Born in 1961 in New Haven, Connecticut. Lived in New Haven and Los Angeles, California, in the 1970s and ’80s and played bass for Waxx (1977), SAUPG (1977–present), the Visitors (1978), the Monsters (1979), Twisted Roots (1980–1983), Sexsick (circa 1981), DC3 (1983), Black Flag (1983–1985), and Dos (1986–present). Currently lives in Los Angeles, where she works as a freelance sound editor and plays in the bands SAUPG, Dos, and Awkward.

I WAS SIXTEEN when I first got involved with punk rock. Paul, my older brother who is three years older than me, introduced it to me. He went to school with Paul Beahm, who became Darby Crash in the Germs. We were friends with those guys, him especially, right into them starting the Germs. My first gig was a Germs gig at the Whisky. My involvement at the beginning was as a fan, although I was already playing the bass guitar. Later I started to play with friends and played in numerous bands in Los Angeles.

I was going to high school every day. I was hungover a lot from the night before. I was practicing with bands almost every day. Schlepping my bass. The scene was full of people who weren’t maybe pushing that hard. They weren’t working all the time or weren’t working at all, but that wasn’t me.

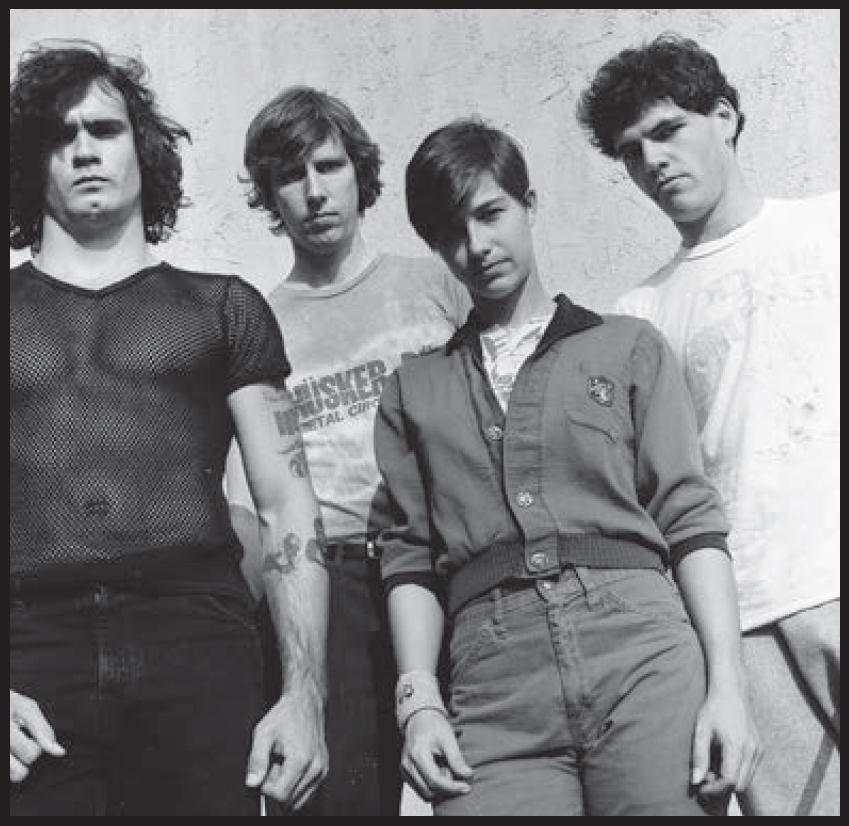

My first band was called Waxx, with my brother on drums. Although he was a keyboard player, he didn’t think that punk rock had keyboards, so he played drums and one of his good friends, Glenn, played guitar. We had another friend who sang. We got a gig through Rodney on the ROQ—a Sunday show at the Whisky. We played with Crime and the Dils in 1977.

I was called Candy Cane. That was my punk rock name at the time, because I thought we had to have one. I don’t know how I came up with that. I’d gone to the thrift store and gotten this candy striper’s outfit, so maybe it was that. I thought I had to have a name, as if my name isn’t cool enough, which I now think it is.

