When Boston bid to host the 2004 Democratic National Convention, one of Mayor Thomas Menino’s goals was to change the perception of the city. “For too many people around the country,” he declared, “when they think of Boston the image they remember is of Ted Landsmark getting hit with an American flag. I wanted the opportunity to show people we are a much different city now, a city where diversity is welcome.” John Kerry, the Democratic nominee for president, had his own reasons to talk about the flag, and in his acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention in Boston in the summer of 2004, he waxed eloquent: “You see that flag up there. We call her Old Glory. The stars and stripes forever. I fought under that flag, as did so many of you here and all across our country . . . For us, that flag is the most powerful symbol of who we are and what we believe in. Our strength. Our diversity. Our love of country. All that makes America both great and good.”

The cult of the American flag of which Kerry spoke took root in the Civil War. The Continental Congress may have created the flag in 1777, and Francis Scott Key may have celebrated it in verse in 1814, but during the Civil War the flag transcended its status as a marker of sovereignty. It became a symbol of the meaning of the nation, and the cloth itself became cause for devotion.

A sermon delivered by Henry Ward Beecher in May 1861 set the tone for the new understanding. The son of Lyman Beecher, one of the leading evangelical ministers of the day, and the brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was outsold only by the Bible, Beecher had a national reputation as a fiery orator and proponent of social reform. His pulpit was the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, New York, and on this spring day he addressed two companies of the Brooklyn Fourteenth Regiment on “The National Flag.”

“A thoughtful mind,” Beecher observed, “when it sees a nation’s flag, sees not the flag, but the nation itself. And whatever may be its symbols, its insignia, he reads chiefly in the flag the government, the principles, the truths, the history, that belong to the nation that sets it forth.” He declared “this glorious National Flag” to be “the Flag of Liberty” and lamented that “this flag should, in our own nation, and by our own people, be spit upon, and trampled under foot.”

Beecher perhaps had not yet heard the appellation, but his use of glorious captured something in the air: the Civil War gave Old Glory its name. No less a writer than Nathaniel Hawthorne picked up on the new phrase. Hawthorne had returned to the United States in 1860, after several years’ absence. The outbreak of the war reinvigorated the fifty-seven-year-old novelist: following a tour of Washington and the surrounding area, he returned home to Concord and in April 1862 wrote “Chiefly About War-Matters” for the Atlantic Monthly. Hawthorne was no zealous Union man, and the dedication of his final book to his friend Franklin Pierce, the former Democratic president who during the war denounced the abolitionists, brought condemnation. In his essay, signed “A Peaceable Man,” Hawthorne analyzed “the anomaly of two allegiances,” the one to the State and the other to the Nation. The State was represented by “the altar and the hearth,” whereas the Nation “has no symbol but a flag.”

That flag, he observed, was everywhere: “The waters around Fortress Monroe were thronged with a gallant array of ships of war and transports, wearing the Union flag,—‘Old Glory,’ as I hear it called these days.” In their diaries and memoirs, Union soldiers also started using the phrase. In January 1862, David Day gazed on “ ‘old glory’ proudly waving over the frowning battlements at Fortress Monroe.” Two months later, George Smith noted that “when Old Glory crept up to the masthead in the morning and unfolded in the breeze he was greeted with the cannon’s roar.” In his memoir, George Sherman could not express his feelings as he returned north at the end of the war and “beheld in the distance ‘Old Glory’ as we had become accustomed to call it.”

Feelings for the flag were already running high when the New York Herald reported a scene that took place in Nashville in February 1862. Union soldiers had taken the city, and “an aged gentleman, a native of Salem, Massachusetts, and for twenty-eight years a citizen of Nashville, came through the crowd to the colonel and produced an American flag, thirty-eight by nineteen feet in size.” This was Captain William Driver, a retired New England sea captain. The flag that he provided had been given to him in 1824, a twenty-first-birthday present and a gift as he took command of the 110-ton brig Charles Doggett in Salem harbor. Legend has it that as the flag unfurled he remarked, “God bless you. I’ll call it ‘Old Glory.’ ”

Driver retired in 1837 from a career at sea that included making at least two trips around the world and taking the descendants of sailors who had mutinied on the Bounty in 1789 from Tahiti to Pitcairn Island. He settled in Nashville, to be near his brothers, and remarried after the death of his wife. Through it all, he was never without his flag, Old Glory, which he flew on all occasions.

When secession came, and Confederates tried to confiscate the flag, Driver had it updated (from twenty-four to thirty-four stars) and sewn inside a comforter. On February 25, the Sixth Ohio Regiment entered the city and hoisted a flag over the statehouse. Driver ran to retrieve his flag. He wrote to his daughter that he “carried our flag—Old Glory as we have been used to call it—to the Capitol and presented it to the Ohio Sixth. I hoisted it with my own hands on the Capitol over this proud city amid the heaven-stirring cheers of thousands.”

