existentialist Albert Camus, with a cigarette firmly fixed between his lips and a Swiss accent. The other was smaller and neater, with a distinct Swedish accent. They collected scraps of old metal, bicycle parts, baby carriages, and other garbage. Later the Chevrolet reappeared in Manhattan, where the two heaved their load of garbage over the fence (lower in those days) into the sculpture garden of the Museum of Modern Art.

The result of their efforts was an explosive work that literally shook the New York art scene. It was called Homage to New York and, with a nod to that great and ever-changing city, was designed to self-destruct, which indeed it did in spectacular fashion. As for the two scavengers, one was the anarchic Swiss artist Jean Tinguely. His co-conspirator was an electrical engineer taking time off from his day job at Bell Labs: Billy Klüver. So who was this bohemian engineer?

Charismatic, with a high, domed forehead and receding hairline, Klüver was born on November 23, 1927, in Monaco, as Johan Wilhelm Klüver. Of Viking stock, the child of Swedish and Norwegian parents, he grew up in Stockholm where, in 1951, he graduated from the Royal Institute of Technology. He had two passions: electrical engineering and Swedish avant-garde cinema. In fact, he was president of the Stockholm University Film Society. In his senior thesis he combined the two by convincing his thesis supervisor, the Nobel laureate physicist Hannes Alfvén, to let him make an animated film showing how electrons move through electric and magnetic fields, a phenomenon on which Alfvén was an expert.

Klüver’s interest in film was fueled by two friends, Pontus Hultén and Claes Oldenburg, both of whom would go on to have distinguished careers. In 1953, Hultén joined the Moderna Museet, Stockholm’s museum of modern art. Seven years later, he became its director and began transforming it into one of the world’s leading museums. Oldenburg’s sculptures are known worldwide.

Shortly after graduating, Klüver moved to Paris where he worked for Thomson-Houston, a subsidiary of General Electric, as a nuts-and-bolts engineer. His projects included improving the antenna on the Eiffel Tower and designing underwater cameras for Jacques Cousteau. But America beckoned. His dream was to get a job at Bell Labs.

When American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T) created Bell Telephone Laboratories in 1925, they envisaged it as a mecca for invention and also discovery. Early on in its existence, in 1927, the physicists Clinton Davisson and Lester Germer were working on a project exploring the structure of crystals using electrons when they noticed a peculiarity in the data. They had actually substantiated the schizoid nature of the electron as both wave and particle, for which Davisson won the Nobel Prize. Then in 1947, John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley invented a powerful amplifying device using solid-state materials, thus avoiding cumbersome and fragile glass vacuum tubes. This was the transistor, for which all three won Nobel Prizes. In 1965, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson were puzzled by a noise in an antenna they were debugging. The noise seemed to come from everywhere, and persisted after all defects had been eliminated, including pigeon droppings. What they had discovered, as astrophysicists at nearby Princeton University informed them, was the echo from the Big Bang, 13.7 billion years ago; they were listening to the creation of our universe. More Nobel Prizes came. Claude Shannon went on to discover information theory at Bell, where he did his best thinking while riding his monocycle down one of the lab’s long corridors and juggling three balls at the same time. Ken Knowlton, who also worked at Bell Labs, was one of the pioneers of computer art. Except for the transistor and Shannon’s work, these discoveries had nothing to do with telephones.

As a place for making discoveries and inventions, fostering creativity at its highest level, it was inherent in the Bell Labs culture that great advances necessarily involved massive failures. Klüver, later, liked to point out that at Bell Labs, any scientist who didn’t have a 90 percent failure rate with his experiments was no good. This adventurous, go-for-broke, anything-goes outlook served him well.

In 1954 Klüver was eager to join Bell Labs which was then one of the most innovative, exciting places for a scientist to work, and was certain he could get a position there. But the McCarthy hearings were going full steam, and foreigners at research centers were under scrutiny as security risks. So Klüver decided to lie low, and instead enrolled in the PhD program for electrical engineering at the University of California, Berkeley. Extraordinarily, he completed his degree in just over two years on a research topic that included theory and experiment, although he always said he preferred the hands-on approach of engineering over the theoretical side.

Afterward, he spent a year teaching at Berkeley. By this time Joseph McCarthy had been thoroughly discredited and Klüver was able to obtain the position he coveted at Bell Labs, the proper place for someone of his restless mind-set. He started off by exploring sound amplification devices as well as the possible uses for lasers.

By now Klüver’s old pal Pontus Hultén had become an eminent curator. With the help of his introductions, Klüver made inroads into the East Village art scene, with its almost famous artists and almost famous taverns and coffeehouses populated by theorists like Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, who announced the onset of new movements and decided who the famous artists were. There was always an accompanying bevy of beautiful women. But Klüver wanted to do more than just hang around. He was interested in working with artists and bringing technology and art together—blurring boundaries. His passion for this quest had been fired some years earlier by C. P. Snow’s electrifying 1959 Rede Lecture, “Two Cultures.”

Trained as a chemist, Snow was also a novelist, gaining notoriety for his whodunits in university settings, and had held several senior civil service positions. After the war, he set himself the task of assessing Britain’s future. It lay, he concluded, with science and technology, which offered hope and progress, whereas he saw the humanities as mired in the tragic condition of humankind. But they seemed to be diametrically opposed: scientists and engineers were woefully misinformed about the arts, and humanists (which included artists) were even more poorly informed about science. This would not do, especially in a postwar world driven by science and technology.

Klüver’s utopian vision was to remove the boundary between science and the arts. As an engineer at Bell Labs, and using his connections in the art scene, he believed he could do it. He was a very unusual sort of engineer.

As a preliminary, he set up an art and science club at Bell Labs, telling his colleagues that it would make them better engineers. Sadly it “never went anywhere,” he recalled.

Klüver’s big break in his quest came when he met Tinguely, a well-established resident of the New York art scene. Tinguely’s specialty was mechanical contrivances, usually made up of parts he collected from junkyards, powered with engines. To him, paintings were mere petrified objects.

Tinguely was a neo-Dadaist to the core. In 1960 he was working on his latest project, Homage to New York, in which he wanted to express his disgust with consumerism, materialism, and what he saw as a world gone amok with possessions. It was to be a slap in the face of fastidious cuckoo-clock Swiss technology.

Klüver came along just when Tinguely had begun thinking about this work, which was to become his most famous act of destruction. Homage to New York was an extraordinary contraption, a weird assemblage of small machines that would self-destruct one by one at preset times, sparking and smoking to an accompanying musical sound track while it rolled around haphazardly until it completely blew up in, as Klüver put it, “one glorious act of mechanical suicide.”

