The battle over busing did not begin in Boston. Years before violence erupted in 1974, other American cities struggled with busing: Pontiac, Providence, Trenton, Detroit, Denver, Pasadena. And, of course, before the crisis turned north, southern cities wrestled over busing as a means of desegregating public schools. The battle over busing did not begin in Boston, but it was in Boston that the issue exploded in such a way that the city came to be seen as the Little Rock of the North; some even compared it to Belfast. Those sobriquets did what all nicknames do: they simplified and stereotyped. Boston’s battle over busing took the shape that it did as a result of numerous competing and conflicting factors, and in the context of its own unique history.

In searching for the beginning of a story it is tempting to go back, far back, so far back that there is the danger of suffering from the disease that historian Garrett Mattingly diagnosed in his friend Bernard DeVoto: regressus historicus. It seems that DeVoto, the author of bestselling works on American history published in the 1940s and ’50s, could not write about nineteenth-century America without going back to the sixteenth century and crossing the Atlantic to England. While we can tell the busing story without leaving this continent, there is perhaps some justification in starting as far back as June 24, 1700, when a pamphlet condemning slavery and the slave trade was published in North America—printed in Boston.

Samuel Sewall’s The Selling of Joseph appeared at a moment when the Massachusetts slave population had recently doubled to more than five hundred slaves, most of them in Boston. Sewall, a jurist who had come to regret his role in the Salem witch trials in 1692, was compelled to reflect on the nature of slavery when he received a petition asking him to free “a Negro and his wife, who were unjustly held in Bondage.” In The Selling of Joseph, Sewall argued that “all men, as they are the Sons of Adam, are Coheirs; and have equal right unto liberty, and all other outward comforts of life.” Sewall could not possibly imagine free blacks living in equality and side by side with whites (“they . . . remain in our body politick as a kind of extravasat blood”), and his pamphlet had no discernible impact. But that a Boston man spoke to the problems of slavery and freedom foreshadowed how essential these issues would become in the city soon to be known as the Cradle of Liberty.

The relationship between the principles of the American Revolution and the problem of slavery has long vexed scholars. “All men are created equal” seems perfectly unambiguous, and yet the phrase certainly did not lead to any mass abolitionist movement. Indeed, for many there seemed to be almost an inverse relationship between the call for liberty and the reliance on slavery. The famed British writer Samuel Johnson seized on this anomaly and inquired, “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?”

In Massachusetts, as well as other northern states, the rhetoric of liberty fueled nascent anti-slavery sentiment among some politicians, and certainly among the enslaved. The Massachusetts Constitution of 1780, written by John Adams, includes a Declaration of Rights that says, “All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness.” Three years earlier, the Massachusetts General Court had received a petition from “A Great Number of Blackes detained in a State of slavery in the bowels of a free & Christian County,” who set out to show “that they have in Common with all other men a Natural and Unalienable Right to that freedom which the Grat [sic] Parent of the Universe Bestowed equally on all menkind and which they have Never forfeited by any Compact or agreement whatever.” By 1783, the Supreme Judicial Court had ruled in several cases that slavery was incompatible with the principles of the state constitution.

With the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts, a small but vibrant free black community began to emerge. In the early 1800s, about 1,500 blacks lived in the Beacon Hill area and parts of the West End and North End. The opening of the African Baptist Church and African Meeting House in 1806 established vital institutional structures for the growing black community that reached 2,200 (out of a population of 178,000) on the eve of the Civil War.

In antebellum America, Boston became a center of abolitionist fervor and the struggle for social reform. It was from Boston that David Walker, a free black printer and abolitionist, issued his Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World and William Lloyd Garrison, a writer, editor, and cofounder of the American Anti-Slavery Society, published the Liberator, a newspaper devoted to a doctrine that called for the immediate abolition of slavery. These activists were a decided minority, and their actions inflamed Boston’s merchants, who profited from trade with southern slaveholders, and outraged the rising number of Irish immigrants, who objected to being dominated by Protestant moralists. Garrison faced down mobs that dragged him through the streets with a noose around his neck.

Among the issues raised by black reformers was education. William Cooper Nell, who attended Boston’s Abiel Smith School, the first public school in the nation for black children, and became an apprentice printer for Garrison at the Liberator, petitioned the Massachusetts legislature in 1840 for school desegregation and equal rights, and he continued over the next decade to press for integration, “to hasten the day when the color of the skin would be no barrier to equal school rights.” The effort made some inroads with two members of the Boston School Committee, who published a minority report in favor of integration, but schools remained segregated.

In 1849, Benjamin Roberts, a black printer, challenged the law. His daughter, Sarah, had been denied admittance to four white schools—in violation, Roberts thought, of a statute that declared children could not be unlawfully excluded from the schools. The lawyers for Roberts were Charles Sumner, who would be elected to the Senate in 1851, and Robert Morris, the leading black attorney in the city, though he was only twenty-five. Before the Supreme Court of Massachusetts, Sumner argued that no “exclusion or discrimination founded on race or color can be consistent with Equal Rights . . . There is but one Public School in Massachusetts. This is the Common School equally free to all the inhabitants. There is nothing establishing an exclusive or separate school for any particular class, rich or poor, Catholic or Protestant, white or black.” In an argument one hundred years ahead of its time, Sumner insisted that there could be no such thing as equal but separate schools because “the matters taught in the two schools may be precisely the same; but a school exclusively devoted to one class, must differ essentially in spirit and character from that Common School known to the law, where all classes meet together in Equality. It is a mockery to call it an equivalent.”

Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw rejected Sumner’s argument: “The law has vested the power in the committee to regulate the system of distribution and classification; and when this power is reasonably exercised, without being abused or perverted by colorable pretences, the decision of the committee must be deemed conclusive. The committee, apparently upon great deliberation, have come to the conclusion, that the good of both classes of schools will be best promoted, by maintaining the separate primary schools for colored and for white children, and we can perceive no ground to doubt, that this is the honest result of their experience and judgment.” Prejudice, Shaw opined, is not created by the law, and it cannot be eradicated by it.

