In the early 1950s, electronic devices—such as televisions, washing machines, and telephones—were beginning to play a growing part in everyday life. Some artists, however, saw different possibilities in them. Rather than just being useful, perhaps they might produce an entirely new form of art, one suited to the forthcoming electronic age.

The pioneer was Ben F. Laposky, an American amateur mathematician and artist. He had never studied electronics but was often described as a natural. To him, the wavy images on the televisionlike screens of oscilloscopes—used to test electronic equipment by observing wave signals from constantly varying voltages—were reminiscent of the art of Duchamp, Malevich, and Mondrian.

Inputting two or more signals into an oscilloscope makes the wave forms pulsate, producing intriguing, ever-changing patterns. Using long exposures, Laposky photographed the images undulating on the screen, initially in black and white and later in color, making beautiful, curved, symmetrical designs. He called these Oscillons or Electronic Abstractions and in 1953 had an exhibition of them.

These were the first “computer graphics.” There were two notable points. The images were not man-made but machine-made, generated through automatic processes. The role of the artist was to work with the machine and select the most appealing images, rather than creating images himself. And there was a virtually infinite variety of possible forms.

Electronic art had begun.

The beginnings of computer art: A. Michael Noll

In the early 1960s, computers were in their infancy—large unwieldy machines used primarily for code-breaking and number-crunching—and they were so expensive that only universities, research laboratories, and large corporations could afford them. This meant that the only people who had access to them were computer scientists and mathematicians. Nevertheless, it was not long before lateral thinkers began to be curious about what else these clumsy machines might be capable of.

A. Michael Noll, an engineer at Bell Labs, was one of the first.

In those days, computers used a plotter: a brush or pen controlled by the computer that enabled it to draw. One day, when the summer interns at Bell were using the microfilm plotter to display their data, a programming error turned one student’s work into random graphical nonsense, which he jokingly called “computer art.” “I can still remember him running down the hallway with his ‘computer art,’ ” Noll writes. Inspired by the unintentional art, Noll decided to create it intentionally.

At Bell Labs, Noll had access to the latest computer technology—the IBM 7094—which was used to produce numerical solutions to complicated mathematical equations. This machine filled a huge room. Into it were fed equations and a means for solving them, in a programming language called FORTRAN, written on cards using punched holes at set positions, known as Hollerith cards. The operator would place a stack of cards in a hopper, push the on button, and the calculation would be up and running, with a whirring of tape drives in large cabinets and an array of lights flashing on and off. Such machines were essential to the Apollo space program, though today’s laptops easily outpower them, with disks and hard drives replacing tapes. To analyze the numerical solution—the computer’s output—engineers hooked it up to a plotter designed to make curves.

In the course of his work, Noll often did this with a microfilm plotter using 35mm film, which printed out the graphical results. After encountering the euphoric graduate student, he began to look at these curves differently. In August 1962, he wrote a technical memorandum describing them as “computer art.” The Bell Labs management, however, insisted that Noll call them “patterns,” because, they argued, “only the art world could determine what was ‘art.’ ”

Noll persisted. He was determined to produce something that everyone would concede was computer art. But how to do it apart from using patterns produced by solving equations? Random dots produced by a computer and joined up by lines would not be very interesting. But supposing he took points that appeared to be random but were not, then used a program to join them up?

So Noll wrote a program that produced dots distributed in a way prescribed by a mathematical equation called a Gaussian distribution which generates bell-like curves. He then connected the dots from bottom to top in a random way, producing a continuous zigzag. The result reminded him of Picasso’s Ma Jolie, which he had seen many times at the Museum of Modern Art. He called his creation Gaussian Quadratic.

For three years, Noll turned his attention from computer art to experimentation with three-dimensional animations, working with his colleague at Bell Labs, Ken Knowlton. Then, in 1965, Howard Wise, owner of a gallery on New York’s Upper West Side, invited Noll’s colleague, Béla Julesz, a thirty-seven-year-old Hungarian-born researcher in visual and auditory perception, to show his work there.

Wise, an art patron and a former dealer, had held exhibitions of Pop Art and was interested in dot images, such as in Roy Lichtenstein’s work. He had come across Julesz’s work in an article in Scientific American and was intrigued by the patterns Julesz created using pairs of random dots positioned not quite one above the other, so that when viewed with a stereoscope they produced an illusion of depth.