Tinguely’s problem was how to include the timers that would initiate the contraption’s destruction. Klüver had the know-how. He also had a car, which put him in a privileged position among Tinguely’s entourage. He and Tinguely scrounged suburban garbage dumps: years later, Klüver recalled the “stench sticking to your clothes. I can still smell it.”

Tinguely also introduced Klüver to his friend Robert Rauschenberg. Klüver couldn’t believe his luck. Not only had the avant-garde art world of New York opened up to him, he was working with two internationally acclaimed artists. Rauschenberg, much of whose own work also emerged from parts found in the street and junkyards, decided to come in with Tinguely, and the three men worked together.

Everything was ready by March 17 when the contraption was to perform its act of self-destruction in the sculpture garden of the Museum of Modern Art. Rauschenberg’s contribution, dwarfed by Tinguely’s, was entitled Money Thrower. It was a box filled with gunpowder and holding a dozen silver dollars. When the box exploded, the dollars would catapult into the crowd.

Everything was set. The performance, scheduled to last twenty-seven minutes, was witnessed by a chic invitation-only audience. As a reporter described it:

During its short life, this artful contraption, programmed for a symphony of suicide, sent out smoke flashes, rang bells, played a piano with mechanical arms made of bicycle parts, poured gasoline on itself, set itself on fire, crushed bottles filled with evil-smelling gas, turned on a radio, spilled cans of paint on rolling scrolls, threw out silver dollars, melted its supports, sagged and nearly collapsed. The machine was supposed to have crawled to the museum pool and thrown itself in, but it didn’t. . . . It was a direct and delightful assault on the belief that all art must be “lasting.”

In the end, nothing went according to plan. The various timers did not detonate the charges on schedule. Rauschenberg’s device, set to go off at a certain point in the program, exploded at an entirely different time.

“Art Goes Boom,” was the New York Journal-American headline. The fire department had to be called in to douse the flames. The crowd loved it.

Tinguely was unperturbed. Klüver was in his element. Making mistakes was the credo of Bell Labs. Mistakes—or, better, unpredictability—became a part of performances based on technology. Expect the unexpected, was the byword.

Much of Homage had been built with Bell Labs equipment and in Bell Labs time. The day after Homage went off, Klüver’s supervisor, John R. Pierce, barged into his office. Klüver assumed he was about to be fired. Instead Pierce demanded, “Why wasn’t I invited?”

When asked to describe his art, Rauschenberg liked to say that he worked “in the gap between art and life,” using everyday objects. He called these works “combines.” He was inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s legendary Fountain of 1917, a nonfunctioning upside-down urinal signed “R. Mutt,” the precursor and epitome of Dada, the nonrational, nonconformist art movement in which it was the concept or idea that mattered, not the object, and which had completely transformed art. For Rauschenberg, a typical day began with an early morning stroll looking for junk. Often his assistants would widen the search beyond his immediate neighborhood.

In this quasi-realistic manner he explored the cosmos. But leaving it completely, which was what he interpreted Abstract Expressionism as doing, was not to his taste. Rauschenberg was a proponent of Pop Art, which would displace Abstract Expressionism from the art hierarchy while retaining its abstract meaning, in that Pop Art works were interpretable, if at all, only through signs, the subject matter of semiotics. Rauschenberg’s work with Klüver opened up the possibility of using technology to put his ideas in motion. He wanted more. “I met Billy Klüver, the Bell Labs physicist,” he recalled, “both here and in Sweden. He gave me the suggestion that the possibilities in technology were endless. Of course he was right. It was a difficult transition to make because I normally work very much by hand. I rely on the immediate sight and actuality of a piece. Moving on to theory and its possibilities was like being handed a ghost bouquet of promises.”

Just days after Homage to New York, the two ran into each other at an exhibition of the Spanish artist Antonio Tàpies. Tàpies’s decontextualized style bore similarities to Rauschenberg’s, so it was no surprise that Klüver had shown up as well. The two decided to collaborate.

Rauschenberg had in mind a complex interactive piece that would respond to the viewer’s movement, the ambient temperature, and light. In Klüver’s opinion, the state of technology was not up to this. They decided to break it up into components. Several times they put together complete technical systems, then junked them. After more than three years of work, the final product was ready. Rauschenberg called it Oracle.

It was made up of five sculptures constructed from material found in the street: a rough bathtub with shower, a staircase, a window frame, a car door, and a pipe, fused together with galvanized sheet metal and mounted on casters. Inside each was an AM radio controlled by a central unit in one of the sculptures which acted like a command center. Rauschenberg didn’t want any wires between the sculptures. This was where electrical engineering came in, in the innovative use of transmitters, receivers, amplifiers, and speakers. Klüver designed the command center that controlled the electronics, using fully transistorized FM wireless microphones, state-of-the-art technology at the time. The radios continually scanned all five available stations, producing a chance mélange of sounds—unpredictability. What emerged, Klüver recalled, was a “collage of ever-changing bits of music, talk and noise—loud, soft, clear or full of static,” as random as the sounds heard floating from apartment windows on a walk through the Lower East Side. It was a multidimensional, multidisciplinary conglomeration of installation sound art.

Oracle had its debut in the cutting-edge Leo Castelli Gallery in May 1965. Only Rauschenberg’s name was on it, not Klüver’s. Reviews were uniformly excellent. The critic Lucy Pippard noticed that one of the five sculptures was the “most crowded and most business element; it lacks the absurdity of the other four and is the least individually beguiling.” This was the one Klüver designed.

Rauschenberg went on to win the Norman Wait Harris silver medal and prize in 1968. Oracle is now on permanent display at the Pompidou Center in Paris. Unpredictability even broke into the work’s installation for the grand opening there in 1977. As Klüver described it:

Rauschenberg arrived and we worked frenetically to get Oracle going. An hour before the official opening, we plugged in the pump motor for the shower and blew all the fuses in our section of the museum. The electricians had all gone home for the day, and no one knew where to find the fuse box. When minister of culture Michel Guy and museum director Pontus Hultén arrived with President Giscard d’Estaing and Princess Grace, we were standing in semidarkness. The sound from a few lonely radio stations could be heard from Oracle, and with the refrigeration coils inoperative, the congealed fat was slowly melting—and creating a bad smell—in Joseph Beuys’s piece Plastischer Fuss, Elastischer Fuss nearby.

