When, in 1882, Lieutenant-General Sir Garnet Wolseley led a British military expedition to Egypt, fought and deposed the dictator Arabi Pasha and restored the country to the Khedive, it foreshadowed events of exactly one hundred years later when a British task force went out to the Falkland Islands, conquered the troops of an Argentinian dictator, Galtieri, and returned the islands to British sovereignty. Separated by a century, both armies left with emotional dockside farewells, and returned to Victory processions through London and public investitures by their respective Queens - all in best Victorian style.

The Egyptian War of 1882 and the South Atlantic Campaign of 1982 have much in common and bear some remarkable similarities, not the least being that, from the moment of landing until the cessation of hostilities, both lasted exactly 4½ weeks. Both stretched the resources of the British Army, causing each expedition to be formed of ‘crack’ Regular regiments not normally used for such purposes.

Somewhat bitterly, and in a markedly ironic tone, The London Illustrated News (July 1882) commented upon this in a leading article:

‘England as a Great Power. Of course, we are incontestably one of the Great Powers, and yet it is pretty certain that Spain, which would like to have been present at the Constantinople Conference, but was shy of asking for fear of a rebuff, could more easily spare a respectable military contingent for foreign service than we can. Of course, we are a Great Power, and we are actually going to strengthen the Mediterranean Fleet by sending out a thousand Marines. A thousand Marines! Think of that Arabi, and tremble in your sandals. There is talk too of bringing Sepoys from India, should fighting appear likely, and precedents are being industriously cited to justify such a course. Yes, England is a Great Power, but it is a fact, sad or auspicious, according to whether it is regarded from the Jingo or the Wilfred Lawson point of view, that England has very few soldiers to spare. Half our Regular Army of 190,000 men is in India and the colonies, and the lion’s share of the remainder is in Ireland. Says the United Services Gazette, “We could not, without the undue strain of calling up our Reserves, muster more than 16,500 men of all arms for active service, and of this force a further contingent will be required to prevent Ireland from taking advantage of our embarrassment. England could not place more than 15,000 men in the field without denuding her colonies, and leaving her magazines and arsenals unprotected from those desperadoes who deal in dynamite.” Our contemporary recommends the addition of 10,000 men to the Royal Irish Constabulary, so as to relieve an equivalent body of troops. In case blows should be exchanged, it is lucky for us, seeing that as regards military force we are such a Lilliputian Great Power, that the Turkish officers, who had practical trial of Egyptian troops during the late war with Russia, have no very exalted opinion of them.’

Strikes a familiar modern chord, doesn’t it?