My first band played a few shows. We didn’t play very many because Paul joined the Screamers, who were much bigger and kind of known around town. The Screamers were a keyboard band, so it was a much better fit for him. Glenn, the guitar player, and I went on and had two more bands. One was called the Visitors with a guy named Spazz Attack who had been in a Devo video. That was his big claim to fame. He wasn’t a great singer, but visually he was a really cool performer and dancer, so he was our singer. We had Dave Drive on drums, who later on was in several bands, including the Gears, who played around town for a long time. After that band, Spazz left and we were in a band called the Monsters. We got Nickey Beat from the Weirdos to join our band. The Weirdos had been one of my favorite bands, so that seemed like a real coup at the time. We had this other guy, Leroy, singing. The only problem was that Nickey was fixated on the fact that we couldn’t play live until we could headline the Whisky, because, of course, he had headlined the Whisky with the Weirdos. So we never played live. He just couldn’t start at the bottom, which is sort of understandable intellectually, but we were stuck. So we practiced a lot. All the bands practiced a lot. I can’t tell you how much time I’ve spent in garages and practice pads playing in bands endlessly, with no gigs or very few.

In the early days at the Masque, they had practice rooms. I had this deal with the guy who ran it. I would cover in the afternoons, letting bands in and out and renting equipment. In return, he would give me free practice time. So, I would earn free practice for my bands. After school, after twelfth grade, I would come and get my band practice time. Those were my early band experiences.

I also played in a band with my brother called Twisted Roots. It was basically Paul’s band and his songs. He was the ruler of that band. He threw me out three different times for various reasons that I don’t think were related to my bass playing. I think I’ve been thrown out of every band I’ve been in that wasn’t my band, and not for bass-playing reasons. Twisted Roots did record a set of things that is now out. There’s a single that is out and there is an LP that is out under Paul Roessler and Twisted Roots or something.

I had my own band, Sexsick, that was supposed to be an all-girl band. My friend, Michelle Bell—Gerber, as she was known to some—and this girl named Elissa Bello, a drummer who had been thrown out of the Go-Go’s because she wasn’t cute enough or something. I can’t say that for sure. I’ve heard such rumors. She was adorable by the way, so it doesn’t really wash. We practiced a lot, but didn’t play a lot of shows. By the time we did, Elissa quit or something, because we ended up with a guy drummer who had been in Twisted Roots as well. We sort of asked him to play with us.

My experience with all-girl bands is to not do it. My experience, specifically with playing in a band with other women, is that they don’t treat it the way guys treat it. To guys, it’s like work. The emotions are kind of taken out of it. It’s like, you show up, you practice—there’s no drama. With the girls it’s like, “I’m tired.” There was always something. It was somehow a big put upon to go to practice. I had been going to practice for years. I was buying practice time and stuff, and these girls were too tired or didn’t feel like it. It was really a bit disheartening, but we did do that for a while and we did play a few shows, but we never recorded anything.

![]()

I had just joined DC3 with Dez Cadena and a drummer. We were going to have a three-piece power trio. We were all excited about that. They practiced at the same place as Black Flag. Two weeks into that, I got a call from Henry Rollins saying, “Do you want to be in Black Flag? Why don’t you just stay after practice with DC3 and play with Bill and Greg.” So I did, and it was weird. After practice with Dez, I hung around and they acted like they knew nothing about it, but they were up for it. So we jammed, and they asked me to join the same night. I got an opportunity and I took it. I have no regrets about any of it.

I was still going to UCLA the whole time. I said, “If I do this, I need to finish.” I was three years into UCLA by then. This was 1983. I said, “I’ll take quarters off, but we need to work around my schedules.” I studied economic systems science, which is basically half economics and half computing and programming. My idea was that if I wasn’t in music, I could do computers, and there would always be jobs in computers. Of course, nothing I used in college really was that useful in the end. You just finish, because you do.