Klüver’s message was: no technology, no work of art. To ram it home, he insisted that the “technical elements involved in [these] works are just as much a part of the work of art as the paint in the painting.” He continued, “The artist could not complete his intentions without the help of an engineer. The artist incorporates the work of the engineer in the painting or the sculpture or the performance . . . Technology is well aware of its own beauty and does not need the artist to elaborate on this. I will argue that the use of the engineer by the artist is not only unavoidable but necessary.”

The year 1966 was a watershed in his life. His supervisor’s enthusiastic response to Homage reinforced his determination to collaborate with artists. He “felt it was a positive use of time.” Besides Tinguely and Rauschenberg, Klüver went on to work with Andy Warhol, on Silver Clouds, metalized plastic film filled with helium and oxygen that wafted about Leo Castelli’s gallery that year; John Cage and Merce Cunningham, in their production of Variation V, in which the dancers’ movements triggered sounds and lights; and Jasper Johns, for whom he inserted battery-powered letters as lights into a painting.

Klüver insisted that technology pervades our existence. A favorite example of his was the space program in which, so he said, it was sometimes difficult to know where the machine ended and the human being began. What was needed was the elimination of human error, a “new and maybe inhuman objective.” At the time, many found it astounding that technology in the form of electronics and computers was being applied everywhere and seemed to promise improvements in growing food and providing shelter. Klüver liked to quote Marshall McLuhan, the self-proclaimed philosopher of communication theory: “Technology is the extension of our nervous system.”

2.1: Variations V (1965). John Cage, David Tudor, Gordon Mumma (foreground); Carolyn Brown, Merce Cunningham, Barbara Dilley (background). Photographer: Hervé Gloaguen.

Perhaps, Klüver believed, he could achieve the dream fired by his reading of C. P. Snow: to remove the boundary between engineering and the arts in a way that benefited both artist and engineer, both of whom were essential for a true art-technology project. Klüver went even further: “I’m not so much interested in helping artists as I am in seeing what effect the artist could have on technology. In the future, I see the artist having more and more impact, as he learns more and more about technical processes.” Artists should create using technology because it is an inherent part of our lives.

“The artist’s work is like that of a scientist. It is an investigation which may or may not yield meaningful results. . . . What I am suggesting is that the use of the engineer by the artist will stimulate new ways of looking at technology and dealing with life in the future.” Like engineering, art was research, and both art and engineering achieved their fullest promise when the two worked hand in hand. Picasso, who was deeply influenced by the mathematics, science, and technology of his day, wrote similarly that “my studio is a sort of laboratory.”

Klüver only occasionally used the word “science” alongside “art.” In the passage above, this was a slip. He was quite explicit about this. Referring to an organization he was to form later that year, Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), he wrote, “Many people wanted E.A.T. to be about art and science, but I insisted it be art and technology. Art and science have really nothing to do with each other. Science is science and art is art. Technology is the material and the physicality.” Julie Martin, Klüver’s wife, told me that he often said, “What do an artist and a scientist have to talk about? But it’s different with an engineer.” With an engineer there could be something concrete, something hands-on.

The time had come for a major collaboration between artists and engineers.

Most of Klüver’s colleagues had had no contact at all with the art community—or art for that matter, as Leonard Robinson, a fellow engineer at Bell Labs, humorously noted: “When I heard last May that we were going to Rauschenberg’s I thought it was a Jewish delicatessen. That’s how much I knew about art.” Starting in summer 1965, Klüver, buoyed by encouragement from Bell, enlisted thirty of his colleagues to work with ten artists.

While Klüver extolled the virtues of working with artists, saying that it would make one a better engineer, Herb Schneider, a colleague, suspected there was another reason: “I watched Billy having fun with the artists. Billy was the link between Bell Labs and the artists. They were disorganized, but having a ball.” Indeed, it was a great way to get away from suburbia and into the throbbing, swinging Greenwich Village art scene. Some engineers were never the same again.

At first, the artists and engineers met at Bell Labs. Senior figures such as John Pierce were behind the project, but nevertheless they insisted that the meetings be held late in the evening, well outside company time.

Klüver was concerned that the first meeting might not go well. In fact, everyone found it stimulating, although the artists began asking for technical miracles well beyond what the engineers could offer: walls made of warm air, materials that would decay and disappear during a performance, televisions that could revert to slow motion and back, balloons coming out of a hat like thought balloons, floating forms following people around, laser beams that could write on surfaces, artists suspended in midair, and large mirrors with continually changing curvatures. The artists appreciated that these ideas might not be possible, but it was a way to get the ball rolling.

The engineers replied with explanations that were far too technical. The problem was, they lacked a common language.

Herb Schneider was at first skeptical of these collaborations and then became a zealot: “At first artists were in control—nothing worked. They threw ideas to engineers expecting them to fix everything, but engineers could make no sense of what they wanted.” So Schneider stepped in as translator. John Pierce also took an active role in the early deliberations, as did Manfred Schroeder, director of Bell’s acoustics, speech, and mechanical research lab. After much discussion, the team agreed on various projects. Several weeks of rehearsals followed in a school gymnasium in New Jersey. The event was to be called 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering.

First, they had to choose the venue. Rauschenberg wanted a huge space to house the expected large audience. Radio City Music Hall and Yankee Stadium were suggested. Then Seymour Schweber, head of Schweber Electronics, one of the sponsors, suggested the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue. He recalled the “nostalgia that surround[ed] it because of the original Cubist show in 1913 when Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase was exhibited and knocked the critics off their rockers.” He believed that 9 Evenings would represent a similar breakthrough, “affording the audience a taste of future shock.” That had to be it.

In the event the staging was amateurish; no one had experience with a space of that size. Armories are cavernous. The Swedish multimedia artist Öyvind Fahlström, one of those involved, described it as more like a turn-of-the-century railroad station. The 69th Regiment Armory is 162 feet high with no facilities for attaching lighting equipment. Due to its size and the height of the ceiling the acoustics were terrible, added to which radio reception was not good and many stations were not available. Then the lighting expert became ill and had to be replaced by an inexperienced substitute. No one had any idea how much light would be needed to fill the space. Scaffolding had to be specially built to support the weight of 5,000- and 10,000-watt lights because the balcony railing was too weak. To add to all this, the team had seriously underestimated the equipment rental budget. And there was no production manager to handle staff and dismiss incompetents.

The Bell engineers worked huge hours for no pay and, says Cecil Stoker, one of the engineers, “their unhappy wives frequently came down to the Armory, children in tow, and made scenes.” Klüver soldiered on.