Julesz was reluctant to exhibit alone and asked Noll to join him. Noll was delighted, though, as he recalls humorously, “Béla always felt that his patterns were scientific with little artistic merit. I felt that my patterns were artistic with no scientific merit.” Nevertheless, the two young engineers were thrilled with this development. They were starting brand new artistic careers and at the very top, at the Howard Wise Gallery. They agreed to split the profits from their sales, though “in the end, not a single work was sold,” remembers Noll. Noll exhibited variations on Gaussian Quadratic, and he and Julesz also showed joint works of 3D stereoscopic images.

Noll and Julesz thought the exhibition would be a good demonstration of the creativity of Bell Labs, but the lab directors thought otherwise. This was the year before 9 Evenings took place, and they were still in cautious mode. They were reluctant to associate the lab with work that might be considered frivolous and generate negative publicity about the lab wasting money and resources. They put pressure on Wise to cancel the show. He responded that it had already been announced and threatened to take them to court. In the end Bell Labs backed down, but suggested to Julesz and Noll that they register the works under their own names and steer clear of journalists.

The copyright office at the Library of Congress balked at copyrighting a work as computer art, Noll recalls, claiming that something generated by a computer could not be art because a computer was merely a number-cruncher, incapable of doing anything creative. Noll replied that the computer’s output was created with programs written by a human being. The bureaucrats finally relented, and Gaussian Quadratic became the first copyrighted piece of computer art.

The exhibition was the “very first major public showing of digital computer art (certainly in the US),” Noll asserts. Stuart Preston wrote in the New York Times, “the wave of the future crashes significantly at the Howard Wise Gallery . . . freed from the tedium of technique . . . the artist will simply ‘create.’ ”

Computer art in Stuttgart

That same year, 1965, two German artists, Frieder Nake and Georg Nees, had exhibitions of computer art in Stuttgart. Nees’s exhibition was two months before Noll’s and could indeed lay claim to having been the first of its kind. Whereas Noll simply made art, Nake and Nees were driven by a philosophical agenda.

Nake and Nees were inspired by the German philosopher Max Bense, who had made the critical suggestion to Jasia Reichardt, “Look into computers.” Bense’s work involved exploring the possibility of using computers to pin down a scientific notion of aesthetics. Part of the basis of his theory was the Harvard mathematician George Birkhoff’s reduction of aesthetics to a mathematical formula: that beauty is in the inverse ratio of order to complexity, in other words, that the less complex an art object is, the more aesthetic it is. But what about intuition and subjectivity? Aesthetics was clearly more complex than this.

Bense combined Birkhoff’s ideas with developments in information theory, which studies the optimal conditions for transmitting a signal so that it arrives largely intact, and Noam Chomsky’s generative grammar, rules for generating language that are hardwired into the brain and therefore present from birth. How signals are transmitted through a background of random noise involves statistical analysis. Bense used statistics and uncertainty to devise a system free from the narrow mathematics of cause and effect, which had bedeviled Birkhoff’s theory. He concluded that creativity did not obey any rules of logic, and neither did aesthetics.

Bense called his framework “generative aesthetics.” He believed it could be applied to computers programmed with algorithms to produce almost random number sequences that generated aesthetic images which he called Generative Art.

Georg Nees, a doctoral student of Bense, put Bense’s ideas into practice. In his work Locken, the plotter’s pen traced out randomly generated arcs of circles. Nees intervened by turning the plotter off at the point where he intuitively felt that the image was complete and could be considered a work of art. Bense invited him to show his works at the Studiengalerie at Bense’s institute at the Technical University in Stuttgart. When the show opened, the public was outraged. “Some guests were nervous, some hostile, and some simply left at the thought of Nees’s drawings being considered art,” Nake writes of the opening. Bense’s response was to call Nees’s work “artificial art,” cleverly linking it with artificial intelligence and his own generative aesthetics.

Nake was a student of mathematics whose doctoral dissertation involved probability theory. While he was at Stuttgart, the university acquired a state-of-the-art plotter, a Zuse Z64 Graphomat. But there was no program for hooking it up to the computer, a Standard Elektronik Lorenz (ER65). The task fell to Nake. To test his programs he produced graphic representations, generating dots with pseudo (almost) random number generators and using his own intuition as to when to stop. Inspired by Bense, his aim was to write computer programs that would automatically generate drawings of an aesthetic quality with no other technical or economic purpose. Nake found the combination of intuition, creativity, and probability intriguing. He exhibited his works along with some of Nees’s at the Galerie Wendelin Niedlich in Stuttgart in November 1965.

The computer art produced by Nees and Nake at Stuttgart and by Noll at Bell Labs was of its time: linear, abstract, highly geometrical. “The drawings were not very exciting. But the principle was,” recalls Nake. Indeed, what the three were doing was quite revolutionary. Nake, Nees, and Noll are often referred to as the “three Ns” of computer art.

