In the immediate aftermath of the incident on April 5, Forman had no idea whether he had any newsworthy images, and he was in no rush to get back to the office. As he walked around the Federal Building, down by Post Office Square, he ran into a Herald American reporter, Joe Driscoll. Driscoll asked, “Did you hear what happened at City Hall? A black guy got beat up by a flag.”

“I got it,” Forman replied.

Driscoll screamed, “What! You got it? You better get in the office.”

Forman retrieved his car and returned to the office sometime before noon.

He went to the darkroom and developed the pictures. He had two choices: do it by hand, bathing the negatives in chemicals, or put the film through a Versamat machine, which quickly developed the negatives but every so often turned those negatives to confetti.

Forman was impatient to see what he had. He did not like the printing process and had little desire to make magic in the darkroom by playing with contrasts. He always just wanted to get in and get back out. “You do not have the picture until you see the developed negative” is a truth every photographer lives by. Once, early in his career, Forman took some shots, entered the darkroom, and discovered that he had forgotten to load film in the camera. He hated the darkroom, so, despite the risk of his roll being eaten, he fed it through the machine.

The pictures came out unharmed, and Forman went to the light table. He looked at them and did not get overly excited. In that moment of first seeing what he had, he did not recognize the power of one of those images.

But as the editors gathered in the afternoon, excitement and nervousness began to build. Every day at five o’clock they met to lay out the paper. An argument ensued over whether to run Forman’s photograph. One editor urged against it, fearing that it would inflame racial tensions and cause riots. But Myer Ostroff, head of the photo department, and other editors, argued that it had to run on page one.

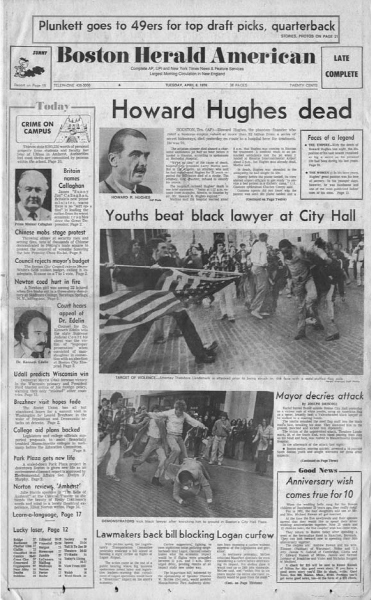

The national story that day was the death of Howard Hughes. Sam Bornstein, the executive editor, knew that the headline and the top half of the front page would be devoted to Hughes. But the local story was the anti-busing movement, and the Herald American was a city newspaper. Before the editors’ meeting broke, Bornstein had made his decision. The disturbing, potentially explosive photo of a protester using an American flag as a weapon against a black man would make page one.

By featuring Forman’s photograph, editors were doing what editors had been doing with photographs for decades: using them to help sell newspapers. Although photography first appeared with the daguerreotype in 1839, technological restraints made use of the camera to record events impractical. Lengthy exposure times and cumbersome equipment allowed only for portraits or images of still subjects: this in part explains the popularity of pictures of the dead in nineteenth-century photography. Even during the Civil War, technology did not allow photographers to capture action. There are thousands of images of the era, but nearly all are of battlefields and armaments and soldiers in fixed positions.

By the end of the century, dramatic changes had taken place. The daguerreotype, a one-of-a-kind original, gave way to film processes that produced a negative, and those processes themselves became refined with the creation in the 1870s of the dry plate process, which meant photographs did not have to be developed immediately. A decade later, plates gave way to rolls of film. At the same time, the size of the camera shrank. In the 1880s, George Eastman introduced a camera with the slogan “You press the button—we do the rest.” By century’s end, the “Brownie” camera (“operated by any school boy or girl”) went on the market for one dollar, and photography became a national hobby and obsession. These light, portable cameras allowed snapshots to be taken of everything and everyone. For children, the camera might have been an elaborate toy. But for journalists, it became an indispensable tool.

While we remember most of the muckraking journalists of the turn of the twentieth century for their writings—Lincoln Steffens, Ida Tarbell, Upton Sinclair—others seized on the power of the camera to reveal and tell a story. In 1890, Jacob Riis published How the Other Half Lives, a book of words and pictures depicting life among the poor of New York. His camera, with a new accessory, flash powder, exposed the darkest places of the city. Perhaps most significant of all, a new printing technology, the halftone process, allowed for the first time the reproduction of photographs in books, magazines, and newspapers. Invented in the 1880s, the technique divided a photograph into thousands of black dots by covering it with a screen and rephotographing it. The pattern of dots could then be printed in a book or magazine.

Prior to the halftone process, only engraved images such as woodcuts appeared in print. The cultural transformation ushered in by the halftone process cannot be exaggerated: photographic reality became everyday reality, and photographs became an indispensable part of reporting the news. In 1897, the New York Tribune became the first newspaper to use photographs on a regular basis, and muckraking magazines such as McClure’s also relied on photographs as evidence for the stories they reported. Photography and the news went hand in hand, as evidenced by the shots of the aftermath of the earthquake of 1906 that appeared in the San Francisco Examiner. Photographs themselves became news as photographers competed for exclusives, and front page pictures helped sell newspapers. On January 12, 1928, Thomas Howard, a photographer for New York’s Daily News, which has a camera icon in its logo, sneaked a miniature camera into Sing Sing and snapped a photograph of Ruth Snyder at the moment of her electrocution. The image appeared on the front page the next day, and the paper is said to have printed an extra 750,000 copies to meet the demand. In 1936, Henry Luce began publishing Life, a weekly photojournalism magazine that, over nearly forty years, did as much to shape American culture as to document it.

