Unlike visual art, sound art surrounds us and has the capacity to create an atmosphere—a world. Sound art ranges widely. A very early example is Yoko Ono’s Cough Piece, “scored” in 1961 and recorded in 1963, consisting of thirty minutes of coughing varying in rhythm, intensity, and volume, complete with background sounds. At the other end of the spectrum is today’s computer-augmented music.

Most people agree that sound art probably began in earnest with John Cage, many of whose scores consist of random sounds from random sources, such as his performance at the now legendary 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering in New York in 1966, not to mention his groundbreaking 4’33”—4 minutes, 33 seconds of total silence, carefully divided into three movements of unequal length, at the end of each of which the pianist closes the piano lid and opens it again.

At Supersonix: Celebrate the Art and Science of Sound, an event in London in 2012, the sound artists’ “conference papers” are their performances. “Sound art has the shortest tradition,” says Angus Carlyle, a London-based composer, speaking into a microphone linked to a computer. There is a lengthy silence while translation software translates his words into French. Solemnly Carlyle listens to the French translation through earphones, then retranslates it word for word back into English. That’s it. Aura Satz, another London-based sound artist, takes the stage. “I will be deliberately slow,” she says, and indeed she is. She reads each sentence of her paper extremely slowly. Once again, silence is a key element.

In the question and answer session, the panelists insist on the connection between art practice and art research—that art is research. The chair, Salomé Voegelin, a London-based sound artist and writer, emphasizes the importance of the “independence of the sound image from the visual image,” of engaging separately with sound as distinct from visual art.

The speakers banter around the term “aesthetics” with no clear definition. This is surprising, because a key issue in sound art is how to rethink the visual aesthetic toward evolving an aesthetics of sound, how to move from seeing to hearing. Sound performances sometimes involve a sensitive table on which performers place objects and move them around to make sounds, often accompanied by computer-generated images. Sometimes performers play musical instruments along with electronic devices. Sometimes sound can even be sculpted by otherworldly objects. The sound artist Katie Paterson translated the score of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” into Morse code, then transmitted it onto the surface of the moon. When it was reflected back to earth, parts had been lost on the moon’s rough surface, absorbed in its shadows and craters. She called this the “moon-altered” version and retranslated it into a new score with the gaps represented by intervals. In her performance the new score is played by a self-playing grand piano.

Sculpting sound: Bernhard Leitner

“What does it mean if you really move sound in space?” asks Bernhard Leitner, a pioneer of sound art.

Leitner is one of those people who looks much the same as he must have done in the 1960s. His shoulder-length white hair, tucked behind his ears, enhances the look. For me, meeting him is a high point of Supersonix.

Born in Austria in 1938, Leitner was, to begin with, interested in classical music. In the late 1950s and early 1960s he studied architecture in Vienna, where he was swept up in the New Music by composers who were turning the music world upside down: Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luigi Nono, Mauricio Kagel. To him, this New Music seemed to open up space. From Vienna, Leitner traveled to Paris, then attended the cutting-edge International Summer Courses for New Music in Darmstadt, Germany, in which tonal writing was virtually banned. France and Germany were the European poles of the New Music.

What appealed to Leitner was the way Stockhausen manipulated sound. His Piano Pieces (1952) epitomized the “reigning aesthetic of pulverization: sounds ricochet from the top to the bottom of the piano, as if the instrument were a pinball machine,” as the music critic Alex Ross puts it. Then Stockhausen moved into electronic music, which further expanded the range of sound available to composers.

Leitner was intrigued by the notation for the New Music, the way the complex chord rotations were expressed graphically. Seeing this with the eye of an architect, he was drawn to their spatial characteristics.

Leitner pays homage to Cage, whom he sees as breaking down the concept of music by widening it, much as Duchamp did with art. The French-born composer Edgard Varèse, in his opinion, was even more important than Cage, in that he “re-envisioned sound itself,” constructing installations for experiencing how sound moves through space. Varèse is celebrated as the father of electronic music. In addition, the Greek musician and music theorist Iannis Xenakis appealed to Leitner’s architectural side, in that he attempted to sculpt sound. Xenakis made important contributions to the New Music by injecting into it concepts from mathematics, such as theories of randomness.

Finally, there was modern dance, which Leitner had always loved.

In 1968, Leitner was mulling over these three strands—architecture, which dealt with space, music, which dealt with time, and dance, which concerned movement in space and time—when he took a flight to the US. He had stopped thinking of this problem. “This subconscious detachment or liberation,” he recalls, was the key. The passionate, intense desire to solve a problem keeps it alive in the unconscious. Then it came to him—“a spark-like confluence of thought, leading to an idea whose content was a kind of manifesto: Yes, why not use sound as building material?”

“I could not have developed my work in Vienna because it was too close, everyone on top of everyone else,” Leitner recalls. “I needed a city that is really pulsating”—a city where he could be anonymous but that was also inspiring. New York was the answer. He settled into the Lower East Side, “where most things happened.” Among those he met was Billy Klüver, and there was plenty of intellectual stimulation from hanging around with writers and artists connected with the magazine Artforum. He soon found work as an urban designer in the city planning office, and in 1972 New York University appointed him head of the study program in urban design. This gave him the financial security to afford spacious studios where he could pursue his “theoretical investigations” toward the idea which he had come upon on the plane. He needed a language to deal with “sound as architectural material.” In 1968, “no one talked about sound.”

Art and architecture are spatial, while music is temporal. The different disciplines had to be put together into a metaphorical four-dimensional language which would not be static, as it is in architecture. Such a language existed already for dance, and there were also the graphic representations of the New Music.

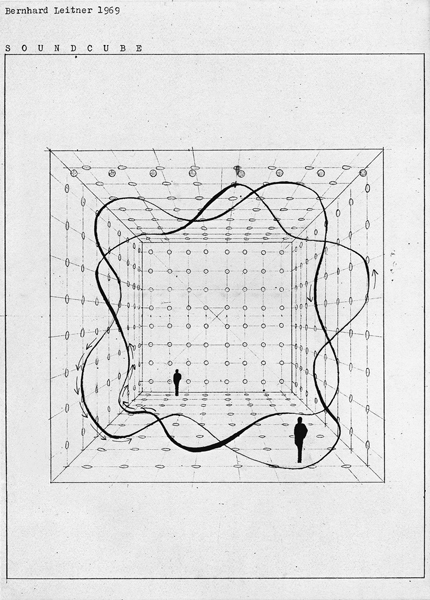

The new language Leitner came up with was a representation of sound with sound lines that crisscrossed, bunched up where sound was more intense, and changed direction, whose characteristics could be altered by using different materials, taking into account his belief that sound is material and can be sculpted. In this way he could plan sound spaces which could support different motions, such as linear or spiraling or in the shape of an arch or a pendulum.

Between 1968 and 1970 Leitner produced a series of intricate architectural-style sketches—meticulous drawings on graph paper—for placing speakers in relation to an observer. Now he was finally ready to start on his “empirical studies.”

In these arrangements of speakers he found a “corporeality of listening. Ears are fine, but we have sensory instruments all over us. On our skin there are ‘acoustic cells.’ ” He realized that we hear differently depending on our constitutions—the amount of weight we carry affects the sound waves reaching our skeleton. “I hear with my knee better than with my calf.” The soles of our feet are especially acoustically sensitive. In fact, we are made up of sound spaces, yet know little about these interior spaces.