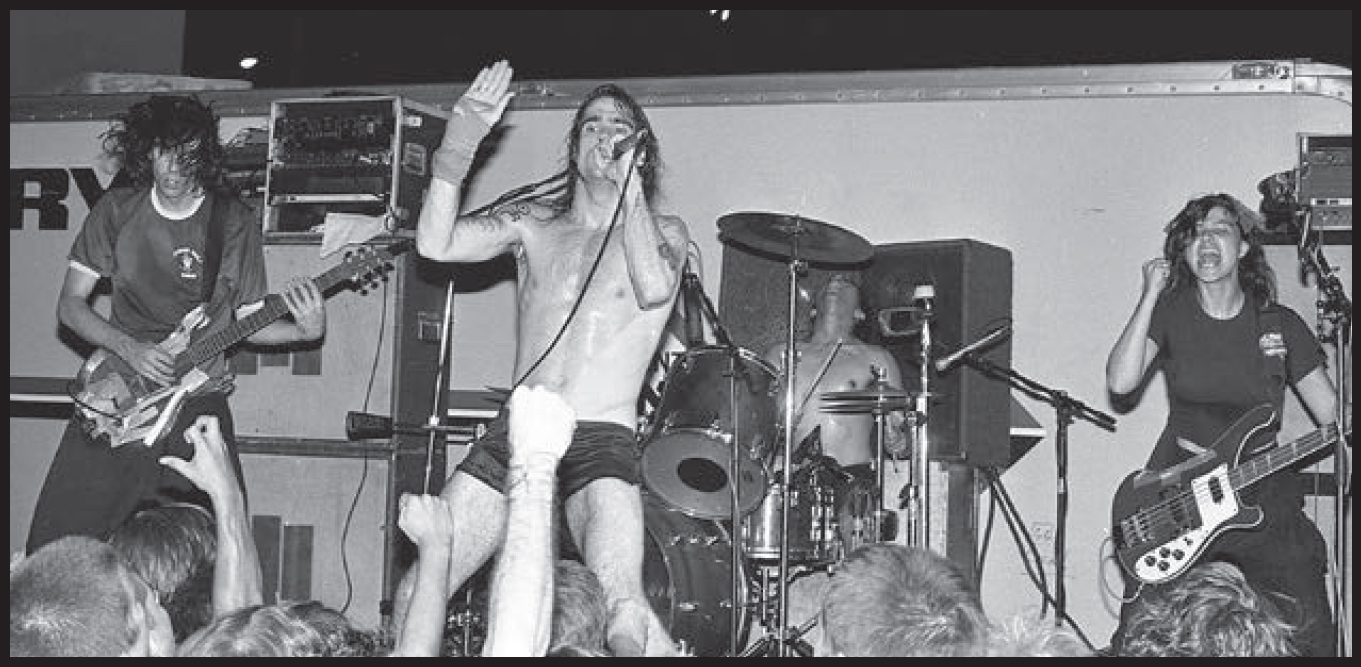

I was in Black Flag from fall of ’83 to fall of ’85. I did a bunch of touring and made a bunch of records and then I started in Dos with my husband-to-be and now ex-husband Mike Watt. It’s a two-bass band, and we have had this band now for twenty-seven years. He plays bass. I play bass and I sing. At times it is largely instrumental, but there is some significant amount of singing. I have another band that is more of a project that I do some singing in called Awkward, with a stand-up bass player, which is also a two-bass band.

I’ve also had a virtual band with roots going back to 1977. Glenn (the guitar player from Waxx, Visitors, and Monsters), my brother, and I have recorded material over the years, which is, as yet, unreleased. In the old days this was on cassette, including bouncing cassette to cassette in order to multi-track. These days it is done over the Internet, as Glenn lives in Ohio. In the early days, I was a much more minor participant. We are actually working towards some possible releases.

![]()

Billie Holiday has been very important to me from a young age. I cover her in Dos. She is, in some way, perfect. It does not matter what the style is in music. What matters is if it makes me feel, and she makes me feel. There have been others that make me feel, but she was sort of the first. I was so connected to her and her unrequited love songs. You could just wallow in your misery with her so perfectly. So she was big.

I had a very short Elton John phase. I saw him at Dodger Stadium. I think it was my first gig, when I was thirteen or fourteen. My brother got into prog rock stuff. I couldn’t really get into that. I sort of jumped over, more into Stones and Bowie. I had huge Bowie and Rolling Stones phases. This was before I got into punk rock. I was a hippie for about six months. It all happened really, really fast. It accelerated because I was young, and then I was into punk rock.