There is a flag in the Smithsonian that is said to be the original Old Glory. It has thirty-four stars and a small white anchor but is smaller than the flag reported in the newspaper in 1862. If the flag in the Smithsonian is indeed the original Old Glory, the provenance goes something like this: Driver, fearing that the winds would destroy Old Glory, substituted another flag the following day. In 1873, he gave Old Glory to his daughter, Mary Jane Driver Roland. In 1922, she presented the flag to President Warren G. Harding, who gave it to the Smithsonian Institution. A niece of Driver’s, Harriet Ruth Cooke, contested this history and claimed that she had been given the original Old Glory by her uncle. If so, its whereabouts are unknown. Finally, when the Sixth Ohio Regiment left, they took a flag with them. It was probably the replacement flag that Driver provided the following day. The soldiers placed it in one of the baggage wagons. We know what happened to that flag: famished mules made a meal of it.

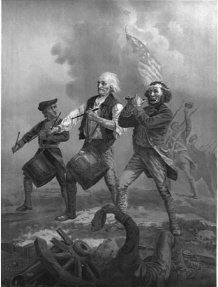

In the aftermath of the Civil War, the cult of the American flag intensified. Perhaps the most popular printed image of the last decades of the nineteenth century was Archibald Willard’s Yankee Doodle, later known as Spirit of ’76. Willard had served in the Eighty-sixth Ohio Volunteer Infantry during the war, and he began drawing military scenes. He developed a partnership with James Ryder, a photographer and businessman, and together the two did good business selling colored prints of Willard’s work. One of his most popular prints, titled Pluck, showed a group of boys being pulled in a wagon by a dog who takes off after a passing rabbit. Willard understood well the public’s preference for scenes that entertained and amused.

For the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Willard painted Yankee Doodle. His original intent was to do a humorous picture that poked fun at small-town celebrations and what had become the annual July 4 ritual of old-timers dressing up and reenacting the Revolutionary spirit. Willard tried his hand at this, but none of the sketches worked. Ryder thought the picture should be more sober, and Willard eliminated most of the humor. The portrait of the central figure of the elderly man with the drum was based on Willard’s father. The model for the fifer had served in the Civil War, and the drummer boy attended Brooks Military School in Cleveland.

The picture is well composed. Our eye goes immediately to the thirteen-star flag, upright between the center drummer and fifer. Of course, the flag, in a painting that came to be known as Spirit of ’76, is an anachronism, as it was not adopted until 1777. The boy looks to the elderly man. All three step forward in unison, leading a few soldiers who follow, one with a cap raised in apparent celebration. According to a piece Ryder published in 1895, viewers thought of the unit as three generations of one family who have stepped forward to reconstitute a broken line (the shattered cannon) and lead the troops toward victory. In the bottom right foreground, a fallen soldier doffs his cap to the flag as it passes by.

Archibald Willard, Spirit of ’76, 1876 (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

The original painting was displayed in the annex to Memorial Hall at the Philadelphia Exposition. One newspaper critic loathed the painting: “There is a great waste of good material here, and Mr. Willard’s work is rather oppressive.” But what the critics thought did not matter. For the public, the painting was a sensation, and Willard and Ryder couldn’t keep the chromolithograph in stock. Willard painted multiple versions, as was the custom with popular paintings. In a later rendering, the fallen soldier is sitting upright. Perhaps the depiction of a dying man saluting the flag as it passed created too much dissonance in viewers who wanted only to celebrate victory; he is cropped out entirely from the postage stamp issued by the United States Postal Service.

When Willard painted Spirit of ’76, calls for a day to honor the flag were in the air. As early as 1861, Charles Dudley Warner, editor and writer, called in the Hartford Press for making June 14, the day on which the flag resolution of 1777 was adopted, a national holiday. For the hundredth anniversary of that occasion, the New York Times lobbied for “a general display of the American flag throughout the country.” In the years that followed, cities and towns across most of the nation informally celebrated the centennial of the flag. In Philadelphia, five hundred school children received small flags. In Washington, the flag flew from all public buildings. Religious groups joined with secular to celebrate the flag. But not everyone reveled in the cult of the American flag. With the Civil War still fresh in their memory, southerners clung to their faith in the state, not the nation. An editor at the Richmond Dispatch thought that “patriotism must go deeper than the flying of the bunting.”

Nevertheless, starting in the 1880s, momentum began to build for the establishment of a national flag day. Convention has it that Bernard Cigrand, a Wisconsin teacher, first promoted the idea in 1885, and while Cigrand certainly published essays and editorials reminding readers of the importance of June 14, few Americans needed his coaxing to celebrate the day. Flag celebration seemed everywhere, and soon school superintendents and state governors issued proclamations of commemoration for the flag. By 1898, a writer for an evangelical newspaper lent support to celebrations of the flag, especially in the context of war with Spain, and pointed out that “June 14th has come to be largely considered by the patriotic citizens of this country as ‘Flag Day.’ ” So widespread was reverence for the flag, the Advocate of Peace offered readers a reminder that “there was a time when banners and flags . . . were unquestionably symbols of hatred, strife and war.” In an article called “Worship of the Flag,” the writer asked, “Is there no higher idea of a flag?’ and answered that flags must be transformed into symbols of peace: “As they have been made the means of unifying the national life in conquest and hatred and destruction, they must be made to serve as means of unifying it in the means of carrying out the deeper and noble purposes for which nations are called into being.”