The computer versus Mondrian

“With hindsight, the digital computer has had a big impact on art, particularly in advertising, design, and animation. And a new breed of digital artist emerged,” writes Noll. With no philosophical axe to grind, Noll was freer. How about, he wondered, comparing art done by a computer, which at that time was made up of collections of lines, with art by an acknowledged master—for example, Mondrian, many of whose works also consisted of horizontal and vertical lines?

So Noll wrote a program that randomly connected randomly placed dots with horizontal and vertical bars. As in the works of Nees and Nake, the random dots were not in fact completely random. The randomness was determined by a mathematical algorithm for calculating sequences of numbers with no correlation between them. As the mathematician Robert R. Coveyou wrote, “The generation of random numbers is too important to be left to chance.”

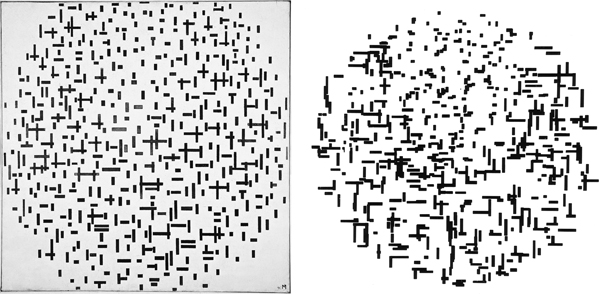

3.1: (left) Piet Mondrian, Composition with Lines, 1917. 3.2: (right) A. Michael Noll, Computer Composition With Lines, 1964.

Using a plotter, Noll produced a black and white image he called Computer Composition With Lines. Then he showed it to a hundred people at Bell Labs alongside a black and white photograph of Mondrian’s 1917 Composition with Lines. A mere 28 percent correctly identified the computer version, and 59 percent actually preferred it to the Mondrian. When asked, they explained that the computer image was neater, more varied, imaginative, soothing, and abstract. Non–technically-minded viewers, such as support staff, associated randomness with human creativity and incorrectly identified the computer-generated image as the Mondrian.

Here the puzzle of creativity enters, as it did for Bense, Nake, and Nees. Both pictures were actually conceived by humans but, in the case of Noll’s, with the computer as an interface between the human programmer-artist and the plotter. Noll concluded that “artistic merit is not . . . something that can be determined by jury.”

40,000 Years of Modern Art

Back in 1851, the hugely successful Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in London promoted both art and design. It was the brainchild of Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s consort, who had long advocated the coming together of “Raw Materials,” “Machinery,” “Manufactures,” and “Sculptures.” But it did little to counter the schism in the British art establishment between fine arts and crafts, which practitioners argued had nothing to do with each other. Crafts were generally relegated to a lower status than fine arts. And after World War II, “technology” was added to “crafts.”

Then, in 1946, just after the end of World War II, the poet, anarchist, art critic, and historian Herbert Read founded the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, with the specific aim of providing a space for avant-garde art and debate. The first exhibition was Forty Years of Modern Art, the second, in 1948, was outrageously entitled 40,000 Years of Modern Art. It was a showstopper. Curated by Read and Roland Penrose, it included Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, on loan from the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In the early 1950s, the younger artists, scientists, and designers at the ICA formed the Independent Group. The historian Catherine Mason writes, “The Group’s avant-garde artistic practices, which advocated that the artist take advantage of the new technologies, contradicted the perception of a complete gulf between the sciences and the humanities in Britain.” Artists and scientists were finally beginning to come together.

Beauty in nature: Richard Hamilton

The artist Richard Hamilton, an active member of the ICA, and his scientific collaborator Kathleen Lonsdale, an eminent crystallographer at University College London, were the driving force behind the exhibition Growth and Form at the ICA in 1951. It was an attempt to bring the arts and sciences together and focused on aspects of growth, form, and structure in atoms, crystals, animals, plants, and stars. Hamilton created an environment with enlarged photos taken through microscopes and films showing the growth of crystals and sea urchins, literally engulfing viewers. Lonsdale believed that symmetries in crystals were aesthetic in an artistic as well as in a scientific sense. She was much influenced by Charles J. Biederman’s Art as the Evolution of Visual Knowledge, in which he proposed that artists should look to science for themes rather than to the world of the emotions.

For his part, Hamilton was inspired by D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s On Growth and Form, which explains the title of the exhibition. Thompson was a scientist of some note and also an accomplished classicist. In his beautifully written book, he describes how forms in nature conform to mathematics. These were the words that caught Hamilton’s eye: “The world is as it is, because it must follow certain mathematical principles.” If artists wanted to look for beauty in nature, they would have to turn to science.