8.1: Bernhard Leitner, SOUND CUBE. Two sound spaces, in countermotion, intertwined, 1969.

In the early days of his empirical work, in 1971, Leitner had twenty speakers controlled by a voltage-changing device called a potentiometer, which altered the volume on each speaker. Two years later, he was using over forty speakers controlled by an electronic device driven by punched tape. The output came not from musical compositions but from sound recordings taken from the environment. His installations were huge, up to 130 by 130 feet. They filled his studio. Nowadays he uses computers to control the speakers.

In recent years Leitner has been working with haptic sound: sound you can touch. Using parabolic mirrors he can “bundle up” sound and bounce it off walls. Visitors can hear as well as sense the sounds moving up and down the walls, and even reach out and try to touch them. The visual part of the artwork is the speakers and the actual art is the sound. It’s an extraordinary, immersive experience.

In 1975, Leitner designed the sound chair, a reclining chair with six speakers distributed across the back. The speakers are hooked up to make the sound move back and forth and up and down the body. “In the sound chair, sound doesn’t leave the body. Sound spaces can go through the body.” Leitner recalls that at an exhibition at MoMA’s PS1 gallery in New York in 1979, Cage lay back in the chair and expressed amazement at feeling the sound moving over and within his body.

In the 1980s, doctors at the Bonn University Clinic tested the sound chair. They found that after sitting in it for twenty minutes, many preoperative patients were more relaxed, describing the experience as “a kind of holistic thinking.” Perhaps they meant it was a kind of meditation. Some doctors noticed that patients who had received the sound chair therapy had a faster recovery rate than those who had not. “It was a medical research project that developed out of an artistic research project,” Leitner says. It is indeed a very interesting example of science benefiting from art, or, as Leitner puts it, “medical research following an empirical aesthetic approach.”

Leitner interprets aesthetics as a minimalist concept characterized by clean lines with clear-cut patterns, as in his meticulous drawings which set down sound lines and speaker positions. As for the intuitive side of aesthetics, it is the experience gained from experiment. For Leitner art is research.

He sees a difference between his own research and that of scientists, for whom the parameters are more clearly defined. In his case, he says, the unconscious plays a larger role. Constructing diagrams for speaker configurations requires a great deal of rational input—the measurements of the room, the electrical characteristics of the speakers. But irrationality chips in to the finished artwork as he feels out the best configuration of sound lines to produce a harmonious response in the body and the senses.

He does not consider that irrationality plays a large part in scientific discovery—an opinion with which I disagree. But we agree on the intriguing distinction in German between “to invent”—erfinden—and “to discover”—finden. People invent automobiles but they discover scientific theories, in that they are plucked from the cosmos.

In 1981 Leitner left New York for Berlin. He is now professor of fine art at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. For forty years, he says, galleries took no interest in his work. He did, however, exhibit in museum shows and at international festivals like Documenta 7 in Kassel, the Venice Biennale, and Ars Electronica in Linz. Sometimes museums bought pieces. Fortunately, Leitner had a steady income as a university professor.

“The art market,” he says, “goes through galleries which establish a certain kind of aesthetic evaluation.” For many years, sound art was not shown by galleries because of the widespread bias against art associated with technology. Recently galleries have begun to take an interest in his work, though, he says, “White Cube and sound art just don’t work. Collectors are not interested in something you can’t put on the wall.” One problem that galleries or buyers anticipate with art that involves science is durability. If it breaks down, can you call the artist in to fix it? Leitner points out that there have been enormous advances in technology, from two-channel tapes to CDs to chips in which the only moving parts are electrons. This means that durability is no longer a problem. People buy sound art to live with it. Leitner recently sold a large piece to a friend who put it in his courtyard. It’s not only eye-catching but a conversation piece.

Beyond music: Sam Auinger

Rather than creating sounds, Sam Auinger harvests them.

In 1991, Auinger was in Trajan’s Forum in Rome with the American composer and sound artist Bruce Odland. The two often work together, signing their works O+A. As always, they were alive to their environment, listening to the sounds. Trajan’s Forum was a hideous cacophony of cars, buses, horns, and sirens from passing traffic. The shape of the forum actually amplified these sounds, resulting in cognitive dissonance between what the two saw and what they heard. On an upper floor of the market they found piles of amphorae, large ceramic vases which were used as shipping containers in ancient Rome. Applying their adage—“We, O+A, listen to everything. Everything.”—they lowered a microphone into an amphora and listened to the results through headphones, expecting to hear not very much. In fact it was a “hallelujah” moment. They had struck gold. What they found would affect their research for years to come.

Instead of the barrage of street noise, the sound they heard had been mysteriously processed so that it was “jaw-droppingly profound, deeply mystifying, and very real.” Actually they had rediscovered a basic effect in physics. The amphora acted like a harmonic resonator, a vessel with an opening into a closed space which selects frequencies—sound vibrations from the sounds bombarding it—according to the size of the opening and of the vessel.

Auinger and Odland selected several amphorae with compatible harmonies, put microphones into each, amplified the sounds, and bounced the sound beam off the walls and ceiling. The soundscape in the forum was completely transformed. Not only that, but the mood of passersby seemed to brighten: they smiled and their steps became lighter. Auinger and Odland called their work of sound art Traffic Mantra.

I met Sam Auinger at Ars Electronica in 2011, where he was the featured artist. Born in Linz in 1956, as a child one of his favorite toys was an iron bar which he could strike to make different sounds. His father wanted him to go into business and in college he studied economics and mathematics, but his real interest was music. He learned to play several instruments, including the saxophone, guitar, and drums, and also sang and experimented with early synthesizers. In the 1970s, he was a member of a band and went on tour to San Francisco. “We were a big hit,” he recalls nostalgically.

Back in Austria, Auinger studied computer music at the Mozarteum University in Salzburg, where he was taken on as a special student since he had no formal music background. To bring him up to speed, his tutors suggested he listen to music beginning with the Middle Ages and carrying on right up to the present. This crash course helped him to realize “how music changes have a lot to do with developments in science and society.” Auinger was particularly taken with Renaissance music and the Baroque “besides the most famous Mr. Bach, Corelli,” and others of that era.

When I ask him which modern-day musicians inspire him, he replies, “Morton Feldman.” Feldman came of age in the heady days of the 1950s’ New York art and music scene. A close friend of Cage, his compositions emphasized the worlds of sound rather than of music per se. His friendship with artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Mark Rothko inspired him to write music which focuses the ear on resonant sounds, just as these artists emphasize texture and pigment, the physicality of a painting. “Morton Feldman could organize time in a way I never heard it before,” Auinger says.

Besides Feldman, Auinger passionately admired Cage and “was completely in love with Edgard Varèse and Erik Satie,” as well as the Greek avant-garde composer Iannis Xenakis. Auinger also admires Miles Davis and John Coltrane, whose music he describes as “everything perfect, not one note too much.”

While Auinger was at the Mozarteum, an instructor took the students to church and asked them where the perfect place was to put a clarinet—an instrument that creates a sound close to the human voice. The answer was obvious, although no one thought of it: the pulpit, where the priest speaks. Auinger realized that the “church becomes a sound box. This really got me thinking about sound events and architecture.”