But collaboration often broke down. While the artists told the engineers what they wanted and the engineers did their best to provide it, they did not easily understand each other. Finally Schneider realized that the common language of the engineers and artists was visual imagery, maps of their ideas: pictures, not words. He created wiring diagrams that both could understand and which were then turned into plugboards for electronic circuits that controlled lights and other equipment.

Least collaborative of all the artists was the composer John Cage, who “just said what he wanted,” as Klüver’s wife recalls, although he, too, pitched in at the end. Classically trained, for over twenty years he had experimented with how to mix Dada and Buddhism with music. One of the most influential composers of the twentieth century, he set out to fracture the smooth flow of music into staccato bursts, often using new versions of instruments, such as a piano which he rejigged into a percussion instrument by inserting objects between the strings. He also pioneered the use of variable-speed turntables, in today’s DJ style, as well as audio-frequency oscillators. Cage concluded that any sound—including silence—could be music.

Before the performance Klüver wrote a “for your eyes only” memo to the engineers. Here are his notes on Cage and Rauschenberg:

John Cage: . . . Cage makes definite decisions about what he wants and what he does not want. The appearance before the concert is usually a big mess of equipment and wires. If something does not work it is okay. . . .

Robert Rauschenberg is easy to work with. He will tell you exactly what he wants. His piece will probably not be ready until the first performance. If you have suggestions for him he will tell you if he likes them or not. It is great to watch him make choices. He will need a lot of help/the trouble is he looks like he does not need help, but that is not true. Due to his fame his piece will have great publicity value and every effort should be made to make it a success. He appreciates very much what you do for him.

At the end of his memo, Klüver urged engineers to reassure the artists that everything would work. They should make it clear that “We handle the technical end and they are not to worry about it. . . . If there are any problems, tell me about them rather than letting them interfere with the show.” “Good luck,” he concluded, as if laying the plans for a military campaign.

The engineers did their best to reassure the artists, though they must have had a tough time. As one engineer recalled, “Fuses were blowing like mad, weird flashes of sound and light would burst into the gym, occasionally the acrid smell and smoke of a burned out resistor would fill the air. But never did the engineers express doubt in front of the artists.”

The advertising agency for the show was Ruder and Finn, Inc., aided by the artists and their friends, who spread the word that something fantastic and momentous was about to occur. Ruder and Finn divided the events into theater and concert pieces, promoting the show as avant-garde theater, a happening in which the audience would be welcome to participate. 9 Evenings opened with a bang on October 13, 1966. Newsweek wrote on October 31:

Half a millennium ago Leonardo da Vinci agonized over his attempt to integrate the logic of science and the inspiration of art. Things are better today—only recently a physicist spoke on the reversibility of time before a scientific meeting while playing the bongo drums. Or are they worse? In any case, today is today, and engineer Billy Klüver recalled the bongology incident last week as he introduced the largest and most organized attempt yet by artists to arm themselves with the ravishingly efficient implements of science.

The “bongology incident” was a lecture by the physicist Richard Feynman, which he enlivened by playing the bongo drums. The Armory event was a reversal of Feynman’s anarchic act: artists armed with “implements of science.”

For his piece, Cage and his crew moved around long tables jammed with electronics, playing with a collage of sounds collected by a bank of telephones from remote sources such as the ASPCA, restaurant kitchens, and police and marine radio channels, filling the Armory with random noises. Cage had wanted sounds from outer space as well. He might have had them, thanks to Penzias and Wilson’s picking up an echo from the Big Bang just the previous year. During the opening night performance, a stagehand happened to see some telephones off the hook and hung them up. Silence ensued until the connections were reestablished. This was one silence Cage didn’t want.

In his Open Score the following night, Rauschenberg used state-of-the-art electronics to subvert a game of tennis. Radios inside the racket handles transmitted sounds which were amplified by speakers suspended by wires secured to the ceiling. The two players were the artist Frank Stella and the tennis pro Mimi Kanarek. Every time they hit the ball a light went out until there was total darkness. Individual members of the audience on the Armory floor were illuminated by infrared-sensitive television cameras and the images were projected onto three large screens. The audience was aware of the size of the crowd only through these projections.

The enthusiastic advertising campaign had led the audience to expect polished performances with no glitches. But this could never have been, owing to the vastness of the Armory and the lack of a production manager. It was the newness of it all. 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering was experimental. It was a collaboration between two groups of people who at first sight were poles apart, trying to accommodate each other, to think along common lines, and to do something that had never been attempted before.

The critic Brian O’Doherty rightly argued that technological malfunctions did not equal artistic failure:

[9 Evenings] received, on the whole, an appalling press—based mainly on the justifiable irritation of interminable delays, technical failures of the most basic sort, and long, dead spaces between, and sometimes in the middle of, pieces. Yet, as such irritations faded away, one is left with startlingly persistent residual images, and strong hints of an alternative theater that has been lagging in its post-Happenings penumbra between art and theater.

“Happenings” were impromptu performances in which the audience participated. They were unpredictable, unique, sometimes wild, and occasionally dangerous. The best moments usually arose when something “went wrong.” The first took place in the 1950s and they were a key part of the countercultural 1960s’ scene. One of the most notable was a performance by Yoko Ono in Tokyo in 1964, when she appeared onstage swathed in fabric, presented the audience with a pair of scissors and invited them to cut the fabric away. As O’Doherty suggests, by 1966 happenings had probably passed their peak. 9 Evenings had all their spontaneity and inspired anarchy.

With time, 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering has come to represent an inspired moment in the new combination of art and technology. The mechanical age was over. The electronic age had begun.

A call to arms

It was in the air in the 1960s: artists seeking to bridge the gap between art and technology. Klüver spoke of “a new mode of interaction between science and technology on the one hand and art and life on the other. To use a scientific jargon that is currently in, I will try to define a new interface between these two areas.” There had been sightings years before, ever since the coming of movies—an art form that emerged directly out of artists’ interest in technology. Already people were pointing out that in order for a collaboration to be meaningful, the artist would have to be technologically literate, perhaps even a trained engineer, which was a bit of a stretch at that stage. Bell Labs opened their computer facilities to musicians who wanted to learn programming, a fairly basic tool; the revered avant-garde composers Edgard Varèse and Milton Babbitt were among the first to use them.