Inspired by the exhibition, a simultaneous gathering of major artists and scientists was held, entitled Aspects of Form: A Symposium on Form in Nature and Art. Among the speakers were Rudolf Arnheim, Ernst Gombrich, and Konrad Lorenz. The Scottish financier, industrial engineer, physicist, and intellectual gadfly Lancelot Law Whyte made the comment that “There is something to gain . . . from examining the ideas of colleagues in neighboring fields.” Today such a thought would seem innocuous enough. But at the time it was downright revolutionary.

Hamilton was one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century and a close friend of many avant-garde painters, including Marcel Duchamp, who often attended discussions at the ICA. His 1956 work Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? is a comic book–like collage featuring a sitting room with an automobile advertisement on the wall, a woman with pneumatic breasts, expensive furniture, and a body builder holding a lollipop with the word “POP” on it. “Catch up with America and its technology” is written all over it. The work became iconic. Thus was born Pop Art, the movement that displaced American Abstract Expressionism and extolled technology as well as art. Hamilton gave his own definition of Pop Art as “Popular (designed for a mass audience), Transient (short-term-solution), Expendable (easily forgotten), Low-cost, Mass-produced, Young (aimed at youth), Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous, Big Business.”

Abstract art: Victor Pasmore

As early as 1947, Richard Hamilton and Victor Pasmore were teaching at the Central School of Art and Design in London following a curriculum styled after the Bauhaus School, which was founded by the German architect Walter Gropius in Weimar in 1919 and lasted twenty years until it was closed down by the Nazis. In their Basic Design Course, the Bauhaus members sought to blur distinctions between fine art and design, which they took to include technology.

Pasmore had begun his painting career as an impressionist in the fine art tradition. Then, inspired by Klee and Kandinsky, he shocked the art establishment by turning abstract. “While [abstraction] was fine in design, it was in Fine Art that it caused an uproar,” he wrote. Built up of lines, with a minimalist geometry, his subsequent work had a specifically scientific and technological bent. At the same time, American Abstract Expressionism was bursting onto the European scene, exciting young artists. It too was anathema to the “fine arts.”

If he was to extend his own version of the Basic Course to include abstract art, Pasmore would have to go elsewhere. His work was well known and he had no trouble obtaining a position at King’s College in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1953. A year later, Hamilton joined him. Soon other “outlying” art schools started taking an interest in what Hamilton and Pasmore were doing. First Sunderland School of Art, and then Leeds College of Art instituted Basic Courses. By 1960, the Basic Course had become a model for first-year art studies as well as for a radical overhaul of art teaching.

A radical new outlook: Roy Ascott

I first came across Roy Ascott at a symposium at the University of Plymouth, where he is a professor. His lecture was more a performance, presented with feet on desk, covering everything from his journey through art theory and art practice, to Zen Buddhism and consciousness studies. Short and stocky with an air of great confidence, he exudes a genuine and disarming friendliness.

Ascott is and always has been a maverick. At King’s College, Newcastle, he learned painting from those two radicals who had shaken up the London scene, Hamilton and Pasmore. Jokingly he recalls having been on the verge of psychosis after studying painting under two such different artists, one Pop, the other geometrical, and who offered totally opposing viewpoints of the world in which we live.

This sparked an interest in the French artist Paul Cézanne, who exploded a single perspective point into several, drawing out from the flux of experiences that flood the eye, creating new ways of visualizing a scene. Ascott concluded that the viewer had to play an active part in a work of art; it should be a joint project. “It can be argued that the aesthetic of process and emergence in computer-mediated art starts here,” with Cézanne, he writes. The key notion was process, of interaction between artist and viewer, forming a system.

This concept of process and system took further root when Ascott visited the Paris studio of Nicolas Schöffer, the father of cybernetic art, in 1957. Schöffer, he says, was the “kinetic art king; Schöffer did it big and shiny.” For Schöffer, “Cybernetics was everywhere and could even lead to a new civilization.” Ascott was impressed with Schöffer’s dedication not only to bringing cybernetics into art but to shaping a new worldview as well.

With the core idea of cybernetics in mind—interactions within a system—he produced a series of paintings in which paint was applied in a random way to glass panels that the viewer could slide back and forth, creating new works every time. In this style of art, “gestural painting” or “action painting,” the system was the glass panels plus the viewer. He called them Change Paintings.

Pasmore wanted to take the Basic Design Course back to London and chose Ascott, his star student, to do so. In 1961, on Pasmore’s weighty recommendation, Ascott became head of Foundational Studies at the Ealing College of Art.