Meanwhile, he was attending events at Ars Electronica, where he finally heard Xenakis—“amazing”—and the wild American downtown guitarist Glenn Branca. By altering the speaker setup Branca produced an “unbelievably distorted barrage of sound.” “Never heard sounds like that before,” recalls Auinger. After a while Auinger began to pick melodies by the Beatles out of the distorted sound. It occurred to him how your “brain and the precondition of everything you have ever heard in your life is important in this whole context because by listening you can be connected with all you’ve ever heard.”

Auinger had found the path he wanted to pursue: “to go deeper into sound than music.”

In America, amphorae were in short supply, so Auinger and Bruce Odland found other objects to act as harmonic resonators. They settled for long lengths of metal tubing with a microphone strategically placed inside. This eliminates hard tones while magnifying others, and transformed discordant street noises into pleasing sounds, inducing an almost meditative state in listeners. It was like a giant didgeridoo played by the city itself.

Then in 2004, they set up five cube-shaped speakers in the World Financial Center Plaza, fed with sounds from tuning tubes of three different lengths. People could actually sit on the speakers, relax, and listen in real time to the sounds made by the Hudson River, at low and high tide, superimposed with all the sound of the harbor with its daily rituals of ferries and helicopters. O+A called this wide-open plaza a sonic commons. “Sound alters mood,” and these sorts of installations “unite people to listen.” In fact, people approached Auinger and thanked him. They had never before been aware of the tides in the Hudson.

“Is it possible to hear Bonn’s history and architecture?” Auinger asks. In Bonn, with support from the city council, he set up an installation beside the railway station, in a rather dingy area full of harsh noises, threateningly empty and quiet at night. He called it Grundklang Bonn, which he translated as Contemporary Soundscape of Bonn. Once again, he used sound tubes to refine the ambient sound, such as the heavy traffic and other infrastructure sounds from railways, highways, and ships on the river Rhine. These refined sounds are played by a speaker in the cube at the foot of the main staircase of the plaza (center right of photograph). A second speaker is in the cube at the top of the left-hand set of stairs, just above. From time to time it played sounds from a water harp actually set in the Rhine, to remind passersby that the city is shaped by this river. “Spaces are reanimated through the energy of sound,” he finds. It was not only the sound that was improved; the area also appeared softer to the eye. Like most sound artists, Auinger emphasizes the connection of eye and ear, whereas too often the eye has primacy.

8.2: Sam Auinger, Grundklang Bonn (Contemporary Soundscape of Bonn), 2012.

Thanks to his work, there is now sound tourism in Bonn. People come to listen to his installations. Auinger advocates that instead of city architects building sound insulation walls beside busy highways, they should make sound receptacles to shape the soundscape.

As for aesthetics, Auinger mentions his “personal perceptions and struggle with form. What is the scope, what is the room for sound, what is the canvas on which I paint my painting? Where is the space in my canvas [for sculpting sound]?” The intangible essence of aesthetics is the “time and quality of research” he puts into a work. In planning a project, he “knows where to begin, but not where to end,” a quality he shares with other creative researchers, especially scientists. The scientific component of Auinger’s work is clear in his use of speakers and harmonic resonators and generally in his applications of acoustics. For his work he consults with architects, whom he looks upon as scientists, and, more recently, with neuroscientists, with whom he discusses how sound is perceived.

At the end of the interview, Auinger looks around the rather bland room we are sitting in—a classroom with a chalkboard, table, and chairs, and nothing on the walls, giving off a flat sound. “Completely uninspiring,” he says. When someone gives a lecture, he continues, they should be able to arrange the room as regards light, temperature, and sound. “It’s a question of aesthetics. How far should you go to have the conditions in which you can actually transform something? I can’t transfer information in this room.” For a face-to-face talk, however, our room suffices, concludes Auinger, ever alert to the visual and sonic possibilities of spaces.

“We can close our eyes, but we

cannot close our ears”: David Toop

Besides collaborating with Brian Eno, Max Eastley, and Scanner, among others, David Toop has been described as one of the “three most influential British music writers of the last three or four decades” by the pseudonymous Guardian music critic Magotty Lamb, who goes on to write that the “prophetic undertow of landmark volumes such as [Toop’s books] Ocean of Sound and Exotica has become harder to resist with every passing year.” Dressed entirely in black—black T-shirt, black jacket, and black trousers—Toop looks like the archetypal middle-aged artist, but he is anything but typical. He exudes calmness and depth and is at ease talking about his journey through music and literature, which many have found inspirational.

Born in 1949, he describes his art education, in which he quit two art schools, as “catastrophic.” He attributes this restlessness to his “desire to cross boundaries—quite promiscuous, much more of that contemporary attitude that to be an artist you could work with any material in any environment.” Music turned out to be “the right form—its routines and framework.”

In 1971, Toop was interested in ecology and bionics—how biological systems could be used in technological design, such as how a robot could be designed along the same lines as a cockroach with its many legs. Visiting Dartmoor with an artist friend, he hung a microphone on a fence and recorded himself playing the flute. Then he played back the tape, expecting to hear his flute. “But actually it was the flute operating in the sphere of the environment. Actually, recording nature was the discovery.” Toop’s subsequent music research flowed from that realization: that anything can produce sound and that that sound can transcend music. For this way of interpreting what happened that day on the moors, he was inspired by the quasi-scientific thinking of the iconoclastic British artist John Latham.

Latham was from the auto-destructive school of art, in company with Gustav Metzger and Jean Tinguely. He was famous for burning books and sometimes eating them. The concept behind his art was the “least event” that defines the “zero moment,” from which everything else follows. One of his early works was produced by using a single burst from a spray can to pepper a white surface with black dots. Art reached its least event in 1951, he asserted, when Robert Rauschenberg displayed a plain white canvas on which the only form was the viewers’ shadows. The following year Cage’s 4’33” premiered, and a few years later the anti-art, anti-commercial Fluxus movement sprang up with its happenings, in which the audience participated, making the work change with each performance. Fluxus can be described as Dada with a purpose, and in its heyday its ranks included Yoko Ono, Joseph Beuys, and Nam June Paik.

Toop’s zero moment occurred on the moors. It was the origin of his timeline, defining where he stood in three-dimensional space. Realizing that “any device can make sound,” he felt “decentered” from traditional music in both space and time.

“In 1971, there was no such thing as sound art, which was a good thing because it’s a contentious term that makes no sense,” Toop says, adding that he once “spoiled the day” at a panel discussion when he said this.

To open up his zero moment, his least event, Toop looked to Cage and to jazz and ethnic music from Africa, Indonesia, China, Japan, New Guinea, and South America. He was intrigued by the instruments of these cultures, especially the alien sound of the sacred flute from New Guinea. The flute is a long piece of bamboo open at both ends and played by blowing across a hole drilled near one end. The sounds it makes play havoc with temporal scales, harmony, melody, and pitch relations as well as sound, “which is what music is all about.” There was a musical vocabulary for all these but, in Toop’s view, “no coherent language for texture, the main feature of twentieth- and twenty-first century music.” Texture in music is intuitive, the overall quality of a piece, a combination of all the above properties.

The sounds the New Guinea flute makes are “based on straight physics,” he says. To understand the physics, he looked into the great nineteenth-century German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz’s On the Sensations of Tone, where he found out about the Helmholtz resonator, also used by Sam Auinger. It makes an ethereal sound akin to that of the New Guinea flute. But texture still escaped him.