Klüver was eager to create an organization that would catch the swell of the tidal wave of collaboration between artists and engineers. Shortly before the first performance of 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering, he had met with Rauschenberg, Robert Whitman (an artist who had been involved in some of the earliest happenings), and Fred Waldhauer (an engineer at Bell known for his work on hearing aids). His aim was to ensure that whatever momentum was generated by 9 Evenings would not be lost. The four founded Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), with Klüver as president, Rauschenberg as vice president, Waldhauer as secretary, and Whitman as the treasurer.

E.A.T.’s first meeting was at the end of November 1966. Klüver’s wife, Julie Martin, recalled that three hundred people attended—mainly artists and engineers, all of whom “expressed huge interest. Sixty people had questions right away.”

In a newsletter of June 1, 1967, Klüver and Rauschenberg stated that “the purpose of Experiments in Art and Technology Inc., is to catalyze the inevitable active involvement of industry, technology, and the arts. E.A.T. has assumed the responsibility of developing an effective collaborative relationship between artists and engineers.” They stressed the symbiotic effect of such a relationship. Engineers could learn from artists about the human scale of their work, while the artist would be able to continue the “traditional involvement of the artist with the relevant forces shaping society.”

On October 10, 1967, the team held a press conference at Rauschenberg’s spacious three-story studio to “formally launch E.A.T. to the public and press and to ask for support from industry, labor, politics, and the technical community.”

Among the speakers was John Pierce of Bell Labs, an early advocate of all that Klüver was trying to accomplish and an active participant in E.A.T. He began, “Technology is the source of the material well-being of our age. Man cannot live without art. Sometimes it seems that our culture and our lives are becoming fragmented. I am happy that dedicated and talented people are bringing art and technology together through experimentation, which is a common ground for both.”

Invoking, or perhaps rediscovering, Immanuel Kant, he went on, “Surely, art cannot safely ignore or reject such a powerful force as technology. And technology should not be without art.”

Among the political heavyweights who spoke were Senator Jacob Javits of New York and Herman D. Kenin, representing the powerful AFL–CIO union. In those days there were considerable misgivings that machines were going to take over the world and put millions out of work. Kenin provided the endorsement Klüver needed, making a speech extolling the benefits of computers. E.A.T.’s board of directors included Alfred H. Barr, founding director of the Museum of Modern Art; John Cage; Senator Javits and his wife, Marian; the architect Philip C. Johnson; György Kepes, the Hungarian-born artist, designer, and art theorist who had established the Center for Advanced Visual Studies, incorporating art, science, and technology, at MIT that same year; and Marie-Christophe de Menil of the Houston art-collecting family. E.A.T. was on its way.

To round off the evening, several works of art were exhibited, including Rauschenberg’s Oracle, Warhol’s Silver Clouds, and one of the first computer-generated works of art, Studies in Perception I. The last had nothing directly to do with E.A.T. but had been produced at Bell Labs by two of Klüver’s colleagues, Ken Knowlton and Leon Harmon, both specialists in the then young field of computer graphics. Knowlton was already sure that his future lay in art. “The nonscientific, some say artistic, aspects of computer graphics arose for me via a sophomoric prank,” Knowlton said. In 1966, he and Harmon had come up with the idea of scanning photographs with a television camera, then converting the varying halftones to small electronic symbols. When the resulting image is viewed up close it is just a mishmash of symbols, but viewed from a distance it takes on a specific shape.

Their boss, Ed David, director of Visual and Acoustic Research, happened to be away for a few days, so they decided to hang a twelve-foot-wide picture on his wall representative of their work—“of, guess what, a nude!” Knowlton gleefully recalled. As a model, they had enlisted the twenty-five-year-old dancer Deborah Hay, who was also a friend of John Cage. They paid her $50, a not inconsiderable sum at the time. Harmon and Max Mathews, a pioneer in composing music on the computer, were at the photo session, with Mathews as the photographer.

When David returned to his office he took one look at the image and was “delighted but worried.” An unusual number of visitors came by David’s office. The upper echelons heard about the picture and wanted it removed immediately, but smaller versions of the photograph were in circulation already. The public relations department warned that “you may circulate this thing but be sure that you do NOT associate the name of Bell Labs with it.” Bearing that warning in mind, Knowlton and Harmon brazenly approached MoMA. The curators there were not particularly excited. “Interesting but no big deal,” was their response. They did, however, agree to exhibit it during a lunch hour.

2.2: Leon Harmon and Ken Knowlton, Studies in Perception I, 1966.

A year later, Knowlton and Harmon’s picture was on show in Rauschenberg’s loft at the press conference to launch E.A.T. The New York Times published the image. “Since it appeared in the venerable New York Times, it was art with a capital A, instead of porn,” says Knowlton. The public relations department at Bell Labs did an about-face and ordered him and Harmon to “be sure that people know that this was produced at Bell Telephone Laboratories, Inc.” As for their colleague Klüver, “Billy was forever retelling the story, including pointing out that it was the first time that the New York Times printed a nude!”

Another of Harmon’s research interests was facial recognition. For a 1973 article, “The Recognition of Faces,” he used a highly pixelated image of Abraham Lincoln taken from a five-dollar bill. This intrigued Salvador Dalí, who had a keen interest in the science of perception, and he based his 1976 painting Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea on it.

Flushed with the success of 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering, E.A.T. continued to bring together artists and engineers. A leaflet circulated in early 1967 announced (I leave in the misspelling to give an idea of the off-the-cuff air of the organization), “The following series of demonstrations—bull sessions—lectures by scientists and engineers is designed for artists. To stimulate the discussion and facilitate matchings, we are also suggesting the engineers attend whos field is the topic of the day.” The schedule of lectures and demonstrations for February through April 1967 included computer music, television equipment and capabilities, computer films and animation (some by Knowlton), color theory, and holography. All the lectures were sold out.

The lofty aims announced at the launch of E.A.T. seemed achievable, especially considering the success of 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering. Sadly, this turned out not to be the case. An early attempt to raise funds failed, despite the fact that artists who contributed works to the E.A.T. show at the Leo Castelli Gallery included Walter de Maria, Marcel Duchamp, Red Grooms, Donald Judd, Sol Lewitt, Robert Rauschenberg, Larry Rivers, Cy Twombly, and Andy Warhol. Like today, despite all the publicity, only a few people actually bought art.

The Ford Foundation, IBM, and AT&T all turned down grant applications for the half a million dollars which E.A.T. needed. Requests for smaller amounts were more successful, but this did not solve financial issues concerning staff and day-to-day expenditures.

There were other problems, such as safety. One of the performances in 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering involved scanning volunteers’ faces with a laser beam. When the Office of Radiation Control at the New York City Department of Health heard of this, they informed E.A.T. that they were to be notified in advance whenever lasers were used in performances.

