84

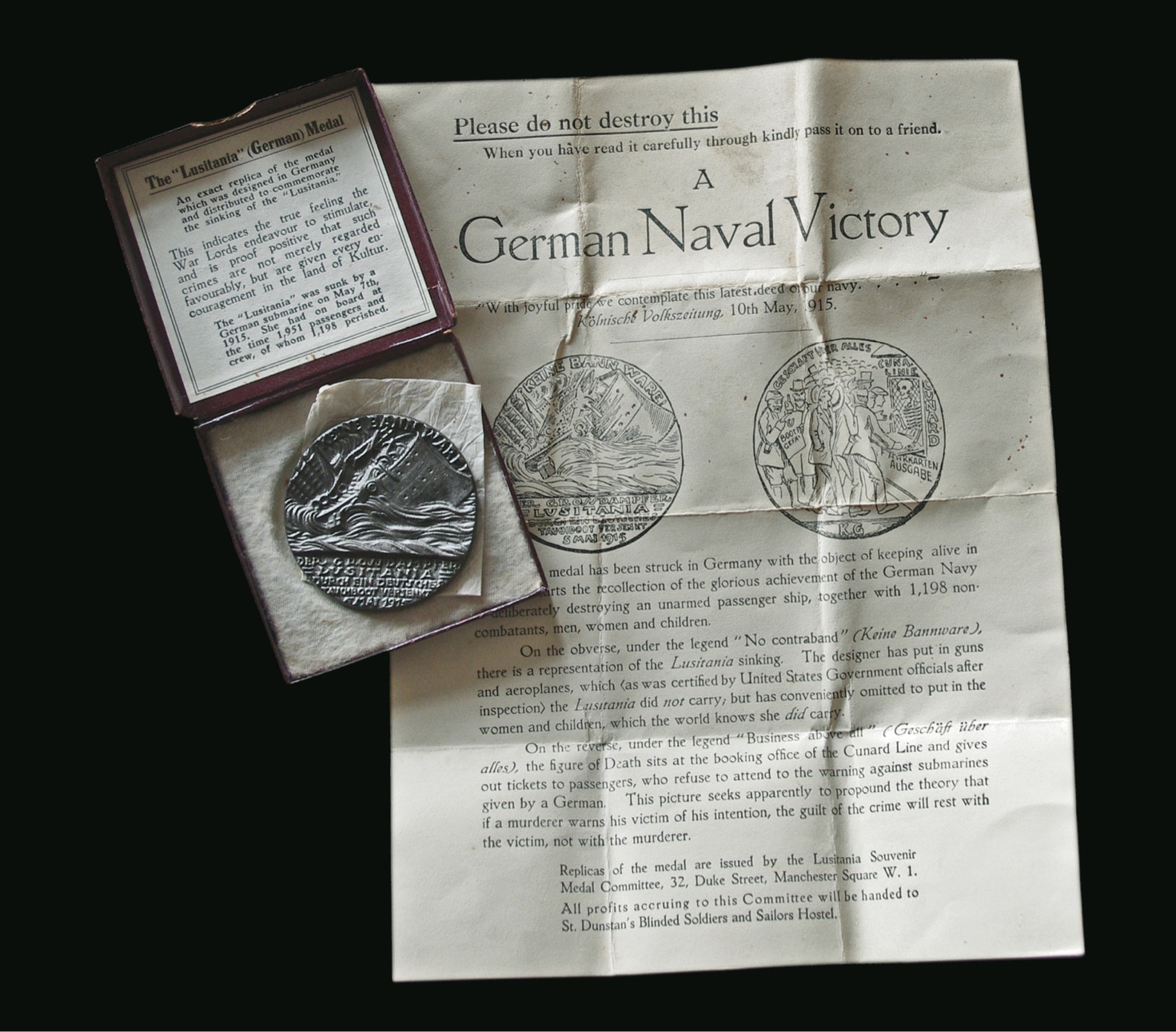

Lusitania medal

THE STRENGTH OF the Royal Navy in the North Sea and English Channel was such that it could dictate terms to all shipping in the region. With Germany dependent upon its North Sea ports, the British were in the strongest position possible and from November 1914 operated a blockade that effectively sterilized the North Sea to any trade with their enemies. First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill was also insistent that there should be an aggressive response to any U-boat sightings by merchantmen. Faced with starvation and the suppression of war materiel brought by neutral shipping, the Germans countered with an announcement on February 4, 1915, in the Imperial German gazette, the Deutscher Reichsanzeiger:

All the waters surrounding Great Britain and Ireland, including the whole of the English Channel, are hereby declared to be a war zone. From February 18 onwards every enemy merchant vessel found within this war zone will be destroyed without it always being possible to avoid danger to the crews and passengers.

Neutral ships will also be exposed to danger in the war zone, as, in view of the misuse of neutral flags ordered on January 31 by the British Government, and owing to unforeseen incidents to which naval warfare is liable, it is impossible to avoid attacks being made on neutral ships in mistake for those of the enemy.

The Germans were in a position to back up their threat through the use of their submarine fleet. In 1914, there were just twenty-nine U-boats (Unterseeboots), but with the impotence of the German High Seas Fleet came reliance on these sleek vessels as an effective threat to Britain’s naval dominance—and an exponential increase to a high of 142 submarines in 1917. Fear of the U-boat had led to a rise in the use of neutral flags by British vessels—but with the German announcement of unrestricted submarine warfare came the probability that such vessels would still be targeted.

The RMS Lusitania, one of the largest and most impressive ships on the Cunard transatlantic fleet, had flown a neutral flag on January 31 when faced with reports of German U-boats in the vicinity. The giant liner was stalked again in March in the Western Approaches. But when it sailed from New York to Liverpool in May 1915, the liner’s luck had finally run out. Returning from New York on May 7, 1915, while off the coast of Ireland the Lusitania was struck by a single torpedo fired from a German U-20. The massive ship sank in eighteen minutes, with the loss of 1,198 lives—of whom 128 were American. The outcry and negative backlash against the Germans were huge.

Our object is a British propaganda medal, manufactured in cast iron and paid for by the American department store owner, Gordon Selfridge. Some 300,000 of the medals were cast and issued with a leaflet that decried the “German Naval Victory.” The casting is a replica of a bronze medal that was created by the medal maker Karl Goetz. Goetz had already issued bronze medals that had condemned British activities on the high seas; his medallion, bearing the date May 5, 1915, illustrates the figure of death selling tickets for the liner while others look on, reading a newspaper carrying the warning issued by the Imperial German Embassy in New York against sailing across the Atlantic. Above the figure reads Geschaft über Alles (business over all). The other side of the medal shows the Lusitania foundering in the Atlantic, with the words keine Bannware (no contraband) prominent.

Goetz’s medal had the wrong date; this was reproduced faithfully by the British, who claimed the date was evidence of a preplanned action. The leaflet commented bitterly:

The designer has put in guns and aeroplanes, which (as was certified by United States Government Officials after inspection) the Lusitania did not carry, but has conveniently omitted to put in the women and children, which the world knows she did carry.

The sinking was universally condemned on both sides of the Atlantic. The Lusitania had been constructed to be a naval auxiliary cruiser if necessary, but no guns were fitted. The hold did contain cargo, which included small arms ammunition, but did not carry larger weaponry. The arguments as to whether the Lusitania represented a legitimate target still resonate down the ages. But the great loss of life, and the propaganda victory scored by the British, were a disaster for the Germans. The submarine campaign was scaled back; the Americans were enraged. The sinking of the Lusitania would be a cause célèbre that would start the United States on a track that would ultimately see it join the war two years later, and with it the promise of greater numbers of men and materiel crossing the Atlantic than could ever have been envisaged at this early stage of the war. It was a costly mistake for the Germans.