Shaw’s ruling in Roberts v. City of Boston would one day be taken as precedent for the “separate but equal” doctrine, but in Boston it would quickly be cast aside, as activists continued to challenge segregated schools. In 1855, with the support of the Committee on Public Instruction, the legislature passed, and the governor signed, a law that prohibited school segregation on grounds of race. A tradition of civil rights activism had been established.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Boston continued to grow. The population reached 250,000 by 1870. A terrible fire in 1872 destroyed some eight hundred buildings on sixty-five acres of land, but the city rebuilt itself. Roxbury had been annexed in 1868, and West Roxbury, Brighton, and Charlestown in 1874. With changes in the city came shifts in neighborhoods. The small black population began to move away from Beacon Hill and by the early twentieth century congregated in Roxbury, joining Jewish and Irish residents. Only in the 1950s, fueled by the migration north of southern blacks, did Roxbury become predominantly African American. Boston’s black population grew to 20,000 by 1930, 40,000 by 1950, and 63,000 by 1960, when African Americans reached a critical mass and constituted about 10 percent of the population. In 1970, there were more than 100,000 blacks out of a population of 640,000.

While Boston’s black population grew slowly over time, Irish immigrants poured into Boston in the 1840s and almost immediately constituted a third of Boston’s inhabitants. Settling in the North End and East Boston, these immigrants faced the prejudice of Boston’s Protestant elite, who feared the changes that engulfed them. By the end of the century, the Irish rose to respectability and seized political power. They also moved out of the waterfront slums into new areas, particularly Dorchester and Charlestown and South Boston, which had been annexed in 1804. South Boston became more than a residence; it became a neighborhood that provided a powerful sense of identity to a largely white, Irish, working-class, and Catholic population of about sixty thousand by the 1950s, proud of its heritage and bonds of intimacy. That sense of separation was reinforced geographically by the Fort Point Channel, which cuts South Boston off from the rest of the city.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, at the time of growing residential segregation, racial segregation in public facilities spread throughout the North. In 1896, Plessy v. Ferguson, the landmark Supreme Court case that upheld a Louisiana statute that provided for segregated public transportation, did not invent the doctrine of separate but equal; it ratified the reality of rising racism and social anxiety over the growing northern black population. In Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Illinois, Michigan, and Ohio, schools and facilities became more segregated. With the great migration of blacks out of the South following World War I, these cities became even more polarized racially, and school systems adopted even more exclusive practices.

The irony of Boston’s racial history is that relatively few blacks migrated to the city from the South, and, as a result, patterns of segregation did not become more rigid, and schools remained racially mixed. Boston’s seemingly benign situation in a comparatively progressive racial atmosphere had the effect of lessening the urgency of civil rights activism. Boston’s NAACP, which was integrated, collapsed by 1930, a victim of tensions with the national NAACP office, internal squabbles, and conflict with William Monroe Trotter’s National Equal Rights League, which spurned the paternalism of white civil rights leaders such as Oswald Garrison Villard, grandson of William Lloyd Garrison.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, Boston’s racial problems—in particular, employment discrimination that prevented blacks from getting jobs on the docks or in the trade shops, and kept them in menial positions as servants or porters—no doubt contributed to keeping down the number of blacks who migrated to the city from the South. Paradoxically, the small growth in the black population kept intact a generally liberal atmosphere about race and hampered the local agenda of civil rights activists. All of that began to change after 1940 as the black population swelled and came to constitute a meaningful percentage of the city’s total by 1960.

Symbolic of Boston’s racial polarization after World War II was an event that took place on April 16, 1945, at Fenway Park, home of the Boston Red Sox. That day, the Red Sox held a tryout for three black baseball players: Sam Jethroe, Marvin Williams, and Jackie Robinson. By an agreement among owners, no blacks had played on a major league team since the 1880s. But World War II had helped expose racial hypocrisy in the United States and led some to call for change. Boston city councilman Isadore Muchnick compelled the Red Sox to hold the tryout by threatening not to support the waiver needed to allow teams to play on Sundays. Still, the players got the runaround and waited in Boston for days to get on the field. Wendell Smith, a black sportswriter for the Pittsburgh Courier, wrote, “I have three of Crispus Attucks’ descendants with me,” a reference to the black seaman who was killed by British soldiers at the Boston Massacre: “They are Jackie Robinson, Sammy Jethroe and Marvin Williams. All three are baseball players, and they want to play in the major leagues . . . We came here to Boston—the cradle of democracy— to see if perchance a spark of the Spirit of ‘76’ still flickers in the hearts and minds of the owners of the Boston Red Sox and Boston Braves . . . We have been here nearly a week now, but all our appeals for fair consideration and opportunity have been in vain . . . But we are not giving up! We are Americans, the color of our skin to the contrary . . . and we are going to stick to our guns!”

The tryout lasted ninety minutes. The players left the field and never again heard from the Red Sox. As they walked off, someone from Red Sox management shouted, “Get those niggers off the field,” words that echoed in Boston for decades. The Red Sox would become the last team in major league baseball to include a black player—in 1959, twelve years after Jackie Robinson broke the color line with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. By then, a movement against segregation in all aspects of American life was well under way.

Northerners followed the southern resistance to desegregation with horror. The Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education that “separate but equal” is inherently unequal promised to erase decades of legalized segregation and launch nothing less than a civil rights revolution. The justices relied on the findings of psychologists and sociologists showing separate educational facilities to be detrimental to the development of black children. The Court did not impose a timetable except to say, the following year, that changes should proceed with “all deliberate speed.” In most communities, that meant no speed at all. The test of school desegregation came in 1957 at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. The nation watched as howling, hooting crowds mobbed the nine black children chosen to attend Central High, as the governor of Arkansas defied the Supreme Court, and as the National Guard had to be called in to take the children to school and try to protect them during the day.

