For the two months following the incident at City Hall Plaza, whenever Stanley Forman covered an event in South Boston, protesters pointed him out and shouted, “He’s the one, that’s him who took the picture.” Once, at a fire, he had to be escorted to safety. “In Southie, I was shit because of the picture,” he recalls. The opponents of busing knew he had taken the photograph, and they knew how much damage it had done to their cause. Forman’s photograph did not end the resistance to busing, but it marked a turning point from which the movement could not recover. However strenuously the anti-busing movement emphasized issues other than race, the photograph shattered the protesters’ claim that racism did not animate their cause and that they were patriotic Americans fighting for their liberties. The photograph had seared itself into the collective memory of the city and installed itself in the imagination of both blacks and whites.

Stanley Forman was in Amsterdam in late April 1976, accepting the World Press Photo Award for his fire escape photos from a year before, when he learned that he had also won the Pulitzer Prize for spot news photography. There was a party in the Herald offices on May 3 when the official announcement came. He received telegrams and phone calls congratulating him. He left the celebration early to get to the Garden for the Bruins-Flyers game. And then, the next day, he was back to work. He covered a bomb threat, went to a protest by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, and called it a day.

Already, there was buzz that his flag photograph would win a second Pulitzer and carry off every other top award. Dave O’Brian, a former Record American reporter and now media columnist for the Boston Phoenix, came to the defense of his former colleague who was the target of barbs from jealous newsmen:

So Herald American photographer Stan Forman (who, the paper tells us, still eats his breakfast and walks his dog just as if nothing had happened) won the big one. Having copped a Pulitzer Prize for his stunning photo sequence of 20-year-old Diane Bryant falling to her death after the collapse of a Back Bay fire escape, Forman, at the tender age of 30, is now a bona fide star.

Of course, the office cynics were saying for a while that for Forman it would surely be all downhill from here. The pictures were great, the cynics conceded, but only because Forman just happened, as they say, to be “in the right place at the right time.” And since he was using a motorized camera, they were saying, it didn’t even take much skill to get those admittedly terrific shots.

But I wonder what they are saying now that Stan Forman is a serious candidate for a 1977 Pulitzer. Indeed, Forman’s shot of an anti-busing demonstrator assaulting black lawyer Theodore Landsmark with the American flag may, in terms of its obvious symbolism, be an even greater photograph than this year’s winner. Again, of course, Forman was lucky. But this time he was one of many who were snapping their shutters as the Landsmark attack occurred and yet was the only photographer to come away with the photo of the event. So you begin to wonder if being “in the right place at the right time” might be the result of more than just luck.

This time around, Forman kept the presentation simple, submitting only The Soiling of Old Glory as a single, simply mounted image. A year later he learned that he had won a second consecutive Pulitzer Prize for spot news photography.

In Boston, one African American artist responded to the image almost immediately in the only way he knew how, with three large (two were 48"×70" and one 70"×48") acrylic works depicting the assault. Dana Chandler grew up in Roxbury and graduated from the Massachusetts College of Art in 1967. He became active in the civil rights movement and involved with Artists Against the War. Chandler began teaching at Simmons College in 1971 and in 1974 had studio space and taught at Northeastern University, where he established the African American Master Artists-in-Residency Program. In 1976, Northeastern’s art gallery featured Chandler’s exhibition “If the Shoe Fits, Hear It.” Shortly after the exhibition closed on April 2, Chandler, like everyone else in Boston, saw Forman’s photograph. By December he had completed his canvases.

Chandler’s brightly colored works used the flag as a motif in depicting three moments: the original assault, the attack with the flag, and a portrait of Landsmark afterward. It is clear from pictures taken at an unveiling of the work at Northeastern, an event attended by Landsmark, that Chandler consulted several of Forman’s photographs. The pictures on the bulletin board to the right are in reverse chronological order and show Landsmark immediately after the attack, the assault with the flag, and the beating prior to the flag’s arrival. Newspaper accounts of the assault are also posted.

Dana Chandler, Landsmark paintings, 1976 (NORTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS)

The paintings are three canvases that flow together. In choosing to execute a triptych, Chandler was tying his subject to the tradition of Christian art, which often featured three hinged panels that depicted the Crucifixion. In the first panel, the flag unfurls like the wings of a predator as Landsmark is kicked and stomped. He falls to the pavement, which Chandler painted red, green, and black, the colors of the black nationalist flag first adopted in 1920 and put to various uses by advocates of black and African liberation since. It is possible that the foreground figure on the right expresses horror, but no help is forthcoming. In the third panel, that figure now faces the viewer. Unlike in the photograph, Landsmark is eyeing his attacker. Also unlike in the photograph, the man holding him from behind is also beating him. In both panels, hands are central elements: fists fly and fingers curl. Landsmark uses his hands to steady himself, but his black hand, made prominent against the white stripe, will not stop the flag from reaching its target. In the portrait of Landsmark that is the middle panel, his face is bandaged with the flag’s stars. He glares at us, enraged. The white stripe of the flag flows across the three panels, tying them together. The event, Chandler said, proved “that the American flag is in fact a weapon against black people.”

Dana Chandler, Landsmark paintings, 1976 (NORTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS)

For one black family, the incident and photograph forever shaped a child’s identity. Janus Adams, journalist, historian, producer, and, it so happens, Ted Landsmark’s cousin, recalled the impact of the image on her daughter, who was only in nursery school at the time of the incident, but who later said that the picture marked her racial awakening. Adams recounts what her daughter told her: “That incident made me understand there was something beyond being mean spirited. It was something so random. There was no reason for it. He [Landsmark] didn’t do anything to anybody. A lot of people don’t have that concept of hatred just for the sake of hatred, but it existed for us as black children. In America . . . black people and white people walk on the same road but on different sides of a wall. To us race is something we don’t have the privilege of ignoring. I learned young to look beyond what things seem to be. There is a reason why people get attacked for nothing.” To this day, Adams recalled in 2004, “our family is stabbed to its core when that photo crops up.”

We might expect that Forman’s photograph would haunt the black community, but its impact also reached deep into South Boston itself. Michael Patrick MacDonald grew up in the Old Colony projects, and his memoir, All Souls: A Family Story from Southie, is a searing account of life in the neighborhood. McDonald’s mother saw the photograph on the front page of the Herald American and said, about her neighbor taking aim with the American flag, “What a vicious son of a bitch.” “Busing is a horror,” she said, “but this is no way to fight for it. People like that are making us all look bad.”

MacDonald’s account continues, and it provides a different perspective on the anti-busing movement:

[Ma] said she was starting to think that some politicians in Southie were almost as bad as Judge Garrity himself. She thought they might be stirring things up in the drugged-out minds of people like the teenager in the Herald. “And the kids are the ones suffering,” she said. “Especially the ones who can’t get into the parochial school with the seats filling up and the tuitions being raised.” She said she felt she was kicked in the stomach every time she heard Jimmy Kelly talking about niggers this and niggers that at the Information Center where she’d been volunteering. She said she couldn’t get used to that word, no matter how much she hated the busing. Then there were the South Boston Marshalls, the militant group connected to the Information Center. We all wanted to stop the busing, but sometimes it was confusing. One day you’d be clapping and cheering the inspirational words of Louise Day Hicks and Senator Billy Bulger, and the next day you’d see the blood on the news, black and white people’s blood. And here was a black man being beaten with the American flag on the national news.