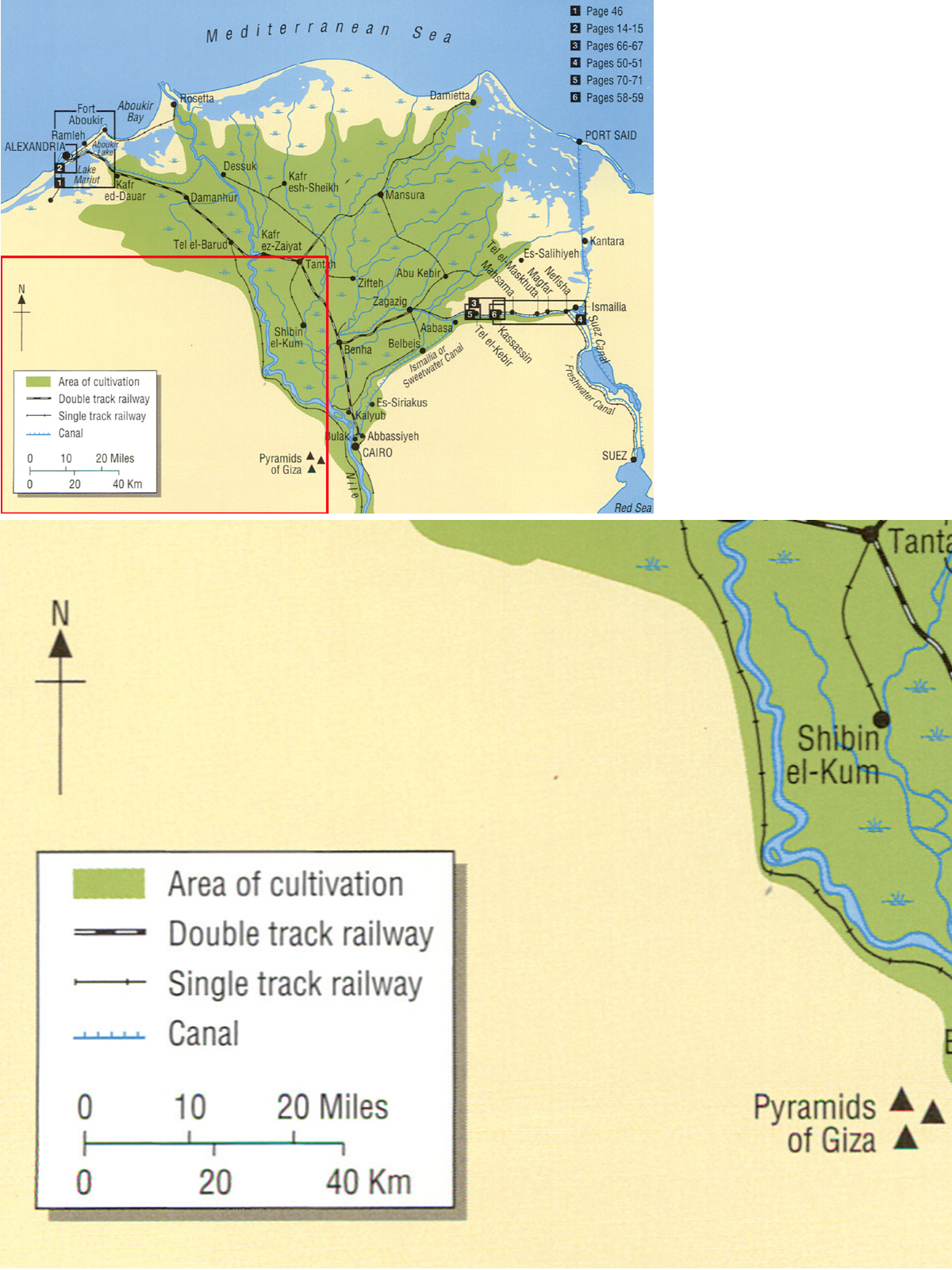

It began in 1862, when the Khedive Ismail came to the throne of Egypt and immediately embarked upon a programme of public works and improvements with complete disregard of cost. Building railways, harbours, telegraph systems and many other modern amenities, he transformed Alexandria and Cairo while greatly improving the country’s agriculture and commerce. But these brilliant achievements bankrupted and ruined the State, oppressing the people with an insupportable burden, until bond-holders and creditors began to be alarmed about the capacity of the Treasury to provide the huge sums required for interest. Money provided by European capitalists had to be repaid through charges on the country’s revenue, which itself depended upon the Egyptian Government’s direction of its own transactions. The Nationalists accused the Khedive of ‘pawning’ his country through being forced to accept European direction of its affairs.

As creditor for a great proportion of Egypt’s debts and with more extensive commercial relations than those enjoyed by other countries, England inevitably played a prominent part in the direction of Egyptian affairs. On top of that, seeing the Suez Canal as an essential highway to India, in 1875 Great Britain had emphasized its presence by acquiring nine-twentieths of the shares in the waterway. Subsequent concessions made by the Khedive in 1878 amounted to almost complete surrender, arousing belief that British and French influence would so guide Egyptian counsels that the country’s involved finances would be put straight.

But this obvious European domination, supported by the Egyptian Prime Minister, and the sudden dismissal of numerous Egyptian Army officers and Civil Servants, caused demonstrations and serious riots. The Khedive, aware that his own Prime Minister and the British Minister of Finance in Egypt were determined to reduce him to a mere figurehead, came into active opposition to the government that had been forced upon him. In June 1879 the diplomatic representatives of Britain and France jointly advised the Khedive to abdicate in favour of his son Tewfik; at which the Sultan of Turkey, who held sovereignty over Egypt, deposed Ismail and replaced him by Tewfik. The former Khedive, with sons Hussein and Hassan, his harem and a large suite, embarked for Naples, and his 27-year-old successor took over the Government.

Tewfik Pasha, Khedive of Egypt during the time of the Arabi rebellion. Coming to power in 1879, when Britain and France had advised his father to abdicate in his favour, he found himself unable to stand up to Arabi and his followers, but subsequent events in Egypt up to and including Kitchener’s Omdurman campaign of 1896-8 allowed him maintain his position in Egypt.

The new Khedive began with an honesty of purpose, and by 1881 his genuine attempts at reform indicated promise of progress, but he lacked the authority of will to tackle undeniable grievances among his military leaders. Precipitated by ill-feeling between Arab and Circassian officers, the army mutinied in mid 1881, under the leadership of Arabi Bey (Said Ahmed Arabi), a middle-aged man of tall stature, exceptional eloquence and a somewhat imposing presence. He had joined the army while still a boy, and was a recognized leader among his fellows even before his promotion from private soldier to commissioned rank. His persistent agitation and insubordination caused him to be cashiered, but he was soon reinstated by the Khedive, and was promoted to the colonelcy of a regiment. It soon became evident that Arabi had the charisma to be the natural leader of the lower ranks while at the same time representing the temper of the majority of the officers. In September 1881 a military revolt led to a confrontation before the Royal Palace in Cairo, between the Khedive and a group of Arabi-led Colonels; subsequently their demands led to Arabi’s appointment as Minister of War early in 1882.