In the 1940s and ’50s, many northern states had taken action to end explicit policies of school segregation. But only myopic northern liberals saw the problem of segregation as a southern problem. (There were plenty: on the day of the Brown decision one northern senator proclaimed that “the so-called ‘race problem’ is no problem at all for us.”) In fact, northern racial separation increased between 1945 and 1965. In Pittsburgh, for example, the percentage of black children enrolled in predominantly black secondary schools rose from 23 percent to 58 percent. Even more dramatic increases were registered in Chicago, Detroit, and Philadelphia. The main reason was increasing residential segregation. The combination of massive suburban migration after World War II and a system of policies and practices that sustained and reinforced racial separation and isolation (for example, racially restrictive covenants enforced by real estate agents and racial gerrymandering of districts) created de facto segregation in the North that was as insidious as anything known in the South. Maybe even more so. By 1970, 39 percent of southern black children attended majority white schools; the figure in the North was 28 percent.

The school desegregation crisis outside of the South had certain factors in common whatever city became inflamed: patterns of residential segregation and racial practices that contributed to de facto segregation, the shifting demographics of cities, and a crisis of cultural values that had more to do with issues of social class than with race. At the same time, each city had its own local circumstances that fanned the crisis. In Boston, the political mattered as much as the social, cultural, and economic. Charter reform in 1949 had replaced a ward-based city council with an at-large city council. The attempt to destroy the old district politics of the city may have been admirable, but the effect disconnected councilors and their neighborhoods at the very moment that the black population in the city was rapidly rising. As a result, blacks had little influence on city government.

Nor did they have a presence on the Boston School Committee, a group of elected officials that dated back to the 1640s and that governed educational policy and school assignment. The committee had shown little interest in the problem of racial imbalance; indeed, its policies seemed intent on perpetuating and deepening de facto segregation. For example, in 1961, it adopted “open enrollment.” Theoretically, the program would allow students to enroll in schools outside of their neighborhoods if space was available. The effect of the policy, however, was to accelerate the movement of white students out of schools with blacks, and not the integration of primarily white schools.

That same year, a revitalized and reenergized Boston chapter of the NAACP, whose Education Committee would be led by Ruth Batson, a researcher at Boston University, asked the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination to investigate the issue of racial preferences and school assignments. The commission ruled that race was a not a central factor in the actions of the committee, but experience among black parents seemed to belie the conclusion.

In 1961, as the NAACP considered its next steps, a new member was elected to the School Committee. Louise Day Hicks was, in some respects, an unlikely candidate for elected office. She attended law school while in her thirties, already married and the mother of two. Projecting a genteel image, she campaigned for the School Committee promising to take the politics out and put a touch of domesticity in. “The only mother on the ballot,” her slogan ran.

For two years she succeeded so well that she was elected chairwoman in January 1963. But then the system became unstable. The breakdown came after a series of meetings held between the NAACP and the Boston School Committee. Led by Ruth Batson, the NAACP sought acknowledgment from the committee that de facto segregation existed in Boston (thirteen schools were at least 90 percent black, and the budgets for those schools provided $125 less per pupil). In her statement Batson declared, “In discussion of segregation in fact in our public schools, we do not accept residential segregation as an excuse for countenancing this situation. We feel that it is the responsibility of school officials to take an affirmative and positive stand on the side of the best possible education for all children. This ‘best possible education’ is not possible where segregation exists.”

The battle between the parties, as J. Anthony Lukas suggests in Common Ground, was at first semantic. The NAACP wanted acknowledgment of de facto segregation. The Boston School Committee did not pretend that all was well with the schools but would not concede the point. “It’s like a picture on the wall,” one member said. “Once you admit it’s tipped you have to put it straight. We’re not admitting anything.” But what so many needed to hear was an admission of injustice, if not responsibility. On the evening of June 11, 1963, as the NAACP and the Boston School Committee met, President John F. Kennedy addressed the nation in response to Alabama governor George Wallace’s blocking of the entrance to the University of Alabama: “If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public, if he cannot send his children to the best public school available, if he cannot vote for public officials who represent him, if, in short, he cannot enjoy the full and free life all of us want, then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and stand in his place?”

Those words resonated deep in Kennedy’s hometown, among the liberals and the blacks and even members of the Boston School Committee. Louise Day Hicks had kept meeting with the NAACP, sometimes privately, to work out mutual language, and it seemed that they had agreed on a statement saying that “because of social conditions beyond our control, sections of our city have become predominantly Negro areas. These ghettos have caused large numbers of Negro children to be in fact separated from other racial and ethnic groups . . . In this city, so proud of its ‘Cradle of Liberty’ spirit and the home city of the President of the United States, it is only fitting and proper that we take the lead in recognizing the social revolution taking place across this nation for Negro equality.”

“Fitting and proper.” The phrase echoed Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address: “It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.” The southern civil rights movement had come north, and Boston had reconnected itself to its history in the struggle for freedom. But then Hicks balked. Angered at a leaked version that eliminated the phrase “beyond our control,” she withdrew the statement. The NAACP was planning a one-day boycott of the schools on June 18. Hicks, angry and strident, said, “If some black leaders would rather ‘play with words,’ then I am indeed disillusioned.”

It is naive to believe that had the original statement been released, the agony of the following decade might have been avoided. At the same time, so much of the controversy revolved around playing with words and rhetorical gamesmanship that the breakdown in discourse between parties was a political breakdown of seismic magnitude. More than eight thousand black students were absent from school on the “Stay Out for Freedom” boycott June 18. Some attended “freedom schools” set up in churches and community centers and learned about black history and the civil rights movement. Hicks, now unyielding in her position, brought new rhetoric to the crisis, words that set a tone for the pious and violent conflict of cultures that would follow: “God forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

In February 1964, Boston’s black children, along with students in New York, Chicago, and other northern cities, again boycotted the schools. That summer, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, which banned discrimination, protected voters’ rights, and supported actions taken to desegregate public facilities. In Massachusetts, two reports on school segregation were in the works. The first appeared in January 1965. Titled Report on Racial Imbalance in the Boston Public Schools, it was produced by the Massachusetts State Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights. The committee was chaired by Robert Drinan, a Jesuit priest and lawyer who was dean of Boston College’s School of Law and would be elected to Congress in 1970, and included a subcommittee on education led by Paul Parks, an officer with Boston’s NAACP. The report found de facto segregation in Boston’s schools, faulted the Boston School Committee’s neighborhood policies, and denounced racial imbalance in the schools because “it damages the self-confidence and motivation of Negro children,” “reinforces the prejudices of children regardless of their color,” and “results in a gap in the quality of educational facilities among schools.”