MacDonald’s mother was not alone in her feelings, and in elections the following year voters turned away from anti-busing militants. Both Louise Day Hicks and John Kerrigan lost their City Council seats. Elvira “Pixie” Palladino, a firebrand from East Boston and an ally of Kerrigan who split with Hicks over tactics, had been elected to the School Committee in 1975 but now lost her seat. A moderate, Kathleen Sullivan, received the most votes for the committee. But even more remarkable, John O’Bryant was elected. His last name may have sounded Irish, but O’Bryant was black, and he became the first black to be elected to the School Committee in a citywide election.

The tensions in the schools seemed to have abated as well. “Truce in Boston,” declared Time about opening day in September 1976. No helicopters; no sharpshooters; just pockets of protesters. Eighteen months later, a reporter visited South Boston High School and found that the “open hatred and fear has finally dissipated” and that “only a lingering uneasiness” remained. A black student said, “It’s a lot better than it was before.” A white student admitted that coming to school was better than standing on the street corner. Teachers had gotten control of the corridors, where so much mischief took place in 1974 and 1975, and regained an enthusiasm for teaching in a more relaxed atmosphere. “Desegregation did not carry with it the end to effective and solid education,” said one teacher. “In many respects it meant the beginning of it.”

The report also pointed out that there were few students in the classrooms and that this fact, as much as anything else, explained the easing of tensions. Between 1974 and 1977, the percentage of white students in the Boston school system declined from 55 percent to 42 percent. By 1980, it was down to 35 percent, and by 1987, 26 percent. Rather than accept desegregation, the whites who were able to left the system—for parochial schools, for the suburbs if they could afford it, for no schooling at all. A debate over “white flight” emerged, a debate that was in effect a referendum on the consequences of busing. Supporters of busing argued against a correlation between busing and movement to the suburbs by white families. They citied studies by political scientists and sociologists who claimed to find “little or no significant white flight, even when [busing] is court ordered and implemented in large cities.” But the preponderance of the evidence seemed to support the reality of white flight in situations such as Boston’s: court-ordered busing of whites as well as blacks, a large district, high black enrollments, and available white suburbs. Moreover, there was anticipatory flight as many whites left before desegregation plans took effect. However much supporters of desegregation wished it not to be true, in Boston, according to Ronald Formisano, “white flight could account for at least half of the total white loss from the schools during 1974–1980.”

Responding to the easing of tensions, Garrity relinquished control of the schools, first giving the responsibility for compliance with the court’s order to the state board of education and then, in September 1985, returning authority over the educational system to the School Committee. By then, there was a new mayor in Boston, a symbol of a new urban politics that would seek to revitalize Boston and turn the city around. Less than a decade before his election in 1983, it would have been unimaginable that an Irishman from South Boston, an opponent of busing, could have become mayor. But the mayoral race between Ray Flynn, the victor, and Mel King, the black activist and former legislator who himself ran a vigorous and engaging campaign that garnered both white and black support, reenergized a defeated city. Voters believed, according to the New York Times, that “after years of racial strife and neglect of the city’s neighborhoods, the city is changing for the better.”

Flynn, the son of Irish immigrants, graduated from South Boston High School in 1958, and after attending Providence College he returned to South Boston and was elected a state representative in 1968. He was as virulently opposed to busing as Louise Day Hicks and William Bulger, but he chose a more moderate path when he refused to sign the Declaration of Clarification and focused his attention more on the topic of the police presence in South Boston and support for a biracial parents’ advisory council than on the racial fault line of desegregation. Bulger later said that Flynn had a “certain fluidity of principle . . . and could read the wind like a wolf.” By 1983, the sail was up for the wind of moderation, and it swept Flynn into the mayor’s office. Once there, he never slowed, stopping on his runs to play basketball with black kids in Roxbury, or giving McDonald’s gift certificates to sanitation workers at Kenmore Square, or visiting the cafeteria at South Boston High School, where the students cheered. In his inauguration speech, he invoked Lincoln: “Boston has for too long been a house divided against itself. We have endured the worst sort of polarization and confrontation, but our resolve now is to bind old wounds, put the memories behind us, and carry worthwhile lessons into the future . . . This is a time for hating the violence and discord of the past. It is a time for loving the city and all its people.”

Less than two years after Flynn’s election, Boston paused to look back on the tumultuous events of the seventies when J. Anthony Lukas published Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families. It was seeing Forman’s photograph that led Lukas to start his project. “In that single image he saw his beloved Boston being torn asunder,” recalled the journalist Samuel Freedman. Seven years in the research and writing, Lukas’s book brought to life the struggles of desegregation by focusing on three representative families: the Divers, a liberal suburban Yankee family; the McGoffs, Irish Americans from Charlestown; and the Twymons, a widowed black woman and her six children. Through their stories, and the stories of dozens of others, Lukas painted a stunning, textured portrait of Boston in crisis. He wrote breathlessly and with deep empathy for his subjects, and in Boston’s story he found not only himself but also a larger story: “I believe that what happened in Boston was not a random series of events but the acting out of the burden of American history.”

On September 28, 1985, a town meeting on race and class, organized in conjunction with the publication of Common Ground, drew five hundred people to the Kennedy Library on a Saturday night. The many panelists and commentators covered the spectrum of the busing crisis: Paul Parks, former Massachusetts secretary of education; Robert Kiley, former deputy mayor; Thomas Winship, former Globe editor; assorted professors, ministers, parents, and activists. At one point, Elvira “Pixie” Palladino spoke, and her anger still flashed. She denounced forced busing as a class issue and lamented how few anti-busing representatives were at the forum. “The only common ground we’re ever going to have is that we love our kids,” she declared. Knowing how the largely white, middle-class, liberal crowd must have felt about her, she asked, “How many of you are going to love me, no matter what color I am?” From the audience, Wayne Twymon, who had been bused to Brighton High School, said softly, “Pixie, I do love you.”

Ted Landsmark was also one of the panelists. Landsmark had left the law to pursue his other passion, art education. Now dean of graduate and continuing education at the Massachusetts College of Art, Landsmark was one of the leading black educators in the state. “I suppose for the rest of my life I’ll always be thought of in the context of a photograph,” he said, and then he drew a laugh when he commented on how he was an amateur photographer and, although he obviously didn’t take the picture, he felt as if he too had won a Pulitzer. Landsmark pointed out that his only involvement in education issues came indirectly as a result of the photograph and that his work had been related to affirmative action in the workplace.

The importance of the publication of Lukas’s book, he thought, was not so much that it made Bostonians look back as that it encouraged them to think ahead about “what it is we want to do at this point.”The most significant common ground, he said, “is that we have committed ourselves to being in Boston for the long haul and have made a basic and fundamental commitment to Boston.”

What disturbed him most was the composition of the room. “I don’t know that I often agree with Pixie,” he remarked, “but there is one thing she says that really does strike me, and that is that there are some people who have been heavily involved in this whole thing who aren’t here.” He lamented that “the number of people of color is very small,” and he speculated about the reasons why they weren’t at the town hall and maybe had given up on Boston completely. Whenever he traveled, friends said to him, “Oh yeah, Boston, you’re still there? That city is really racist.”

Racist or not, Landsmark said, it seemed clear that Boston had limited opportunities for blacks to grow personally and professionally. Few served on corporate boards of banks or insurance companies; few had art exhibitions of their own. “How many of you know a black realtor in this town?” he asked. What was needed was for the private sector to respond and provide opportunities—and role models—not only for black children but for white children as well. He reminded the group that nearly ten years earlier, in the aftermath of the assault, he had remarked that “the chances of any of the kids who attacked me ending up on a major corporate board in Boston are as slim as any black kid ending up on a board.” Landsmark made the same point as Palladino: “it’s a matter of class that we are looking at.” And it was up to the people in that room not to celebrate having survived the turmoil of the seventies but to make progress for the future by helping to open up opportunities and possibilities.