3.3: Roy Ascott, Change-Painting, 1960.

Just before leaving King’s College, Ascott had come across books on cybernetics by Norbert Wiener and others. For him it was a “Eureka experience—a visionary flash of insight in which I saw something whole, complete, and entire.” The mathematics was beyond him, but he happened to know someone who could help him: Gordon Pask. A distinguished researcher in cybernetics and psychology, Pask owned Systems Research Ltd in Surrey, one of whose specialties was adaptive teaching machines, designed to construct knowledge through interactions between humans and machines.

After one of his exhibitions, Ascott asked Pask to explain cybernetics to him. Back at Ascott’s studio, Pask gave him the tutorial of his life, which lasted until 2 am and convinced him that “ ‘control and communication in animal and machine’ is a proper study for the artist.”

At Ealing, Ascott instituted the now famous Ground Course, a radical experiment in art education. Inspired by systems thinking from cybernetics, the aim was to give students a personal involvement in their art, surroundings, and social contexts. The Ground Course was a bit like an art boot camp. One way in which Ascott put students in touch with themselves was to lock a group in a pitch-dark lecture hall and subject them to intense flashes of light. Then they were released into another room where they stumbled over a floor covered in marbles, startling passersby.

Ascott firmly believed in blurring the distinctions between art, science, and technology, and often invited scientists and technologists to lecture. Pask, the cybernetic maestro, gave a lecture on the German-born artist and political activist Gustav Metzger and his auto-destructive art. Metzger’s demonstrations were a protest against the use of technology, especially computers, by the military. Yet there was a positive aspect too, as he wrote in his Third Manifesto: “Auto-destructive art and auto-creative art aim at the integration of art with the advances of science and technology.”

In 1962, Metzger himself gave a lecture at Ealing. One of the students who attended was a young man named Pete Townshend. He was greatly inspired by Metzger and incorporated his attitudes into his own, now legendary, guitar-smashing performances with The Who.

Among the staff at Ealing were the Cohen brothers, Bernard and Harold. Bernard was already a famous “young Brit” artist, producing paintings that were highly geometrical and abstract. Harold was more influenced by cybernetics; in a few years he would become a computer artist, exploring whether computers could produce art indistinguishable from art made by people.

Ascott’s methods of teaching, as well as his art, were too revolutionary for the majority of the staff at Ealing. In 1964, three years after he’d arrived, he moved to Ipswich Civic College, another institution at which the London art world looked down its nose. Among his students was Brian Eno, soon to be massively famous for his experimental electronic music. Eno had enrolled at Ipswich because he couldn’t get in anywhere else. He was excited to find that instead of painting and sculpting, this art school was interested in concepts. It was all about “cultures being leveled. We could see that [art and science] were not different places, we felt that we could understand something about the sciences and re-digest them and do our own experiments with them.”

Systems Art: Cornock and Edmonds

In 1966, the new Labor government responded to the increasing demand for further education by merging local technical and regional colleges and forming polytechnics. This meant that expensive equipment like computers could be concentrated in a few cross-disciplinary centers, though traditional artists loathed rubbing shoulders with engineers. A few years later, the eminent writer and painter Patrick Heron published a long article in the Guardian complaining of the “Murder of the Art Schools.”

The polytechnics may have threatened the traditional art world but they were of immense importance in the rise of computer art. They were playgrounds where artists could use equipment not originally intended for artistic purposes—and to find out how to use it they had to seek out engineers and scientists. One such artist was Ernest Edmonds, who had been impressed by the ICA’s Cybernetic Serendipity in 1968.

Inspired by Cézanne and Matisse, Edmonds had wanted to be an artist. He opted, however, to study mathematics and logic, and completed a PhD in mathematical logic in 1969 at the University of Nottingham, while he was on the staff at Leicester Polytechnic. Mathematics came easily to him, which gave him free time to pursue his interest in art.

Initially Edmonds was interested in El Lissitzky’s Constructivist art and in concrete poetry, in those days written with a teletype machine or drawn with plotters. He had some questions about spray-painting techniques and dropped into Leicester Art College, at Leicester Polytechnic, where he encountered Stroud Cornock, a sculptor who was adept at computers. Cornock introduced him to Systems Art, the concept of participation and interaction in art combined with rules for proceeding, based to some extent on feedback from cybernetics. The two began projects based on the theme that “creativity is not totally in the hands of the artist.” The basis of this approach was the rule-governed system: the artist establishes rules and creates a work of art within set boundaries, in the same way that music, language, and science are all governed by rules. In music, there are a finite number of notes and keys, and rules for combining them. Yet composers can create an infinite number of wonderful compositions.