Since the very inception of formed armies, soldiers have shown that they will do anything for a commander who shows self-reliance, decision and strength of mind – and it was these qualities that account for Arabi’s great influence over his countrymen. Unwavering, he boldly pursued his objective, entirely regardless of obstacles, and in defiance of those European nations hitherto regarded as the arbiters of Egyptian destinies. At the time of the outbreak of war, Arabi had achieved unqualified success – he had forced the Khedive to keep him at the head of affairs; he had endeavoured to wrest internal power from the hands of Europeans, only to see the balance restored by the aggressive action of the British fleet. At that time he was not only countenanced by the Sultan of Turkey, who was both his spiritual and secular leader, but that same ruler had bestowed upon him one of the highest Ottoman decorations – at a time when the ambassadors of the great European powers were taking counsel together in Constantinople as to the best means of overthrowing him!

The rise of Arabi alarmed both British and French Governments, who jointly addressed a Note to the Khedive, informing him of each country’s intention to, ‘ward off by united efforts all causes of internal or external complications which might menace the regime established in Egypt’. This meant, of course, that both countries intended to maintain their joint control for the good of Egypt, the peace of Europe, and the benefit of Egypt’s European bond-holders and creditors. Both Governments puzzled over an effectual type of intervention should Egypt tumble into anarchy – England had strong objections to occupying Egypt by itself as it would create opposition in that country and in Turkey, besides exciting the suspicion and jealousy of European powers, possibly leading to demonstrations and serious complications. A joint occupation was not a happy solution, so perhaps the least objectionable course might be a temporary Turkish occupation – under proper guarantees and controls.

During the next few weeks the matter was given a good airing in the British press and the public awaited events with interest. During this period a temporary understanding between the Khedive and his Minister of War appeared to cool the situation and, in March 1882, Arabi was made a Pasha. He immediately assumed the role of dictator, while the Khedive made futile endeavours to contest his activities. London newspapers talked of ‘the grave political anxieties… and the dubious position of the Khedive’s government’. In early April a plot against Arabi’s life was discovered, planned by Circassian officers in the Egyptian Army who were arrested and court-martialled, receiving the severest sentences. Early in May Arabi’s followers were infuriated when the Khedive commuted these to mere exile. Arabi’s inflamed supporters uttered wild threats, including a general massacre of foreigners in Egypt.

Yet only a week later the British press was displaying a surprising optimism, stating: ‘… the Egyptian crisis is over… British and French naval squadrons are in readiness at Suda Bay in Crete, but there is no immediate intention of landing troops in Egypt. But a week later it was reported that the British Naval squadron had moved to Alexandria, ‘as it is considered that the crisis is at its most critical point’.

There were reports that Arabi was emplacing guns at Alexandria and Damietta, and that he had ‘laid torpedoes’. During the next few weeks it was reported that the Egyptian populace were being stirred-up by foreign interference, and that a crusade was being preached against foreigners, particularly Europeans. On 17 June the situation boiled over and rioting was reported in Alexandria, some Europeans being killed in wild attacks directed at foreigners and their properties. Eventually Egyptian troops entered the city to quell the rioting and restore order; foreigners were advised to leave, but there was a shortage of shipping for a mass evacuation.

Arabi Pasha, the Egyptian Minister for War, leader of the Nationalist Party, and commander of the Egyptian forces during the war of 1882.

In Britain the Press reported that the new Egyptian leaders were hostile to Britain and France, and that their appointments merely placed Arabi in a stronger position, able to excite disturbances that threatened every European settled in Egypt; Arabi was a troublesome conspirator and order in Egypt could never be restored until he was removed from office.

Melodramas need a villain and over the centuries British wars have spawned a notable selection – Hitler, the Kaiser, Napoleon, Cronje, the Mahdi and the Khalifa, Cetewayo, Tippoo Sahib, the Rani of Jhansi, and in 1982 the Argentian Galtieri, and his counterpart a century earlier – Arabi Pasha, the Egyptian Minister of War. Of him, The Illustrated London News said:

‘Suddenly arises a military adventurer with a peculiar audacity and cunning such as Oriental races can alone produce, who has been able, step by step and in the face of a wondering world, to establish, without let or hindrance and out of the most contemptible materials, a military despotism which threatens to depose the Khedive, and which defies, with impunity, the Western Powers and their ironclad fleets.’