E.A.T.’s most ambitious project was the Pepsi Pavilion at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan. The planning and building involved seventy American and Japanese artists and engineers, working together. Pepsi allowed Klüver to be solely responsible for the design. For the most part all went well, but the severe cost overruns dominated the press reports. The pavilion itself was a geodesic dome 75 feet high and 165 feet in diameter, crammed with electronics and mirrors intended to transport visitors to virtual worlds. It was decades ahead of its time.

Although interesting projects were planned, E.A.T. made the mistake of trying to include too many fields. The thrust turned away from collaborations between scientists and engineers to education and art in developing countries. Its focus moved from blurring the boundaries between art and technology to those between art and life, developing instructional television films to fight illiteracy and improve dairy production around Ahmedabad, in India. They achieved some success, but they had lost sight of their original purpose. 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering was E.A.T.’s debut and high-water mark, with the Pepsi Pavilion in a distant second place.

Jasia Reichardt, a curator with a keen interest in the cultural importance of technology, summed up the demise of E.A.T. and the importance of Klüver: “If E.A.T. faded out, it was through a natural process of decline, precipitated by developments in technology itself. Some of the technologies became easy enough for the artist to use without much technical support. Some artists made demands that could not be met. . . . E.A.T. belonged to a decade when such ambitions could be fired by the enthusiasm of one man.”

A key achievement of Klüver’s 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering was that it inspired other collaborations and events, in particular Jasia Reichardt’s own Cybernetic Serendipity.

Computers and creativity: Jasia Reichardt

In 2011, when I knocked on the door of Jasia Reichardt’s house in London, I had not seen her for over twenty years. Reichardt exudes ebullience, enthusiasm, and sweep of knowledge of the art scene. Her house is like an archive, housing material on the intersection of art and technology as well as on concrete poetry, in which words form images, together with a vast collection of books on art and art history and catalogues of exhibitions.

Reichardt made it clear that she was not an artist. Rather, she curates exhibitions, has been a gallery director, and writes about art, as well as about literature. She is interested in the “edges of things, of how art, literature, theater and technology intersect.” In 1957, she was reading about cybernetics and became intrigued by the role technology might play in art. As she put it, “Both computer art and concrete poetry belonged to art’s outer periphery.”

During World War II, engineers had learned how to build sophisticated devices for gunnery platforms that, through feeding back (“feedback loops”), could make corrections in tracking a swiftly moving target such as an airplane. Immediately after the war, in 1946, the first of the Macy Foundation conferences was held in New York, to discuss how to use such breakthroughs in peacetime. The conferences aimed to set the foundations for a general science of the human mind. One of the participants, Norbert Wiener, a professor of mathematics at MIT, had had a great deal of experience in anti-aircraft work during World War II. He used his knowledge to develop cybernetics, taking the word from the ancient Greek kyubernētēs, “to steer,” and laid the foundations of this new field in his book Cybernetics, or Control and Communications in the Animal and the Machine, published in 1948.

Cybernetics is the study of how systems self-regulate through feedback and how this relates to all domains, human and mechanical. The thermostat is an example of a cybernetic system. It is made up of two parts: a heater and a sensor. Once a temperature is selected, the sensor turns the heater on when the ambient temperature drops below the chosen temperature and turns it off when the correct temperature is reached.

To artists, cybernetics opened the possibility of art as an interactive process, an open system that includes material objects (possibly interacting among themselves) as well as enabling the audience to interact with an artwork and change it.

In 1949, the Hungarian-born artist Nicolas Schöffer read Wiener’s book and was stunned by the possibilities it suggested. “[Cybernetics], for the first time, makes it possible to replace man with a work of abstract art,” he said. Five years later, he began producing majestic artworks, beautifully crafted, incorporating its principles. These were delicate, towering constructions made up of fine metal tubes, photoelectric cells, microphones, motors that turned rods with gears, and mirrors that caught and responded to variations in the color, temperature, and light intensity of the surroundings.

They combined complexity with beauty in movement. They were ever-changing; something new was always happening. Schöffer is now known as the father of cybernetic art.

Reichardt mulled these developments over. Then, in 1966, she heard about E.A.T. At the time, she was assistant director at the fledgling Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London. She got a travel grant from the US State Department and flew to New York, arriving in the midst of the hectic days leading up to the Armory show, and was immediately caught up in the excitement. She loved the way that Klüver ran meetings, adroitly dealing with “artists who wanted engineers to do the impossible—like artists wanted to fly. Some of the engineers all of a sudden wanted to be artists, too.” The “meetings were enthusiastic, heartfelt, and naive.” Having seen 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering, she was sure that part of the excitement was that things often didn’t work.

2.3: Nicolas Schöffer, CYSP 1, 1956.

Reichardt wanted to create something like E.A.T. in London. Then she recalled a comment made by the German philosopher Max Bense, whom she had met in 1965 when he visited an exhibition on concrete poetry which she had curated. He asked what plans she had for other exhibitions. None, she replied. Bense suggested, “Look into computers.”

“[Bense] was adept at crossing borders from philosophy to cybernetics, aesthetics to concrete poetry, physics to the theories of chance,” says Reichardt. His interests spanned the philosophy of science, logic, art, and aesthetics, and he passionately believed that the arts and the sciences should complement each other. Bense wanted to focus on what was aesthetic in computer-generated art. He called this “generative aesthetics” and tried to base it solely on objective considerations, such as mathematics and logic. He was a prime force in organizing the first exhibition of computer art in 1965 in Stuttgart, Germany. But this was overshadowed almost immediately by E.A.T. and then by Reichardt’s Cybernetic Serendipity.

Determined to do something different from 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering, Reichardt planned a show whose theme would be the relationship between creativity and technology, with the emphasis on computer art. She proposed it to the co-directors and founders of the ICA, Herbert Read, the eminent poet and critic, and Roland Penrose, the artist, art historian, and friend of Picasso. At the time, the ICA was just starting up. Located on the first floor of 17 Dover Street in London, it was short of money, staff, and space. The space problem was solved in January 1968 when it moved to its present quarters on Carlton House Terrace.

Using Read’s and Penrose’s connections, and with interest from C. P. Snow, whom Reichardt had met at a dinner party, she managed to raise £25,000 from, among others, IBM, the Arts Council, the US Air Force Research Labs, Bell Telephone Labs, Boeing, and General Motors. Individuals who provided encouragement included Klüver’s old friend Pontus Hultén; the artist György Kepes, who had founded the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT; Warren McCulloch, an early champion of computers and cybernetics; Nicholas Negroponte, the architect and founder of MIT’s Media Lab; the mathematician and computer scientist Seymour Papert from MIT; and John Pierce of Bell Labs. The staff worked long hours unpaid. The budget was large enough that the ICA even advertised on the London Tube.