I mention to Toop the problem in quantum physics of trying to describe the ambiguous objects of the subatomic world, which are both wave and particle at the same time, using language from our daily world where objects are localized and tangible. Toop agrees with this analogy and adds that we need to get away from object-based thinking and localization. John Latham, he says, believed that it was all an illusion, that events just spring from a “zero moment.”

Toop recalls that in the 1970s people interested in experimenting with music started to move away from the security of straight music and art. The ensuing movement was toward music as episodic and structureless, as a series of events. He mentions Wagner’s huge cyclical operas, which mean more as pagan rituals than as staid opera. Toop wanted “to work as simply as possible in a complex world and produce instruments that can take you beyond the world of senses.” “Now,” he continues, he “works with the computer and bamboo.” The high tech and the low tech, “a polarity of means, quite healthy.”

“Working with a computer, I can create sound works not possible forty years ago,” he says. But even in the age of computers, Toop is delighted that, to some extent, he can still work as he did years ago—as, for example, in his performances in which he uses a laptop together with dry leaves rustling on an amplifying surface.

“Technology is extremely important because it is the expression, or articulation, of the system,” he says. Technology is the reason why the flute produces perfectly tempered scales, while also enabling the player to go beyond this, to work between the notes. “There are many wonderful examples of music that goes beyond that, such as Japanese shakuhachi music played on a shakuhachi flute made of bamboo, both ends open, with finger holes on its length and blown at the end. In contrast to most wind instruments, competent musicians can play at any pitch they choose.” The New Guinea sacred flute, on the other hand, produces its variety of pitches by blowing across a hole. Both instruments operate by straightforward physics, which inspired Toop to join other musicians devising new instruments better suited to “sound making.”

In 1975, along with Max Eastley, who works in kinetic sculpture, he produced an album, New and Rediscovered Musical Instruments. Eastley produced kinetic devices driven by wind or water or some other force of nature to produce variations of the sounds we hear around us. He called these instruments centriphones and hydraphones. The advent of laptops with the software to produce any sort of sound rendered these unnecessary. The laptop itself became a musical instrument of infinite variety.

“Electronic music,” Toop says, “goes back to the sixties, to Stockhausen, for example. Now it’s out of the box. There’s no more programming. The computer pretty much acts like an instrument.” In fact, he continues, “in live performances, performance programs allow you to improvise as you move along.”

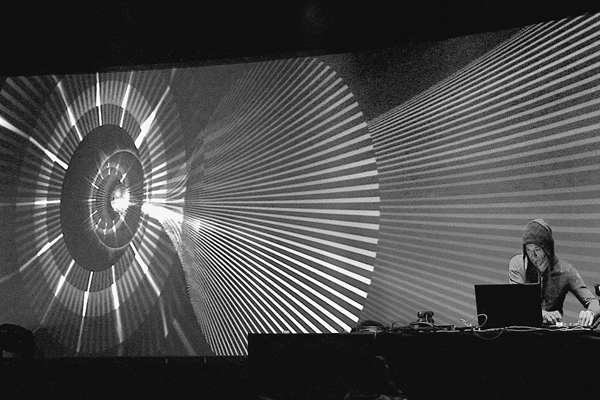

Toop uses a computer, electronics, musical instruments, a sound table, often images, and sometimes voice. The performances elicit multilayered responses—aural and imagistic as well as bodily responses to the rhythms. His pieces can be mournful dirges, evoking eerie images in the mind. Flat Time is a good introduction to his work. In it, Toop explains his musical techniques while playing.

8.3: David Toop, in performance using flute, laptop, and amplified percussion, 2012.

In Flat Time, he explores the connection between John Latham’s work and music, a subject which Latham himself considered the best way to express his cosmology, his view of space and time. This, Toop says, can be explained in terms of a two-dimensional representation. The horizontal axis represents the structure of events—of “least events”—passing through every possible universe, while the vertical axis represents clock time. Occurrences in music are dots in this space that, when projected onto the horizontal axis, have a “zero moment,” and on the vertical axis a time read off a clock.

Musicians live in the event-structured world, says Toop. Improvisation, he feels, is an excellent illustration of Latham’s cosmology because of its lack of formal structure in space and time and its many potentialities. “Each moment has the potentiality to direct it anew,” he says. There is a string of “least events,” commencing with the opening notes. Flat Time is performed by an ensemble of violin, saxophone, and flute, accompanied by Toop on the computer as well as the flute and manipulating material on a sound table—crinkling cellophane, stroking a drum head with a piece of wood, and moving leaves back and forth—not to mention a zither-like stringed instrument amplified electrically and a phonograph record played DJ style.

The listener moves from here and now into the worlds of fantasy and mystery, as well as experiencing the music of very different cultures whose sounds possess an intriguing musicality. The musicians play off one another, sparking a series of “zero moments” in the time and space of the studio.

What he is doing, says Toop, is “putting sounds under a microscope and looking at the grains of the sound.” Today, mixing sounds from different cultures as well as the immediate surroundings has become commonplace among electronic musicians. As the music critic Simon Reynolds wrote, “We are all David Toop now.”

“Toop’s writing always meant for me the freedom—as a writer—to actually leave aside Deleuze, or any theorist du jour as canonized frameworks of legitimization, and to explore instead unexpected, incorrect, and incidental references,” writes Daniela Cascella, who researches sound art.

In the 1980s, Toop turned to writing and produced several key books, including Rap Attack, the first serious study of hip-hop, and in 1984, Ocean of Sound, a meditative, nonchronological, stream-of-consciousness study of the emergence of avant-garde music, from Debussy’s discovery of Javanese music to the present. These are the books, as the music critic Maggoty Lamb wrote, “you’d be most likely to find on Bjork’s bedside table.” Indeed, the Icelandic singer has recently turned to science and technology for themes.

Rap Attack led to invitations for columns and features, and Toop plunged into journalism which for a while pretty much took over from music. Then, just after the publication of Ocean of Sound, his wife committed suicide. Shattered, he drastically altered his life, fed up with journalism and what to him seemed a “relentless cycle of compromises and triviality.” He focused on sound and from then on wrote only the occasional book.

When I ask Toop about aesthetics, he replies, “Intuitional.” He explains, “Intuition is when you’re not thinking about what you’re doing. At a certain level you don’t know what you’re doing. But at a deeper level you do.” In other words, intuition comes with experience, which is essential to improvisation. Performing, Toop adds, “I am always thinking about aesthetics without knowing I am thinking about aesthetics.”

“I have a split personality between critic, in which I am analytical, and musician, in which I am illogical,” he says.

He gives a good example of the intuitive side of music: one does not play a note at a time but clumps of notes, neither does one recall a melody note by note. Music is the perception of organized wholes, or Gestalts. “The analytical faculty,” he says, “can be detrimental to music.”

Toop feels that it is difficult to open out the concept of the creative musician from Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven to include musicians today. The “methods of working have changed dramatically and have become so diverse.” His own musical inspiration began in the seventies with the urge to move toward simplicity and away from the complexity around him. His creative development, he believes, was nurtured by advances in technology and by his writing, which forced him to become more analytical about his music.

We discuss how Toop views connections between art and science, on which he has an interesting take. Duchamp, he says, was a key figure, a “fantastic quasi-scientist.” Surrealism “deeply fascinates” Toop, especially as he has always been intrigued by the unconscious. Among the artists he has studied are André Breton—with his automatic writing, supposedly springing from the subconscious—and André Masson, who championed automatic painting, where the hand paints as if possessed.