Edmonds realized that what he had found so appealing in Cézanne and Matisse’s work was their conciseness and the “clear emphasis on composition, the power of composition and what was underlying it.” He analyzed the structures in Mondrian’s work and concluded that it was more “non-constrained than it appeared to be.” In other words, although Mondrian’s paintings seemed rigidly geometrical, as in his Composition with Lines, they were actually quite loose in structure.

With the rather basic computers available in the 1970s, Cornock and Edmonds constructed algorithms—rules for solving problems—and looked into how these rules could aid creativity. Perhaps, they suggested, “it may no longer be necessary to assume that an ‘artist’ is a specialist in art.” As 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering had shown, the “concept of art can survive artists as we know them when their control of the situation is reduced or when they are submerged in collaboration with engineers.” In other words, the concept of art will change as artists collaborate with engineers.

Son of SAM

Edward Ihnatowicz, the inventor of Sound Activated Mobile, the flowerlike robotic creation that leaned forward and listened to people’s conversations at Cybernetic Serendipity, wrote, “We live in an industrialized, technological, and commercial world and if art is to have any relevance to it, it cannot hide in the romantic, artist-in-the-garret cocoon but must be prepared to come out and join the fray.” Ihnatowicz was one of the first artists to incorporate a computer in a large-scale production. For this the contacts he made in the mechanical engineering department at University College London, when he built SAM, were crucial. He realized he needed to learn more about computers.

Ihnatowicz was interested in doing more than just making interactive machines. Suppose it were possible to make an intelligent machine? The only way such a machine could be created would be by programming it to interact with its environment, building its intelligence from the ground up, the opposite of the “top down” approach of artificial intelligence (AI), where mental processes are taken as given and written in code. To back up this approach, he referred to the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget’s theory that children develop intelligence by interacting with their day-to-day world.

The result was the colossal Senster. Fifteen feet long and eight feet tall, it was a horned beast made of welded steel and looked like a cross between a giraffe and an electricity pylon or a gigantic lobster’s claw. Unlike SAM, it responded to movement as well as sound. It was the first work of robotic sculpture to be controlled by a digital computer and was funded by Philips, the Dutch electronics giant. Ihnatowicz built it at University College London (UCL) and exhibited it between 1970 and 1974 at Evoluon, an electronics exhibition founded by Philips in Eindhoven, the birthplace of Frits Philips, the owner-founder.

James Gardner, the design engineer who created Evoluon, wrote:

Our aim is to get people (the press) to understand the Senster and not just treat it as “a gimmick”. Ihnatowicz is an artist (sculptor) who is interested in science (biology, electronics, stress engineering). The Senster combines art and science. The art bit should not be forgotten as it cannot be categorized but is far more complex than exact science is(!).

Senster went way beyond what Alexander Calder had accomplished with his mobiles—which, even when powered by engines, merely repeated movements. It went beyond Tinguely, whose machines were aimless, and even beyond Schöffer, whose sculptures were not computer-operated. Ihnatowicz, clearly something of a joker, liked to describe Senster in human terms: “In the quiet of the early morning the machine would be found with its head down, listening to the faint noise of its own hydraulic pumps. Then, if a girl walked by, the head would follow her, looking at her legs.”

The computer that paints: Harold Cohen

The Slade School of Fine Art was established in 1871, and was modeled on art schools in Europe which treated art as a means of studying nature. A hundred years later, in 1972, under the visionary leadership of Slade professor William Coldstream, the forward-thinking artist Malcolm Hughes set up a center for computer artists at the Slade called the Experimental and Computing Department, or EXP. Hughes’s assistant, Chris Briscoe, was in charge of the day-to-day running of EXP. Trained as an architect, Briscoe was brilliant at electronics. He taught artists the computer language FORTRAN, built circuits, and customized plotters as well as setting up the department’s Data General mainframe.

Hughes invited lecturers such as Ihnatowicz, then a research assistant in the mechanical engineering department at UCL, and Harold Cohen, then at Stanford University in California, who described the latest version of his computer program AARON, which generated paintings. The students were thrilled to be taught by such accomplished and innovative artists. One, Paul Brown, declares, “For me, Ihnatowicz and Cohen represent the first two great masters of the computational arts.”

Born in Britain, Harold Cohen was an acclaimed Systems artist whose work was a highlight at the Venice Biennale of 1966. He emigrated to the US in 1968 and joined the staff at the University of California at San Diego.