The author’s dream of making the American flag “a flag of peace” did not come to pass, and with World War I the flag again traveled overseas in support of what Woodrow Wilson hoped would be a world “made safe for democracy.” Less than a year before asking for a declaration of war, President Wilson issued a presidential proclamation on May 30, 1916, that established June 14 as Flag Day. Several decades later, on August 3, 1949, in the aftermath of another war, President Harry S. Truman signed into law a congressional act designating a National Flag Day.

Even as the flag came to be venerated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it became subject to another kind of treatment: desecration. Of course, it makes perfect sense that the two might emerge side by side, an object worshipped and reviled, an icon and a target. Reports and pamphlets in support of legislation against federal flag desecration began to appear, primarily in response not to overt acts of destruction but to the commercial use of the image of the flag. Arguing that “old glory is too sacred a symbol to be misused by any party, creed, or faction,” one writer included a list of objects on which “old glory . . . is treated with grave disrespect or used for mercenary purposes.” The items ranged from pocket handkerchiefs and doormats to lemon wrappers and whiskey bottles. In 1890, the House Judiciary Committee recommended passage of a law that made it a misdemeanor to “use the national flag, either by printing, painting, or affixing said flag, or otherwise attaching to the same any advertisement for public display, or private gain.”

By 1898, the American Flag Association had been formed, and the anxiety over mistreatment of the flag had shifted from commercial misuse to physical destruction. “It should hardly be a question for argument whether a man may wantonly and maliciously tear our country’s flag to shreds or trample it into the mire,” claimed a petition to Congress submitted by the Milwaukee Daughters of the American Revolution. In speech after speech, Charles Kingsbury Miller, a retired Illinois newspaper executive, called for legislation protecting the flag, a “sacred jewel” that commanded “national reverence.” The social anxieties that animated Miller’s campaign included the fear of immigrants (“the multitude of uneducated foreigners who land upon our friendly shores”) and socialist anarchy (“the red flag of danger flies in America”). In response, state legislatures began to adopt flag-desecration statutes that prohibited using the flag for commercial purposes, placing any markings upon it, or publicly defacing or defiling the flag by words or actions.

These state laws were challenged in the courts by businesses that used the flag for advertising purposes and had been convicted and fined. In 1900, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled the state law unconstitutional on the grounds that it violated the Fourteenth Amendment provision that forbids states from abridging a citizen’s privileges and immunities. In 1907, the question of the constitutionality of a Nebraska law wound its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The law, passed in 1903, made it a misdemeanor “for anyone to sell, expose for sale, or have in possession for sale, any article of merchandise upon which shall have been printed or placed, for purposes of advertisement, a representation of the flag of the United States.” In Halter v. Nebraska, the plaintiffs, convicted under the state law of bottling beer with an image of the American flag on the label, appealed on the grounds that the statute infringed on their liberties as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

In an 8–1 decision, the Court upheld the Nebraska law. Justice John Marshall Harlan, whom history would honor for his vigorous dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)—“our Constitution is color-blind”— delivered the opinion. Guided by the constitutional principle that states have the power to legislate as long as the legislation does not manifestly violate the Constitution, Harlan held that the Nebraska law did not infringe upon any constitutionally protected rights. Where Congress has not legislated, the states still could. “By the statute in question,” Harlan ruled, “the state has in substance declared that no one subject to its jurisdiction shall use the flag for purposes of trade and traffic, a purpose wholly foreign to that for which it was provided by the nation. Such a use tends to degrade and cheapen the flag in the estimation of the people, as well as to defeat the object of maintaining it as an emblem of national power and national honor. And we cannot hold that any privilege of American citizenship or that any right of personal liberty is violated by a state enactment forbidding the flag to be used as an advertisement on a bottle of beer.”

In short order, uneasiness over the commercial exploitation of the flag subsided as American consumer culture accelerated. Of far greater concern were acts of defiling the flag, especially through burning. The tension between flag mania and flag protest reached one pinnacle during World War I. In June 1916, in New York, Bouck White, a Harvard-educated Congregational minister who fused Christianity and socialism in forming the Church of the Social Revolution, was convicted of burning an American flag that also bore the symbols of other nations. He was fined and sentenced to thirty days and told by the judge, “If ever was a time in this great Republic when every American should be true and loyal to the flag, it is now.”