As with these artists, says Toop, the irrational, the unplanned, is what lies behind his music. I ask him how he composes and what sort of notation he uses. He replies:

I don’t use any notation in the conventional sense. My experience as a musician is founded in improvisation, where the term “composer” has the meaning of “bringing together.” In other words, I bring together events through the medium of the computer and its software applications, or I use means such as texts, images, and directed improvisation to affect the conditions of performance. In both cases, improvisation is the key, so if a work involves other people, then the act of composition is collaborative.

To him, improvisation is a loosening up of the mind toward experimentation. The closest Toop comes to the rational is his notion of “directed improvisation,” that “least event” or “zero moment” which directs the irrational unfolding of the music.

But, Toop cautions, “today demands proof, despite being surrounded by irrational behavior; there is a pull toward irrational behavior even though we live in a very rational age.” He wonders “what a human being can produce spontaneously.” He sees “a tendency to apply logic to everything, including art,” reducing human behavior to the laws of physics and chemistry, which is indeed what today’s neurocognitive scientists attempt.

Toop sees his own work as combining logic and illogic, science, anthropology, and the theory he uses in his books to explore the fantastic, the mysterious, and the unconscious.

Nature’s own music: Jo Thomas

In 2011, Jo Thomas spent six months at Diamond Light Source at the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus in Oxfordshire. Diamond Light Source is the UK’s national synchrotron facility, a vast circular building like a mini-CERN housing a synchrotron that accelerates electrons to near the speed of light, generating brilliant beams of light which are used for academic and industrial research. Thomas, a sound artist, noticed something else: the tiny rhythmic sounds made by the machine as it monitored the electron beam. To capture them, she put a microphone in the synchrotron, then combined that recording with “ambient sounds such as the synchrotron machinery, people moving—in other words acoustic space, pitches and dissonances, internal rhythms beating.” The result was a thirty-eight-minute sound piece called Crystal Sounds of a Synchrotron.

8.4: Jo Thomas, live performance of Crystal Sounds of a Synchrotron Storage Ring, Diamond Light Source, October 2011.

The mesmerizing sound can lift the listener out of the here and now. The five tracks move from a hum to staccato sounds as the electrons are injected into the beam, creating extraordinary images in the mind. In the sometimes harsh, dry synchrotron sounds, Thomas says, she heard “so much of classical musical forms.”

Crystal Sounds of a Synchrotron Storage Ring won the 2012 Golden Nica for digital music and sound art at Ars Electronica, which is where I met her. Thomas is a bubbly woman with an infectious laugh, contagious enthusiasm, and a great swirl of blond hair. As a child, she tells me, she studied the violin and the viola and learned to compose. She was interested in the potential of recording, too. One Christmas when she was a teenager, she was given a Yamaha synthesizer. She took it to her room and didn’t emerge for days. “I was obsessed with the ways I could change sound with it.” From that point on she was “not really interested in playing tunes but in how sounds change,” as well as the technology of how sound works. To encourage her talent for sound art, her parents arranged a composition tutor for her. She went on to study at Bangor University in Wales which had “incredible sound studios. I was just in there, forever. I never came out.”

I ask Thomas what composers or schools of music inspire her. A long hesitation follows while she anguishes over how to reply. Her answer is intriguing. She can’t put her finger on any musician in particular, although she mentions Bernard Parmegiani, a highly experimental French composer known for his electronic music, along with Karlheinz Stockhausen, who got her interested in “how sound moved.”

Both were born in the late 1920s. No more recent composer comes to mind. Then she confesses that what really interests her is “any music by anyone whatsoever, played on whatever, as long as the performance exhibits skill.”

When I ask how she composes her work, she says that she “sees sound.” She can “paint and draw music, a kind of synesthesia.”

To create Crystal Sounds of a Synchrotron Storage Ring, Thomas worked with two scientists, Guenther Rehm and Michael Abbott, who acted as guides, showing her the audio output used to monitor the beam. She found that her take on sonic information was very different from theirs. One set of sounds which she found intriguing, the scientists considered “rubbish—just problems in the beam line,” malfunctions in the machinery. Nevertheless, she decided to include everything in order to provide as complete as possible a sonic space.

Eventually each came to respect the other’s viewpoint. “We always thought incredibly big. Nothing was ever turned down. This tells you something about science and art. There are no boundaries.” She continues with great enthusiasm, “This is a universe and this is what can happen. It was so nice to think big. I always think big. It’s nice to be accepted for thinking big.” At Diamond Light Source, Thomas was in her element.

When she asked one of the scientists if he had learned anything new from their collaboration, he replied, “No,” but added that it was a “nice union of ideas.” The scientists involved, she says, felt “very creative when they worked with me.”

She has an intriguing take on aesthetics which applies to process as well as finished product. At first she talks around the subject, saying that she associates aesthetics with being “interested in an exchange of ideas.” Then skill enters the picture—how skillfully a piece is made. Then comes the artist’s feeling for the work. “A work has a belief in itself and must be able to exist in its own right.” Finally, the product must involve a “transfer of knowledge, that is, of beauty and skill.” Ultimately, the aesthetic is to do with intuition.

Sound and image: Paul Prudence

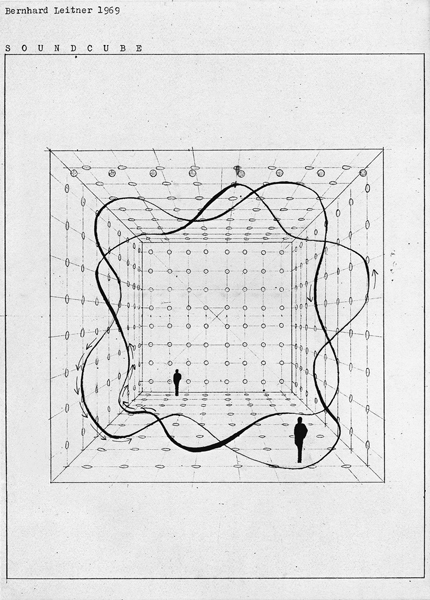

Paul Prudence looks every inch the avant-garde artist. He sits hunched over one or two computers, in jeans and hoodie topped off with a wool cap, driving sounds and images. I see him perform his magic in the vault of a deconsecrated church at Goldsmiths College in London. The audience is in heavy coats, breathing steam. As we watch, he conjures up on a screen universes of whirling, swirling patterns, evoking four-dimensional geometry and diagrams of four-dimensional space-time out of relativity theory, which spin and morph into quasars, black holes, and the Big Bang, all accompanied by booming sound.

Although totally modern, Prudence has a huge respect for his musical predecessors. He started out at the University of Manchester studying textiles, specializing in printed fabrics for couture fashion. “Always a bit of a surprise for people,” he says with a wry smile. He soon realized that was not for him and went to Goldsmiths to do an MA in fine arts.

In fact, as he points out, there is a historical link between fabric design and computers. In the nineteenth century, the Jacquard loom used punched cards to control the weaving process, anticipating the role of punched cards on early IBM computers.

Prudence pays homage to his artistic predecessors, starting with the Swiss Adolf Wölfli and the Scottish Scottie Wilson. Both were early outsider artists who produced highly complex, fantastical designs using pen and ink. A bit later came Oskar Fischinger and John Whitney, pioneers in computer animation, Victor Vasarely, whose work had a strong element of Op Art, with emphasis on geometry and changing forms, and John Cage, a particular inspiration in his efforts to get rid of authorship. Cage’s works continually evolve, each performance differing from the last.