Britain, alive to the fact that a crisis confronted her, displayed misgivings, doubts and justifications for seeking to protect interests in Egypt, and it was not generally thought possible that Britain would, or could, mount an expedition to go to Egypt. All possible steps were taken to settle without fighting; intense and prolonged diplomatic activity sought a peaceful solution, simultaneous with steps of an obvious military nature to pressure the Egyptians into compliance. When military operations eventually began, there was much foreign antagonism and criticism, and France, Britain’s sole ally in Egypt at that time, suddenly and dramatically reversed her policy of support.

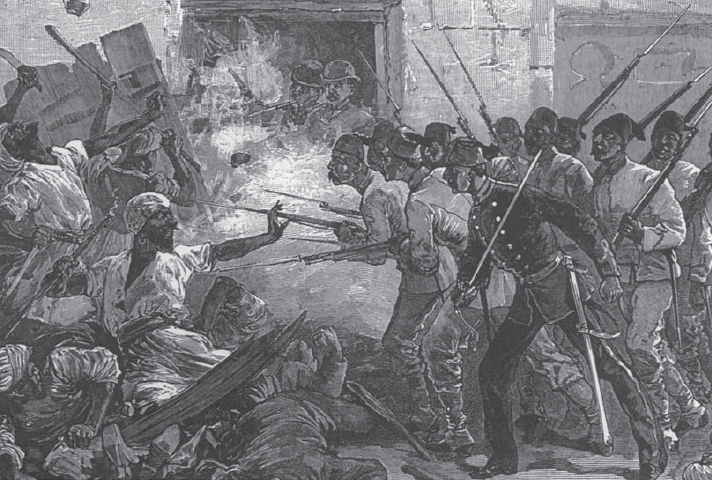

The rioting in Alexandria on Sunday 11 June 1882. After two hours, troops appeared at about 5 p.m. and charged the mob, which rapidly fled, leaving the streets under military control.

The war came about through a mixture of causes. The common factors were pride, financial interests and the maintenance of Britain’s interests in Egypt, not least the Suez Canal. The Egyptian War really began early in 1882 with a whimper, the Press stoking the fires by regular references to demands, grievances, protestations and stances of the antagonists, causing them to smoulder, fanned by assiduous man-made breezes, until finally bursting into flame. The British public played a major role, revealing archetypal Victorian fervour and patriotism, indicating that their esteem needed a British military victory. But not all were in favour of war, as was shown by fierce Parliamentary opposition, and pacific protests by such as Sir Wilfred Lawson’s Anti-Aggression League, the Peace Society, and the Working Man’s Peace Association.

The fortifications at Alexandria. A Krupp field-gun in a newly erected earthwork. The sentry is Egyptian, but the officers may well be Turkish as were many artillery officers.

Meanwhile the impassioned demands of Arabi that the foreigner be driven out of Egypt brought thousands to his banner; as a European Power, Great Britain could not submit to his authority and demands. In early June 1882 Britain found that she had drifted into fighting for the Khedive against his own Minister of War. Despite the presence ofthe Mediterranean Fleet, lying in harbour at Alexandria, rioting and the massacre of Christians continued in the city. Arabi, growing bolder each day, boasted that the forces at his command could hold the city against the fleets of all Europe. His trained engineers worked frantically to strengthen the shore forts and to throw up new earthworks in which they mounted heavy guns. So blatant was this work that, on the morning of 10 July, Admiral Sir Beauchamp Paget Seymour issued an ultimatum that either the forts be surrendered or they would be bombarded. Arabi’s reply indicated that he chose the bombardment, and the British ships cleared for action.

For weeks the British sailors aboard the ships of the Mediterranean Fleet had suffered disappointment and frustration as they lay under the shadow of the great forts, awaiting the signal-gun that would tell them to open fire. Typically, they had christened their enemy ‘Horrible Pasha’ and they could hardly wait to get at him – now it seemed the time had come as they stood in silence, stripped to their flannel jerseys, hoping against hope. Half-past six and the guns remained silent, a quarter to seven and no command given – then, ten minutes later, loudly and unexpectedly, the battleship Alexandra fired a shell at the Pharos Fort and the bombardment had begun.

Earthworks and batteries erected 600 yards from HMS Monarch in the harbour at Alexandria; they would be of little use during hostilities because the men in the batteries were exposed to the ships’ Gatling and Nordenfelt machine-guns.