As far as we know, none of those prosecuted for burning the flag as a protest against American involvement in World War I, or as an expression of political dissent, raised the issue that would certainly come to dominate discussion of flag desecration in the second half of the century: the First Amendment protection of free speech. The argument would not emerge until 1931, when the Supreme Court struck down state laws that originated in postwar fear of the spread of socialism in America. In the case Stromberg v. California, the appellant was charged with displaying a red flag in a public place “as a sign, symbol and emblem of opposition to organized government.” Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes overturned the state conviction primarily on the grounds that the statute was vaguely constructed. Hughes did not mention the First Amendment but rather the right of free speech found in the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The state has a legitimate interest in preventing “utterances which incite to violence and crime and threaten the overthrow of organized government,” but displaying a red flag is not such an utterance. In his dissent, Justice Pierce Butler said the Court was not called upon to decide whether the display of a flag constituted speech, but it was too late: what one did to or with a flag might be seen as a form of constitutionally protected expression.

To try to codify what was considered proper treatment of the flag, Franklin Roosevelt, in the midst of World War II, signed into law the Federal Flag Code. The code, approved on June 22, 1942, provided guidelines for the proper display and use of the flag. Section 4 of the code includes the admonitions that “no disrespect should be shown to the flag; . . . the flag should not be dipped to any person or thing; . . . the flag should never be carried flat or horizontally, but always aloft and free.” Section 7 of the code includes instructions on proper decorum during the Pledge of Allegiance.

The Flag Code was a guide for proper behavior. Penalties for failure to comply would have to come from legislative enactments, and the Supreme Court would play its role as the arbiter of constitutionality. In 1943, the Court heard the case of West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, which centered on the issue of compulsory flag salute in public schools. The appellees were Jehovah’s Witnesses whose religious beliefs did not permit them to salute any image or symbol, including the flag. In a 6–3 decision, the Court ruled that the state’s action violated the First and Fourteenth Amendments. Justice Robert H. Jackson’s majority opinion is remembered for his admonition that freedom means allowing dissent, especially in those areas that are most meaningful: “To believe that patriotism will not flourish if patriotic ceremonies are voluntary and spontaneous instead of a compulsory routine is to make an unflattering estimate of the appeal of our institutions to free minds. We can have intellectual individualism and the rich cultural diversities that we owe to exceptional minds only at the price of occasional eccentricity and abnormal attitudes. When they are so harmless to others or to the State as those we deal with here, the price is not too great. But freedom to differ is not limited to things that do not matter much. That would be a mere shadow of freedom. The test of its substance is the right to differ as to things that touch the heart of the existing order.”

The Court’s decisions in Halter, Stromberg, and West Virginia Board of Education would serve as precedent for the next string of flag-desecration cases. These would emerge out of the cultural strains of the 1960s, particularly student rebellions and opposition to American involvement in Vietnam. In ways that it had not previously, the American flag became an object of scorn and derision, yet also an object of hope enlisted in the cause of social change. It may seem inevitable that the flag would be burned and worn, waved and brandished, but for that to happen it had first to be demystified from a sacred emblem into something else, something more multivalent in meaning. That transformation first took root in cold-war America, and it was artists such as Jasper Johns and photographers such as Robert Frank who helped prepare the culture for the reexamination of America that was to come.

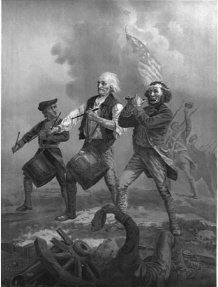

Born in 1930 and raised in the South, Jasper Johns, after service in the Korean War, settled in New York in 1953. In 1954–55, he painted Flag, and for years afterward Johns offered different versions of flags in different mediums. Johns also painted objects such as targets and numbers; his work marked a shift from abstract expressionism to the beginnings of pop art. He reclaimed everyday objects and compelled viewers to reimagine how they perceived “the things the mind already knows.” His first flag image, Johns said, came to him in a dream. The work he produced, while seeming to be merely a straightforward painted reproduction of the flag, on closer view consists of layers and depths. Johns used a technique that allowed the paint to dry quickly yet also reveal the brushstrokes. The work also contains elements of collage that bleed through the surface. The result is a work that looks quite different when viewed from a distance than when seen up close, a work that could be read as celebrating the flag while also raising questions about its composition and meaning. In the paintings that followed, Johns would bleach the flag of its colors, producing monochromatic white and gray flags, paint multicolored flags with ghost images below, and superimpose flags upon one another so that they seem to be coming toward the viewer.