8.5: Paul Prudence performing Cyclotone, 2013.

Prudence soon discovered the Web and found that he was rather handy with computers. “I learned animation packages and started programming, using code and algorithms”—no easy task when you have a minimal technical background. Early on he sensed the “tension between how much randomness within a system can create something that is aesthetically acceptable.” The element of randomness, determined by algorithms, allows him to move away from authorship. Once the performance starts, it is the system, not the author, that produces art.

Prudence often uses two computers linked together, one for sound, one for image. He works with one at a time, moving back and forth. “This creates an element of tension,” he explains. “I can control the amount of randomness, I drive it, but it also has a mind of its own, in a way that creates a performance. I like to be surprised during the performance,” he adds.

He is worried that too many digital artists are concerned exclusively with the technical aspects of their work, ignoring “old conventional ideas of story, of narrative—a beginning, a middle, and an end. Music needs to have a sense of drama.” Audiences sometimes think that the video portion of his performance has been prepared beforehand, rather than being a real-time performance, generated before their eyes. “Quite belittling,” he complains. This differs from the audience’s shock at Cage’s 4’33”. Artists have “a bit of a conundrum,” which is whether “at the start of the show you should announce this is not a video, or just let the audience experience the show.” “Was it important to know that for many of Cage’s open-ended works he had consulted the I Ching?” Cage wouldn’t have cared, Prudence concludes, and Prudence doesn’t either. The work can stand on its own and there’s no harm in giving the audience a bit of a challenge, leaving some questions unanswered.

To program sounds, Prudence makes field recordings in different environments, including industrial areas and kitchens. Then he mixes them, bringing in music from diverse cultures. In this way, Prudence says, repeating the famous words of the music critic Simon Reynolds and with a nod to his eminent co-artist, “We are all David Toop.” “This access to sound, and to software tools, gives rise to nested layers of infinite possibilities. [In this way] I try to create sounds you can see. The product of binding them together is greater than the sum of their parts.”

Although “I don’t interact with scientists all that much,” Prudence continues, his work interests them because it is science-influenced. A fascinating example is the images that his algorithms create. These are generated dot by dot, with each dot used as input for another image or another aspect of the same image, using video feedback loops which mimic what mathematicians call recursive functions that can create fractal diagrams. Thus Prudence discovered that he can produce visual representations of complex mathematical functions using controlled signals. Using a spectrograph, he converts the sounds he produces into visual patterns of intriguing beauty. He has compared these patterns to emergent phenomena, referring to the creation of an ordered image from disordered origins. He has even lectured on this work to mathematicians. This is an example of an algorithm written for artistic purposes, yet capable of generating mathematically interesting results.

When I ask his opinion of the proliferation of disciplines cropping up—video art, digital art, computer art, data visualization, media art, and so on—he replies, “Media art, that’s the catchall term these days. It’s everything, it’s a scary term and doesn’t help.” He adds, “I’m not a category person. Even the art/sci thing confuses me a little bit; I always thought that artists were a bit like scientists and vice versa. My community is very much based on the synthesis of art and science.”

“Aesthetics is complex,” he goes on. “It’s not just about new media experience, but about much deeper modes of understanding and the history of cultures.”

He shifts the discussion to “aesthetic sensibility,” about which he is intentionally vague. “It’s some sort of formal way of putting together sound and visual material that seduces you on a number of levels,” he says. “It doesn’t come out of nothing, it’s based on experience.”

Hyper music, hyperinstruments: Tod Machover

Tod Machover radiates enthusism. His very presence seems to raise the temperature of his laboratory. With a broad smile and a halo of woolly dark hair, he seems possessed of endless energy. A dynamic speaker, his expression can change instantaneously from a smile to a frown when deep in thought, and just as suddenly back again.

“If I had all day every day, I’d just play Bach,” says Machover. In fact, he spends his day composing avant-garde music and opera at the MIT Media Lab, sometimes in collaboration with Joe Paradiso, director of the Responsive Environments Group, and members of other groups. For this he uses advanced interface devices which employ algorithms to enable sensors to respond to gestures and generate the sounds of musical instruments.

Machover also invents musical instruments which he calls hyperinstruments. These use electronics to provide extra power and finesse for professional performers, enhancing the electronic scope of keyboards, percussion instruments, and strings. He has even invented an electronic conductor’s baton.

Machover began thinking about hyperinstruments after hearing the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. “It ideally balanced complexity and directness,” he recalls. The problem was that music like that could only be created in a recording studio. He dreamed of inventing instruments that a musician could use to play such complex music anywhere, combining performance with the limitless creativity of a recording studio.

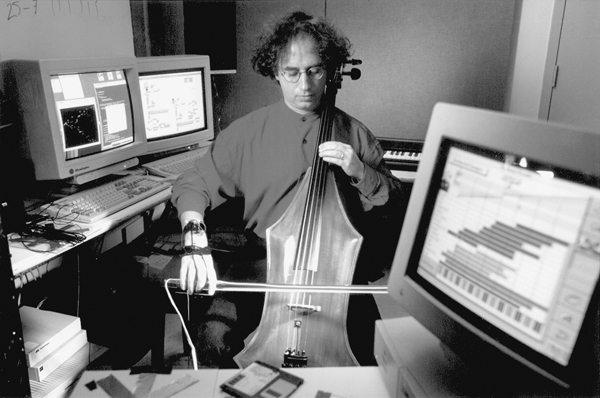

The first instrument he developed was the hypercello. In this, sensors on the player’s wrist, along with a pressure sensor on the bow which responds to his grip, are linked to a radio transmitter, which records the bow’s movement over the strings. The fingerboard is also wired with electronic strips. All this information is fed via an antenna on the cello’s bridge to a Mac computer.

8.6: Tod Machover, Playing the Hypercello, circa 1993.

The hypercello had its debut at the music festival at Tanglewood, Massachusetts, on August 16, 1991, played by the virtuoso cellist Yo-Yo Ma. The piece Ma performed was composed by Machover, whom the critic Edward Rothstein describes in the New York Times as “a virtuoso at computer manipulation of sound.” He writes of the complicated nature of the piece and the sounds emerging from Ma’s instrument as a work “of extroverted eclecticism and sincere self-examination raised to an almost feverish electronic pitch.”

Twenty years on, Machover has largely overhauled the original hypercello. He describes the resulting instrument as able to “morph the cello sound, fracture or congeal complex structures, and shape a magnificent lighting installation, all through subtle changes to cello gesture, touch, and timbre.” Indeed.

Another of Machover’s electronic musical instruments is the hyperpiano. The piano itself is a Yamaha Disklavier, a baby grand equipped with solenoids and optical sensors. Besides storing data, it can receive input from a Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) as well as from compact discs. It can also be hooked up to a computer. Machover and his group put the “hyper” into the piano by adding a Mac minicomputer to do software processing and a parallel visual system that translates the music and the performer’s movements into imagery.

At first glance it looks rather eerie. Besides the keys being played by the pianist, other keys go up and down for no visible reason. The hyperpiano also generates pre-programmed effects, making “a repertoire of colors, lines, and shapes that can morph in and out of textural focus,” as Machover describes it. This “image choreography” responds to what is actually being performed live.

