Born in 1949 in Buffalo, New York. Lived in Seattle, Washington, and Los Angeles, California, in the 1970s and ’80s and worked as a performance artist. Currently lives in Los Angeles and works as a lecturer, performance artist, and spoken word performer.

MY FAMILY WAS REALLY POOR. We moved to Seattle from Kansas, thank God. We were lucky to do that. My dad worked for Boeing in Seattle. He was a flight engineer. My mom was really sick all the time. I had two older brothers and a younger brother and sister. I had to take care of my younger brother and sister, because my mom was constantly hospitalized. I always took care of those kids. I was like a mom at a really young age. I learned to cook when I was around four years old. I would stand on a chair and make scrambled eggs. My mom died when I was around eleven, but she’d been hospitalized almost the whole time since I was five.

We didn’t always have a TV, and half of the time it didn’t work. We would have sound or picture, but we rarely had both. I used to watch the Mickey Mouse Club. I’d dance around. I really felt like I was somebody. Nobody in my family did. They thought I was somebody who was supposed to clean up after them and take care of things, which was okay. I did it.

My mom, my dad, everybody, would say, “Don’t sing. Don’t sing. You sing off-key.” I didn’t listen to it. I didn’t care. I would sing as loud as I wanted to. I would make crazy costumes for my dog or my little brother or sister. I never went to an art museum until the eighth grade when I went one time. I never went to movies, except something like The Three Stooges, if I was lucky. I didn’t have any cultural background.

I went to Catholic school and hated it. I used to hang out in the library and read mythology. I always loved horror and really scary stories. I didn’t believe in what my parents believed or what anybody believed. I tried to just keep going, keep surviving. I was a really wild teenager, because my mom died. I started smoking and drinking at a young age. I didn’t do great in school, but I wasn’t stupid, so I did okay. I never did homework, but I got decent grades.

After I graduated from high school, I went to beauty school and I started hanging out in theater. Seattle has a big theater scene. There were all these little theaters where they would do Chekhov plays. I would just hang around and try to get a role. Most of the time I was doing set stuff or stage management or makeup. Anything I could do, I did.

I was at this party in 1974, and I met this guy, Tom Murrin. I was working at a pharmacy in Seattle. I met him and it was like one of those moments where I went, “Oh, God. I just met somebody who was amazing.” I think he thought the same thing. He had just gotten to town on that day. He was a lot older than me—about eleven years older. He grew up in Los Angeles, became a lawyer, and at twenty-two years old he was the youngest lawyer who ever passed the Bar in Los Angeles. He met Ava Gardner in a Beverly Hills law office where he worked. She said, “Come to Spain with me.” Because he was kind of a boy toy, he went to Spain with her. They were great friends for his whole life, until she died.

He went to Spain thinking he was going to be Ernest Hemingway or somebody. He was trying to write. Then he tried to paint. Then we went back to New York, and started hanging around the theaters. He wrote some plays. He traveled with these plays, and did these plays, and lived in Paris for a while. He moved back to New York and went, “Oh my god, I have to stop using drugs, and drinking too much, and smoking.” He was probably in his early thirties.

He moved to Humptulips, Washington, to work with some guy he had met in Paris. He was doing these weird plays in this strange little town called Humptulips, which was basically a truck stop. I think it had a bar and maybe a store or something. He lived in a little tiny trailer. He was trying to do these plays in this bar for lumberjacks and their girlfriends, and a lot of drunk people. That didn’t work out for whatever reason. He went to Seattle.

That day, I met him at this party in the evening. We just clicked. He said, “Come over to my apartment. I’m going to do Balloon Theater.” It was sort of a thing that was made up. I said, “Okay, do I have to audition?” He said, “No, no, you’re perfect. Just come.” So I showed up, and we went out on the streets. We went to Pioneer Square—the big, huge farmers’ market there. We were dressed up and we had all this glitter on our faces. We had some balloons and we were moving in a sculptural way. Who knows what the hell we were doing. He had worked with the Theatre of the Ridiculous and the Theatre of the Absurd in New York. It was pretty intense. People were interested, and it completely changed my life. I got my picture taken right away and was on the front page of the Post Intelligence or something. I was like, “Okay. This is it. I can do whatever I want to do and it’s my performance. If anybody doesn’t like it, they don’t have to like it.”