In March 1990, emotions again flared over Common Ground, which had been adapted into a two-part made-for-television movie. The film was long and melodramatic, and it offered stereotypes where Lukas had provided nuance. It also distorted events, none more so than the assault on Landsmark. In the movie, Landsmark is attacked not by students but by parents. He is beaten until he is nearly unconscious. The man carrying the flag is wearing a Boston Celtics jacket, and he lines up the staff, taking careful aim. The camera is located behind the victim, placing the viewer in the position of Landsmark as the staff is thrust into his face. Landsmark is left lying unconscious on the ground.

While the film version may have sketched the essence of the larger conflict over busing, no one at a screening in Boston approved its more sensationalistic aspects. Palladino called it “a piece of pornography,” and Jim Kelly told the film’s producer, “You don’t know what you are talking about.” Landsmark thought the film might generate “a lot of anger and anxiety.” Always thinking about community, he suggested that the producers donate some of their profit to the city “to further the healing process that is going to be sorely tested by this film.”

That healing process hadn’t yet reached Landsmark’s flag-wielding assailant from 1976. Joseph Rakes found himself running out of hope. The photograph may have made him a momentary hero among his least reflective friends, but very quickly he felt only despair. In 2001, Thomas Farragher, a Boston Globe reporter, spoke to Rakes and two of his brothers. It was the first time Rakes had spoken to the press about the incident. One of his brothers said that after the photograph appeared, “he went into a shell . . . He thought everybody was looking at him. He didn’t want to talk about it. It was a bad time in his life. Everybody knew him as the ‘flag kid.’ And that can wear on you year after year. He hated it.” Joseph Rakes said that he was in a state of “blind anger” over busing: when it started, “it was ‘You can’t have half your friends’—that’s the way it was put towards us. They took half the boys and girls I grew up with and said, ‘You’re going to school on the other side of town.’ Nobody understood it at 15.” He explained to Farragher, “There was no thinking whatsoever. It was more rage than anything. I didn’t know until it was over what had happened. I remember turning and running. I mean, when you think about it, that Stanley Forman had a quick finger.”

Essentially, Rakes kept running. He graduated in 1977 and bounced around in different minimum-wage jobs. In 1983, he got into a fight with Thomas Dooley, who was dating Rakes’s sister. He smashed Dooley over the head with a lead pipe. Ten days later, Dooley died, but not before identifying Rakes, who fled. For five years, Rakes ran, rumored to be in Florida and the Bahamas. In 1988, he finally turned himself in, but by then evidence and witnesses had disappeared. The prosecution’s case had become stale, and first-degree murder charges were dropped. Rakes started a construction job, married a South Boston girl, and moved north of Boston. When Farragher spoke to him in 2001, he was working on Boston’s Big Dig. Rakes lamented the loss of Southie—of close family ties and kinship networks and ethnic loyalties. Now, he said, it was simply South Boston. But one artifact from his youth remained in his possession: the flag he carried that day sat folded in a cabinet at home.

As Rakes tried to reassemble his life, the American flag again became a national flashpoint. In 1989, a divided Supreme Court issued its decision in Texas v. Johnson. The case stemmed from an incident at the 1984 Republican National Convention in Dallas. Gregory Lee Johnson, a member of the Revolutionary Communist Youth Brigade, a radical Maoist organization, participated in a political demonstration in protest of the renomination of Ronald Reagan and corporate businesses in Dallas. The rowdy protesters shrieked obscenities, disrupted businesses, and committed minor acts of vandalism, including taking a flag from outside a bank. When they reached Dallas City Hall, Johnson took out the flag, poured kerosene on it, and set it ablaze. Protesters chanted, “America, the red, white, and blue / we spit on you.”

Johnson was charged with violating a Texas flag-desecration law passed in 1973. He was convicted, and the conviction was upheld by the state court of appeals. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, however, reversed the conviction, and the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that decision. Writing for a 5–4 majority, Justice William J. Brennan argued that Johnson’s actions “were symbolic speech protected by the First Amendment . . . The expressive, overtly political nature of this conduct was both intentional and overwhelmingly apparent.” Rejecting Texas’s argument that desecration of the flag is a crime because it destroys a “symbol of nationhood and national unity,” the Court held that “if there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable . . . The way to preserve the flag’s special role,” Brennan concluded, “is not to punish those who feel differently about these matters. It is to persuade them that they are wrong.”

In his dissent, joined by Justices Byron White and Sandra Day O’Connor, Chief Justice William Rehnquist was not happy. He reviewed the history of the flag and then admonished his brethren for concluding the majority opinion with “a regrettably patronizing civics lecture.” “Surely one of the high purposes of a democratic society,” argued Rehnquist, “is to legislate against conduct that is regarded as evil and profoundly offensive to the majority of people— whether it be murder, embezzlement, pollution, or flag burning.”

The Court’s decision was met with what Newsweek called “stunned outrage.” The Senate, in a 97–3 resolution, expressed “profound disappointment” with the decision. The House, in a 411–5 vote, expressed “profound concern.” Politicians scrambled to outdo one another in denouncing flag burning and the Court’s decision. One Republican congressman proclaimed that “probably no Supreme Court decision in our history since the infamous Dred Scott decision of 1857 has elicited such a spontaneous outburst of rage, anger and sadness on the part of the American people.” Congress quickly passed a new Flag Protection Act, but the Supreme Court struck it down. Long before that decision, President George H. W. Bush, standing before the Iwo Jima Memorial, called for a constitutional amendment banning flag desecration, and polls showed that most Americans supported him.

In 1989, a Senate vote on a constitutional amendment (“The Congress and the States shall have the power to prohibit the physical desecration of the flag of the United States”) fell short by fifteen votes of the two-thirds majority needed. The amendment returned again in 1995 and has been passed by the House and rejected by the Senate in every Congress since (though in 2006 it failed by only one vote in the Senate). It was easy to mock the absurdity of the amendment, and an essayist at Time spoke for most pundits when he wondered, “If there is only one official U.S. flag, would it be permissible to burn an unofficial one—say, an obsolete model with 48 stars? . . . What about little lapel pins or cuff links with flags on them? What if somebody publicly stomped a piece of such jewelry? . . . Should a law protecting the flag also protect homemade facsimiles of the flag? Is a crayon drawing of the flag a flag? Besides burning, what would constitute the ‘physical’ desecration some of our political leaders emphasize they hope to outlaw? Does that include obscenely wagging a finger at a flag? Sticking out one’s tongue at the flag? Thumbing a nose at the flag? What if some miscreant mooned the flag? Or stuck pins in the flag—in public?” However inventive the scenarios imagined by commentators (electrocuting someone who had a flag tattoo), their point about the ambiguity of the amendment, not to mention its collision with the First Amendment, might be well taken by liberals, but the rising tide of moral conservatives in America meant that most politicians feared opposing the amendment and being branded as unpatriotic.