Jasper Johns, Flag, 1954–55. Encaustic, oil, and collage on fabric mounted on plywood, 42 1 .4" ×60 5/8". Gift of Philip Johnson in honor of Alfred H. Barr, Jr. (106.1973). (THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK, NY)

In the 1950s, Johns was not the only artist inviting viewers to rethink the meaning of the flag and their relationship to the object. In 1955, Robert Frank, a Swiss-born photographer who had emigrated to the United States in 1947, won a Guggenheim Fellowship for a proposal to travel the United States and photograph the America he encountered. His various road trips took him all over the country, and he shot thousands of pictures from which he chose a few dozen for his book The Americans, published first in France, then in the United States in 1959. The book, with its stunningly original photographic vision of the country, a vision in which the photographer seems willing to convey his feelings to the viewer, is a masterpiece of the ongoing attempt to come to terms with the meaning of America. Indeed, Jack Kerouac wrote the introduction to the book. Kerouac, whose seminal On the Road appeared in 1957, said that Frank had “sucked a sad, sweet poem out of America.”

Frank’s book opens with Parade—Hoboken, New Jersey. We are looking up at a building. Two figures in windows across from one another, separated by several feet of brick wall, are looking out. We can tell both are women, but the face of the figure on the left is in the shadow cast by a bright white shade. The head of the figure on the right cannot be seen at all. We only see her left hand going to her mouth. The bottom of a rippling American flag cuts off everything above. As one commentator notes, “The flag . . . is a kind of guillotine.” Frank’s photograph plays on light and texture. This would appear to be no celebratory depiction of American patriotism. The flag seems suspended in air, attached to no pole or visible wire. The two spectators are trapped, dismembered witnesses to a parade.

Robert Frank, Parade—Hoboken, New Jersey, 1955–56: copyright Robert Frank, from The Americans (PACE/MACGILL GALLERY)

Robert Frank’s seemingly bleak assessment of America was part of a more general reevaluation of the meaning of the nation. In his poem “America” (1956), Allen Ginsberg declared:

America I’ve given you all and now I’m nothing.

America two dollars and twenty-seven cents January 17, 1956.

I can’t stand my own mind.

America when will we end the human war?

Go fuck yourself with your atom bomb

I don’t feel good don’t bother me.

I won’t write my poem till I’m in my right mind.

The meaning of America and the meaning of the flag went together. As the counterculture of the late 1950s and the 1960s came into prominence, attempts to redefine America often meant desacralizing the flag by wearing it. The cultural rebellions of the 1960s necessarily implicated the flag. Ginsberg came to sport a top hat with the American flag motif. In discussing Ken Kesey, the Merry Pranksters, and the drug culture of the 1960s, Ginsberg argued that “they didn’t reject the American flag but instead washed it and took it back from the neoconservatives and right wingers and war hawks who were wrapping themselves in the flag, so Kesey painted the flag on his sneakers and had a little flag in his teeth filling.” In 1969, the film Easy Rider featured Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper on a road trip in search of themselves and the nation. In the film, Fonda is known as Captain America, and he sports an American flag helmet and motorcycle. Their search ends tragically as they encounter an America intolerant of difference.

If for some the flag became a symbol of what was wrong with America, an ironic symbol to be reappropriated in different ways, for others it was a symbol to be enlisted in the cause of making the nation a more just and democratic place. One of the striking, and shrewd, tactics of the civil rights movement for racial equality was for marchers and protesters to enlist the American flag in their struggle. Until the 1960s, the flag, given the history of racial oppression and segregation, was not a symbol that African Americans embraced. Henry McNeal Turner, bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, spoke for many at the turn of the twentieth century when he declared, “to the Negro the American flag is a dirty and contemptible rag.” When Kenneth Clark, the distinguished psychologist whose work played a key role in the decision of Brown v. Board of Education, focused his attention on Harlem in the early 1960s, he encountered a man in his mid-thirties whom he quoted in his study Dark Ghetto: “The flag here in America is for the white man. The blue is for justice; the fifty white stars you see in the blue are for the fifty white states; and the white you see in it is the White House. It represents white folks. The red in it is the white man’s blood—he doesn’t even respect your blood, that’s why he will lynch you, hang you, barbecue you, and fry you.”

It is difficult to date with precision when civil rights activists realized that they needed to enlist the flag in their cause if ever they were going to feel represented by it. One key, early moment came in 1963 after Medgar Evers’s assassination. Evers worked tirelessly in Mississippi in support of desegregation and voting rights. He led a boycott of white merchants in Jackson and, as field secretary for the NAACP, helped establish chapters across the state. He was gunned down outside his home on June 12, 1963. Two days later, on Flag Day, women and children marched through Jackson carrying small American flags. The idea had originated only weeks earlier with Evers himself. A World War II veteran, Evers watched time and again as the police smashed the signs of protesters. If they carried flags, perhaps the whole calculus of protest would shift.

On May 31, some six hundred students had marched down Capitol Street, “singing and waving American flags.” The police took little mercy on them, grabbing the flags and beating the marchers. Two weeks later, Evers was dead. As protesters marched carrying small American flags, reporters could not believe what they witnessed— and photographed: the police used clubs against women and children with flags.

