Born in 1950 in St. Louis, Missouri. Worked as a freelance photographer in the 1970s and ’80s, attended shows at various venues throughout Los Angeles County, and lived in Beloit, Wisconsin; Freetown, Sierra Leone, West Africa; Los Angeles and Berkeley, California; and Tokyo, Japan. Currently lives in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, and works as a freelance photographer.

I WAS BORN IN ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI. As a child we lived in an apartment building, but then we moved to a suburb called Kirkwood. I think I had a pretty normal suburban upbringing. I have an older sister and younger brother. My father was an artist until the children were born and then he had to take a straight job, so he became a surveyor. He built our house. He did really abstract paintings. They were beautiful watercolors of towns. During World War II he was a cartoonist for one of the papers, but then he progressed. He was really more of an abstract expressionist. He had showings at galleries and a show at the St. Louis Art Museum. He would always be painting in the basement. As a kid, I would go downstairs and he’d say, “What do you see here?” and I’d go, “Well, I see a town.” He would say, “Yes, that’s right. It’s a town. You got it.”

My mother became a teacher. She raised us most of my life. She was at home when I was a young person, but then she started teaching seventh grade. She taught her entire life. We lived in a suburban American existence of riding bikes, being wild Indians, running around, throwing rocks at each other, and having tree houses and a creek. It was a different world then. I think we were really free and my parents were pretty loving parents. My mother had been abused as a child, which effected all of us in some way or another, but I had no actual experience of that myself.

When I was in college, I spent a year in Sierra Leone. When I came back I felt quite alienated by the United States. I was only twenty-one or twenty-two. When Nixon got reelected, Jeff Spurrier, my partner, and I were very disenchanted, so we moved to Tokyo. We were in Tokyo during all the glam rock of that period. Even though that was happening, we were unaware of it. We were just listening to jazz and we never really liked the mainstream Western music that was happening during that decade like Steely Dan, Fleetwood Mac, etc.

When we were in Japan, Jeff started working for Rolling Stone Japan and I started shooting. I was a sociology major, but I didn’t really like it that much. When I discovered photography, I got very much into it. I’m a very social person. A camera gives you permission to kind of invade somebody’s life. At the time, I had a couple of mentors in Tokyo. At some point we realized that in order to have our careers, we had to move back here. We couldn’t figure out where to settle. I had an interview at New West Magazine in Los Angeles, and the art director said, “Yes, we can use you.” He gave me three assignments total. That was it. On the strength of that, we moved to L.A.

We came back to the States and decided we wanted to be journalists. We were living in a small apartment on New Hampshire, at the corner of Vermont and Santa Monica with our two cats that we brought with us from Tokyo. It cost around $160 a month. We were not that into L.A. It took a long time. We didn’t meet people we really liked, but then I met this woman on the bus. It turned out her duplex was empty, so we moved over to Silver Lake. Then we were in this duplex that was magical. Lari Pittman and Roy Dowell were on one side and Cathy Opie was on the other side. There were four apartments. Robert Lopez, who was in the Zeros, lived there for a while. Jon Bok the designer, and later Ron Athey the performance artist were also there. There was something about that area that attracted artists.

![]()

In the later ’70s, we somehow went to a show. I cannot remember what the first show was, but our minds were blown by the whole scene. For me as a photographer, I was always looking for something that was visually interesting. Up until then, I felt like the things I was shooting were boring and I had to make them look interesting. All of a sudden I realized, “Wow!” This was something new and different and exciting. Visually it was really amazing. It was pre-Internet. It wasn’t like one person put a safety pin in their cheek and then the whole world would have it. Each different little facet took time to develop.

We would go everywhere—the Whisky, the Roxy, the Starwood, Club 88, Madam Wong’s, the Vex, the Anti-Club, Cathay De Grande, Ukrainian Culture Center, the Masque. There was the ON club, which was kind of a punk reggae club. I liked the energy, the music, the passion, and the general vibe of it all.