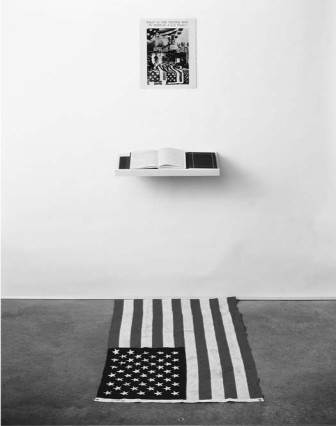

Controversies over depiction of the flag in art further fueled the cries for a constitutional amendment and help account for the return of the amendment in 1995. In 1989, a conceptual artist, Dread Scott, displayed his work What Is the Proper Way to Display a U.S. Flag? at an exhibition at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Scott, raised in Chicago’s Hyde Park, describes himself as making “revolutionary art to propel history forward.” What Is the Proper Way consists of several parts: a mounted photograph that has the title of the work and shows a collage of flag-draped coffins and South Korean students burning the American flag and holding signs (YANKEE GO HOME SON OF BITCH), a mounted shelf below the photograph with a blank book and pen, and a 3'×5' flag spread on the ground. Viewers were encouraged to write comments in the book, which would require them to stand on the flag as they did so. One writer said Scott should be shot; one wrote, “Let it burn”; one denounced the flag as a racist symbol of an oppressive regime; another called Scott an “asshole”; and one entry thanked the artist: “It does hurt me to see the flag on the ground being stepped on. Yet now after days have passed, I have realized that this is the ultimate form of patriotism. Our country is so strong in believing what it stands for that we would allow you to do this. You have made me really think about my own patriotism, which has grown stronger.”

Dread Scott, What Is the Proper Way to Display a U.S. Flag?, 1989 (COURTESY DREAD SCOTT)

The installation elicited a storm of protest. Veterans’ groups marched outside, and when they entered the exhibition they picked the flag up off the floor, only to have the guards restore it to its intended position. Police threatened to arrest anyone who stood on the flag. The gallery received bomb threats, and Scott received death threats. Politicians tried everything to close down the exhibition. A lawsuit failed when a judge ruled that “this exhibition is as much an invitation to think about the flag as it is an invitation to step on it.” President Bush called the work “disgraceful,” and the debate over passage of the Flag Protection Act included references to “the so-called ‘artist’ who has invited trampling on the flag.”

In 1994, Scott’s piece was one of dozens, along with works by Jasper Johns, Kate Millett, Robert Mapplethorpe, Faith Ringgold, and many others, featured in an exhibition titled “Old Glory: The American Flag in Contemporary Art.” Inspired in part by the 1989 debate over flag desecration, curator David Rubin surveyed artistic representations of the flag primarily from the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. In Cleveland, where the exhibit opened, “Old Glory” received critical reviews, and when the show moved to Arizona in 1996, once again it was met with protest. Veterans repeatedly grabbed the flag out of the toilet in Kate Millett’s piece and off of the floor in Scott’s, and they marched outside in opposition. Politicians denounced the show and threatened to cut off all funding to the Phoenix Art Museum. Although in the second half of the twentieth century artists and the culture at large had desacralized the flag as a symbol of patriotism and nationalism, representations of Old Glory continued to evoke powerful emotions. The idea of disrespecting the flag, especially to cultural conservatives and military veterans, seemed treasonous. At the same time, many Americans wondered whether they were included in the social compact signified by Old Glory, and whether they could continue unequivocally to support the direction of the country. Patriotism in the late 1980s and the 1990s became the focus of a symbolic politics that seemed to eschew tackling deeper issues of economic disparity and social injustice. Americans had always enlisted the flag to give legitimacy to their cause, to claim membership in the nation, but now all too often they were being asked to “rally around the flag” (a phrase first sung during the Civil War) simply for the flag’s sake.

And then came 9/11. In the outpouring of national feeling after the terrorist attack, flags were everywhere, waved by everyone. Even those who disdained the flag took newspaper reproductions and taped them to their windows. One writer spoke for many when he said, “I love Old Glory. I just wonder if I can take it back from the creeps who’ve waved it all my life.” Writing in Salon on September 18, 2001, King Kaufman captured the tension: “For most of my life, the American flag has been the cultural property of people I can’t stand: right-wingers, jingoists, know-nothing zealots. It’s something that hypocritical politicians wrap themselves in. It’s something that certain legislators would make it a crime to burn—a position that’s an assault on the very freedom that the flag represents . . . But I also love the flag. Seeing it stirs something in me, even when I’m mad at it, or disagree with those who wave it. I am, after all, an American, and despite being opposed to every single military adventure this nation has undertaken in my lifetime, I’m a patriotic one at that.”

Michael Moore, a documentary filmmaker who often clashed with conservatives, agreed. “For too long now,” he argued, “we have abandoned our flag to those who see it as a symbol of war and dominance, as a way to crush dissent at home . . . Those who absconded with our flag now use it as a weapon against those who question America’s course. They remind me of that famous 1976 photo of an anti-busing demonstrator in Boston thrusting a large American flag on a pole into the stomach of the first black man he encountered. These so-called patriots hold the flag tightly in their grip and, in a threatening pose, demand that no one ask questions . . . I think it’s time for those of us who love this country—and everything it should stand for—to reclaim our flag from those who would use it to crush rights and freedoms, both here at home and overseas.”

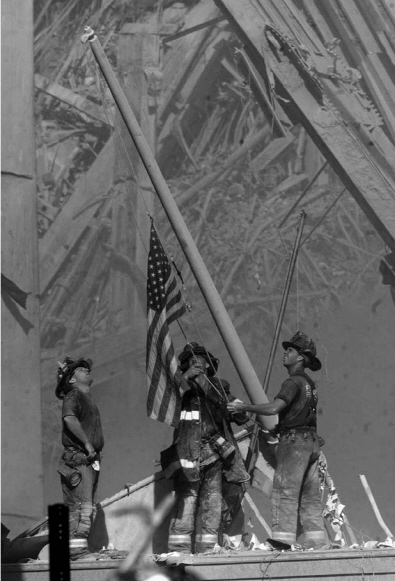

Moore was writing in 2004, in opposition to the Patriot Act, which gave the federal government unprecedented powers to infringe on civil liberties in the interest of national security. By then, a photograph taken on 9/11 had given new life to Old Glory. Thomas Franklin, of the Bergen Record, spent most of that day at the riverfront by Jersey City, shooting pictures of the smoldering buildings before their collapse and of survivors as they got off the tugboats carrying them to safety from lower Manhattan. Police kept stopping him, even threatening to arrest him, but he kept going. At some point, he was pushed and his camera slammed into a light pole. The camera jammed, and he lost all the pictures he shot that morning.

In late afternoon, he managed to hitch a ride across the Hudson. At the scene, he worked his way toward ground zero. He did not even know if his camera was functioning correctly, but he kept on taking pictures. Late in the afternoon, he was standing beneath what had been an elevated walkway and saw the firefighters off in the distance preparing to raise the flag. He was more than 150 yards away, shooting with a long lens that collapsed the distance between the men and the rubble behind them. He took twenty-three shots and then, nervous about losing the image, removed the photo card from his digital camera and placed it in his pocket. From a hotel, he transmitted two pictures to his office. The photograph, the fourteenth shot of the sequence, taken at 5:01 P.M., appeared on the front page of the Bergen Record the next day, and soon was seen around the world.

Old Glory Raised at New York’s World Trade Center is what some called the photo. Franklin calls it Flag Raising at Ground Zero. The photograph redeemed the flag from the ambiguity of the previous decades and restored to it a luster not envisioned since Joe Rosenthal’s photograph. Franklin immediately made the connection: “As soon as I shot it,” he said, “I realized the similarity to the famous image of Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima.” Franklin’s photo is monumental, a study in contrasts. The red, white, and blue puncture the sea of gray destruction; the firefighters’ delicate hands are set against sharp, twisted steel; the eyes look up at a moment when all has come crashing down. There is a religious sensibility to the image, the twisted steel seeming to form a cathedral and suggesting the shape of a cross. One can tell a compelling story about America from the three great news photographs that feature Old Glory: Joe Rosenthal’s, Stanley Forman’s, and Tom Franklin’s. The story would be about triumphant nationalism in World War II, deep-rooted hatred at the time of the Bicentennial, and stubborn courage in the face of catastrophe in the new millennium.