Thereafter, the flag became ubiquitous at civil rights marches, as images of the Selma to Montgomery March in 1965 make clear. After enduring a terrible beating when they first tried to march on behalf of voting rights, activists arrived in Montgomery and assembled in front of the Alabama state capitol. Charles Moore, a photographer for Life, documented the march. Moore, born in Alabama in 1931, had already distinguished himself for his exclusive photos from inside the administration building at the University of Mississippi, where James Meredith tried to enroll in 1962, and his searing photographs from Birmingham in 1963, when police used water hoses and dogs to attack protesters. At Montgomery, Moore found a spot facing the marchers, and he took a picture of the crowd. Hundreds of marchers, black and white, are pressed together. They carry and wave the American flag, dozens of which fill the air. They would hear Martin Luther King declare that “segregation is on its deathbed” and that “there never was a moment in American history more honorable and more inspiring than the pilgrimage of clergymen and laymen of every race and faith pouring into Selma to face danger at the side of its embattled Negroes.”

Another photograph from the Selma to Montgomery March captured one man’s embrace of the flag. James Karales was a staff photographer for Look. A 1955 graduate of Ohio University, he had served as an assistant to the distinguished magazine photographer W. Eugene Smith. In the image, the flag swirls around the shoulders of the marcher: it is his cape, his crown, or, potentially, his winding sheet. The youth’s face is serious, focused. The sunshine hits his eyes, a white stripe across his face, but he stares intently ahead. The stripes of his shirt mirror the stripes of the flag. His hand rests beneath the fabric, holding it aloft on a simple wooden pole. The flag is his comfort and his hope. He, along with other civil rights activists, had appropriated Old Glory to the cause and enlisted it on the side of justice.

Charles Moore, Alabama, 1965 (BLACK STAR)

If the fight for equality led African Americans to embrace the flag, opposition by intransigent southerners could lead civil rights proponents to burn it. On the afternoon of June 6, 1966, in Brooklyn, New York, Sydney Street, a middle-aged bus driver and a World War II veteran, heard on the radio that James Meredith had been shot in Mississippi, a day after embarking on a “march against fear” to encourage blacks to vote. Street took from his drawer his folded forty-eight-star American flag and carried it to a major intersection near his home. He set the flag on fire and dropped it to the pavement, where it lay burning. A few dozen people gathered, and an approaching police officer heard Street say, “If they let that happen to Meredith, we don’t need an American flag.”

James Karales, Selma to Montgomery Civil Rights March, 1965 (ESTATE OF JAMES KARALES)

Meredith would recover from his wounds and rejoin the march at the end of June. Meanwhile, on Flag Day, in Granada, Mississippi, marchers placed an American flag on a Confederate monument. In New York, Street was charged with a misdemeanor and given a suspended sentence. His appeal found its way to the Supreme Court, where a split Court reversed the conviction on the grounds that it wasn’t clear whether Street was convicted solely for burning the flag or for his speech as well. The decision did not protect flag burning as a form of speech; it only reaffirmed that words used against the flag were constitutionally protected.

By the time the Court decided Street in 1969, flag burning had become something of an epidemic. Across the country, protesters against the Vietnam War expressed their opposition by burning the American flag. These incidents reached a peak in 1967 when, at an anti-war rally in New York’s Central Park, a protester burned the flag and cameras recorded the event. Paul Krassner, founder of the Realist, a satirical countercultural magazine published from 1958 to 1974, and one of the cofounders of the Yippies, recalled that “in April 1967, at an anti-war rally in Central Park, I observed a hippie wandering around with a loaf of whole grain bread, looking for others to share it with, when he was approached by somebody with an American flag in one hand and a can of lighter fluid in the other. ‘Would you hold this?’ he asked. The hippie held the flag while the stranger set it on fire.” Within weeks the House Judiciary Committee convened hearings, and Congress debated passage of a bill that made it a criminal offense to “cast contempt upon any flag of the United States.”

Photographs of the Central Park flag burning especially roiled members of Congress, who repeatedly made reference to the images during the debate. Basil Whitener of North Carolina averred that “of all the photographs which I have seen in my lifetime, I have never been as immediately and as heavily repulsed.” Richard Poff of Virginia said the photographs “pictured the flag in a posture of obscenity.” Jerry Pettis of California reminded the chamber that “nothing has sickened the American people so thoroughly as accounts and pictures of unwashed, irreverent gangs burning and otherwise desecrating Old Glory.” And Dan Kuykendall of Tennessee asked rhetorically, “Which is the greater contribution to the security of freedom: the inspiring photo of the marines raising the flag on a bloody hill at Iwo Jima, or the shameful pictures of unshaven beatniks burning that same flag in Central Park in New York?”