This is the report our great-grandfathers read in The Illustrated London News of 15 July 1882:

‘On Tuesday morning, 11 July, after several weeks of anxious suspense, the attempts to bring about a peaceful settlement of the Egyptian difficulties were interrupted by a terrible conflict between the forts and batteries at Alexandria, under command of Arabi Pasha, and the British Naval squadron commanded by Admiral Sir Beauchamp Seymour, occasioned by the Egyptians’ conduct in persisting against repeated prohibitions, to continue their defensive and offensive warlike preparations. The Admiral had discovered on Sunday, that there were two new guns mounted on the western side of the entrance to the harbour, whereupon he prepared a proclamation to be posted up, charging the Egyptian authorities with breach of faith, and demanding the surrender of the fortifications within twelve hours. If this were not complied with he would fire on them after another twenty-four hours. There being no sign of a disposition on Arabi’s part to surrender, the bombardment was begun at seven o’clock on Tuesday morning. It is said that a launch was met at daybreak, with another deputation coming to promise that the fortification works would be stopped and the guns dismounted, but the Admiral replied that it was too late.’

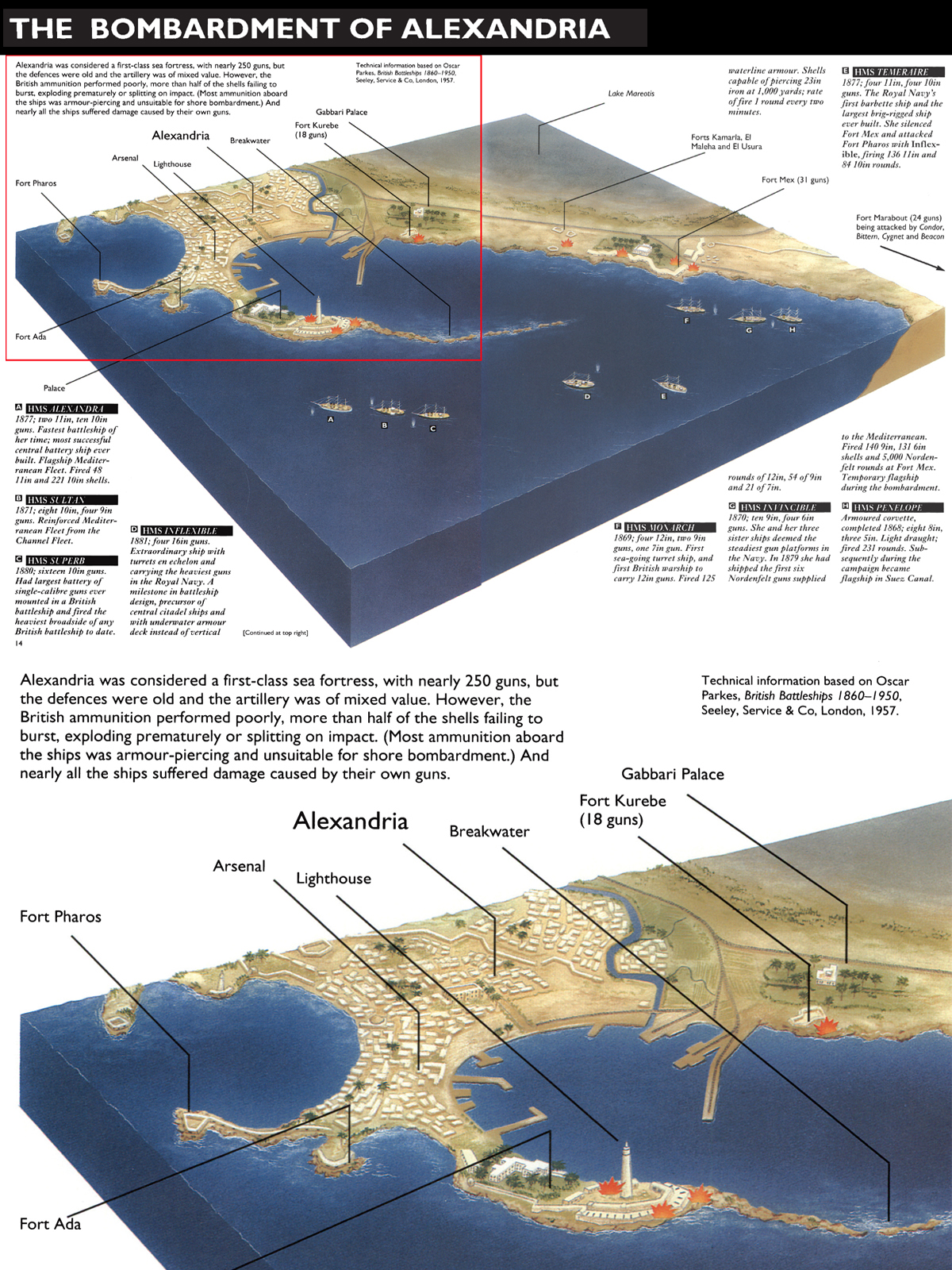

Alexandria had two distinct systems of defence: one protected the New Fort and Eastern Town, the other, dominated by Fort Pharos and Fort Ada, protected the entrances to the Outer Western Harbour. Admiral Seymour planned to deploy his squadron in such a way as to be able to bombard all the Egyptian positions simultaneously. The French squadron and other foreign vessels had left the harbour on the previous day; all was clear for action.