Tom Franklin, Flag Raising at Ground Zero, 2001 (COURTESY TOM FRANKLIN AND THE BERGEN RECORD )

Eric Gay, Milvertha Hendricks, 2005 (ASSOCIATED PRESS)

Or consider a different story suggested by a different sequence of images: James Karales’s photograph of a civil rights protester in 1965, Stanley’s Forman’s picture, and an image taken by Eric Gay on September 1, 2005. Gay made it to the French Quarter in New Orleans just as Hurricane Katrina reached Category 5. Thousands of residents, mainly black, could not evacuate, and they congregated at the Convention Center. There was no food or water or electricity or emergency service, but they kept coming because they had nowhere else to go, and help, days after the storm hit, still had not arrived. Milvertha Hendricks, age eighty-four, was one of hundreds who sat outside in the rain. In Gay’s photograph, the American flag provides her only shelter. She stares ahead, but there is no life in her eyes. Her brow is furrowed; her lips are pressed tightly together. The fingers of her right hand dangle beneath a red stripe of the flag, which reaches back to cover a few others. The flag is her mourning shawl. Whatever promises had been made to her by the civil rights movement of the 1960s had been broken.

On 9/11, Stanley Forman jumped into his van and headed toward New York. In doing so, he was following the instinct of every photojournalist within driving distance. He had his cameras loaded and ready, but before he traveled very far down Interstate 95, he got a call to turn around and head to Logan Airport. Information was coming in that one or two of the hijacked planes originated in Boston, and his editors sent him to Logan to cover the story. He got the only images of the car the hijackers used, and of seats being taken off of a connecting flight for investigation. But not being able to get to New York, for what one writer has called “the most widely observed and photographed breaking news event in human history,” broke his heart.

Covering the story at Logan Airport meant shooting moving images. In 1983, Forman left still photography for videography when he joined WCVB in Boston. The previous year the Hearst Corporation had sold the Herald American to Rupert Murdoch, and the paper became a tabloid, the Boston Herald. Forman decided it was time for a change. He’d had a chance a few years earlier, after winning his second Pulitzer, to move to the New York Times. After all, he was one of the premier photojournalists in the country, so much so that Nikon took out an ad in News Photographer in 1978 that showed his work and read, “Right now Stan Forman is cruising the streets of Boston waiting for his radio to crackle into life. The next call could send him and his Nikon cameras off to win a third Pulitzer Prize.” (The staff photographers of the Herald American won the Pulitzer Prize in 1979 for coverage of the blizzard of 1978. Technically, Forman had won a third Pulitzer, though he does not count it because he was laid up with a broken leg.)

When the New York Times called, he went down for an interview. He had a nice lunch at Toots Shor’s and enjoyed his visit, but he never really considered making the change. An item in the gossip pages suggesting that the Times was wooing him earned Forman a raise, and he stayed at the Herald American. He has no regrets. The Times was not for him, and the self-described “home boy” was not about to leave Boston.

The switch to video excited him. At age thirty-eight, Forman took it as a challenge and felt revitalized by the move. He also did not think of the shift from still to moving images as all that remarkable. “It was the same job with a different tool,” he says. Besides, he had no delusions about his gifts. He had been “another mediocre photographer that made a great picture and suddenly became non-mediocre.” Time and again Forman has said he is not a real photographer and uses Eddie Adams, the Vietnam War photojournalist, as a comparison. One time he was on a trip with Adams and other photographers. Everyone took a shot of a guy diving off a boat. Adams’s vision stood out—his picture was at an angle, whereas Forman’s was straight down. Adams could “see” in a certain way that Forman feels he could not. Maybe the difference was between news photography and photojournalism, a term Forman does not use. “I shoot news,” he declares. “If it is moving I’m going to get it.”

If Forman is too self-effacing (in 1980 he received the highest award given by the National Press Photographers Association, the Joseph A. Sprague Memorial Award, an award also won by Eddie Adams), his modesty is also the key that keeps him going. “Every day I get up I have to prove myself,” he admits. He loves the competition of getting to the scene first, or grabbing an exclusive, or just having better stuff than anyone else. Almost the only regret he had about leaving still photography was that he would no longer get the regular thrill of seeing his name in print. “There’s still nothing like your name under the photo on page one of the paper,” he said in 1992. “It’s a wonderful feeling. It gives you a smile.”

But the new job had plenty to offer, especially financial security. He tells a story about his first day at Channel 5, a story that helps quell any uncertainties he may have had about leaving one camera for another. There was a building collapse in Chinatown, on a rainy day. Forman was being trained in the use of the new equipment, and his supervisor had him holding an umbrella over the camera as they made their way to the scene. Forman ran into the assignment editor from the Herald, who joked, “So, Stanley, this is the new job.” “Fifty thousand dollars a year to carry an umbrella,” Forman quipped. “Any more openings?” responded the Herald photographer.

Forman has been a television news photographer longer than he was a still photographer, and although he has won numerous awards from the Boston Press Photographers Association for his work (five times for still photography, tying the record of his idol Rollie Oxton, and five times for videography), he talks about the difficulties of the video form. To begin with, the camera weighs twenty-two pounds, and by day’s end it feels like fifty. In his early sixties, with a bad back, Forman no longer runs to get to a story. Besides, he learned long ago that it is not always the first at the scene who gets the best shots.

It took him time to adjust to the additional demands of video. For example, now he had to think in terms not only of picture but also of sound. The job also required working more closely with reporters than he had as a still photographer. There were more scenes to think about, making sure he gave the editor enough footage to work with to tell a story. And the nature of what he had always considered news was different. For television, you could shoot a first-day story on the second or third day, catching up to what others had. With stills, either you got the news-making shot or you did not.

He also realizes that video does not have the impact of stills. To be sure, there are exceptions, such as the video of the Rodney King beating or footage from 9/11, but video is evanescent. It tends to lessen the dramatic impact, whereas stills isolate and augment it, perhaps even create it. Such is the case in comparing Joe Rosenthal’s still shot with moving pictures from the flag raising at Iwo Jima. The lesson is equally clear with the assault on Landsmark. The newsreel shot by cameramen rolls by in seconds. We are shocked by the brutality of the punches and kicks, and Landsmark falling to the ground. Rakes dashes in with the flag, swings and misses, and then it is over. No isolated moment to study. No fixed image to lay claim to our souls. The video has literally faded with time. “Stills,” Forman knows, “last forever.”

At times, Forman has brought his still camera to the scene and joined the two sides of his photographic eye. In 1986, he came across a burning house while cruising late at night. His sequence of rescuers dropping a baby from a burning building, and other victims jumping from the roof as flames shot up into the night sky, got him the first page on many national newspapers, including the Globe. His award-winning video work includes a drowning in Lowell, a Goodyear blimp caught in the trees in Manchester (he was the only one to get through police lines and into the woods), and even a flag burning at the Democratic National Convention.

What Forman possesses that few photographers twenty years his junior have is an uncompromising work ethic. “Luck is the residue of hard work” is one of his favorite phrases. Clearly, preparation is a key to his success. “Some people learn a new word every day,” he says. “I try to learn a new street. It’s important in this job. I look at a street and think, hey, I might have to come here someday. Where is it? Is it one way? Does it dead-end? Where are the stoplights?”

Although he now has GPS, he seldom uses it. But he has scanners and pagers and radios buzzing at all times. Both his van and his house are repositories of beeping, crackling, blaring sounds. In the middle of the night his wife turns up the air-conditioning so she does not have to listen. And he turns up the volume. There’s a practical side to all this: he goes out at all hours, shoots a fire or an accident or a rescue, transmits the footage from his van, goes back to bed, and earns four hours overtime. Most of the time, his wife does not even know he’s gone.