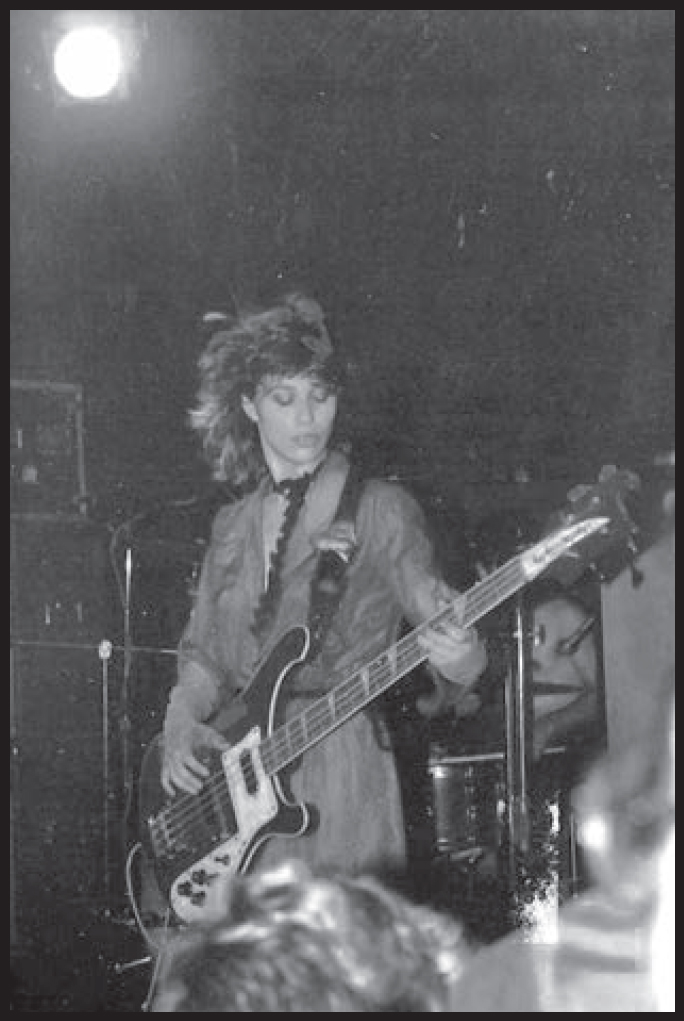

The Germs, obviously, they were friends of ours. I really loved them. I loved the Weirdos. I loved the Avengers from San Francisco. I think that might have started because I thought the bass player was really cute, but it did grow. The Avengers grew on me in other ways. They had a female singer [Penelope Houston] who had spiky, short hair, and she was a little bit tough. I was a tomboy from birth. When I was little, my school made me wear skirts, but my mom got me these cool skirts that had shorts underneath them, so at recess I could literally take the skirts off. I am a hardcore tomboy. I identified with Penelope—with guys in general, but with her.

I think it’s weird when I’m asked questions about being a woman, because guys don’t think about being guys. It’s kind of weird that women think about being women, but we kind of do and guys think about women being women, so I do get it. I understand why I’m asked the question, but my first thought is that it was never something I was really sort of conscious of. I was so much less of a girlie girl than all the girlie girls that I didn’t fit in with them. I would hang out with the guys. To get into gigs, my big thing was to hang out and move equipment at sound check so I could maybe get in free, because I was broke. I didn’t identify really with the girls in the scene.

The cool thing, though, in the early days of punk rock was that it was very heavily women. There were women who were powerful women who were on the covers of the fanzines, because they were setting the fashion trends. These girls weren’t even in bands. They just looked wild. I was sort of in awe of that. They were celebrities and they weren’t even doing anything, but looking incredibly punk. That was really cool and in that way, it was welcoming. Even onstage, you had a lot of women, especially bass players. The Eyes had a girl bass player. The Alley Cats had a girl bass player. The Bags had a singer and bass player. Practically every night at the Masque, there were women onstage. The truth is that it was happening before that. We had Patti Smith out there rocking it. People forget the Runaways. I tried to get into the Runaways at the Starwood when I was thirteen. They kind of laughed at me and told me to go away.

I was never intimidated. I never felt that way. When I picked up the bass guitar, my brother was in this prog rock band. They didn’t have a bass player. I was like, I’m going to practice really hard and get good enough. If I want to be able to be a good bass player, I can. I never felt like I couldn’t, and I never felt like it had anything to do with being a woman or not.

When the scene got a little bigger, you had this sort of influx of the South Bay influence. It did get a little less woman-heavy. You had a lot of guys with short hair who wanted to slam. It got a little less friendly. Pogoing was a lot easier and girl-friendly than slamming. So there was a sort of shift. You could call it violent. I don’t think that was the intention of it. They were just guys being guys. They were getting their rocks off banging into each other. They didn’t really care about the music. They could have done it anywhere. It just happened to be that that was where it was happening. I was there more to listen to the bands. I would never go to the Fleetwood, because it was just one of those clubs where you couldn’t watch the band. Basically, there was this huge pit and you could be plastered up against the wall. That’s no fun. So, it did get a little less friendly to women a bit later.