Tom said, “Okay, we’re going to take this show on the road.” A few of us left town, and we started traveling. We went down to Los Angeles, and then most of the people left. We started doing shows wherever we could do them for a couple of years. In ’77, his dad passed away. His dad was here in L.A. We used to stay with his family. All of a sudden, he wanted to go to Asia. He wanted to go to India and Japan. He wanted to go to Hong Kong. I didn’t have any money to do that, so I stayed here.

I started playing at this little tiny coffee shop which was right down the street from Los Angeles Community College. I lived in this apartment with one little tiny bedroom, which was as big as a closet. I was really poor. I didn’t have a lot of money. I worked three jobs sometimes. I did window dressing. I worked at a wallpaper warehouse. I did all this stuff. I dug in the garbage for props and things. People would give me their old clothes. I’d make dummies out of them.

I had my props and costumes, and I just said, “I’m going to go down to that coffee shop. It’s the closest thing.” The guy who owned the place said, “Okay, I want you to be a regular.” Every week I performed there. I kind of taught myself how to perform. We had already performed all over. We’d performed in Europe, New York, and Baltimore. We traveled the whole United States performing, but it was street theater, so it was just flying by the seat of our pants.

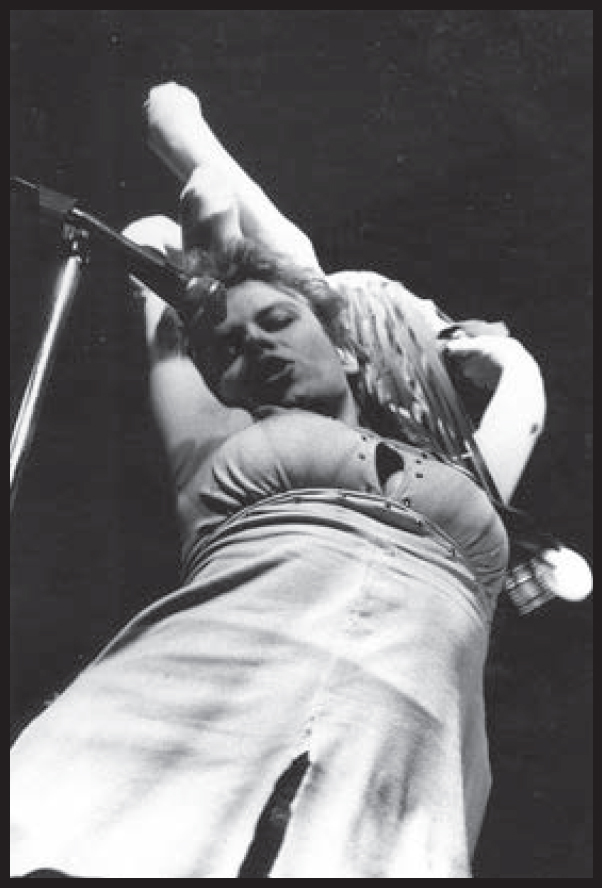

I started doing it there at the coffee shop. Then I wanted to do music. I wandered into the Masque in late 1978. I saw the Mau Maus play. I was like, “Okay, I think this is where I want to be.” I was already making my own blood and my own costumes. I’d gotten to the point where I had a solid visual presentation. I really wanted music. I wanted some kind of backup. I wanted the band.

I ended up going down to the Hong Kong Café and talked the guy who managed it into booking me. He put me on the bill. I think the Plugz were on my first bill. I performed and got fifty bucks or something. I was like, “Oh my god, this is great.” I had a drummer who I had just met three days before. He didn’t even show up on time, which really looked bad for me.

Afterward my friend, Z’EV, a percussionist from San Francisco who was originally from Los Angeles, came up to me. He was a really well-known, avant-garde percussionist. He said, “Get rid of that guy. That drummer. He’s no good.” I said, “Believe me, I’m getting rid of him. He didn’t even show up on time.” Z’EV came to my apartment the next day. He said, “I’m playing with you.” He played huge pieces of junk—a car fender, any kind of piece of metal or shit he could find. He was amazing.

I became a regular with Z’EV at the Hong Kong. We would drive up to the Mabuhay and play in San Francisco. Dirk Dirksen, who ran the Mabuhay, was the greatest guy. He loved my show. He always put me on. He always paid me decently. I became a headliner there. I started playing more shows in L.A. I got on the cover of Slash magazine. It snowballed from there.