Several months later, the Advisory Committee on Racial Imbalance in Education, appointed by Owen Kiernan, the state commissioner of education, issued its report. The committee found forty-five racially imbalanced schools in Boston, schools with more than 50 percent black enrollment. Half of the more than twenty thousand black students in the city attended twenty-eight schools that were 80 percent or more black. The report, titled Because It Is Right—Educationally, concluded that “racial imbalance is educationally harmful to all children” and, in particular, “does serious educational damage to Negro children by impairing their confidence, distorting their self-image, and lowering their motivation.” Racial imbalance “represents a serious conflict with the American creed of equal opportunity.” Drawing heavily on social science research, which, in the decade since Brown, had grown more sophisticated and more unanimous in finding segregated and neighborhood schools antithetical to good education, the report recommended that steps be taken to correct the imbalance. Among those to be considered: “the exchange of students between other school buildings.” In other words, busing.

The Boston School Committee rejected the report, and Hicks seized on the one recommendation about busing and denounced it as “undemocratic, un-American, absurdly expensive and diametrically opposed to the wishes of the parents in this city.” She labeled the committee members “a small band of racial agitators, non-native to Boston, and a few college radicals who have joined the conspiracy to tell the people of Boston how to run their schools, their city and their lives.”

With the Kiernan report and the Boston School Committee response, what had started as semantic differences over the phrase “de facto segregation” metastasized into a deep-rooted cultural conflict in which both sides claimed to stand for an American tradition. It was a conflict in which cosmopolitanism and localism, liberalism and populism, butted against each other. Boston had a long tradition of activism and support of civil rights, and it had a long tradition of self-determination and ethnic pride. Both were in the ascendant in the 1960s; in the crisis over busing, they would be at war.

Motivated by the reports on racial imbalance, and inspired by Martin Luther King’s visit to Boston on April 22–23—a visit in which King admitted it would be “dishonest to say Boston is Birmingham” but “irresponsible for me to deny the crippling poverty and the injustice that exist in some sections of this community,” a visit in which King proclaimed that “Boston must become a testing ground for the ideals of freedom”—the state legislature passed the Racial Imbalance Act.

The act, the first of its kind in the nation, defined “racial imbalance” as a ratio between nonwhite and other students in public schools “which is sharply out of balance with the racial composition of the society in which non-white children study, serve and work.” It deemed racial imbalance to exist when the percentage of nonwhite students exceeded 50 percent of the total number of students in a school. If the School Committee failed to take action to eliminate the imbalance, the schools would lose millions of dollars in state aid to education.

The legislature’s desire to do something about de facto segregation may have been admirable, but the statewide act was passed with only one Boston representative voting for it. Hicks and other members of the Boston School Committee would make much of local communities being dictated to by legislators from outside of Boston who could easily vote their conscience when the results of their vote would have no impact on their suburban constituencies. “I am tired,” Hicks declared, “of nonresidents telling the people of Boston what they should do.” For years, the committee challenged the act legally and found ways to undercut its intent through policies of student assignment, enrollment management, and school construction. Over time, the state board of education withheld more than fifty million dollars in funds, and the number of schools defined as imbalanced rose from forty-five in 1965 to sixty-two in 1971.

Dismayed by the recalcitrance of the School Committee, which in August 1965 reversed an agreement to bus some students from overcrowded schools in Roxbury and North Dorchester to Brighton and Dorchester, black parents helped organize their own programs. The North Dorchester–Roxbury Parent Association, for example, took advantage of the open enrollment policy to bus black children to open seats in white schools. Called Operation Exodus and funded by the NAACP, labor unions, and money raised by parents, the program bused more than five hundred students by 1967. Even more successful was the Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity (METCO), founded in 1966. Funded by grants from the federal government and the Carnegie Corporation, METCO bused innercity black students in Boston to suburban schools. The state soon took over funding of the program, which cost two million dollars, and by 1974 was sending twenty-five hundred black children to superior schools in more than thirty suburbs.

But sending black children to the suburbs was not a way of carrying out the desegregation of Boston’s schools. The Racial Imbalance Act said that Boston’s schools had to desegregate; the Boston School Committee said that the segregation that existed was caused by residential and neighborhood patterns, not systematic discrimination, and that a solution was improvement of majority-black schools, not busing. To date, the discussion had been emotional but civil. The mayoral campaign of 1967, in which Louise Day Hicks ran as a candidate, polarized the sides and blurred the lines between arguments for local self-determination and racist demagoguery.

Hicks drew national attention when, in a September primary election, she beat nine male opponents, with 28 percent of the total and 50 percent more votes than runner-up Kevin White, with whom she would face a runoff. Even the Boston Red Sox in the World Series did not steal attention away from her. Taking her overwhelming reelection to the School Committee in 1963, and again in 1965, as a mandate, she ran, she said, “as a symbol of resistance.” To be sure, she was resisting desegregation (“You know where I stand” became a campaign motto), but she was also resisting being told what to do by the federal government, the state, and an assortment of activists who, she felt, did not necessarily represent the desires of the black community, much less the poor white working class who remained in a city that over the decades had seen its population plummet because of middle-class flight to the suburbs. Asked to explain Hicks’s popularity, one political observer said, “Most of the people who would have voted against Mrs. Hicks 10 years ago have moved out to Wellesley, Brookline and Newton.” Hicks was a one-issue candidate, and other interests in Boston united to give Kevin White, a well-connected politician, the victory. Still, Hicks had mobilized her base, a proud, patriotic group of people who had watched their economic status decline, felt deep ties to their local community, disdained the riots that had engulfed the nation (Watts, Newark, Detroit, even Roxbury), and resented all the effort on behalf of black rights. Asked about Hicks, one constituent said: “It’s not so much she’s anti-Negro as it is she’s for the white people. And why not? There was no civil rights when our people were coming up.”