In ’79, I had to get a job. I worked at the L.A. Times as an administrative assistant or something for a year. I hated that job so much that it actually gave me vertigo and I was hospitalized. The good part about that job was that one of my bosses was Robert Hilburn. As a perk, I used to get passes to the shows. I would go out until five in the morning and then I’d go in to work at nine in the morning. It was really crazy.

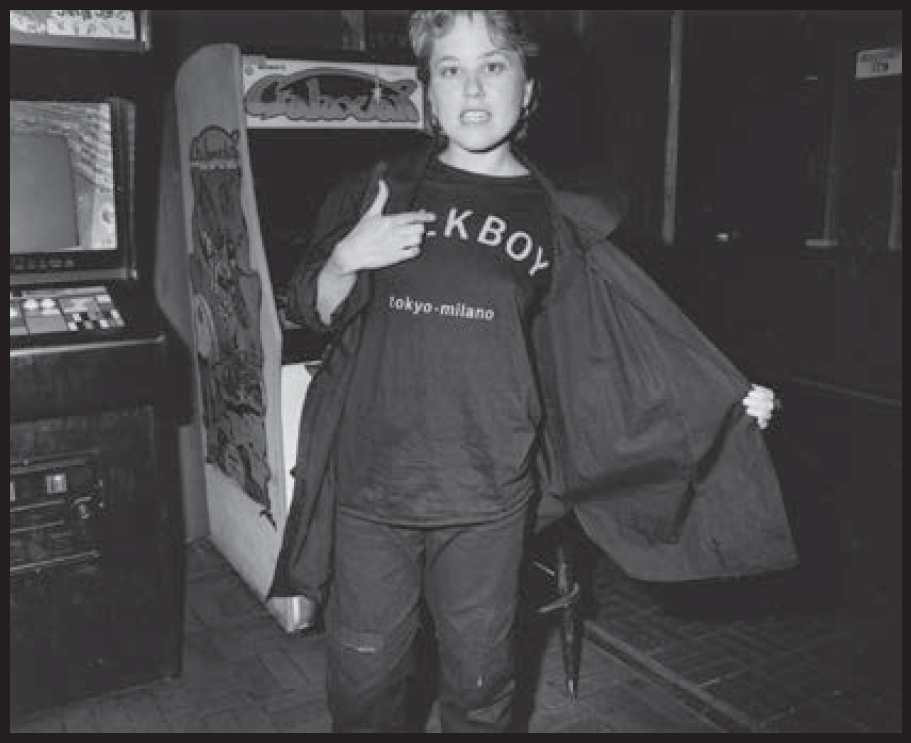

I always had my camera at the shows. The camera gives you a reason to approach and start talking to people. The punk thing was different, because people weren’t as approachable. Part of it was the “fuck you” mentality. “Don’t take my picture.” I think in general, though, people like being photographed and it kind of gives you permission to do that.

I worked a lot for the New York Rocker. I had covers with them. The L.A. Reader was published at the same time as the L.A. Weekly, but the Weekly kind of trounced the Reader. The Reader, in a way, was almost more alternative. One of my editors was Matt Groening, the Simpsons creator. The editor/publisher, James Vowel, was a former L.A. Times staffer, and he believed in me. Jeff and I started doing a column for them that was similar to Pleasant [Gehman’s] column in the Weekly. We would go out four or five nights a week, and it was kind of this music/gossip column. Jeff also started writing a weekly column for the Times. I would often shoot photos for that, too. That’s how I started building my portfolio.

I eventually worked for Rolling Stone, Cream, and others. I didn’t really work for the little fanzines at all. I started my career as a photographer very late, because I didn’t find it until I was in my mid-twenties, but I felt like I was really learning how to shoot and so I was very loose and spontaneous. I think it also gave me an absence of fear. I’m not afraid at all to approach people and I think maybe I kind of got trained to not have fear by the punk rock experience. I find my students get scared to actually get in somebody’s face, because they don’t want to invade their space or whatever, but I always tell them, “If you ask somebody to take their picture, then they’re going to say yes or no. If they say no you just got to move onto the next person.”