![]()

The West Coast scene was totally different from New York. It wasn’t a copycat scene. In New York, there was a lot of stuff going on. A lot of really great music came out of there, but I felt like the West Coast energy was grounded in the West Coast. There’s more space. There’s more room.

When I performed in New York, it was always difficult. Here, I threw all this crap in my car, or a friend’s car, or whatever, drove down to the Hong Kong, did my shows, packed up, threw it back in my car, and drove home. In New York, it’s a different landscape. It’s always harder. That’s why I didn’t go to New York.

It’s easier here. I was able to give a bigger presentation. I’m a West Coast gal. What can I say? Once my family moved from Kansas to Seattle and I saw the ocean, I could not believe the power of that water. That air. The breeze of all of that. I am not somebody who can be crowded or feel contained.

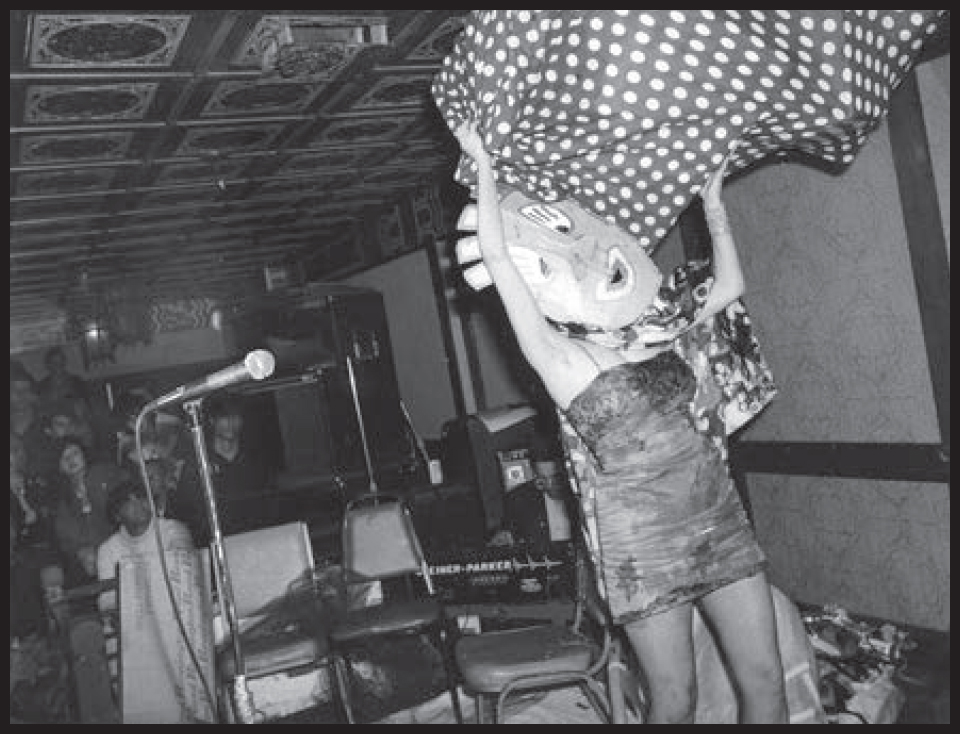

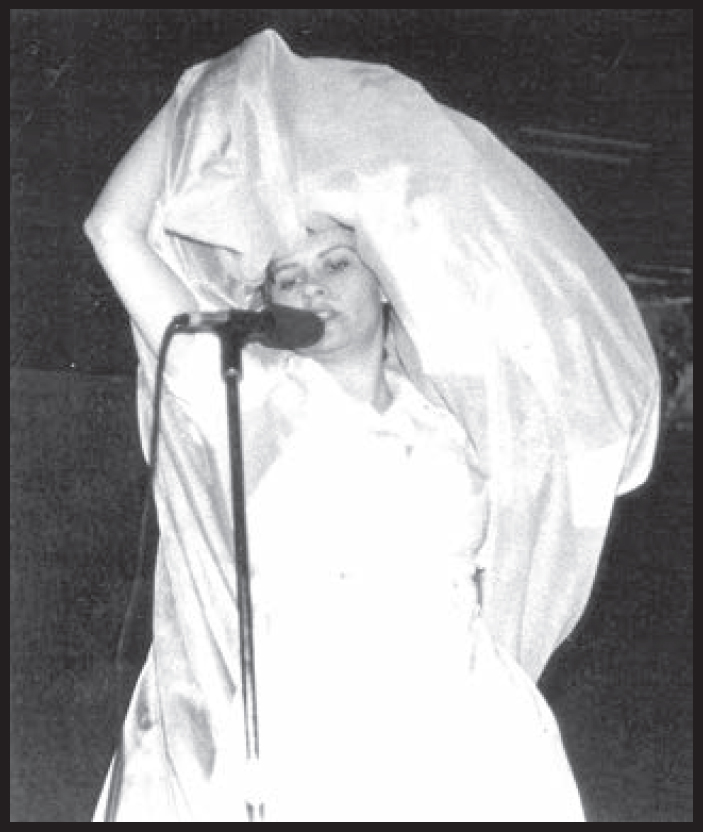

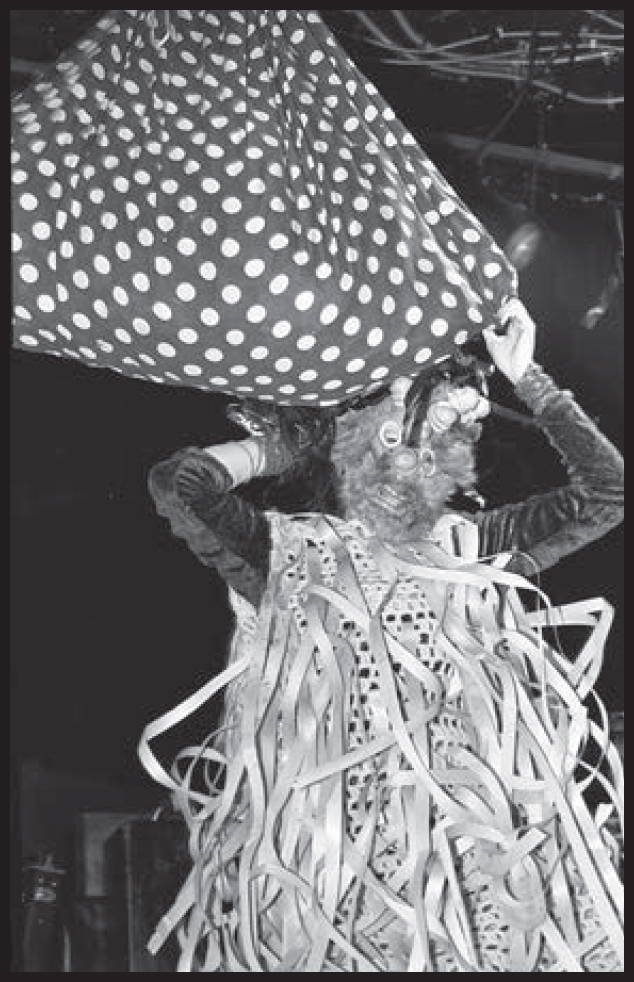

My performance art came from my feeling that I could do whatever I wanted. I used to write my dreams down every single night. When I was lacking inspiration, I would go to my dream book. I would try to make a costume or a prop or something that represented that vision that I had when I was asleep. I really felt that whatever I did was a direct inspiration from the collective consciousness of my audience, and my community, and my world.

I could not believe how I was embraced by the punk rock community. Most of them were quite a bit younger than me. It wasn’t as censored as things are now. Kids used to come to these shows. They were moved by it. Quickly, I moved to headlining. I had a full band. I played with Fear a lot. I played with the Dead Kennedys up in San Francisco. I played with the Mutants. One time, I played with Black Flag. I played with the Germs.

Around 1980, Z’EV decided that he wanted to move to Amsterdam. Mark and Brock Wheaton, brothers from the Seattle band Chinas Comidas, came down to Los Angeles and played some gigs. The band split up. Mark Wheaton called me, and then Mark and his brother started performing with me. I said, “Look, these are the rules. We don’t practice. We play. You do what I do. Which is, you key into the consciousness of the audience, and you improvise. Like jazz. Like anybody who is disconnected from the rules.”

I tried to make a little script, like how a band has a playlist. It was usually from my dreams. Sometimes I would follow it, but if I didn’t feel like following it, I didn’t. Once the blood came out, once the really gooey, messy shit came out, I tripped on it and I fell down and I slid, and it was messy and impossible to keep going.