The Pulitzer Prize Board first awarded an annual prize for photography in 1942. In 1968 they split the prize into two: spot news photography and feature photography. Forman was a spot news photographer, and it was for spot news that he submitted both Fire Escape Collapse and The Soiling of Old Glory for Pulitzer consideration. Whereas Forman stood alone in the back of the building when he shot the fire in Back Bay, he was one of several photographers on the scene when Landsmark was attacked. Comparing his photograph as it appeared in the Herald American with the picture in the Globe underscores the visual drama that Forman alone captured that day. It also illustrates the competition between the dailies and the way editors used photographs not only to report the news but also to help sell papers.

Editors featured Forman’s photograph at the center of page one. The death of Howard Hughes may have been the lead, but the composition of the front page draws the eye to the center photograph and the headline “Youths Beat Black Lawyer at City Hall.” The photograph itself is cropped at the top, making the scene even more compressed and claustrophobic. The powerful diagonal thrust of the flag cuts not only the picture but the page in half. It stands above the fold. Using a second, square Forman photograph below it boxes in the central picture and adds additional force to the page. The two photographs are out of sequence: the kicking of Landsmark occurred before the assault with the flag. The arrangement may have deceived viewers, but in selling papers drama trumps chronology.

The Globe photographer, Ed Jenner, found himself along with the other media behind the marchers when the melee broke out. His photograph shows Landsmark being punched, but the image is not particularly dramatic. There are too many people in the center of the scene. The flag is in the background, but it plays no role in the composition. Jenner’s photograph shows a moment before the attack with the flag. It was the clearest picture of the assault that he got, but the image carries little impact, if only because the viewer has to work too hard to make any sense of the scene. The Globe’s editors placed the story at the bottom of page one with the headline “Black Man Beaten by Young Busing Protesters.” On this day, the Herald had beaten the Globe.

Examining the position of The Soiling of Old Glory on the front page of the Herald American is only one aspect of reading the image. Forman’s photograph is a masterful picture not simply because of what it depicts and where it appeared but because of how it is composed. Several photographers took pictures of the incident at City Hall Plaza, but only Forman took a picture that seems historic, an image that we feel as much as we see. It is worth asking what makes Forman’s photograph so powerful. How do we read The Soiling of Old Glory?

One place to begin is with the visual textures of the image. It seems a bit blurry. Indeed, because he was shooting at a relatively slow shutter speed of 1/250, there is subject movement in all the frames, but the effect is to enhance the sense of frenzy. The play of light and dark is essential to the scene. The steel shaft’s bright line of white splits the picture in half and draws our eye to the literal center. The photograph is slightly out of focus but for the tip of the shaft, which hangs in suspended animation. The flag bearer’s dark clothes place the pole and flag in relief: the whiteness of the stars and stripes in the foreground is mirrored by the pulsing brightness of the background. Because of the 20 mm lens, there is some distortion at the edges and Rakes appears a bit elongated, making him look even more menacing. The event drama of white against black is replayed in the visual drama of light against darkness: the plaid shirt and white pants of the youth in the center, the white shirt of the man turning away, Landsmark’s white sleeve from his rumpled suit. The stream of light carries our eye across the scene, from left to right, just as the darkness of the building on one side gives way to brightness on the other. It also takes us from the darkness of the foreground to the light of the background, the sun bouncing off of the windows at the center rear.

Boston Herald American, April 6, 1976 (COURTESY STANLEY FORMAN)

Boston Globe, April 6, 1976 (BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY)

The visual textures that give the image such power are not only black and white but geometric as well. The cobblestone pavement provides strong vertical lines that direct our eyes from foreground to middle ground, where the horizontal action is taking place. The stones provide a grid, a field of action on which the incident rages. Our eyes follow the lines back, through a corridor bordered by the granite blocks of the building on the left and the alabaster white of the building on the right. The two buildings create parallel lines that help give the photograph depth and exaggerate the feeling of confinement and claustrophobia. There is no escape to the rear, which carries the viewer back into Boston’s past, to the Old State House, whose Georgian facade sits bathed in sunlight.

Ahead, the direction toward which Landsmark struggles, the lane opens up onto City Hall Plaza. Built between 1963 and 1968 as part of an urban renewal program, and in an attempt to centralize government services, the plaza from the start was ridiculed and reviled. Indeed, the Project for Public Spaces placed it at the top of its list of the worst squares and plazas in the world. (Place de la Concorde in Paris and the United Nations Plaza in San Francisco rank second and third.) The spaces between the buildings are vast, the plaza seems shapeless, and the complex is cut off from any of the surrounding attractions such as Faneuil Hall and Quincy Market. Indeed, City Hall Plaza seems to have been completed with an eye toward creating a public space that impeded the possibilities for protest.