As necessary as the money is, that is not what drives him. He has never lost his childhood love of the chase, of hearing sirens and standing in the swirl of action. It may be that news is now entertainment and presentation, rather than content, but Forman shuns no assignment and loves it every time his work gets on the air. That part never gets old. He continues to carry a digital still camera in each of his cars. He sometimes allows himself to dream about getting one more great shot, one more big one, not for him but for his daughters, who were born long after he first gained an international reputation for his work.

For more than forty years, Forman has worked in Boston, and he has friendships with seemingly everyone in and around town— firefighters, cops, paramedics, politicians, businessmen, journalists. In November 2006, Forman was in South Boston to cover the dedication of a playground at St. Peter Academy to Jim Kelly. Kelly spotted Forman and warmly said, “How’s my friend Stan?” Politicians, students, teachers, and constituents crowded the playground for the ceremony. The mayor said, “Politics is still about people, and no one personifies the people business better than Jim Kelly.” A state representative said Kelly was a fighter who “never took a step back.” Suffering from cancer, Kelly managed to offer his appreciation and smiled as the children sang “God Bless America.”

Kelly’s visibility and relentless advocacy through the busing crisis of the 1970s brought him the devotion of South Boston residents. He was arrested numerous times for civil disobedience. Kelly was so tough that once, while he was being arrested, cops pulled at the hair on his chest and he did not flinch. He despised busing and says it was not “a black and white situation” but about fairness, and legality, and cost. Asked about Forman’s photograph, he says the incident was a “mild skirmish,” and it was the image that made it seem like something more. He concedes, however, that it did damage the anti-busing cause.

In the aftermath of the busing crisis, Kelly moved formally into politics and competed for City Council in 1981, running a grassroots campaign by knocking on doors and emphasizing “neighborhood stability.” Though he lost narrowly, he won the support of labor unions and the police. Two years later, he was elected to the City Council. He remained there, serving as council president from 1994 to 2000. Kelly represented District 2, which consists primarily of South Boston, the South End, and Chinatown.

Within a handful of years after his election, Kelly was at the head of another controversy over race: discrimination in public housing. The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development found that the Boston Housing Authority had discriminated against blacks in assignments to public housing projects in South Boston and ordered the wrong rectified by freezing the waiting list until minority families had received apartments. To Kelly, this smacked of unfairness, and once again his populist rhetoric came to the forefront as he talked about “forced housing” versus “freedom of choice.” Accused of being racist, Kelly dismissed the charge by saying, “I am outraged by any policy that gives preference at the expense of another because of race.”

Kelly’s neighborhood approach may have veiled his hostility to outsiders, and the unintended consequences of his rhetoric undoubtedly perpetuated racial division and hatred. By the 1980s, however, he was not the kind of activist he had been a decade earlier. In 1988, the Globe described him as a “voice of restraint in a segment of the community that is again rattling sabers, feeling betrayed and singled out for social experimentation.” Kelly would work for what he believed in through the courts, through politics, and through reasoned debate that took place, preferably, away from the media. “I will not pander to the press,” he said repeatedly. When the first black families moved into South Boston’s McCormack housing project, Kelly stayed away. “I don’t go and introduce myself and welcome every white family that moves in either,” he said. But he also “took it as a personal responsibility,” he promised, “to make sure that no black families felt threatened and that no South Boston kids were arrested for civil rights violations.”

In the 1990s, Kelly opposed any affirmative action plans for hiring. Again, he expressed his central concern in terms of fairness, the major chord of his political philosophy. In a forum on race with President Bill Clinton, Kelly said he understood that one of the legacies of slavery was black poverty, but there were many poor whites as well, and the only question that mattered was whether they were “fit and willing and qualified.” Kelly called for hearings at the City Council and said, “There is a lot of unfair treatment to people who take the test [for city employment], pass it, but because of their race they are being denied the opportunity.” In a liberal city, Kelly was accused of divisiveness, but his conservative position (he described himself as “a union-oriented Reagan Democrat”) was fueled less by racism than by the only desire that governed his political career: supporting the sanctity of neighborhoods and the needs of his constituents. To anyone listening carefully, Kelly said as much when, in talking about majority-black districts, he acknowledged that “if I was the district councilor from Mattapan, I’d probably agree that racial set-asides are a necessity.” One supporter from the South End said, “He’s constituent-oriented. He doesn’t care what the color of your skin is, what your personal beliefs are, what nationality you belong to.”

Though one might not glean it from his positions on housing discrimination and affirmative action, Kelly’s racial attitudes had changed. If in the seventies he was heard to yell racial epithets, he now defended equal rights and treatment. He helped work on a human rights ordinance and made it clear, according to one councilor, “that he is opposed to any people being victims of violence or discrimination.” At the same time, he supported everyone’s right to associate with whomever they pleased. Asked about racism in 1988, he told the Herald, “If you define racism as someone who willfully denies people of the opposite race their rights, someone with a hatred of other races, no I’m not . . . It suits the liberals’ purposes,” he argued, “to paint everyone who opposed forced busing as a racist.” In 1994, Kelly said, “I don’t think someone is a racist simply because they’re more comfortable with associating with their own people with whom they have much in common . . . Do I want to see blacks get good decent jobs and to live in good, safe neighborhoods and go to school and get a good education? I want all those things for blacks, Hispanics, Asians as much as I want them for people in my own neighborhood.” But that did not mean he wanted his daughter to marry a black man or a foreigner, he said. If Kelly’s honesty made the liberals squirm, so be it.

For Kelly, the neighborhood was everything. Much of his social and political philosophy through the 1980s and ’90s was governed by an almost nostalgic desire to preserve a South Boston that, in reality, no longer existed. “I just don’t see why the neighborhood has to change,” he lamented in 1993. “I don’t see why it has to be any different than when I was growing up there.” But even as he spoke, South Boston, like the city at large, was being transformed. A study conducted in 1999 found that 37 percent of South Boston residents entered the city after 1990, and a total of 48 percent of the people in the community were not born or raised there. The central reference point of Kelly’s career, the busing crisis of the 1970s, had no meaning to these newcomers.

Described time and again as the council’s “hardest-working member” and as someone who consistently delivered services to his constituents, Kelly relentlessly (some might say ruthlessly) defended his district. He battled with the mayor and the Boston Redevelopment Authority over development of the seaport, wanting the area to be known as the South Boston Seaport, opposing the building of new housing that would gentrify the area, and creating the controversial South Boston Betterment Trust, which negotiated and received payments from developers for commercial projects.

Kelly’s district is currently about 66 percent white, 8 percent black, 10 percent Hispanic, and 15 percent Asian. A devout Irish Catholic, he remained a steadfast social conservative (he opposed the Supreme Judicial Court’s ruling allowing for gay marriage in Massachusetts). But he worked tirelessly for his constituents, regardless of their race, occupation, or ideology. Ill with cancer, Kelly still made time every week to respond to the voters. His beloved South Boston was not his childhood neighborhood any longer, but he steadfastly fought for it until he passed away at age sixty-six on January 9, 2007. One African American politician summed up his years of service this way: “regardless of how you might feel about his stands, he’s absolutely been an institution and a beloved public servant to the people of South Boston.”

In the late 1980s, Landsmark bumped into Kelly around City Hall. He had heard that Kelly was in Forman’s photograph, and he asked him about it. Kelly smiled enigmatically and didn’t answer. But in the years after that he always called Landsmark “Teddy” and treated him as one of the inner circle.