My idea was to create a different show every time. One of the things that always bothered me about regular performance art, or performance in general and even dance, is they play a set list. They play the same song. They play it over and over. They play it each night they play at a different club. For me the idea was, how do I mix it up? How do I break that string of consciousness? How do I make some kind of explosion happen by cutting through the expected reality and going into a more cosmic, confused state of being?

A lot of the performances were very trance-based. I would go into a state where everything I did was sent to me by the collective consciousness. I had these ideas and I put them out there, but if during the performance I didn’t feel that it really jived with the moment, then I didn’t do it. I’d go to something else. I prepare the props, and the costumes speak to me. They tell me what to do, and I follow.

![]()

In the early ’80s when I was performing, I was not a part of the art scene. In fact, I was pretty much rejected by any kind of art scene. I did not know what performance art was. The first performance art I saw was a Robert Wilson production at the public theater. I saw this guy, Christopher Knowles. He read the phone book. Actually, he didn’t read the phone book. He knew the phone book. I thought, “Okay, I get it. This is performance art? I think I’m a performance artist.” I started calling myself a performance artist. There’s no other way to explain it. I’m performing in a moment, in a time, and this is my art form. It’s certainly not a play. It’s certainly not a piece that’s going to be repeated. It is a performance, in a space, time, and place. I try to be as honest about what I put out there. I try to connect as much as I can with some kind of unconscious. If that’s not pure enough for people who want theater, or they want a music set, or they want something that’s been rehearsed, or whatever, I don’t care. This is what I have and this is what I have to give.

The first time I started using blood was in ’74. I learned to cook when I was younger, so I cooked up this blood recipe. I can’t remember all the shows where I used it, but I remember in ’74, I was in New York. It was summer, and it was really hot. I made these weird nipples under my bra out of balloons and blood that I cooked up. I was in Washington Square Park. I learned some magic tricks, too. So I would do this thing where I would cut my nipples off. I got a little bit of flack from certain feminists about that. I understand. I agree. It’s kind of weird. From then on, I used blood and I made my blood recipe.

After a performance, I was exhausted. Then I had to clean up. The clean-up was a mess. A huge mess. Sometimes if I had a band play after me, I had to clean up the stage really fast. My costumes were ruined. I’d have to throw shit away. I’d save some pieces and use them for something else. I turned them into a new thing, but I always felt that they had the power from that last performance. I also have this strange connection with objects and things and textures and colors and movements. The way I move my arms. The way I move my body. If something comes to me, I trust it. I trust that is the expression that I am supposed to put across. If I destroy a costume I really love, I say goodbye to it. I sacrifice it. I say, “Okay I’m good with this.”

![]()

You can’t walk through life as a woman without experiencing sexism. What woman doesn’t experience that? But I got to tell you, there were so many inspirational women back then! There were so many voices, and they were so powerful. And they kept coming. It wasn’t just a short period of time. I was just unbelievably inspired by the women in the scene.

Being a woman artist is like being able to own your sexuality. It’s being able to own your sex. Being able to identify with your core being. My core being is feminine. That’s it, man. I have a pussy. That’s what I have, and that’s what I like, and I’m good with it. I can’t say that I don’t like the penis, ’cause I do. I like all of it. I think it’s authentic to own your sexuality and also your animal self.

I always say I am an animal first. All that brain pudding is so confusing. When you look at a dog or you look at a cat, their animal core is the driving force. I trust that more than the deepest, most philosophical thought. Most people don’t. I feel that it grounds me to the earth. I really believe it’s important. Many people have told me that I am anti-intellectual, but I’ve always been fascinated with thought, and with different people’s opinions, and I listen to everything. I don’t have to believe what other people believe. As a really young kid, that was my breakthrough.

When my parents used to take me to church, I would see the Holy Communion wafer and I’d go, “That’s the moon.” I couldn’t believe what they did. I knew that they were lying to me. I knew that there was no truth there. I knew, and I trusted that they believed it, but I also trusted that they had some questions that they were not courageous enough to face. I had to face those questions, and I had to ask those questions. I always did. I was punished. I was punished to the point where sometimes I would just shut up about it, but I didn’t lose my own self.

I live for art. I love art. Art has given me everything that’s good in my life. I live in the Hollywood Hills in a really nice house, and I came from the projects in Seattle with nothing. Art will give you everything you need. You always have to trust that. It really will. It’s magic. It’s the magic power. It really is.