Not everyone embraced the bill. Congressmen such as John Conyers of Michigan and Don Edwards of California raised questions about its constitutionality and advisability. “This legislation,” they argued, “would infringe upon what is certainly one of the most basic of freedoms, the freedom of dissent.” Conyers and Edwards were two of only sixteen who voted against the bill, which passed in the House with 387 voting yes (thirty did not vote). It sailed through the Senate as well, and in 1968 the first Federal Flag Desecration law went into effect. Any person found guilty of “publicly mutilating, defacing, defiling, burning or trampling” the flag faced a thousand-dollar fine and/or up to a year in prison.

At the very moment that the burning of the flag as a protest against the Vietnam War gained national attention, the flag also began to appear as an object used and depicted by artists as an object of scorn. In 1967, a New York art gallery owner, Stephen Radich, exhibited sixteen anti-war paintings and sculptures by Marc Morrell. The window display on the second floor showed a flag stuffed to resemble a cadaver and hanging from chains. Among the works inside the gallery was an erect phallus covered with a flag. Radich was arrested and convicted of violating a New York flag-desecration law.

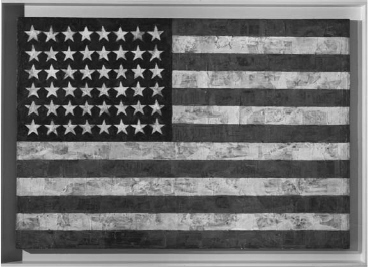

Artists continued to employ the flag in their work to protest not only the war but also civil injustice. In 1967, Faith Ringgold painted The Flag Is Bleeding. The 72"×96" canvas depicts a black man, a white woman, and a white man, standing with arms interlocked beneath the red and white stripes. The black man has been stabbed in the heart (or has stabbed himself; he holds what appears to be a knife in his left hand), and his blood drips upon the flag. In 1971, Wayne Eagleboy painted We the People, a work that depicts two Indians behind barbed wire that serves as the stars of the flag; the painting is framed in fur. In response to the arrest and conviction of Radich, artists in 1970 contributed to a People’s Flag Show at the Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village. The text for a poster for the show read: “The American people are the only people who can interpret the American Flag. A flag which does not belong to the people to do with as they see fit should be burned and forgotten. Artists, workers, students, women, third world peoples—you are oppressed—what does the flag mean to you? Join the people’s answer to the repressive US government and state laws restricting our use and display of the flag.”

Authorities shut down the show after the opening night, but among the works displayed was Kate Millett’s sculpture The American Dream Goes to Pot. The piece shows an American flag stuffed into a toilet housed inside a wooden cage. Millett, best known for her feminist work, recalls: “We were expressing our solidarity with our fellow artist and our right to use the flag as a sort of symbolic language of our dislike of the policy of the war in Vietnam.” By then, even Jasper Johns had created a flag image that was explicitly political. For Moratorium Day in 1969, a day for mass demonstrations against the Vietnam War, Johns contributed a silk screen that became the poster for the event. It depicts a sickly flag, not in red, white, and blue, but in green, black, and orange, a flag that perhaps evokes the jungles of Vietnam. At the center of the flag is a single white dot—a bullet hole.

In the late 1960s, Americans were burning and redesigning the flag, and they were wearing it as well. In April 1968, Hair opened on Broadway, and during one musical number the flag is used to clothe a naked body. When the show came to Boston two years later, the head of the entertainment licensing bureau opined that anyone “who abuses the American flag should be horse whipped in public on Boston Common.” In October 1968, Abbie Hoffman, one of the leaders of the Yippies, wore an American flag shirt to protest a hearing by the House Un-American Activities Committee. He was arrested and harrassed. At his trial he said, “I wore the shirt to show that we were in the tradition of the founding fathers of this country,” and when found guilty he declared, “I only regret that I have but one shirt to give for my country.”

Faith Ringgold, The American People Series, #18, The Flag Is Bleeding, 1967 (COURTESY FAITH RINGGOLD)

Dismayed and disgruntled by what they saw as the abuse of the flag, a very different group of Americans, construction workers, rioted on May 8, 1970. Wearing flag decals on their hard hats, and waving Old Glory in the air, they marched to Wall Street to break up a student anti-war demonstration. The construction workers started beating the protesters. According to one youth, “We came here to express our sympathy for those killed at Kent State and they attacked us with lead pipes wrapped in American flags.” From Wall Street, where they placed American flags on the statue of George Washington, the hard hats marched to City Hall, where they successfully demanded that the flag, flying at half mast to honor the four students killed in Ohio four days earlier, be raised. Those who protested the war and those who defended it, those who thought the flag was being defiled by the policies of the United States government and those who thought that to defile the flag was to be a traitor, now came adorned in red, white, and blue.