Just as space is critical to an understanding of the photograph, so is time. Not so much the time of day, though the bright light of an early April morning illuminates the scene, but historic time, which we are reminded of precisely because of where the light is hitting brightest: in the rear, on the Old State House. According to the Bostonian Society, the Old State House is the oldest surviving public building in Boston. Built in 1713, it housed the government offices of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the council chamber of the royal governor, and the meeting place for the Massachusetts Assembly, as well as the Suffolk County courts and the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. Only in 1798, with the opening of a new state house on Beacon Hill, did the building cease being used by state officials.

The building is most notable for another reason, and that reason is important to a reading of Forman’s photograph. We carry historical and visual memories and associations to every image that we see. Sometimes we are conscious of those associations, as might be the photographer who plays off of them. For example, when Gordon Parks posed Ella Watson in front of an American flag, he relied on viewers’ knowing Grant Wood’s American Gothic, which had already become a visual icon in American culture. More frequently, it is not that we are conscious of a specific connection but that the composition of any one image suggests the forms, positions, and expressions of others, and those associations deepen the reading of any single picture.

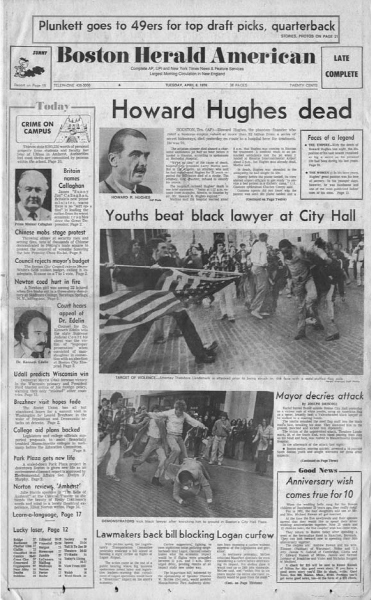

The event and image that The Soiling of Old Glory brings readily to mind are the Boston Massacre and Paul Revere’s engraving of the scene. On the evening of March 5, 1770, following an altercation between an apprentice and a British sentry, a crowd gathered by the customs house and began taunting a group of soldiers. The British army had been in Boston for nearly eighteen months, sent to maintain order following protests against various parliamentary acts. The crowd heckled the soldiers and threw icy snowballs at them. The soldiers, led by Captain Thomas Preston, tried to disperse the throng. Tensions mounted. With bayonets fixed, the soldiers prodded the crowd. And then the British soldiers opened fire. Several died on the spot; others succumbed later.

Gordon Parks, Washington D.C. Government Charwoman [Ella Watson], 1942 (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Three weeks later, Revere advertised for sale his broadside The Bloody Massacre Perpetrated in King-Street. Primarily a master silversmith, Revere also worked as a copper plate engraver, creating illustrations for books and magazines. His depiction of the massacre is one of the most famous prints in American history, a piece of political propaganda that fueled anti-British sentiment. Revere stole the design from the artist Henry Pelham, who was not at all happy about the engraver’s thievery. Pelham wrote Revere, “I thought it impossible as I knew you was not capable of doing it unless you copied it from mine and as I thought I had entrusted it in the hands of a person who had more regard to the dictates of Honour and Justice.”

Paul Revere, The Bloody Massacre Perpetrated in King-Street Boston on March 5th, 1770, 1770 (AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY)

Within five years, Pelham would return to England, a loyalist, and Revere would take the ride that, in time, transformed him into a folk hero. Revere’s print would find its way into the homes of colonists, who often paid extra to have it hand-colored. His broadside dramatizes the event, making the soldiers more orderly and organized than they were, depicting the crowd as passive, using words (the customs house is labeled “Butcher’s Hall”) to drive home his message. We feel enclosed in the same space as the protesters and soldiers. Our eye follows the volley, and we mourn the fallen along with the shawled woman at the center of the crowd.

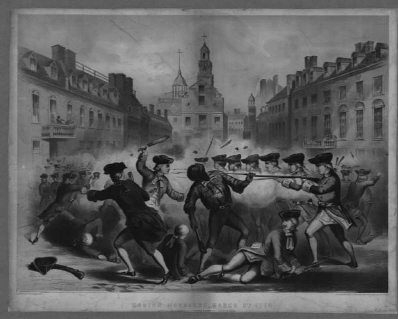

The connections, both historical and visual, between Paul Revere’s engraving and Stanley Forman’s photograph are striking. The assault upon Landsmark took place in the literal shadows of the site of the Boston Massacre; the Old State House is the background in Revere’s engraving as in Forman’s photograph. Both images feature enclosed, claustrophobic spaces, and architectural shapes and textures, that create depth and confine the action. Both provide strong horizontal lines to guide the eye. In both images, the balance of light and dark, even in the colored versions of Revere’s print, add drama to the scene. That the assault on Landsmark took place in 1976, as the city was preparing for the summer Bicentennial celebration, only adds to the resonance between the two images.