By 1970, the debate did not focus on the problem of desegregation but on the problem of busing. Before busing became identified as a Boston issue, it exploded as a national trauma. On April 20, 1971, the Supreme Court issued its decision in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education. Darius Swann, a theology professor, sued the school board when his six-year-old son was prevented from attending a local integrated elementary school. Despite a desegregation plan put in place in 1965, two thirds of the twenty-one thousand black students in Charlotte attended twenty-one schools that were almost exclusively black. The Court was determined, seventeen years after Brown, to articulate the guidelines by which school authorities would “eliminate from the public schools all vestiges of state-imposed segregation.” Writing for a unanimous Court, Chief Justice Warren Burger discussed the importance of such issues as constructing new schools and closing old ones, the allocation of resources, the assignment of faculty as well as students, and transportation. On this last issue the Court observed: “Bus transportation has been an integral part of the public education system for years, and was perhaps the single most important factor in the transition from the one-room school house to the consolidated school. Eighteen million of the Nation’s public school children, approximately 39%, were transported to their schools by bus in 1969–1970 in all parts of the country.” The Court concluded that “we find no basis for holding that the local school authorities may not be required to employ bus transportation as one tool of school desegregation. Desegregation plans cannot be limited to the walk-in school.”

The Supreme Court may have given its support to busing as a remedy for achieving desegregation, but polls suggested that more than 80 percent of the American people opposed busing. In Pontiac, Michigan, in August 1971, protesters dynamited a half dozen buses sitting at a depot. In San Francisco, Rochester, and other cities, parents organized in opposition to busing plans. The comments of the president emboldened the protesters: Richard Nixon declared, “I have consistently opposed the busing of our Nation’s schoolchildren to achieve a racial balance, and I am opposed to the busing of children simply for the sake of busing.” The White House proposed a constitutional amendment banning busing, and Congress regularly debated the issue while taking other actions, such as prohibiting the use of federal funds for busing, to show its disdain.

On November 15, 1971, Time’s cover article was titled “The Agony of Busing Moves North.” The editors trod cautiously, trying to be fair to all sides: “it is doubtful that white parents have so strong a right to choose a specific public school for their children, but it is even more doubtful that they should be forced by law to have their offspring bused where their safety is endangered or where they will demonstrably suffer along educational lines.” Still, busing was needed, they thought, because “until bad schools improve and neighborhoods integrate, to outlaw busing would be to run the risk that the dangerous gulf between two nations—one black, one white— could grow even wider.”

In March 1972, dismayed by the lack of progress being made against the Boston School Committee in the state courts, the NAACP, on behalf of fifty-three plaintiffs, filed suit in federal court against the Boston School Committee. Tallulah Morgan was listed as the first plaintiff, and James Hennigan was chairman of the Boston School Committee. Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr., a graduate of Holy Cross and Harvard Law and confirmed to the district court in 1966, was chosen to hear the case of Morgan v. Hennigan. It would have taken any judge time to work through the issues and case law, but Garrity was not any judge. He was meticulous, thorough, and exacting. J. Anthony Lukas noted that “unlike other judges, who delegated heavily to young law clerks, Garrity read everything that crossed his desk, often working twelve hours a day, and such diligence meant that years might go by before he decided a complex case.”

Morgan v. Hennigan required Garrity to go back to the 1950s to review the actions of the Boston School Committee and the state board of education. It required him to familiarize himself with court actions since Brown, not only at the federal but also at the state level, cases from cities all over the country—including Springfield in 1964, where a district court judge ruled against de facto segregation but was reversed by the Court of Appeals. It required him to read countless filings, hear testimony over a two-week trial, and stay abreast of new developments that seemed to be emerging almost daily. For example, a year into the case, the Supreme Court decided in Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado that “unlawful segregative design on the part of school authorities,” even where schools had not been segregated by law, was impermissible. Finally, the case required that, in the event he found in favor of the plaintiffs, there was a remedy for him to impose.

After more than two years, on June 21, 1974, Garrity handed down his decision, which ran more than 150 pages. Systematically and methodically he inched toward a conclusion. He noted: “Eighty-four percent of Boston’s white students attend schools that are more than 80% White; 62% of the black students attend schools that are more than 70% Black. At least 80% of Boston’s schools are segregated in the sense that their racial compositions are sharply out of line with the racial composition of the Boston public school system as a whole.” The question was how it got that way, and the answer, Garrity ruled, touched on every aspect of the school system including enrollment patterns, districting, feeder systems, allocation of resources, and distribution of faculty. Drawing on the transcripts of Boston School Committee meetings, among other sources, Garrity found members deliberately dragging their feet, rationalizing their actions, and employing explicitly racial reasons for their decisions, all designed, he believed, to perpetuate segregation. By the time he was done, his conclusion was inescapable, as much axiom as opinion: “The defendants have knowingly carried out a systematic program of segregation affecting all of the city’s students, teachers and school facilities and have intentionally brought about and maintained a dual school system. Therefore the entire school system of Boston is unconstitutionally segregated.”