The participants included computer artists and musicians, among them Frieder Nake of the Stuttgart Group; Ken Knowlton of Bell Labs; the Op Art painter Bridget Riley, who produced paintings resembling moiré patterns; John Cage; the Greek composer Iannis Xenakis, who used mathematics and architecture for composing; the roboticist Bruce Lacey; the media artist Nam June Paik; Jean Tinguely; and Nicholas Negroponte.

Reichardt called the show Cybernetic Serendipity “because it deals with possibilities rather than achievements . . . with exploring and demonstrating some of the relationships between technology and creativity . . . The aim is to present an area of activity which manifests artists’ involvement with science, and the scientists’ involvement with the arts.” The show aimed for the complete eradication of boundaries between the arts and sciences. Reichardt felt that an artist’s creative ability to use computers or robots was the most important factor in choosing them, rather than their artistic background. She wrote, “No visitor to the exhibition, unless he reads all the notes relating to all the works, will know whether he is looking at something made by an artist, engineer, mathematician, or architect.” Some artists were critical of her approach. Stephen Willats, a computer artist with a fine arts background, complained that the show was “full of scientists masquerading as artists.” But his was a minority view.

Cybernetic Serendipity was opened on October 2, 1968, by the minister of culture, Anthony Wedgwood Benn. Princess Margaret was among the guests. As Penrose emphasized at the press conference, “The ICA has always realized that the arts need to establish a very close relationship with science . . . It is our custom at the ICA to explore the mysteries of technology and wherever possible to find new uses for its utilitarian inventions which will bring us enjoyment, enlightenment, and a wider consciousness.”

Cybernetic Serendipity took London by storm. About 60,000 visitors came to have a look, and 325 artists and scientists participated. It was a landmark event. It was the first ever gallery show to exhibit robots, cybernetics, and computer art, and provided a technological feast of music, poetry, and prose composed on computers, together with computer-programmed choreography, computer films, computer paintings, computer-animated films, and experiments in ways to visualize data.

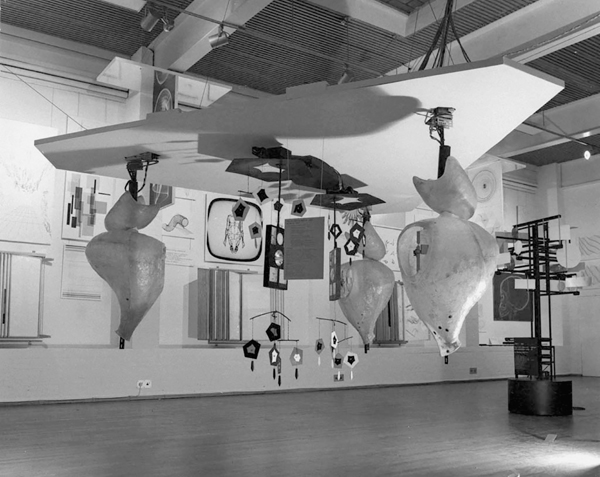

Radio-controlled robots roamed the halls, stopping to kiss the curious. A music computer improvised on tunes which visitors whistled into a microphone. One of the star exhibits was Colloquy of Mobiles by the eminent cybernetics researcher and psychologist Gordon Pask. It consisted of five rotating mobiles, three made of glass and fiberglass (“females”) and two swelling aluminum forms (“males”). When a “male” emitted a beam of light, it struck the mirror inside the “female’s” structure and deflected the light back to the “male,” suggesting a moment of mutual satisfaction. It was a demonstration of how entities could communicate and learn about each other via feedback systems using electronic signals without human intervention.

2.4: Gordon Pask, Colloquy of Mobiles, 1968.

Knowlton and Harmon’s famous reclining nude, Studies in Perception I, now renamed Mural, appeared. Knowlton’s pioneering computer animations were also shown, as was A. Michael Noll’s study of Mondrian, Nake’s line drawings, rather small and benign painting machines by Tinguely, and Schöffer’s cybernetic sculptures which responded to their environment. The show was a great inspiration to young artists. One, Ernest Edmonds, then a mathematician at City of Leicester Polytechnic, recalled that it “showed a healthy lack of concern for what exactly should be seen as art, science, or technology. It demonstrated how cross-disciplinary stimulation could encourage exciting innovation.”

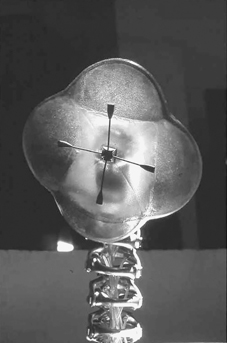

It was the interactive pieces that most interested budding artists such as Edmonds. Besides Schöffer’s cybernetic sculpture, there was Edward Ihnatowicz’s Sound Activated Mobile (SAM). Ihnatowicz was something of a legend in his day. Trained in sculpture at the Ruskin School of Drawing, Oxford, from 1945 to 1949, his interests included photography and electronics. He even built an oscilloscope, used for testing electronic apparatus, from spare parts. He started off at the BBC, then worked as a furniture designer. In 1962, when he was forty, he decided to devote himself to sculpture of a mechanical sort—pieces that moved.

There and then he left his comfortable house and his family for an unheated garage in Hackney, in the run-down East End of London. His son and his friends, fans of Jack Kerouac and Henry Miller, saw in his move “a great deal of existential romance, glamour and drama.”

Ihnatowicz got down to work, inspired by the aesthetic shapes he saw in the car parts that he cannibalized. Using spare parts, hydraulic valves from government surplus equipment, analog circuits (circuits with wires, resistors, capacitors, vacuum tubes, and transistors), and servo mechanisms (devices that compare input to output signals, providing a means of correction as in gunnery sights), he built his Sound Activated Mobile (SAM). About three feet high, it looked rather like a spine with a flowerlike head consisting of four fiberglass reflectors, each with a microphone in front of it. SAM’s circuitry enabled it to respond to sound by bending and trying to locate the source. At Cybernetic Serendipity, SAM leaned toward people talking as if it were listening. Visitors had the eerie sensation that they were being watched.

2.5: Edward Ihnatowicz, Sound Activated Mobile (SAM), 1968.