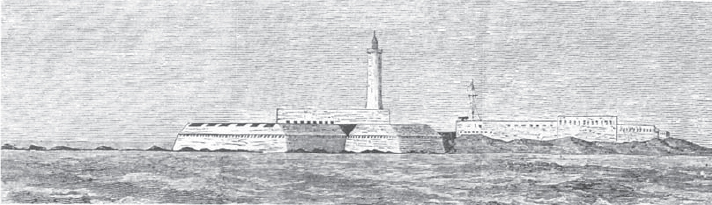

The Lighthouse Fort at the entrance to the harbour had a large, fortified barracks for 2,000 men. The guns of this fort were second-rate weapons, mostly cast-iron, smooth-bore 64pdrs, with a few rifled guns; it was considered that a single ship could dispose of these fortifications.

Panoramic view of Alexandria, from outside the harbour, looking east.

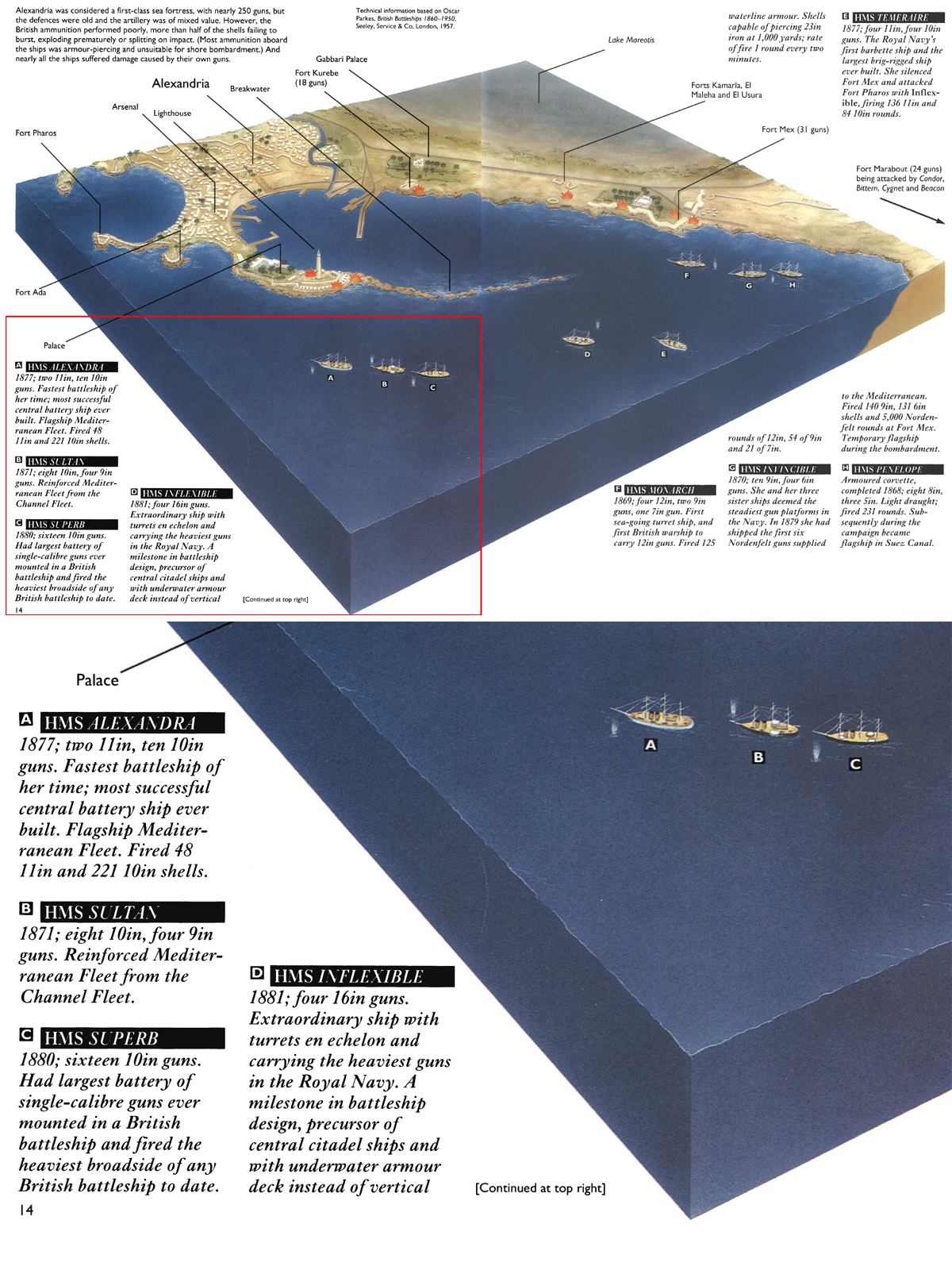

11 July 1882, as seen from the north, the last action in which a British battle fleet fought with muzzle-loading guns and the first in which it was protected by armour