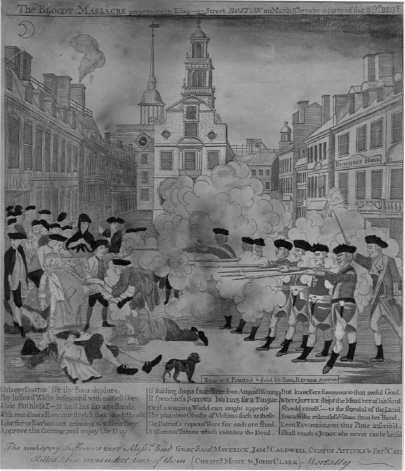

At a different level, so too does the story of Crispus Attucks, the black man considered the first victim of the Boston Massacre. Attucks was a runaway servant, a sailor and ropemaker in his forties who was a familiar figure among the working class of Boston. John Adams, who defended the British soldiers at their trial, identified the protesters as “a motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and mollatoes, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tars,” and he identified Attucks as an instigator who grabbed a soldier’s bayonet and struck a blow. But most patriots in Boston treated him as a martyr in the cause of liberty, and he was buried in hallowed soil at the Granary Burying Ground.

Only in the mid-nineteenth century did Attucks become fully transformed into a black Revolutionary hero, a symbol not simply of liberty but of the abolition of slavery. His resurrection came at the hands of William Cooper Nell, a black Boston historian who in 1855 published Colored Patriots of the American Revolution. Nell opened the book with a chapter on Attucks and a renewed call for a monument to the fallen hero. Boston’s black community embraced the cause, and on March 5, 1858, a year after the Dred Scott decision, which ruled blacks were not citizens, held a Crispus Attucks Day. By then, an artist had reimagined Revere’s version of the Boston Massacre, which did not indicate race, and made Attucks the central figure. In the lithograph, Attucks is falling backward, his hand on the bayonet that has just pierced him.

Boston Massacre, March 5th, 1770, 1856 (AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY)

The visual parallels between Forman’s photograph and the print from more than a hundred years earlier are remarkable. In the aftermath of the assault on Landsmark, the connection to Crispus Attucks was not lost on writers. Editors at Ebony offered a blues verse:

If you see Crispus Attucks and the blacks who died to make us free

If you see Crispus Attucks and the blacks who died to make us free

Tell ’em it’s business as usual in Boston and the land of liberty.

The editors wondered “what Crispus Attucks, the black who became the first martyr of the Revolution and the hero of the Boston Massacre, would have thought of . . . [the assault on Landsmark]. He would have understood the racism, of course, for all or almost all of the white Founding Fathers were marked by the racism of their time. But it is doubtful he would have understood the insensitivity of public officials who are repeating the mistakes of the white Founding Fathers and subtly fanning the flames of discord with code words like ‘forced busing’ . . . Haven’t we learned in all these years that there can be no salvation for us, either in time or eternity, if we do not regain the sense and the spirit of the revolutionary dream proclaimed on July 4, 1776?”

A letter to the Boston Globe noted that “it is ironic that Mr. Landsmark was attacked within a stonethrow’s [sic] distance of the site of the Boston Massacre, where Crispus Attucks, a black man, was the first person to die in the American Revolution. Now, as evidenced by this attack, the black people of Boston have very little reason to celebrate the Bicentennial, for they still are not free to safely walk the streets of this city.”

Landsmark himself also suggested the connection. At a press conference held on April 7, 1976, he pointed out to a reporter, according to the black newspaper the Bay State Banner, “that he was struck in the face with an American flag in front of City Hall not far from Faneuil Hall (a so-called ‘cradle of liberty’ where the American Revolutionaries used to gather), during the Bicentennial year, at a location not far from the site ‘where Crispus Attucks . . . got his.’ ”

Paul Revere’s engraving of the Boston Massacre, Crispus Attucks, and the Revolutionary tradition are not the only deep context for reading The Soiling of Old Glory. Forman’s photograph also evoked visual and historical connections to another image forever tied to the story of freedom: Joe Rosenthal’s photograph of the flag raising on Mt. Suribachi on February 23, 1945. One writer to the Herald American thought that the photograph “of the young man lunging at the struggling Mr. Landsmark’s face with the steel-shafted American flag—this picture was historic. Doesn’t it remind you somehow of that oldie of the Marines raising the flag on Iwo Jima?”

Rosenthal’s photograph is probably the most famous and most widely reproduced image in history. It appeared in newspapers throughout the world, was used in a poster campaign for a War Loan Drive, was placed on a postage stamp, and served as the model for the Marine Corps War Memorial. It received the Pulitzer Prize. It also proved controversial. Throughout his life, Rosenthal was forced to defend its authenticity against accusations that he staged the scene.

Joe Rosenthal, born in 1911, became a newspaper photographer in the early 1930s. His poor eyesight kept him from enlisting as a soldier, but it did not prevent him from serving as a combat photographer for the Associated Press. He was always at the front line of the action, whether crossing the Atlantic in a convoy or diving with navy bombers. He was among the initial wave of marines who hit the beaches at Iwo Jima. He later discussed the impossibility of the situation. “No man who survived the beach can tell you how he did it,” Rosenthal recalled. “It was like walking through rain and not getting wet.”