Ted Landsmark had also found his way into politics, though he never ran for elective office. In 1988, Mayor Ray Flynn appointed Landsmark director of the Mayor’s Office of Jobs and Community Services and, a year or two later, director of the Safe Neighborhoods Project. Since his election as mayor in 1984, Flynn had worked to heal the racial fissures opened by the busing crisis. Appointing prominent black and Latino leaders to positions in city government was one of his ways of reaching out. Landsmark’s office was responsible for fighting poverty and providing job training. His work as a dean had been satisfying, and Landsmark did much to promote multicultural education and affirmative action policies. But Landsmark decided to join Flynn after listening in horror as his former boss Michael Dukakis mishandled a question on rape in a presidential debate, an issue with racial overtones because the Republicans had politicized Dukakis’s decision as governor to furlough a black inmate who had been convicted of sexual assault. Landsmark felt a responsibility “to get my hands dirty again” and to get involved in “the public sector where my day-to-day actions will have an immediate impact.”

Landsmark did an outstanding job in the mayor’s office. He helped organize forums, provided youths with summer jobs, created local networks, and coordinated community-based health activities. His understanding of the importance of community action and involvement was central to his success. One could not simply wait for the police to stop crime; with his leadership, activists and parents worked with police authorities to fight it. He also provided grants to other groups, such as Gang Peace, which sought to help youths turn negative relationships into positive ones. The efforts contributed to a dramatic decline in the homicide rate in Boston, by 25 percent citywide and 53 percent in Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan.

Mayor Flynn also took quick action to try to curtail racial violence. When a black South Boston public housing resident was beaten with a baseball bat, Flynn revived a Civil Rights Cabinet and placed Landsmark in charge. The group, consisting of high officials from various city agencies and departments, met monthly and sought to mobilize, in Landsmark’s words, “a broad spectrum of community support for the basic human and civil rights of all our citizens.” Landsmark also organized interdenominational services of peace and healing in South Boston and Charlestown.

The most inflammatory racial event since busing to erupt in Boston occurred in October 1989 when Charles Stuart reported that his pregnant wife was killed and he was shot in the stomach by a black assailant in the Mission Hill district, an integrated neighborhood. Police aggressively pursued various suspects and made an arrest. But Stuart’s brother told police that it was Charles who killed his wife and wounded himself. The case ended on January 4, 1990, when Stuart committed suicide. The racial reverberations would have lasted longer but for Flynn’s understanding that his office had to respond forcefully to the racial profiling that had taken place. He had Landsmark study the way the media overplayed the racial aspects of the case and cast Mission Hill in an unfavorable light. Flynn sought a rational and coordinated approach to the portrayal of the city and addressed specific substantive neighborhood needs such as economic development and youth services. In the end, says Landsmark, “a deranged and suicidal individual was using race for his own selfish purposes.” With his advice, Flynn was able to defuse the situation, ease tensions in Mission Hill, and explain how “it turned out we were all victims of a sinister hoax.”

Landsmark’s only misstep, it seems, came the first time he addressed an issue directly related to public education. Comments he made off the record in 1993 about METCO, the voluntary busing program started in 1966 that sent inner-city children to suburban schools, drew him close to the third rail of Boston politics. Landsmark suggested phasing out METCO so that the Boston public schools could reap the benefit of the thirty-five hundred students not in the system. “We cannot hope to improve the quality of our neighborhood schools,” Landsmark said, “without the participation of active parents whose upwardly mobile aspirations for their children are an essential ingredient in an improved learning environment.” METCO supporters denounced Landsmark and proclaimed that his comments were an insult to the students and parents in Boston’s public schools. They called him “a lazy bureaucrat” and accused him of looking for “scapegoats.” Landsmark was not politically naive, but still the reaction took him by surprise. Even the black community ostracized him. He merely thought that the energy and ambition of those parents whose students travel to the suburbs every day would have an impact if employed in neighborhood public schools. He recalled that he too had been bused, but one of the consequences was feeling detached from where he lived as well as where he went to school. The controversy passed, and it would be a while before Landsmark would again comment on Boston’s public schools.

The following year, when he was working as an aide to newly elected Mayor Thomas Menino, Landsmark looked up as his office door opened. In wandered a man filled with sorrow and in search of forgiveness. Bobby Powers, one of Landsmark’s attackers nearly twenty years earlier, introduced himself. “It is with great humility that I approach you and tell you that I was the individual who initiated the attack on you,” Powers said. Landsmark heard Powers’s confession, and the two talked for an hour. Powers told a Boston Herald reporter, “I always blamed busing for a lot of my problems. But a lot of my problems were with myself.” After 1976, Powers faced various legal problems and fell into alcoholism. He realized he could never move forward without confronting what he had done. “I was not a racist,” Powers said. “I was just an angry young man, a boy really . . . I wanted to make amends, I’m not a hateful person.” Powers now had a son, and he wanted desperately to break the cycle of hatred that twisted his life. So Powers asked Landsmark for forgiveness, but Ted told him he had forgiven his attackers long ago. Indeed, he said, “I always identified with the young men who attacked me. I’ve never forgotten that I grew up in public housing projects in East Harlem.” He added, “I’ve gotten beyond that experience. It happened so long ago that it feels like it happened to a different person.”

By 1997, Landsmark had left the mayor’s office to become president of the Boston Architectural Center, where he has remained since then. Now the Boston Architectural College, the BAC offers degrees in architecture, landscape, and design. Founded as a club for architects in 1889, the BAC has emerged as a central institution for degree programs, continuing education, and professional development in the field of architecture and design. Becoming president of the BAC fulfilled for Landsmark a lifelong quest: “I first dreamed of being an architect when I was a small black kid growing up with my mother in Harlem’s public housing projects.” Landsmark had shied away from becoming a practicing architect because of the isolation that he feared would engulf him as a black man in an overwhelmingly white profession. Now, as president, he could not only pursue his interest in shaping the built environment but also work on the issue of diversity in what he called “the most recalcitrant of professions.”

In 2002, Landsmark became chair of the American Institute of Architects Diversity Committee. He has insisted on better demographic analysis so the profession can track exactly who its members are, helped create mentoring and internship programs, investigated shorter routes to liscensure, and called for transformation in the studio culture of a profession that can be extremely difficult on women and minorities. Bringing together thirty years of experience as a lawyer, policymaker, civil rights activist, and educator, Landsmark has cogently made the case for why difference matters: “We must recognize that diversity and inclusiveness bring out not only different people, but different ways of thinking. Instead of feeling threatened by ideas that don’t simply reflect the thoughts and ideas we already have, we should celebrate our differences, and learn to love the richness that diversity brings. We are better design professionals and better citizens when we open our minds and hearts to different ways of thinking.”

At the time Landsmark became president of BAC, he was also engaged in graduate studies to deepen his understanding of African American culture. In 1999, he received a doctoral degree in American Studies from Boston University for his study of nineteenth-century African American crafts. Landsmark examined the work of black artisans, both slave and free, and discussed the challenges of collecting, exhibiting, and interpreting vernacular crafts. In a lecture on “Race and Place,” delivered at the Boston Athenaeum in 2004, Landsmark drew on his expertise to discuss the markers of identity in American culture. He talked about the civic life of the city and displayed cultural artifacts from the past—including a wood plane made by a black artisan—as a point of entry for engaging those whose experiences are different. “We are living in a new city,” he declared, a city in which being black meant you were as likely to be African as American, from Senegal or Nigeria as from South Carolina or Georgia. The new racial and ethnic diversity of Boston, he continued, meant finding ways to bring those who were part of a “marginalized social class” into full participation in Boston.