The British fleet consisted of eight ironclads, supported by five gunboats. All the ships were fully manned and, in addition to their heavy armament, most of them were fitted with torpedoes and machine-guns of the modern Nordenfelt and Gatling patterns. The Squadron was under the command of Vice-Admiral Sir Frederick Beau-champ Paget Seymour, GCB, Flag Officer Mediterranean Station. He hoisted his flag in Invincible which, with Monarch and Penelope (Temeraire remaining on hand outside the harbour), took up positions commanding the entrance to the harbour, almost opposite Meks and 1,000–1,300 yards north-west of Fort Marsa el-Kanat on the mainland shore. They engaged these forts while Superb, Sultan and Alexandra engaged and totally destroyed the Lighthouse and Pharos forts. Inflexible co-operated with both divisions from her position commanding the Lighthouse and Pharos batteries, and Fort Meks.

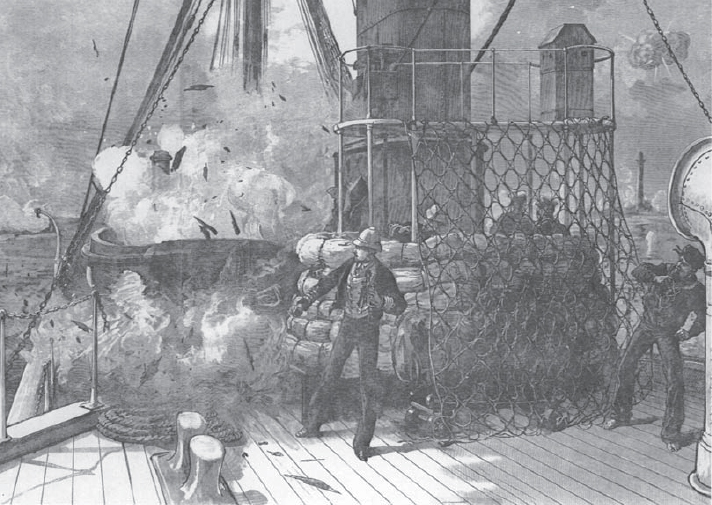

This sketch by the war artist Melton Prior depicts the crew of a Nordenfelt machine-gun, protected by a rampart of hammocks on the upper deck, preparing to open fire on the Egyptian gunners in the embrasures of the shore battery.

Sketches of various aspects of the action, by special war artists of The Illustrated London News. From top to bottom: Fort Ada, blown up by Superb, and the magazine behind Barrack Fort, blown up by Alexandra; the fight at its hottest, south of the Lighthouse Battery; the meeting of Alexandra and other ships after the action; the damage inflicted upon Lighthouse Tower; and a shot hole through a funnel on Alexandra.

The respective positions of the warships off the Lighthouse Fort, and their targets ashore.

This drawing by Melton Prior, made aboard HMS Alexandra during the attack, shows the working of the 10in broadside guns (port side).

At close range the five gunboats engaged the Marabout batteries at the entrance of the harbour and soon silenced them, after which they ran in and shelled Fort Meks; Bittern covering a landing-party from Invincible which blew up the heavy guns in that fort. The Egyptians fought their batteries with more determination than had been anticipated, but by 4 p.m. all had falllen silent; four had been blown up, and the Khedive’s palace was on fire.

Another sketch made aboard Alexandra by Melton Prior: a shell from a shore battery hits the vessel. Her hull was struck by 25 missiles. During the action one man was killed and two wounded.

The bombardment ceased at half-past five, when it was reported that five men had been killed and 28 wounded; the wounds mostly caused by splinters when solid shot penetrated inboard, the Egyptians apparently having no explosive shells. The casualties among the Egyptians must have been very great, but we are unable to obtain any idea of their number. As soon as firing had ceased Admiral Seymour sent ashore twelve officers and men who made their way to the ruined forts and destroyed the guns with dynamite.

On Wednesday morning, as had been planned, Forts Napoleon and Gabarrie, and the inner harbour batteries, were engaged by Invincible, with Monarch and Penelope which had entered the inner harbour the previous evening. Invincible silenced the batteries, then landed a party which spiked and burst nine guns. Towards noon Inflexible and Temeraire opened fire on the Moncrieff battery outside the harbour, which had been repaired during the night. The battery did not reply. The Khedive’s palace was still burning, and there were other fires in the town. The wind had risen and there was a sea swell which made manoeuvring in the confines of the harbour difficult.