The battle for Iwo Jima took thirty-six days and left more than twenty-five thousand American soldiers dead or wounded. On the fifth day, the marines reached the top of Mt. Suribachi, located on the southern end of the island. Rosenthal and his Speed Graphic camera were not far behind. On his way up the mountain on the morning of February 23, accompanied by two other journalists, Rosenthal encountered several marines on their way down. Lou Lowery, another photographer, said that the soldiers had already raised the flag. Indeed, Lowery had gotten the shot at around ten thirty. Rosenthal went to the peak anyhow. When he got there, there was a group of marines arranging a second flag raising. Bob Campbell, one of the photographers with Rosenthal, took a picture of the first flag coming down as the second went up.

Rosenthal backed up to get the picture of the second flag raising. Where he stood, he recalled, “the ground sloped down toward the center of the volcanic crater, and I found that the ground line was in my way. I put my Speed Graphic down and quickly piled up some stones and a Jap sandbag to raise me about two feet (I am only 5 feet 5 inches tall) and I picked up the camera and climbed up on the pile. I decided on a lens setting between f-8 and f-11, and set the speed at 1-400th of a second.” Bill Genaust, a marine photographer shooting motion picture footage, was next to Rosenthal and asked if he was in his way. Rosenthal said no, and as he answered, the men lifted the pole and he took the photograph.

He had no idea whether the picture was any good, and he also took a posed shot of all the marines together in front of the flag. This second picture, along with the fact of the two flag raisings, led a Time-Life correspondent to report that Rosenthal’s photo of the flag raising was staged. The reporter retracted the story, but the damage was done, and Rosenthal continually had to defend the photograph and retell the story of how it came to be.

One reason for the persistence of the accusation is the brilliance of the image. It is hard to believe that a photograph this perfect was not posed. The six men (yes, six; two stand behind) are united, their exertions a ballet of form and effort. Notice the bend in the right leg of each man. We do not see their faces, just their bodies and their hands. Their anonymity makes their effort that much more noble. The last soldier in the line is forever striving upward, forever trying to raise the flag, forever trying to close the gap between reach and reward. At their feet is the chaos of debris that contrasts with the serenity of the valley and horizon below. The powerful diagonal of the hundred-pound pole slashes across empty gray sky. The flag itself, mirroring the postures of the men, prepares to unfurl.

Joe Rosenthal, Flag Raising on Mt. Suribachi, 1945 (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

For a generation, Rosenthal’s photograph reigned as the ultimate symbol of American sacrifice and patriotism. Forman’s picture stood immediately as the antithesis to Rosenthal’s, an image that captured how far the United States had fallen since the heady days of 1945, a picture of national hatred that literally desecrated the achievement and memory of the men on Mt. Suribachi. Senator Edward Kennedy, for one, immediately made the connection. In the two years since busing had started, Kennedy had personally experienced the rage of the crowd that denounced him for his support of Judge Garrity and the court’s order. “There are two pictures in which the American flag has appeared that have made the most powerful impact on me,” he said. “The first was that of Iwo Jima in World War II. The second was that shown here in Massachusetts two weeks ago in which the American flag appeared to have been used in the attempted garroting of an individual solely on the basis of his color. That’s been obviously one of the most moving and shocking actions that any of us could imagine.”

It seemed as if one could write a history of the nation’s decline in the thirty-one years between photographs. Not merely the busing crisis but a general sense of malaise afflicted the country in the mid-1970s. Whatever economic and social progress had been made in the 1950s and ’60s seemed stalled. Americans suffered through Vietnam and they suffered through Watergate, two crises that raised fundamental questions about patriotism and the vitality of the nation. People felt lost, and into that sense of dislocation entered Forman’s shocking photograph that seemed to confirm the worst nightmares over the fate of the country.

It was not only a matter of patriotism but also one of faith. If visually The Soiling of Old Glory could be tied to the Revolutionary War and World War II, it could also be tied to religious images of crucifixion. The iconography of crucifixion, like that of Madonna and child, is so deeply embedded in the visual culture of the Western world that it sometimes seems as if any image can be made to fit the profile. In The Soiling of Old Glory, the religious symbolism is apparent. The assault occurred on April 5, during the Lenten season, and one writer to the Herald American reminded readers that “Easter is coming and with it, we are taught, hope and joy. May we dare hope that Mr. Landsmark and other innocent victims of similar unprovoked attacks search their hearts for charity towards those people and say ‘Forgive them Father, for they know not what they are doing.’ ”

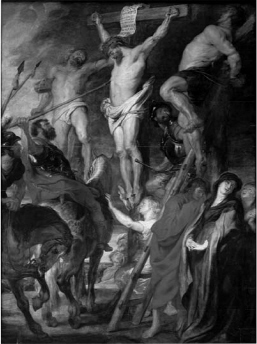

Landsmark’s outstretched arm and bent body evoke images of Christ on the cross. More specifically, Joseph Rakes’s use of the flag as a spear suggests the stabbing of Christ in the side by the Roman soldier Longinus, who afterward converted to Christianity and was canonized. Representations of the Crucifixion often included the piercing of Christ. One example should suffice to demonstrate how Forman’s photograph suggested the scene of the Crucifixion. Peter Paul Rubens, the Flemish artist, painted Christ on the Cross sometime around 1620. In the painting, Longinus, dressed in black, is about to drive the spear into Christ’s side. The space is tight and crowded. We read the painting from left to right, and we too, like the observer in the foreground right, wish to turn away in mourning for what we see.