There “I met my first computer,” Cohen recalls. “I was simply grabbed by the experience of programming; the extraordinary excitement of finding my brain working in an entirely new way. I had the feeling that there must surely be more to computing than came through in [Cybernetic Serendipity].” Right from the start, his aim in working with computers differed from that of just about every other artist, including Edmonds. He was interested in artificial intelligence, in whether machines could learn from a set of input rules such as those that governed drawing and painting. Three years later, as a guest at Stanford University’s Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, he began putting together AARON. He has continued to elaborate on it.

AARON is a highly complex series of programs based on two sorts of knowledge, declarative and procedural, declarative being knowledge of facts and things—arms, legs, bodies, shapes, and colors—and procedural being the knowledge of how to use them. A phone number is declarative knowledge, knowing how to use it is procedural knowledge. Cohen’s rules are procedural. He has taught AARON to produce paintings in endless permutations and combinations of colors, styles, and topics from figurative to abstract, though he has yet to reveal the specific AARON algorithm. AARON’s paintings, such as Merging Systems, are pleasant and colorful though the limitation is that AARON can only produce work using whatever material Cohen inserts. Nevertheless they have been widely distributed. In effect, AARON is an artist in itself.

3.4: Harold Cohen, Merging Systems, 2013.

Computerized special effects: Paul Brown

The late 1970s and early 1980s were a fallow time for computer art. Besides dwindling government funds due to the anti–Vietnam War movements, there was the rise of postmodernism, which favored forms less linear and rational than those produced by computers. In Britain there were also cutbacks in government spending on education in the Thatcher era, particularly on work that had no immediate practical applications.

At the Slade, a further problem was resistance among the teaching staff to the use of computers for anything outside of science and technology. In 1981, the Slade’s experimental department, EXP, closed its doors, though Chris Briscoe, the computer whiz kid who had run EXP, stayed on. In partnership with the Slade, he and his former student, Paul Brown, founded Digital Pictures, the first company in England to focus on computerized special effects. They were quickly snowed under with work.

Before his time at the Slade, Brown’s life had taken an unconventional path. He studied at Manchester College of Art but hated the way in which students were limited to painting, printmaking, or sculpture. After he left, he became the artistic director of a light show called Nova Express which worked with legendary bands such as Pink Floyd and The Who. To start off with, light shows accompanied the music and stopped when the musicians left the stage. But why not fill the break with a different sort of light show, something more than a play of lights? His idea was to press water and oil between thin glass plates, creating random patterns, then illuminate them from below and project them. The squashing of oil and water by the glass plates, in addition to extreme heat from the lights, causing turbulence, made endlessly changing patterns. “The audience was enraptured by the oil and water light shows.” Brown himself was impressed with the “amplification of minute turbulent events and how art could be made out of random physical events.”

3.5: Paul Brown, Swimming Pool, 1997.

Brown also produced a video, Mandala, which was shown at The Video Show at the Serpentine Gallery in London in 1974, the first retrospective of video art in the UK. But he wanted to go further, and computers offered a promising route. Then he heard about EXP at the Slade, discovered Systems Art, and set to work to take it “into the computational domain.” He continued the theme of shapes existing in water, using algorithms, as in 1997’s Swimming Pool.

Media art as fine art: Susan Collins

Susan Collins, director of the Slade and professor of fine art, brought computer art back to the Slade fourteen years after EXP closed its doors in 1981.

Collins discovered computers during a visit to New York, where she was shown a new Mac computer with a primitive drawing program. She was greatly impressed that one could draw and save as many versions as one wished. “Now I could take enormous risks.”

Back in London, in 1988, there was still considerable distrust of computers. It was difficult even to get access to one. When Collins started making computer art, she found that no one really looked at her work, just at the computer itself. Only in the 1990s did the Slade begin to pay attention again to computer art, and in 1995 Collins was asked to be the computer tutor.

Collins did not want to set up merely a “computer facility for fine art.” She wanted media art to be integrated with fine art. “I had such a clear vision of what it should be like to have media art embedded in the fine art environment,” she recalls. She was convinced that electronic media should be studio- rather than technology-driven.

3.6: Susan Collins, Seascape, Folkestone, 25th October 2008 at 11:41 am.

Collins’s work Seascape demonstrates her conception of “art and technology.” She positioned five webcams at various vantage points along the south coast of England, all framing the horizon and collecting, transmitting, and archiving images slowly, pixel by pixel. The images were continuously updated in real time, to create a fluctuating image on the screen. When printed out, they look like paintings of seascapes. It is only on close inspection that the viewer can make out the pixels.