HMS Sultan off Rasel-Tin, or Lighthouse Fort, at Alexandria, July 1882.

Inflexible (in the foreground) with other vessels in action in the background. Her 16in guns played a prominent part in the action, one of their huge shells dismounting a 10in gun in one of the Egyptian batteries, turning it end-over-end, and killing the entire crew.

This 774-ton gunboat was armed with one 4½-ton, one 7½in calibre and two 64pdr guns; her complement was 100 men.

Commanded by Lord Charles Beresford (right), HMS Condor energetically engaged the Marabout Forts at the western extremity of the Bay of Alexandria.

Interior of the Egyptian Lighthouse Port after the action had ceased.

With fires still burning in the city after the bombardment, the British naval landing party pull towards the shore. In the background is the Khedive’s palace.

The naval landing-party marching up the Marina in Alexandria, drawing a Gardner gun.

Two sketches by Melton Prior. Below left: the execution by a naval firing party of an Arab incendiary caught in the act in the streets of Alexandria. Below right: the arrest of one of Arabi’s spies by Royal Naval police at the Moharrem Bey Gate in Alexandria.

But at one o’clock the signal ‘Cease Firing’ was hoisted in the Admiral’s flagship outside the breakwater. A white flag had been flown in the town, signalling the desire for a truce. The Admiral sent a gunboat, with a white flag at the fore, up the Inner Harbour to the Arsenal wherein were the official residences of the Ministers of War and of Marine. ‘At the time of writing this, on Wednesday evening, nothing more is known; but we may hope that a suspension of hostilities is already arranged.’

It had been thought that the naval action at Alexandria would be enough to destroy Arabi and restore the Khedive’s authority, and for some time Cairo and the rest of Egypt remained quiet, watching events. When it was seen that the British apparently were content to remain inactive within the confines of Alexandria, belief in the star of Arabi revived and the entire nation again threw in its lot with him. Had the Government in London immediately dispatched a force to march against Arabi, there can be little doubt that they would easily have defeated his dispirited army, but British reluctance to commence open warfare gave the Egyptian leader time to regain lost prestige. He withdrew his troops to what became a strongly fortified position, brought up heavy artillery and increased the size of his army. Thus emboldened, he issued a proclamation declaring that, ‘irreconcilable war existed between the Egyptians and the English’.

The British Government was still far from united on Egyptian policy and, while other European powers were not unsympathetic towards the bombardment of Alexandria, they were quite unwilling to give Britain an explicit mandate – France would only co-operate with Britain in defence of the Suez Canal and became increasingly hostile to intervention of any kind. Nevertheless, the powers did not interfere and so British policy, practically unfettered and, with public opinion and the press in jingoistic mood, settled upon the dispatch of an expeditionary force to secure British interests in Egypt. The War Office and the Admiralty acted with unusual energy and promptitude, and on 25 July the Queen signed the Proclamation calling out the Army Reserves; two days later the first of them, including Royal Marines, sailed from Portsmouth. Before the end of the month the Guards had left London, and by 15 August two divisions, each of two brigades of infantry, with cavalry and artillery, were on their way. A Staff Corps composed of the three squadrons of the Household Cavalry, two regiments of Dragoons, with artillery and a siege-train, commissariat, transport, and medical department, was dispatched from Britain.

Seaman of the Naval Brigade. The sennet hat bears the ship’s name on a tally band. The rifle is the Martini-Henry with cutlass bayonet. (G. A. Embleton)

Expeditionary Force to Egypt

| From Britain: | Officers | Men |

| Cavalry | 118 | 2,174 |

| Artillery | 56 | 1,514 |

| Engineers | 30 | 876 |

| Infantry | 270 | 6,958 |

| Medical, Transport and Commissariat Branches | 38 | 1,384 |

| Total | 512 | 12,906 |

(Nominal force according to the Official Return)

From Malta:

1st Bn South Staffordshire Regiment

3rd Bn King’s Royal Rifle Corps

1st Bn Berkshire Regiment

1st Bn Gordon Highlanders

2nd Bn Manchester Regiment

Four Companies 1st Bn Sussex Regiment

From Gibraltar to Malta and then on to Egypt:

2nd Bn Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry

From Gibraltar:

1st Bn Cameron Highlanders

2nd Bn Derbyshire Regiment

From Cyprus:

HQ and four Companies

1st Bn Sussex Regiment

From Aden:

1st Bn Seaforth Highlanders

From Bombay:

1st Bn Manchester Regiment

Total: 40,560 officers and men

The Scots Guards under their Brigade Commander, HRH The Duke of Connaught, marched from Wellington Barracks to Westminster Pier in London on 28 July, to embark in three river-steamers for Albert Dock.

The total of all troops from Britain, the Mediterranean and India was 40,560 officers and men of all ranks.