Reading The Soiling of Old Glory in the light of Paul Revere’s engraving, Joe Rosenthal’s photograph, and Peter Paul Rubens’s painting deepens our understanding of Forman’s accomplishment and demonstrates why his photograph might be considered a visual masterpiece as much as a striking example of spot news journalism. The image comes into even sharper focus if we examine it in the context of the other pictures Forman took at the rally. Doing so provides a fuller portrait of the assault and reveals ways in which the photograph has been misread.

Peter Paul Rubens, Christ on the Cross, 1620 (VIAMSE MUSEA)

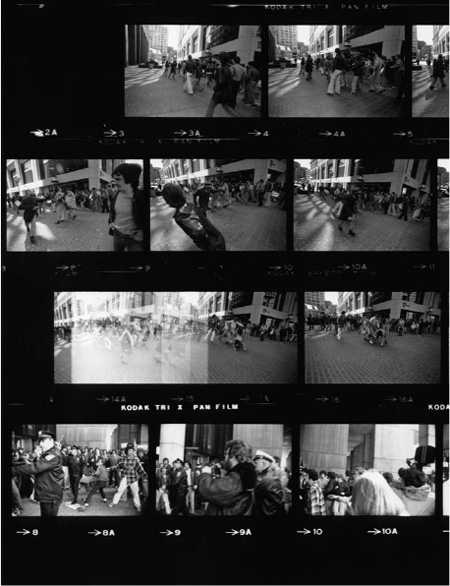

Forman took twenty-three pictures at the rally, seventeen with the 20 mm lens, all of which depict the assault, and six with the other camera that had the 35 mm lens. The first photograph, slightly out of focus, captures the assault just under way. Whatever expletives have been shouted echo in the air, and the protesters seem to descend on Landsmark and another black man, both of whom are in defensive postures. The youths circle, fists cocked. The flag bearer is to the side, with the other marchers.

Stanley Forman, contact sheet, 1976 (COURTESY STANLEY FORMAN)

With the second shot, Forman has found his focus. The confrontation has drawn the attention of all the spectators. Those who have already walked past look back. The flag holder has his eyes set on the scene. In the next shot, Landsmark recoils from an outstretched fist. All eyes are on the punch. The youth in leather jacket and white pants is preparing to attack. A boy to his side stands on his toes, straining to see the fight. Toward the rear, a man with coat and tie seems to be rushing toward the scene, but he is not racing in to break it up. He is a news photographer, caught in front of the procession, rushing back to try to get a picture.

In photographs four through seven, the assault continues. The student in white pants gets his blows in as Landsmark covers up. The boy who was on his toes now races in and kicks Landsmark. The other black man shields himself and moves away. The presence of the foreground youth, hands in pockets, would seem not to bode well for either man, but he cuts through the plane of Forman’s camera, and it looks for a moment as if both men will manage to flee the assault. But others are rushing in, as the next two photographs make clear. The boy in the plaid shirt has made his way back to Landsmark, followed by a student in a white jacket. The other victim will make his escape, but Landsmark is caught. The photographer in the rear is still out of range, camera in hand.

With the tenth shot, Forman felt the motor drive failing. The negative reveals problems with the film, and the next shots are double-exposed. Herald editors cropped out the double-exposed portion of one of these images and placed it on the front page below the assault with the flag. Between double-exposed and torn negatives there is a clear shot of the assault. This is an effective spot news photograph in its own right. The angle is low, giving the feeling of being on the ground and in the fray. The scene is open, a horizontal triangle of action in which the fallen Landsmark is at the pinnacle. To the left, the flag swirls into action. The figure who earlier had been in the foreground has moved to the far left, staying out of trouble. To the right, a mustachioed man in a windbreaker is the only figure in action, racing to the scene. In the background center left, a woman holds her hands to her face. She is reminiscent of the shawled woman in a similar location in Paul Revere’s print, modeling the viewer’s shock.

Forman switched to manual, and the very next shot made headlines. As the contact sheet makes clear, the original shot was cropped to create a more dramatic picture. The open space to the right alters the gravity of the image, making it feel less claustrophobic. The Herald American image is cropped on top and bottom as well, compressing the action and bringing into greater prominence the Old State House by reducing the building and sky behind. The wider panoramic view does not work nearly as well as the tight focus on the flag and Landsmark.

Ever since there have been negatives, documentary and news photographers have cropped the pictures they have taken. A well-cropped photograph eliminates unnecessary or irrelevant pictorial information, brings out the aesthetic value of the shot, and helps to focus the essential story. The practice is commonplace and bears comparison to quoting only the essential part of a speech. As long as the central meaning of the image or text is not altered, a cropped photograph is every bit as objective a document as an uncropped one, even though it undoubtedly alters the dimensions of the story presented to the viewer.