The press release for the exhibition promised “a gallery full of tame wonders which look as if they’ve come straight out of a science museum for the year 2000.” Most of the reviews concluded that the exhibition had indeed achieved its aim. Nigel Gosling wrote in the Observer, “I think we shall look back to it one day as a landmark.” The Evening Standard enthused, “Where in London could you take a hippy, a computer programmer, and a ten-year-old schoolboy and guarantee that each would be perfectly happy for an hour with you not having to lift a finger to entertain them?” The Hampstead and Highgate News added hyperbolically, “For breaking new ground, revealing new fields of experiment, seminal experience, the exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity . . . is arguably the most important exhibition in the world at the moment.”

It is important to remember that Cybernetic Serendipity sprang out of a particular moment in history. The 1960s was an era of great political and social upheaval; 1968 was the height of the protests against the Vietnam War, in which technology had played an integral part. Overall, however, the mood was upbeat; England had finally emerged from the dark post–World War II days. As Catherine Mason, who writes on the history of computer art in England, notes, “Cybernetic Serendipity [was] facilitated and inspired by a postwar spirit of optimism in the (positive) power of new technologies.” In her catalogue essay, Reichardt struck a more somber note: “Cybernetic Serendipity deals with possibilities rather than achievements, and in this sense it is prematurely optimistic.” Cybernetic Serendipity was one of several exhibitions that year which went against the grain by overtly celebrating the computer and computer art. An exhibition in Zagreb that August looked into the social and political implications of computers; not coincidentally, the organizers found it difficult to obtain funding.

Part of the show’s intent was to convince people that computers, which were new to the public at large, were not just not sinister, but cool. Reichardt noted that at first plotters—devices hooked up to computers for graphics—were used only for generating visual solutions to technical problems. Then engineers realized that they could also create pleasing images. “Thus people who would never have put pencil to paper, or brush to canvas, have started making images, both still and animated, which approximate and often look identical to what we call ‘art’ and put in public galleries.” The press had a field day on that one. The Sunday Telegraph wrote, “This exhibition . . . serves to show up . . . a desolation to be seen in art generally—that we haven’t the faintest idea these days what art is for or about.” The New Statesman commented, “The winking lights, the flickering television screens and the squawks from the music machines are signaling the end of abstract art; when machines can do it, it will not be worth doing.”

Catherine Mason points out a key aspect of Cybernetic Serendipity: “For computer scientists whose work was variously ignored, misunderstood or downright reviled, the importance of establishing a community of fellow practitioners and like-minded supporters was crucial to the continuance of their art.”

The Machine: As Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age

Around the same time that 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering and Cybernetic Serendipity were fueling an explosion of interest in technology, Pontus Hultén curated an exhibition entitled The Machine: As Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age at New York’s Museum of Modern Art from November 1968 to February 1969. The catalogue was dramatically bound in tin-can steel with an enamel-painted design of the MoMA building stamped on the cover.

This was a landmark exhibition on the history of the machine as depicted in art from the Renaissance to 1968. The works included prints, paintings, sculptural and mechanical works, and a few electromechanical pieces, together with an example of laser art and a couple of examples of computer graphics. The most radical work was Heart Beats Dust by the artist Jean Dupuy and the engineers Ralph Mosel and Hyman Harris: a throbbing sound, light, and color installation of red dust thrust into a cone of light.

Hultén stated, “This exhibition is not intended to provide an illustrated history of the machine throughout the ages but to present a selection of works that represent artists’ comments on aspects of the mechanical world.” The aim was to go beyond 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering. “Many artists today are working closely with engineers in collaborative efforts that may have significance far beyond that of merely producing new kinds of art for our delight,” Hultén went on. Technology was creating a brave new world, but it was important to bear in mind that “in planning for such a world, in helping to bring it into being, artists are more important than politicians, and even than technicians.”

Jack Burnham, art critic turned sometime art theorist, took this further in the exhibition Software which he curated at the Jewish Museum, New York, between September and November 1970. By now artists were working toward eliminating nonessential forms, aiming to grasp the essence of an object in a movement they called Minimalism. This fit neatly into conceptual art, where the concept takes precedence over the object’s material form. Art was becoming dematerialized.

As Sol Lewitt, one of the founders of conceptual and Minimalist art, wrote, “In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work. When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.”

Burnham saw a connection of this with another trend, the mixing of art and technology. 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering had explored how systems of electronics produced art; Cybernetic Serendipity studied the role played by computers in creative acts such as art, dance, and music; and The Machine: As Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age focused on the history of mechanical technology, from Leonardo’s drawings through to the 1966 E.A.T. exhibit.

Burnham sensed that the traditional media of art were being replaced by systems of electronics, sometimes guided by cybernetics. Systems analysis now stretched from policy-making to military planning all the way to Systems Art. Burnham decided to concentrate on the driver behind this: computer software, the ghost in the machine. To him, software was the essence of the new art. It was an information processing system, like the human mind. One art theorist, Edward Shanken, credits Burnham with seeing parallels between computer software and the “increasingly ‘dematerialized’ forms of experimental art.” Burnham’s insight was that it was no coincidence that conceptual art had emerged just at the moment of “intensive artistic experimentation with technology.” There was a clear parallelism there.

Software, sadly, was a failure. Several exhibits did not work, due—ironically—to software problems. There were disagreements with the board of trustees of the Jewish Museum, where it was housed, and it ran way over budget. Moreover, Burnham’s assumption that society was becoming increasingly centered on information and on a particular art form (conceptual art) was out of line with the times—which, in the 1970s, tended toward broader vistas such as Marxism, feminism, semiotics, and psychoanalysis. Postmodernism had arrived and immediately showed a distinct distaste for science.

On top of all these, the protests against the Vietnam War and the political climate that they engendered served to stymie any further collaboration between artists, scientists, and engineers. Students and other antiwar activists, including many artists, blamed science and technology for the development of lethal weapons such as napalm and Agent Orange. The scientific community itself was split over the issue. There was also economic recession, which meant that the funds for collaboration had pretty much dried up anyway, though the psychedelic drugs that were produced at the time no doubt played a part in inspiring later computer art.

As a result of these factors, there were few major collaborations during the 1970s and 1980s. Artists mainly worked alone on technological and scientific themes. However, interest in video art, among other experimental arts, persisted, challenging trends, particularly the growing commercialization of art as exemplified in Pop Art. Marshall McLuhan’s books, examining the changes in how we communicate with one another and presaging the Internet, also helped keep the idea of collaboration between artists and scientists alive.