The musical notation for the hyperpiano includes an indication of where the computer enters the performance. When it does, it does not interfere with the pianist. The pianist can also alter the hyperinstrument’s software by using an extra keyboard beside his left hand. “If you’re immune to raw awesomeness, it might be time to listen to the tone clusters based on Gaussian distributions,” Cooper Troxell, reporter-composer, writes in the Kickstarter blog, referring to Machover’s compositions.

Machover’s hyperpiano is a powerful example of the interplay between music and engineering. Not everyone finds Machover’s compositions melodious but, as with Stravinsky, Schoenberg, and others, his day will come. As Machover puts it, “Visual art is easier to grasp than music. Consider, for example, Schoenberg. People complained it had no melody and could hurt your ear.”

Troxell writes of Machover’s opera Death and the Powers, “Tod Machover is one of the strangest composers alive today. While many are content to continue the grand classical tradition of string quartets and symphonies, and others have retreated into the world of purely digital instruments and programs, Mr. Machover has pioneered a unique intersection of electronic and acoustic music across a complex landscape of shifting idioms and textures. His latest landmark achievement was the opera Death and the Powers, which tackles the role of humanity post-Singularity head-on. After the protagonist uploads his consciousness onto a computer, robots take to the stage performing alongside their human counterparts like it’s no big deal. (Note: it is.)”

8.7: A scene from Tod Machover’s opera Death and the Powers, 2011.

Besides electronics and music, the crossover between music, psychiatry, and medicine excites Machover. He envisages “music and medicine as a sort of prescription. Pick the right piece and it homes in on the sweet spot.” Music, he suggests, can be used for early detection of Alzheimer’s and to help Alzheimer’s patients. “Music can tell you something about memory and can be used for pulling back memories.” Machover’s lab also provides ways for physically challenged people to make music, by using gestures or by blowing into tubes. An important concern of the MIT Media Lab is to help people overcome physical problems.

As technology and music come together, Machover sees a blurring of boundaries between different genres with, for example, elements of rap showing up in string quartets. All in all, there will be a greater participation in music, which could result in anything from chaos to mediocrity, as in the era when Bach came on the scene, looked around, and said, “I love this, I love that. I can knit them all together.” “There are so many ideas out there now,” Machover concludes. “A new language is needed to bring them all together.”

Making the computer improvise: Robert Rowe

From early on, Robert Rowe recalls, “Nothing interested me more than music.” As a child, Rowe sang Handel’s Messiah in a choir. He studied classical music and also played in rock bands. While a student at the University of Wisconsin, he came across a Moog synthesizer, which kick-started his interest in electronic music. In graduate school at the University of Iowa, Rowe began to work with computers—indirectly, however. In those early days of computers, he was rarely able to touch one, and instead had to submit his programs on punched cards and return the next day to get the results.

In 1979 he moved to the Institute of Sonology in Utrecht, Netherlands, and was finally able to have hands-on experience. To his good fortune, he was even able to work with one of Stockhausen’s assistants. There Rowe learned to program in devilishly difficult assembly language, which works at the control level of the computer—its architecture, its guts. It’s “an excellent way to learn programming because you really learn what a machine is,” he recalls.

From Utrecht, Rowe moved via the Royal Conservatory in The Hague and the ASKO ensemble in Amsterdam to the Institute for Research and Acoustic/Music Coordination (IRCAM), beside the Pompidou Center in Paris. There he studied with Pierre Boulez. Equally comfortable with music and computers and with a strong bent toward experimentation, Boulez was the ideal mentor. Rowe used his skill with assembly language to experiment with IRCAM’s powerful real-time synthesizer, the 4X machine, and began composing music for musical instruments and computer.

The problem was, Rowe recalls, that the “computer didn’t know what it was doing. It was not taking into account any information from the player. If the player left the stage the computer would go on as programmed.” Computer and player were not interacting. This was difficult, he knew, because performances took place “in a very demanding environment. Working onstage there was zero tolerance.” He wanted to “make the computer musically aware—the computer should make decisions that depended on what the player was doing.”

Thus began a research program that has taken up his life. Says Rowe, “my long-time interest is to have computers involved in real-time performances.” After a ten-year stint in Europe, Rowe enrolled as a graduate student at the MIT Media Lab in 1987. There he was able to pursue his thoughts on interactive systems capable of linking computer and performer into a single unit.

At MIT he worked with Tod Machover, who had also spent time at IRCAM, as well as with Marvin Minsky, one of the pioneers of artificial intelligence (AI). Rowe’s was the first PhD awarded by the MIT Media Lab in experimental music. In particular, he focused on music and cognition. He published his first book, Interactive Music Systems: Machine Listening and Composing, in 1992.

In person Rowe looks like a typical midwesterner, as indeed he is. The bookshelves in his office at New York University are filled with computer science books and he comes over like a scientist. But then I notice the piano in a corner and the music texts. In fact Rowe is now professor of experimental music at NYU, a highly interdisciplinary academic whose passion is to understand how our brains are structured to experience music.

Rowe walks over to a bookshelf, takes out a copy of Interactive Music Systems, and shows it to me. My response is, “This looks like a computer science text.” “Indeed it does,” he replies. “It’s hard-core computer science.” After all, he continues, considering the zero tolerance conditions of working onstage, any scheme that links computer and performer requires mathematical precision.

Traditionally there are two elements in music-making—the player and the instrument. Rowe adds a third, the computer which responds to the sounds and/or gestures (via sensors) of the performer, using an algorithm which is—amazingly—capable of improvising in specified keys so as to complement the performer’s own “live” music. Rowe describes this intriguing interactive process thus:

The computer is (at least in my music) making decisions itself as to what and when to play, but there are large-scale changes in behavior (state changes) that are triggered at certain points in the piece. I have done that automatically as well, where the computer is looking for certain cues that tell it when to change state, but often just advance through those manually, usually one every 30–90 seconds. Other composers play a more active role in changing parameters, or may do even less than me and just be watching the software to be sure it is operating correctly.

This way of working requires a change in musical scoring to indicate where the computer enters, with an algorithm for particular notes. For example, with the Yamaha Disklavier, the pianist depresses keys while other keys play in response to the computer. Sometimes the performer will take his left hand off the keyboard to manipulate a laptop to alter the algorithm, which at first sight looks rather surreal. Rowe’s music is a remarkable give and take between performer and computer, each responding to the other in complementary ways. It is a giant step toward integrating human and computer, removing completely any trace of an interface.

“Are there fundamental rhythmic structures in the brain?” Rowe wonders. Rowe’s interest in music and cognition and computer models of thinking has led him to explore whether we are born with structures hardwired into our brains which possess rules to process input information provided by our environment. This could be why we develop a preference for music from our own culture while finding music from other cultures less accessible.

Today so many people around the world are immersed in Western music that it is difficult to find these basic structures, these human universals. This question attracts the attention of scholars across a wide spectrum, including specialists in musicology, computational modeling, perception, cognition, neuroscience, and mathematics. Rowe insists that the tools are there in other disciplines. To avail himself of them, he works with Godfried Toussaint, a mathematician whose speciality is mathematical and computational aspects of rhythm, and Gottfried Schlaug, a neuroscientist. Both are also musicians, Toussaint a percussionist and Schlaug an organist. The three have written a series of papers putting together a mathematical model of rhythmic similarities among different cultures, searching for something in common among them. The neuroscientist’s input includes analysis of the brain using ƒMRI. A key issue is how to program a computer to seek out basic structures in the brain that respond to music of a particular culture, says Rowe.