Because Garrity’s decision came with less than three months to go before school started, there was no time for him to construct a remedy. As a result, in this first phase of the decision (Phase II would come a year later, in September 1975), he chose as the remedy a plan proposed by the state board of education and already ordered to be implemented by the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts as a result of a state lawsuit that had been decided in October 1973. That plan was designed by Charles Glenn, an Episcopal priest and civil rights activist who, in 1971, had been appointed the head of a newly created Bureau of Equal Educational Opportunity. The plan called for reducing the number of imbalanced schools by half by busing some seventeen thousand students. Its most controversial element left South Boston and Roxbury paired for cross-busing. Educators at the time knew this was a toxic mixture. South Boston had been the center of opposition to busing for nearly ten years. And the students of South Boston and Roxbury were among the poorest in the city. Advisors to the state, such as Louis Jaffe of Harvard Law School, warned early in 1973 that “this part of the plan should be restudied,” but it was not, and Garrity implemented it—though he admitted from the bench that he had not studied it. Perhaps he had not even read it. Having labored so hard to reach a decision, it seems Garrity’s thoroughness of purpose abandoned him when it came to choosing a remedy. South Boston’s William Bulger, repeatedly elected to the Massachusetts House in 1961 and, starting in 1970, the Senate, and a leading opponent of busing, later said that Garrity had “the sensitivity of a chain saw and the foresight of a mackerel.”

Garrity’s decision came at a moment when the opposition to busing was intensifying. On the national scene, the House of Representatives on March 26, 1974, voted for a constitutional amendment that prohibited busing. On the state scene, the Massachusetts legislature voted in October 1973 to repeal the Racial Imbalance Act, and although the governor vetoed the action, he subsequently supported an amendment of the act that substantially diluted it. On the local scene, in February 1974, Louise Day Hicks, now back on the City Council after spending one term in Congress, and State Representative Raymond Flynn, formed Massachusetts Citizens Against Forced Busing—a group that, along with the Save Boston Committee, would be absorbed into the overarching anti-busing organization Restore Our Alienated Rights (ROAR). “Save Boston Day,” a rally held on April 3 at the statehouse, drew thousands of people. Mayor White expressed the seemingly contradictory position of many Bostonians when he said, “I’m for integration, but am against forced busing.”

Not only was busing anathema, but some had even begun to question the assumption that desegregation was educationally beneficial to black children and that education could serve as a vital tool for transforming society. Ever since Brown, which cited “a feeling of inferiority” that might afflict blacks in segregated schools, the assumption that black children profited educationally from integrated classrooms had been an article of faith. In 1966, a report issued by sociologist James Coleman, Equality of Educational Opportunity, tested this conviction, and, in fact, many of his findings challenged the belief. For example, Coleman discovered that issues of class and family had far more impact on educational achievement than differences in schools, which he found to be fewer than expected. But almost no one at the time seized on these results. Instead, educators and activists read and codified those parts of the report indicating that black students performed poorly compared to white students and predicting improved test scores for black children in integrated classrooms. The following year, a report issued by the United States Commission on Civil Rights, Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, concluded that “Negro children suffer serious harm when their education takes place in public schools which are racially segregated.”

By the early 1970s, however, a “crisis of doubt” had emerged about the equalizing benefits of education and the means to attain them. David J. Armor, a Harvard sociologist, specifically studied the evidence on busing and education and found that “busing is not an effective policy instrument for raising the achievement of black students or for increasing interracial harmony.” Integration, he argued, did not have an effect on academic achievement or aspirations for college and future occupations. The data even suggested that rather than “reduce racial stereotypes, increase tolerance, and generally improve race relations . . . integration heightens racial identity and consciousness, enhances ideologies that promote racial segregation, and reduces opportunities for actual contact between the races.”

These were disturbing conclusions that raised fundamental questions about the relationship between public policy and social science. Not surprisingly, other sociologists found fault with Armor’s study, arguing that he presented selected findings, his work suffered from methodological problems, and he held too high a standard for what constituted achievement. Whatever the merits of the argument, at the precise moment Garrity was preparing to issue his decision, the social assumptions that underlie Brown were under assault, and the opponents of busing had found unexpected support for their position.

On September 12, 1974, the first day of school, the students and parents who gathered outside South Boston High School did not need a Harvard sociologist, or the president of the United States, for that matter, to confirm for them what they had known for years: busing would not work, probably not anywhere, but certainly not in their community. They called it forced busing—forced on them against parental control and will; forced on them by academics and activists who lived outside the community; forced on them by residents of the suburbs (who themselves had recently been exempted from desegregation orders by the Supreme Court in Milliken v. Bradley, a Detroit case); forced on them by the media, especially the Globe, which became anathema to anti-busing activists; in sum, forced on them by “unaffected proponents” for whom making a sociological experiment of poor black and white working-class students was easy, since their own children were not involved. And it wasn’t only South Boston and Charlestown that were opposed. There were parents in Roxbury who had begun to wonder about the benefits of integration, who had been drawn to the black power movement, and who thought that better schools and teachers and curriculum in their own neighborhoods would provide the education they as parents sought for their children.

On September 12, 1974, an upheaval that had been developing for over a decade—or maybe longer, all the way back to the beginnings of Boston’s long history of race relations—had arrived. It came out of good intentions, and good intentions gone awry, and some intentions that were not so good to begin with. It came out of some circumstances that were national in scope and some that were purely local. It came out of demographic shifts, steadfast beliefs, and failures of leadership on many different levels. The crisis hit in the form of a federal court order. And yet, as meager as the preparations had been in the three months since Garrity’s decision, at seventy-nine of the eighty schools affected by the court’s decision, the buses rolled without major incident. At South Boston High School, however, the crisis unleashed hatred and violence that threatened to destroy the city.

On that first day, 66 percent of the students in Boston attended school, but at South Boston High School, out of an expected total enrollment of 1,539 (797 black), there were 68 white students and 56 black students. At Roxbury, 13 white students attended. As the buses rolled into South Boston, they were greeted by a crowd of several hundred chanting “Here we go, Southie.” Racist graffiti had been painted on the school walls. Someone threw a rock in the morning, and more rocks, bricks, and eggs were thrown in the afternoon. “Get those niggers out of our school,” shrieked one protester. Some carried signs that read BUS ’EM BACK TO AFRICA. The Progressive Labor Party was also there, with a sign that read FIGHT RACISM, FIGHT THE BOSSES. Many protesters did not like the Progressives any more than any other outsider, and fists flew. Some photographers found themselves under assault as well. The police, many of them from the very neighborhood now under siege, had an impossible job to do and under trying circumstances tried to preserve order the best that they could. Politicians and editors, seeking to cast events in a positive light, characterized the day as “generally peaceful” and “a fine beginning.” But it was clear that the protesting, chanting, and pelting had only just begun.