In many respects, the uncropped and cropped versions of The Soiling of Old Glory stand as a testimony to the effective use of the technique. At the same time, all photographs now carry with them some suspicion that they misrepresent reality. The anxiety developed alongside the form itself and grew out of the opposite assumption that governed ideas about photographs in the beginning. In the first half of the nineteenth century, viewers believed that daguerreotypes were perfect representations of objects in nature, providing exact depictions of what they recorded. These “sun pictures,” as they were sometimes called, were but “pencils of nature.” Many went so far as to believe that photographs captured not only external facts but internal truths as well. A portrait was said to reveal a person’s soul. Ralph Waldo Emerson, the philosopher of American individualism, agreed: “The Daguerreotype is good for its authenticity. No man quarrels with his shadow, nor will he with his miniature when the sun was the painter. Here is no interference, and the distortions are not blunders of an artist, but only those of motion, imperfect light, and the like.” Unfortunately for Emerson, he despaired over his appearance in daguerreotypes and lamented the “assinizing” effect the camera had on him.

Assumptions about the objectivity of photographs remain part of our belief system, long after photographers realized they were not simply machine operators but artists who simultaneously captured and manipulated the scene before them in both subtle and overt ways. Lewis Hine, whose portraits of workers shaped Progressive Era cries for social justice, said it best: “While photographs may not lie, liars may photograph. It becomes necessary then to see to it that the camera we depend on contracts no bad habits.” The worst habits of photographers, those that played off of viewers’ assumptions about photographs as documents of reality, involved directly manipulating the scene being photographed. One of the early examples of this transgression came during the Civil War when Alexander Gardner, eager to communicate to viewers a message about the war, moved a dead soldier at Gettysburg to a spot between some rocks, propped his rifle up, and took a picture titled Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter.

Overt acts of manipulation are unusual, and even subtle ones that involve actions other than photographic processes are not tolerated. For example, in 1936, Arthur Rothstein, a documentary photographer for the Farm Security Administration, found a cow’s skull in the badlands of South Dakota. The skull, resting atop parched, cracked earth, became a symbol of drought and depression. But it was soon discovered that Rothstein moved the skull some ten feet closer to the cactus for the purposes of composing a better image. Opponents of Roosevelt’s New Deal denounced Rothstein’s photograph as propaganda and used it to condemn FDR’s policies.

As viewers, we continue to bounce between the extremes of seeing photographs as objective representations of fact and seeing them as artistic constructions that create and interpret reality rather than record it. We will not tolerate overt acts of manipulation, nor should we. Composed and contrived photographs are lies that may get at some form of emotional truth but cannot serve the demands of documentary truth. At the same time, we tolerate certain photographic practices and techniques such as cropping or adjusting contrast, and we should. These techniques, as long as they do not alter the content of the image, are tools that make for a clearer, more focused photograph. The technique is not entirely innocent, and it does serve as an important reminder that the photographer is no neutral spectator. But when The Soiling of Old Glory was cropped, editors created a more powerful image, not one that distorted the truth of the moment.

It is possible, however, that an even deeper truth resides in the multiple-exposed image that immediately preceded the front page shot that went on to a win a Pulitzer Prize. That image captures the frenzy and uncertainty of the assault, the blur that was the event. The other images advance frame by frame; each is a tableau that we study before moving on to see what happens next. But in this picture, linearity gives way. The flag bearer is both racing in on the left and swinging the flag at the center. Landsmark is both being beaten to the ground and being lifted up. The picture matches the blurriness of the event, how it must have looked from the point of view of the victim: fist, flag, frenzy. And the multiple exposures provide something else as well: the tear in the negative reminds us that the technology of representation is inseparable from our understanding of the event itself, that a photographer is present. Here, then, is a pictorial truth that the camera can provide.

A question that remains in viewing The Soiling of Old Glory is whether our perception of what is taking place in the photograph accurately reflects what is indeed occurring. Photos deceive sometimes not because of the designs of the photographer but because the viewer does not have complete information. Take, for example, Alfred Stieglitz’s Steerage. Stieglitz was among the first to elevate photography to the realm of art. Steerage certainly stands as a striking modernist work, with lines and shapes and depths that suggest an artistic composition. The photograph is also a document, one that represents class distinctions and the plight of the immigrant at the turn of the twentieth century. For years, I thought of the photograph as a stunning depiction of the journey to Ellis Island. And then I learned that the ship on which Stieglitz took the picture was not arriving but leaving, bound for Europe. These poor and huddled masses are not seeking a new life in America but are returning home. The photograph remains a powerful image of migration, but any reading of the picture that does not consider the contextual fact that the ship is departing, not arriving, is fatally flawed.

Alfred Stieglitz, Steerage, 1907 (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

There is also the problem of sequence in considering photographic truth. The camera freezes time, giving us always a moment, a fraction of a narrative that stretches before and after the isolated instant. The question is whether the frozen moment tricks the eye, leading the viewer to one interpretation whereas another, or opposite, interpretation would be closer to the truth of the event. Consider the controversy over a photograph taken on 9/11 but not published until 2006 because of how disturbing it seemed.

On the morning of 9/11, Thomas Hoepker, an experienced photojournalist, crossed over from Manhattan into Queens and Brooklyn in an attempt to get closer to the scene of the catastrophe. He stopped his car in Williamsburg to shoot a group of young people sitting by the waterfront with the plume of smoke rising from across the river. He did not publish the shot at the time, feeling it was “ambiguous and confusing,” a pastoral scene of five youths chatting amicably as the towers burned.