Landsmark also used the occasion to discuss a task force he was chairing at the request of the mayor. Its mandate was to gather public input on creating a new system for student assignment to Boston’s public schools. For all the work that Landsmark had done under two mayors, he had never before been directly involved in educational policy. But, in another sense, since everyone knew him as the man at the center of Forman’s photograph, he was seen as having always been at the center of the battle over busing. In choosing Landsmark, Menino sent a signal that whatever new policies emerged, they would not mark a return to the racial divisiveness of the 1970s.

In accepting the position, Landsmark noted that “life is full of ironic opportunities.” The risk of chairing the task force meant inviting countless questions about the photograph, something Landsmark preferred not to talk about. “My life has been a lot more interesting than the twenty-second moment captured in that picture,” he says. For years he did not own a copy of the picture, but he recently acquired a print, framed it, and placed it on the wall by his desk. An avid collector of art, he has in his office another recent purchase: the 1856 lithograph that depicts Crispus Attucks at the center of the Boston Massacre.

In taking on leadership of the task force, Landsmark was doing what he had done for nearly thirty years, serving the city he cherishes and helping find ways for it to move to a brighter future. If that also meant transcending in the public eye his place in Forman’s photograph, so much the better.

The school assignment system that Landsmark and his colleagues investigated no longer included race as a factor. In 1999, twenty-five years after the court decision that compelled Boston to desegregate its schools, the Boston School Committee, no longer elected but now appointed by the mayor, voted 5–to drop race in placing students. Facing a lawsuit that argued the system discriminated against whites, and reading a national legal landscape in which the courts were overturning affirmative action plans, Boston chose to seek other ways to balance school choice and class diversity. Besides, the demographics of the city had changed dramatically, with public school enrollment 49 percent black, 26 percent Hispanic, 15 percent white, and 9 percent Asian. The controlled choice system adopted in 1989, in which the city was divided into three zones and a variety of factors—proximity, race, lottery, family preference— determined what school a student attended, would continue, but with racial preference eliminated.

Skeptics saw Landsmark as providing political cover for a mayor who had already decided that busing was costing the city too much (some fifty-nine million dollars a year) and that a return to neighborhood schools might work. But Landsmark was no one’s shill, and he approached a series of open town meetings across the city with the goal of understanding what it was that parents wanted for their children’s education. He discovered a complexity that belied stereotype: “We’ve heard from some African-American and Latino parents in Roxbury who would like to have their children attend schools closer to home, and we’ve heard from some white parents in West Roxbury who would like the system to maintain some form of choice.” Preconceptions would have predicted the reverse.

Landsmark found that the policymakers had never really sought to understand what the parents wanted out of their schools. Above all else, parents wanted excellence. They desired a quality education for their children, and they demanded access. They wanted openness in decision-making, and they especially wanted to be treated with respect by school authorities. They desired diversity, but they wanted it along with high expectations for educational achievement. Most striking of all, he found that the issue that seemed most salient for the politicians meant next to nothing to their constituents: the past.

The demographic reality of Boston in 2004 was that it was peopled by residents who had not lived in Boston in the 1970s— indeed, who had not been born until after the crisis of busing had subsided. According to one estimate, some 80 percent of Boston’s black population did not reside in Boston at the time of the busing crisis. “The number of people who carry the baggage of Boston’s racism is very few,” observes Landsmark. That was not to say that they had not experienced their own incidents of racial prejudice and ostracism. But it meant that they were not burdened by the weight of having experienced the busing crisis firsthand. “You might as well be talking to them about Lincoln freeing the slaves,” Landsmark emphasizes, “as talk to them about busing and how it tore neighborhoods apart.”

It is a striking observation, and it gets to the essence of one of the ways reputations change: the passage of time. A writer once commented that “history democratizes our sensibilities.” He meant that as time goes by we forget the details, we lose our sense of absolute right and wrong, we forgive the dead. And while those who battled against one another in the 1970s over the issue of busing are not about to join together on a nostalgic walk across City Hall Plaza, the survivors—most of them, anyhow—have obtained some peace. For everyone else, it is a history with which they are not personally saddled.

If the crisis of busing has slipped into long-ago history, it has also been submerged by a reversal in attitudes toward desegregation. As many educators have shown, most notably Gary Orfield and his associates at the Civil Rights Project, the more than fifty years since Brown v. Board of Education have not been kind to the dream of integration. Indeed, there has been a massive resegregation of the schools throughout the nation over the past quarter century. This has occurred despite Orfield’s finding that “Americans of all races express a preference for integrated education and believe it is very important for their children to learn to understand and work with others of different racial and ethnic backgrounds.”

As a result of the actions of a conservative Supreme Court that has reversed itself on questions of desegregation and affirmative action programs, a failure of political leadership, profound demographic shifts in the makeup of cities, and the eventual loss of a social sense of urgency once dejure segregation had been eliminated, school resegregation and educational inequality have soared. Jonathan Kozol, who has devoted his career to promoting good learning in urban public schools, calls the problem “America’s educational apartheid,” a system where no one any longer speaks of racial segregation and instead uses “linguistic sweeteners, semantic somersaults, and surrogate vocabularies to talk around the problem.” Fifty years after Brown, still separate and still unequal is Kozol’s judgment on America’s schools.

That is not to say the 1954 decision was a failure. Legal, publicly funded discrimination had been eliminated. And some urban school districts have managed, despite the retreat from integration, to show impressive gains in student achievement, none more so than Boston’s, which in 2006 won the half-million-dollar Broad Prize for demonstrating “the greatest overall performance and improvement in student achievement while reducing achievement gaps for poor and minority students.” The struggle against segregation and racism, like the struggle for quality education, requires constant vigilance and generations of community leaders willing to reinvest old ideals with new currency.

Such is the case in Boston. If the city today is more cosmopolitan, sophisticated, diverse, and tolerant than it was three decades ago, it is that way because of the concerted effort of people like Landsmark. He had every reason to flee in 1976, and every reason to be angry and unforgiving, but instead he stayed and served with distinction. Asked if he thinks Boston is a racist city, he immediately answers no. The racial climate “is a completely different world” than it was in the 1970s. “The city has matured,” he says. “It is more accepting of difference.” To be sure, there has not yet been a black mayor (unlike in New York, Philadelphia, and Atlanta), and that would certainly help boost its reputation, but the city is no more racist than any other. Stanley Forman agrees: “I can’t believe it’s a racist city. I can’t believe it’s any different than any other city.” He says that Boston has succeeded in recent years in altering its image, an image fixed by his photograph.

In 2002, Boston magazine asked, “Is Boston Racist?” and found that while there was still significant residential segregation, Boston’s self-image was out of step with how the rest of the nation viewed the city. The magazine polled people living elsewhere and found that they overwhelmingly thought of the place as progressive. To change Boston’s reputation from within, a new generation of leaders have worked together to transform the feel and character of the city. They have increased minority voting, forged partnerships with businesses and cultural institutions, and created support networks for black professionals. Equally important, blacks in Boston have decided no longer to remain invisible in the civic and cultural life of the city.

That does not mean Forman’s photograph has vanished. Nearly every comment about the city’s progress mentions the picture. It is the reference point against which all change is measured. Boston magazine reminded readers that “because the busing era became so entrenched in people’s minds thanks to a photo of a white man attacking a black man with the pole of a big American flag, that past still clings to the city.” The photograph cannot be erased. But it can be engaged, and its meaning can be transformed.

The Soiling of Old Glory captures an instant of unthinkable racial hatred. The photograph would lead, at first, to turmoil and self-scrutiny, and later, to progress and healing. Some may have remained forever chilled by being caught in that frozen moment. But others could gaze beyond the frame. They had personal and professional work to do, work on behalf of a broken city that they loved.