Newspapers across the country took note. The Dallas Times Herald observed that “it must be one of the greatest ironies of our time when black children quietly and peacefully board buses to desegregate schools in Selma, Atlanta, Richmond and Dallas, but are stoned in Boston.” In Little Rock, the Arkansas Gazette said that busing was being used as an excuse by northern segregationists: “In Boston as in Little Rock an adequate desegregation of schools cannot be accomplished without transporting a portion of the pupil population to schools not in their immediate neighborhood.” Closer to home, the Hartford Courant did not excuse the behavior but explained it in terms of class, not race: “South Boston’s Irish certainly are not opposed to blacks solely because of color difference. Nor is their concern only with schools, they also fear competition with blacks over jobs, housing and social services.” Whatever the volatile mixture of racial hatred and class resentment, the Boston Globe lamented that “Boston was supposed to be an enlightened city, the Athens of America. Now our collective conscience is stunned by brutal attacks on children in school buses and on innocent citizens going about their business on our streets.”

After another day in which attendance dropped and boycotts and protests continued, the weekend arrived. On Monday, anti-busing leaders Louise Day Hicks, Michael Flaherty, and William Bulger issued a “Declaration of Clarification.” Seeking to defend South Boston against the accusation that its residents were all racist, the authors denounced “the vicious impression that they are a people opposed to black people and their legitimate aspirations.” At the same time, the declaration made it clear that they were afraid of “crime-infested Roxbury,” where “there are at least one hundred black people walking around in the black community who have killed white people during the past two years.” Seeking to offset the caricature of South Boston as occupied by violent Irish hooligans, the hastily prepared statement perpetuated its own caricature of Roxbury as peopled by a criminal underclass. Black parents and white dreaded sending their children into hostile territory, and the stereotypes of South Boston and Roxbury spread by journalists and politicians, and reinforced by racial assaults in both districts, deepened the crisis.

White and black liberals who supported busing may have felt in some way that this was their civil rights movement, some ten years after the memorable marches and protests led by Martin Luther King, but it was the anti-busing activists who employed the tactics of the civil rights movement by organizing school boycotts, holding prayer vigils, and engaging in acts of nonviolent protest that led to arrests. Jim Kelly, of the South Boston Information Center, recalled that “a lot of what we did was copped from the peaceful demonstrations of the civil rights movement.” He claimed never to condone or be involved in threats or violence, but he was also unable to keep the crowds under control.

The violence, and rumors of violence, escalated and spread. There were incidents not only at South Boston High School but at Hyde Park, North Dorchester, and Roslindale. The presence of the Tactical Police Force (TPF) in South Boston further inflamed the residents, who felt under siege by officers, some of whom were themselves residents. And with Boston as the national story, groups descended on South Boston, not only progressive groups but racist ones such as the National Socialist White People’s Party and David Duke’s Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, groups repudiated by the residents of South Boston in no uncertain terms. Each day was another obstacle course to be navigated by parents and police, protesters and politicians, students and administrators. Attendance fluctuated based on what was taking place. On October 2, the first of many riots inside South Boston High School occurred when a shoving match in the cafeteria turned into lunch trays flying and rumors of worse. “Mass hysteria” is how one teacher described it. The following day, nearly two hundred fewer students came to school. And the next day, with major anti-busing demonstrations held, citywide school attendance dropped to 51 percent.

At times, the violence turned life-threatening. A brick found its way through a TPF windshield, and a local South Boston establishment and its patrons got payback. A Haitian man drove his car on the wrong block at the wrong time and nearly died when he was dragged from the vehicle and severely beaten. A white student at Hyde Park High School was knifed; two months later it happened again at South Boston High School, an event that nearly led to a full-blown race riot and shut down the high school for almost a month. For every action there was a reaction, and retaliation often became the only objective. The governor called for federal marshals or the National Guard, but the requests were refused. President Gerald Ford did not help ease tensions when he announced on October 10, “I have consistently opposed forced busing to achieve racial balance as a solution to quality education and, therefore, I respectfully disagree with the judge’s order.” Whatever the president was thinking, his words gave sustenance to those who were resisting peacefully as well as those operating outside of the law. “Open guerilla warfare” is how one official described the scene in South Boston and Roxbury.

On March 5, 1975, some four hundred anti-busing protesters attended a reenactment of the Boston Massacre. They conducted a mock funeral procession behind a coffin carrying the corpse of Liberty with a sign attached: RIP B. 1776–D. 1974.” YOU THINK THIS IS A MASSACRE, JUST WAIT, read one placard. BOSTON MOURNS ITS LOST FREEDOM, read another sign. They chanted, “Garrity’s killed liberty.” Garrity’s tyrannical court order, in their eyes, was comparable to the tyranny of Parliament and King two hundred years earlier. During the reenactment, when shots were fired, the protesters all fell to the ground. A black man had been among the original victims of the Boston Massacre in 1770, but not here, not at this reenactment.

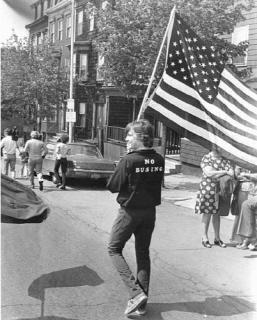

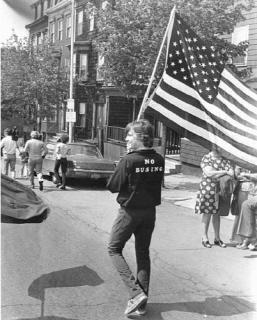

One of the ugliest incidents occurred on April 6 when, after visiting a school in Quincy, Senator Edward Kennedy came under attack. Kennedy supported desegregation and urged his constituents to obey the law. Moreover, he was close to Garrity, who was denounced at times as “Kennedy’s puppet.” This was not the first time protesters turned on him. At a rally on September 9, 1974, he was shouted down and had tomatoes thrown at him. Now, at Quincy, a crowd of two to three hundred not only jeered and taunted but slashed the tires of his car and threw rocks. And at least one person turned her American flag against him. According to one editorial, “the irony of this exhibition of un-American conduct was blatantly illustrated by the action of a woman in the crowd. As she bombarded Kennedy with abusive language, she kept jabbing at him with the point of a small American flag standard.”