The question of the constitutionality of wearing the flag reached the Supreme Court from a case that originated in Massachusetts. In January 1970, two police officers in Leominster spotted a young man named Goguen with a 4" × 6" cloth version of the American flag sewn to his pants. When officers approached the youth, Goguen’s friends laughed. A complaint was sworn out against him for violating the contempt provision of the Massachusetts flag statute that begins “Whoever publicly mutilates, tramples upon, defaces or treats contemptuously the flag of the United States.” A jury found Goguen guilty, and the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court affirmed the decision. The district court overturned the conviction, finding the language of the contempt portion of the statute unconstitutional. The Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court, in a 6–3 decision in Smith v. Goguen (1974), agreed. Justice Lewis Powell argued that “in a time of widely varying attitudes and tastes for displaying something as ubiquitous as the United States flag or representations of it, it could hardly be the purpose of the Massachusetts Legislature to make criminal every informal use of the flag. The statutory language under which Goguen was charged, however, fails to draw reasonably clear lines between the kinds of nonceremonial treatment that are criminal and those that are not. Due process requires that ‘all be informed as to what the State commands or forbids’ . . . Given today’s tendencies to treat the flag unceremoniously, these notice standards are not satisfied here.”

Three months after Smith v. Goguen, the Supreme Court would decide one more major flag case. In Spence v. Washington, the appellant, a college student, was appealing his conviction under an “improper use” statute for flying an American flag, with the peace symbol taped to it, upside down from his apartment. The Court, in a 6–3 decision, overturned the conviction as a clear “case of prosecution for the expression of an idea through activity.” Spence had every right to use his private property in a peaceful way to express his beliefs, in this case protesting the killings at Kent State and American involvement overseas. The activity was a form of communication protected by the First Amendment. In his dissent, Justice William Rehnquist thought the state had the power to withdraw “a unique national symbol from the roster of materials that may be used as a background for communications.”

The tension between communication and desecration polarized the Court, and most Americans, on different sides of the debate. On July 6, 1970, Time magazine placed the “Fight over the Flag” on its cover and observed that “what was once an easy, automatic rite of patriotism has become in many cases a considered political act, burdened with overtones and conflicting meanings greater than Old Glory was ever meant to bear. In the tug of war for the nation’s will and soul, the flag has somehow become the symbolic rope.”

Through the 1960s and into the 1970s, the flag had been displayed, waved, erected, decaled, flushed, torn, and burned. And then came Forman’s photograph of Rakes using the flag as a weapon to assault a black man. For all the trampling, defacing, defiling, and mutilating that had been witnessed, this act seemed unimaginable, an act of desecration that slashed the fabric of the nation. One letter printed in the Globe no doubt spoke for many. Referring to the photograph, the writer “felt horror and repugnance at the desecration of our symbol of freedom and liberty.” Several days after the assault, David Wilson, a Globe columnist, began by referring to the conviction of Goguen, which drew the applause of “professional patriots.” “One cannot help wondering,” he continued, “whether those same professional patriots regard as desecration and subversion the use of the flagstaff streaming Old Glory to bash the face of a lawyer set upon by a mob while pursuing his lawful calling outside City Hall.” Wilson denounced all “those patriotic societies and organizations presumably devoted to preventing the misuse” of the flag for their “thunderous silence.” He implored these very groups, who he thought were probably conservative on the question of busing, to “be the first to express outrage.” Wilson took a global view of the incident and wondered about its impact abroad: “It is difficult to imagine a dramatic scenario with more poisonous consequences for American influence and, yes, national security, than the repulsive and nauseating spectacle of white hoodlums ganging up on a black man, and beating on him with the national emblem of the ‘land of the free and home of the brave.’ In distant places, Americans labor mightily against formidable adversaries and great odds to try to explain to citizens of other countries that America is not an oppressive, racist, and evil place.”

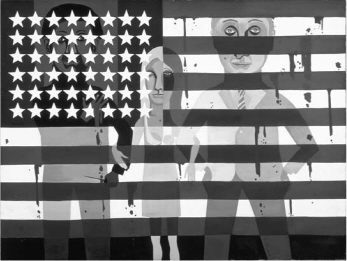

Robert Mapplethorpe, American Flag, 1977 (THE ROBERT MAPPLETHORPEFOUNDATION)

Within weeks of the incident at City Hall Plaza, most Bostonians and most other Americans would turn their attention to celebrating the Bicentennial of a nation they viewed as a free, democratic, and beneficent place. The image of the flag appeared everywhere: on cups, plates, mugs, clocks, cufflinks, magnets, ashtrays, snow-domes, pens, pillowcases, T-shirts, bikinis, even toilet paper. “I see no harm in these Bicentennial products,” said a member of the Sons of the American Revolution. “There is no harm in making a buck.” Others took a less sanguine view. One historian labeled the entire enterprise “Bicentennial Schlock,” a crass, commercial extravaganza that further sullied the meaning of the American Revolution.

The following year, Robert Mapplethorpe, who was at the beginning of his photographic career, took a picture of the American flag that serves as a coda to the era. In the Polaroid image, a tattered flag on a vertical pole waves across a soupy sky. The sun burns from behind the flag’s stars, a bulb of light ready to ignite the fabric. Threadbare and torn, the flag sways, but its days are numbered and it hangs beyond repair.