David Friend included the image in Watching the World Change: The Stories Behind the Images of 9/11. In the book, Hoepker expresses his concern that the youths in the photograph “didn’t seem to care.” Seizing upon this, Frank Rich, in his column in the New York Times as the fifth anniversary approached, saw the photograph as a prescient symbol of indifference and amnesia. He characterized the New Yorkers as “enjoying the radiant late-summer sun and chatting away.” “The young people in Mr. Hoepker’s photo,” Rich wrote, “aren’t necessarily callous. They’re just American.”

Thomas Hoepker, Young People on the Brooklyn Waterfront, September 11, 2001 (MAGNUM PHOTOS)

David Plotz, of the online magazine Slate, would have none of this interpretation. “Those New Yorkers Weren’t Relaxing,” the headline argued. “The subjects,” Plotz observed, “have looked away from the towers for a moment not because they’re bored with 9/11, but because they’re citizens participating in the most important act in a democracy—civic debate.” Plotz argued that Rich took a “cheap shot” in exploiting as metaphor the image of citizens turning their backs on the conflagration, and he called for a response from any of the subjects.

Shortly thereafter, Walter Sipser wrote to Plotz: “It’s Me in That 9/11 Photo.” He said, “We were in a profound state of shock and disbelief, like everyone else we encountered that day.” Sipser denounced Hoepker for not trying to ascertain the state of mind of the photo’s subjects and for perpetuating a misinterpretation of a frozen moment.

Hoepker responded that “the image has touched many people exactly because it remains fuzzy and ambiguous in all its sun-drenched sharpness,” especially five years after the event. And he wondered: was the picture “just the devious lie of a snapshot, which ignored the seconds before and after I had clicked the shutter?”

“The devious lie of a snapshot” is a marvelous phrase. It is not the photographer who is devious but the nature of the snapshot itself, which isolates and freezes action, disconnecting it from context and sequence. More often than not, the single frame is true to the event as recorded in the frames that come before and after. But every so often, as in the case of Young People on the Brooklyn Waterfront, September 11, 2001, the single shot can distort our understanding of what is taking place. Such is the situation with The Soiling of Old Glory.

There are two ways in which The Soiling of Old Glory tricks the eye. The first concerns the flag. The day after the assault, the Globe reported that “news pictures indicated that the staff of an American flag was used in the attack.” It looks as if Rakes is taking dead aim at Landsmark’s body and is preparing to plunge the staff of the flag into him. But as the double-exposed previous picture makes clear, Rakes is swinging, not driving, the flag toward his victim. The Soiling of Old Glory freezes the flag in its movement from side to side, giving the impression that the flag bearer is thrusting Old Glory into Landsmark. In fact, the staff of the flag missed its victim, though early reports claimed that Landsmark had been hit by it. Knowing this takes little away from the power and meaning of the image—Landsmark was indeed assaulted with the American flag—but it does illustrate how a photograph can suggest a story that is not quite right.

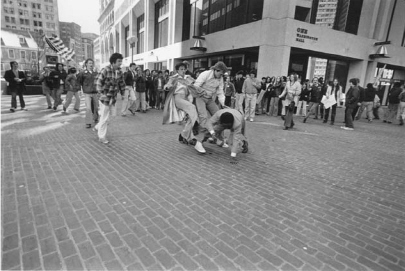

Perhaps more significant is the second way in which the photograph is misread. The man who, in a previous image, is in motion racing to the scene has arrived and is grabbing Landsmark. It would appear that he has joined the fray to get in his punches and, worse yet, is pinioning Landsmark’s arms so that the flag bearer has a clear line of attack. In fact, the person holding Landsmark is Jim Kelly, one of the adult organizers of the protest, and he has raced in not to bind Landsmark but to save him from further violence. Kelly was helping Landsmark to his feet—recall that he had been on all fours a few seconds before. As the president of the South Boston Information Center and a ringleader of the protests, Kelly felt responsible for the actions of the teenagers, and he dashed in to try to break up the fight. In another photograph taken a moment later (see facing page), he can be seen holding his arms out wide trying to keep the protesters back as Landsmark stumbles to safety.

Stanley Forman shooting the scene, 1976 (COURTESY STANLEY FORMAN)

Kelly was a vocal, visible, militant opponent of busing, but he did not condone violence. His effort to come to Landsmark’s aid is a noteworthy act, and our knowledge of it changes our understanding of the photograph. The assault on Landsmark was brutal and vicious, and Forman’s photograph captured the truth of the moment, the toxic cocktail of racial hatred and patriotic fervor that stunned Boston and the nation. It turns out it captured something else as well, only no one knew it at the time. A white man is coming to the aid of a black man. Perhaps there was some hope for Boston on the vexed subject of race. As it turns out, both Landsmark and Kelly would play key roles in shaping the future. As a photojournalist, Forman would too.

There is a picture of him taking the shot. An Associated Press photographer covering the incident has inadvertently caught Forman in the frame. Forman’s body is hunched and taut as he snaps away. Landsmark is trying to flee, but a student has hold of his coat and is preparing to punch him. Landsmark’s satchel lies by his feet on the ground. Rakes and the flag circle toward the victim in the background; Kelly moves toward him in the foreground. There is space for Landsmark to run, if only he can slip loose. He strains in the direction of Forman. Afterward, Landsmark would wonder why no one came to his aid. But Forman is there, with his finger on the shutter.