However much protesters embraced the flag, it became increasingly difficult for opponents of busing to defend against the charge not only of being un-American but also racist. The venom of John Kerrigan, chairman of the Boston School Committee since 1968, who according to journalists referred to blacks as “savages” and once said of a black reporter that “he was one generation away from swinging in the trees,” did much to cast all busing opponents as racists. Kerrigan continually called for a metropolitan solution to the problem of segregated schools, asking, “Isn’t racial isolation of white students in suburbia every bit as damaging and insidious” as the racial isolation of blacks? In response, educators such as Jonathan Kozol denounced Kerrigan for using the idea of busing to the suburbs as “a mask for his racist policies.”

The fear, violence, and racism reinforced one another. Some saw in the pattern a long history in America of using and manipulating race in such a way as to divide those with common class interests. “The Irish have much to learn through the association of their children with blacks,” wrote one minister. “They might discover that their real enemy is the system that has kept them in the ghetto of South Boston, as it has kept blacks in the ghetto of Roxbury.” The distinguished Harvard psychiatrist Robert Coles, who had studied the debilitating effects of segregation on children, offered a similar analysis: “The ultimate reality is the reality of class, having and not having, social and economic vulnerability versus social and economic power—that’s where the issue is.”

Man with flag, c. 1976 (NORTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS)

But the issue of class—of the inner city versus the suburbs— never had the traction some anti-busing leaders hoped for. State Senator William Bulger despaired over “the burden of public contempt and ridicule . . . growing out of the unremitting, calculated, unconscionable portrayal of each of us . . . as unreconstructed racists.” Desiring “to assert the natural rights of parents to safeguard the education of their children in their traditional local schools does not mean,” he declared, “that we oppose the ideals of integrated education . . . It does not mean that we are rejecting the ideals of the brotherhood of man under the fatherhood of God.”

How to achieve the ideal was the rub. All through the year, Garrity was trying to plan for Phase II of the desegregation of the schools, to go into effect in September 1975. The Boston School Committee, ordered to submit a plan, refused to do so after the stabbing at South Boston High School. Other groups were not as unwilling, and Garrity received plans from the state, from the NAACP, and from a group of special masters and experts he had selected. The Masters’ Plan, which divided the city into nine community school districts and would have reduced busing, eliminating it between South Boston and Roxbury, seemed promising and received a favorable response from most quarters of the city. The Boston Globe praised it as following in the tradition of Solomon. But on May 10, 1975, when Judge Garrity issued his order for Phase II, he had revised the Masters’ Plan in such a way that rather than decreasing busing, it actually increased it from fewer than fifteen thousand students to more than twenty-two thousand.

No one was happy. The mayor expressed regret and disappointment. The NAACP thought too much of the burden of desegregation fell on the black community. The Boston School Committee called it a “disaster.” Hicks accused Garrity of creating a “legal monstrosity” that would accelerate middle-class white flight to the suburbs and establish the very entity he sought to eliminate: a racially divided city. At the moment of Garrity’s decision, a new report issued by James Coleman, whose original study a decade earlier was used to justify busing, concluded that “programs of desegregation have acted to further separate blacks and whites rather than bring them together” and that “busing does not work.” Parents received in the mail a booklet from the court explaining their options under Phase II and were given eight days to make their decisions. They felt pressured and confused. The first school year under a court order for desegregation had come to an end. The second did not promise to go any better.

In September 1975, not only were there the usual spasms of protest and violence, but now Charlestown, which demographically was akin to South Boston and had been excluded from busing in Phase I, also entered the fray. On the first day, only 315 of the 883 students assigned to Charlestown High attended. At the end of the month, teachers throughout the city went on strike over their contract and established picket lines outside the schools. It was settled within a week, but attendance took another hit. Headmasters might declare on the morning address system, “Remember, you’re here to learn. That’s the purpose of this school,” but few actually believed that there was any meaningful learning taking place.

In November, Judge Garrity began to hold evidentiary hearings to determine whether the court’s desegregation order was being implemented at South Boston High School. After taking testimony from students and administrators, and personally visiting the high school twice, Garrity ruled on December 9 that the Boston School Committee would no longer run the school. Instead, it would be placed in receivership and run by the court. He also ordered the headmaster, Dr. William Reid, and administrative staff transferred. A national search for a new headmaster for South Boston High School led to the appointment on April 1 of Jerome Winegar from St. Paul, Minnesota, where he had established a reputation as an innovative and progressive educator.

Winegar’s appointment was opposed by teachers and parents who thought that Dr. Reid had been treated unfairly and who were smarting over the high school being placed under direct control of the court. The battle over busing seemed to be turning. Garrity’s decisions were being upheld by higher courts. A year earlier, Garrity had allowed three intransigent School Committee members who refused to adhere to his order to submit a desegregation plan to avoid fines for civil contempt, and his decision served only to encourage militant opposition by the majority of the committee. No more; the judge had had enough.

To protest Garrity’s actions and Winegar’s appointment, and to call for an end to busing, students at Charlestown High and South Boston High organized a boycott of classes on Monday, April 5. That day, one teacher at South Boston “worked individually with the black students” because there were no white students in her class. The students and chaperones traveled to City Hall Plaza, where they were greeted warmly by Louise Day Hicks and recited the Pledge of Allegiance. They filed outside into the mild morning air. At that moment, a black man came into view. Then, in one click of a photographer’s shutter, the anti-busing claim that the movement was not driven by racism, and that protesters were patriotic defenders against tyranny, came undone.