Making art move: back to Ernest Edmonds

In 1970, Ernest Edmonds was working on Systems Art at Leicester Polytechnic and pondering what it meant for an artist to interact with a computer. He was sure the computer would never replace the artist. Rather, he saw it as a control system in which the artist’s job was to figure out how it worked. The “computer as a control system,” he says, “set up a landscape where participants could operate. The artist’s job was to define the space of opportunity—a decision space.” But at the time he could not pursue these ideas because of the limitations of the available computers and computer software (FORTRAN).

Edmonds’s background in mathematics, and his interest in cognitive science, led him to consider “control issues as conceptual,” and to ask questions such as, Where does software stand? What is the role of software now?

If software was art, it was closest to poetry. After all, “a poem is something more than words on a piece of paper.” He concluded that the “essence of software art is not materiality.” Perhaps software was like the mind controlling the hardware or brain.

Then Edmonds heard a story about a meeting between the kinetic artist Alexander Calder, famous for his mobiles, and Piet Mondrian. “Calder walked into Mondrian’s studio, looked at the highly geometrical works he was producing and asked him, ‘Can we see them move?’ ” Inspired by this, Edmonds, too, wanted to find a way to make art move. He started working out computer programs that could generate a time-based art, based on algorithms that arranged colors over time intervals; they contained rules for time, as in music, as well as rules for the spatial arrangements of form (often squares). The result was a succession of abstract artworks based on simple structures. It was computer animation in real time instead of in frames—a step forward in this art form. Eventually, Edmonds found a way to project directly from the computer. To him, the work he created was a dialogue between the computer and the artist.

Edmonds is currently exploring the use of sensors such as cameras, microphones, and telephones to trigger rules, thereby adding another layer to the system of artist, computer, audience (see Insert). He is also rethinking cybernetics and systems theory, seeking ways to extract form from chaotic situations. He tells his students, “If you want to paint with oil paint, you need to understand oil paint. If you paint with software, you really have to understand software.”

Getting connected: Roy Ascott again

“Man, you’re a real artist,” a colleague at San Francisco State College said to Roy Ascott after Ascott punched someone who had made derisive comments about his art at a faculty meeting.

Ascott, the maverick who revolutionized art teaching, founded the Ground Course at Ealing, and inspired Pete Townshend and Brian Eno, held a succession of posts in the United States and the UK and was sacked from most of them. He now teaches at the University of Plymouth.

Since 1980, he has been exploring telematics, the bringing together of telecommunications with informatics, i.e., information technology, though he interprets this more widely, as a “technology of thought transfer” of information through cyberspace. He felt it was important to fit art into this scheme to allay fears of a dystopian world governed by technology run amok, which was what some predicted after two highly mechanized world wars and the onset of nuclear warfare. In particular, he wanted to find a way to draw the viewer into works of computer art, which all too often seemed cold and mechanical. Ever since the 1960s, he had been convinced that cybernetics, with its feedback loops, offered a way to bring together viewer, artist, and machine in a “telematic embrace,” in which there would be “love” among them. But for this to occur, it would have to be at the level of consciousness.

At Ars Electronica in 1982, the Canadian artist Robert Adrian anticipated Ascott. In his interactive piece The World in Twenty-Four Hours, Adrian connected artists in fifteen cities around the world by telex and telephone, enabling them to exchange ideas which were fed into a computer. The technology was primitive and the results disappointing, but this was not the point. As everyone realized, the exercise showed that the “real power of the computer was connective, rather than a device or system just to make better pictures,” as Gerfried Stocker, the present artistic director of Ars Electronica, puts it.

Ascott, meanwhile, expanded telematics to include consciousness and called it “technoetics,” encompassing art, technology, and the mind. He coined the term in 1994 while teaching at the University of Wales, in Cardiff, where he founded the Planetary Collegium for the study of art, science, technology, and consciousness, the idea being that the four disciplines should work together to enhance creativity.

Ascott states that “consciousness is not generated, it preexists.” It cannot be reduced to matter and therefore is not open to the laws of physics and chemistry as we know them today. His point of view includes a heavy dose of speculation and nonstandard interpretations of quantum physics (regarding the effect of an observer’s consciousness on measurements), topped up with shamanism, which he experienced firsthand while living with a Brazilian tribe in the Upper Amazon.

Ascott’s first major retrospective took place in London in 2011. It was entitled Roy Ascott: The Syncretic Sense, in which “syncretic” refers to bringing together disciplines that seem to have no connection. His Change Paintings were on show, as well as other interactive works. There were few computers. The key element was the use of feedback loops in promoting syncretism.