At one point with my career, after I left the Times around 1980 and I freelanced for the alternative press for a couple of years and worked in labs and other odd photo jobs, I realized that I needed to start working for magazines. I don’t even know how I actually survived that time. I always considered myself a journalist. That was my focus and my goal. I put together my portfolio and took it to New York. It was really lame, but I got work out of it. I don’t know how. Eventually I started shooting for Guitar World, Guitar Player, and some of those more established rock and roll magazines. Then I started working for Conde Nast and Hearst and Time and all those bigger publishers.

Through my late- or my mid-thirties through my fifties, I was working steadily as a magazine photographer or editorial photographer. I also worked for Getty Images and then I started working for Corbis. It all just kind of mushroomed and I started teaching at Otis [College of Art and Design] in ’95 when they were still in MacArthur Park. They needed a professional to teach editing and lighting. I’ve been teaching there yearly up until this year.

![]()

I think in a way punk rock influenced my politics. It’s like the absence of fear thing again. I’m a very political person and I’ve always been really involved in politics. I was a member of the Women’s Action Coalition (WAC), which was created after Anita Hill. It was a group of artists that formed in New York and then in Los Angeles. We had three or four hundred members in L.A. We used to do what we called “actions.” We would go out and protest. It was mostly built around sexual harassment, because of Anita. I don’t know if I would have had the ovaries to do some of the things we did in WAC if I hadn’t been involved in the punk scene. We did some really outrageous stuff. I was the “Minister of Information,” which was fun.

In terms of feminism, I was a feminist before punk rock. I became a feminist in college, reading Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem. That’s a battle we’re still fighting. To me, that’s kind of what’s going on right now with the presidency. Women are still not equal. We make seventy cents on the dollar, and there’s still all this abuse and harassment. It’s like a war against women and I feel like that should be the most important issue, because we’re the majority.

In the beginning of the punk rock scene, women were welcome. When it got more hardcore, it became less welcoming. I remember being at the Anti-Club with a girlfriend, and she was pogoing in ballet shoes. Later you had to wear jack boots or you would never get anywhere near the stage. Her feet would have been mauled. In terms of being female or male, the men were a lot more aggressive, but I never felt anything against me personally. One night a bottle almost hit me in the head onstage, but I don’t know who threw it. It was almost more anti-photographer than anti-women.

I would not say I’m traditional in any way, except for being monogamous. I don’t really think about it much, but sometimes I do, especially living in Mexico. You feel like a lot of people that end up here are kind of off the beaten track. I didn’t grow up in Kirkwood. I didn’t stay in Kirkwood and have kids. I feel like that might have been more because of feminism than anything else. Maybe feminism and my experience living in Africa for a year and then Japan really kind of informed who I became. I just never wanted to be a suburban housewife. My career was always really, really important to me.

When people say, “Why don’t you have children?” we say, “Oh, we forgot.” The reality is, we did kind of forget. We were so busy with our careers and just traveling and going out, and having children was never a priority for me. I just didn’t feel that maternal urge to have children, and I feel like the life I have now I would not have had if I’d had children. It’s not like I didn’t have children so I could have a career, it’s just that it was never a priority to have children. It’s fine. It’s kind of a relief in a way.

My connection with the punk rock scene sort of comes and goes. Recently, there was the publication of the John Doe book [Under the Big Black Sun]. My photo was on the cover of that book, which was super cool. John and Exene did readings and all of us photographers showed up for book signings at the Central Library in downtown Los Angeles. They also did a reading at the Grammy Museum, and then we all went out afterwards. It was very weird, because we’re all old now and everybody is sort of mellow and settled. It was just great to see everybody. It really made me feel more of a connection than I’ve felt in a really long time. I mean, it’s been forty years, right? Thirty years or forty years?