This seems a bit reductionist, bearing in mind previous attempts to simulate thinking using a computer. “Correct,” he says. “But you have to start somewhere. These are classic AI problems,” AI being a field of study in which he detects a resurgence of interest.

I bring up A. Michael Noll’s computer program which produced Mondrian-like paintings that 59 percent of the public preferred to the real Mondrian. Rowe notes that this ought to be looked into, that there is something in Noll’s computer-based art that must trigger an aesthetic response in the brain neurology of the observer.

A similar example is the work of David Cope, an American researcher looking into what AI can tell us about musical intelligence. Cope spent many years trying to model Bach’s music. “It was a valiant attempt,” Rowe says, in that “many people who had not heard Bach before couldn’t tell the difference” between computer-generated music produced from Cope’s model and real Bach. What AI does, Rowe continues, “is to reduce the distance between where you are and some sort of goal, e.g., aesthetics in a music program.”

In his work Rowe collaborates with scientists with whom he feels a rapport as one of the new breed of artist, being very much a scientist/musician himself. Clearly scientist and artist alike benefit from this relationship. Rowe goes even further, insisting that there is “more of a payoff for the scientific side of the collaboration.”

Rowe sees a great future for work such as his because “more and more people are thinking computationally about what they do.” He passionately believes, however, that “truly creative thinking will always remain beyond the power of any machine.” In his faculty profile he states his position thus:

Music is and will always remain a fundamentally human endeavor, but technology has frequently had the power to significantly change and shape how we experience music, and I believe the process of trying to help a computer become musical enables us to better understand the true essence of the art form.

Symphonic form in a digital world: Tristan Perich

Tristan Perich is a maestro of electronic music, though in the case of his compositions, sonic art can also have a strong classical input. Slight of build with long sideburns, he is somewhat intense but not manic, easy to converse with. He grew up surrounded by art created by his father, Anton Perich, a filmmaker, photographer, video artist, and pioneer of computer art, who was part of the art scene that revolved around Studio 54 and Max’s Kansas City in New York.

Tristan focused on the piano, but from an early age he wanted to become familiar with a wide range of instruments including the cello, violin, guitar, and flute. He “wanted to see what they are and understand the mechanics of vibrating strings.” He was also fascinated by science, inspired by Brian Greene’s book on string theory, The Elegant Universe, and Douglas R. Hofstadter’s classic on computer science and its relationship to music and mathematics, Gödel, Escher, Bach. Torn between computer science, mathematics, and physics, he went to Columbia University and studied them all. He even attended one of Greene’s courses, where he was so carried away with enthusiasm that he suggested a collaboration with Greene on mathematics and music. There was no response.

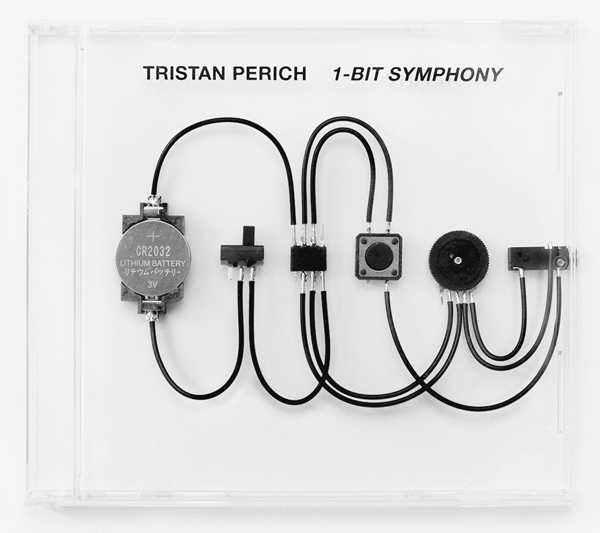

8.8: Tristan Perich, 1-Bit Symphony, 2009.

Perich then enrolled in the Interactive Telecommunications Program at New York University, which focuses on imaginative ways to use communication technologies, particularly in artistic work.

“It is possible to create a rich sound composition with 1-bit audio, a 1-bit symphony,” says Perich. In his electronic music he uses 1-bit circuitry, “bit” being a contraction of “binary digit,” the minimum unit of information in electronics, which can take the values of zero and one, off and on. Circuits made up of 1-bit electronics go back at least to the early digital Casio watches. 1-Bit Music, produced in 2004, consists of a single electronic circuit set in a CD case with a built-in headphone jack. Perich programmed the microchip, assembled the circuit, and marketed the whole package as a limited art edition. The rhythmic electronic riffs are pleasing, even soothing. Five years later he produced the more ambitious 1-Bit Symphony, a symphony in five movements, an electronic composition on a single microchip housed in a transparent CD case. You open the case, plug your headphones into the built-in headphone jack, and the music, which is written in code on the chip, begins to play. Strangely enough, it sounds rather grandly symphonic. “With electronic sound I can create any sound imaginable,” he says.

Why one bit of information, the smallest amount possible? As a student, Perich had studied the history of mathematics and science, and was particularly intrigued by early attempts to reduce mathematics to the fewest statements couched in numbers, the atoms of mathematics. In quantum physics he saw a similar minimalism in the atoms of nature. In music he was inspired by the minimalism of Philip Glass. “Just two notes oscillating back and forth, that’s the musical material.” He also admires the work of Steve Reich. He speaks of his “phasing process. Things go in and out of phase; takes ten minutes, that’s all you’ve been listening to.”

He expands: “You can see the aesthetic from afar, but then you can also see how it’s built up. I find that inspiring, how music applies to the same part of the brain as science. All similar stuff, music, art, mathematics—dependent on basic building blocks.” All this is embedded in Perich’s 1-bit music, built up of information atoms. “Simple stuff is the most pristinely beautiful stuff,” he says dreamily. This is also why Bach’s music so inspires him—it’s clean, pure, and sublime.

For a while Perich turned away from electronics and began composing in the classical style. “Electronic music seemed to have nothing tangible to it, no characteristics of, say, the piano,” he recalls. Then he began to think about putting actual instruments together with electronics.

By electronic instruments he had in mind speakers. After much experimentation, he worked out a unique way to do this. He connected the speakers to a circuit board with a single chip which sent electrical signals, making the membranes vibrate. In other words, he found a way to convert electricity into sound. He also composes the instrumental music. His understanding of the basic physics and mathematics involved in vibrating surfaces and also of computer science enabled him to do all this himself.

He now composes for speakers together with pianos, clarinets, flutes, and percussion. He programs the electronics driving the speakers to work in tandem with the music, so that what he encodes in the circuit boards correlates to what the musicians play. The results are more like music than random sounds, in that they can be melodic and the circuit input is not just rhythmic accompaniment.

Perich tells me that his compositions spring from improvisation, the mind at play—usually at the piano, which is his main instrument. He contrasts this with other composers who use algorithms, which introduce complications. “There’s a difference between process being part of the inspiration or the tool set that you have, and process being a determinant.” He prefers the former.

Perich thinks out each stage of his work. Although the code he writes for the chips is logic, he writes it “with music in mind.” The scientific input, however, ends with the programming. The music itself is intuitive.