![]()

When I was in Black Flag, there were some difficult situations at times, but there were also a lot of people who thought it was really cool, so there were balancing factors. I had numerous different political conflicts as a result of the fact of me being the girl. It causes more friction than it should, because we’re human. I didn’t behave perfectly professionally and others didn’t behave perfectly professionally, so, sure, there were issues. But it’s almost like anything. You’re talking about a marriage of six to ten people. We’ve got road crew; we’ve got other bands. You’ve got this sort of microcosm happening. It’s complicated. You’re together all the time, and there’s no privacy. You’re exhausted and emotional and you’re away from home. You’re away from your emotional support. All of that stuff.

Black Flag certainly forced me out. That is just a statement of fact. As to why—they didn’t want to play with me anymore, I certainly played a part in that and they certainly had a part in that. I think, truthfully, Henry is in touch with how hard it was for him. Therefore, he’s more able to see that, of course, it was physically so demanding for me. It was trying to train for the Olympics. To Greg, it was never that way. It was never that hard for him. I get that, and I got it then. We’d practice until me and Bill would be dropping on the floor, and then Greg would go jam with someone else. Guitar is just easy, and Greg is just an animal. But physically, for me, I was just absolutely against the wall all the time. I think Henry understood that a lot, and Bill always was compassionate about that. Drums being by far the most physical, he went through a lot of that. We were always operating at full capacity. Pain. Exhaustion. Endurance. Max. I think Henry acknowledges what it is and was for me more sometimes than the others.

When it actually came down to it, Bill had been kicked out first, before the 1985 tour. He had been a strong supporter of mine. My behavior during the 1985 tour rubbed some people the wrong way. By the end of the tour, they had decided to throw me out. What the exact reasoning was could be anything, or just how I behaved on the tour. It could be they had a sense that they wanted to do that before, but they needed to do the tour. Or it could just simply be that me being a woman did create some difficulties in and of itself. They would never admit that, because they chose to have a woman to begin with. Although they may appear to be misogynists, I would say that’s not really who they were.

![]()

Of course the scene influenced me, because everything we experience influences us. In some ways it may have skewed my ego, because I was given some attention and level of importance that a lot of young people aren’t. That often comes with a backlash of realizing you’re just not important in the world. That’s part of just growing up and maturing, but it may have been a little harder adjustment.

It’s always interesting that today Black Flag is sort of a household name, so it will come out in a weird context. You see the look on someone’s face and it totally changes their view of you right there. Bam! It is usually positive. They’re like, “Whoa! You were in Black Flag.” And you’re like, “Yeah, and I’m the same person I was two minutes ago and that was thirty years ago.” But no, to them it’s like “Whoa!” It’s usually cool, but it also makes me feel old. I’ve done so much since. It’s like, “Really? That’s it? That’s who I am to you now?” It can be cool. It can give you some street cred with someone who’s got some walls up, who maybe drops his walls down. You earn a little bit of respect in some way, but it was a long time ago. When people make too big of a deal of it, then I think they’re minimizing everything that’s happened since. They look at you. Clearly, you’re not a punk rocker. It’s like, “Dude, do you have any idea of how much of a nonconformist I still am to this day?” I’m a total punker, but they don’t know what it is.

What it is to me is that I don’t conform to the rules, which means if you’ve got some rules about what punk rock is, I don’t fit it. I don’t want to fit it, ’cause that’s gross, because punk rock isn’t that. It’s not fast and hard and loud. Yeah, Dos isn’t fast and hard and loud, but it’s really punk, because how many two-bass bands do you hear? I’m constantly pushing the envelope, still. It’s frustrating in that way. You were this, but you’re not cool anymore. You’re a traitor, because you have a job or whatever. You know what I mean? It becomes a little bit frustrating if it gets turned into “You were only cool then.”

In a way I’m thankful that I was involved in it so long and so far from, in a way, the beginning. I’m not trying to make myself bigger than I am, but I was there and I feel like I’ve seen it evolve from such small roots to this resurgence that’s happening today. I’m able to sort of say I think I kind of know what is and isn’t punk. When someone tries to tell me the rules, I resist that. Being a tomboy at my core, I don’t fit in. I don’t fit with girls. I don’t fit with boys. I don’t fit with your idea of what punk rock is. I don’t fit with the intellectual crowd. I don’t fit in with the creative crowd that does movies. I’m a total weirdo to them, too. I don’t fit in anywhere. I worked in the corporate world for eleven years. Total weirdo there, too. Me and my dogs. We can relate to each other, but most people, I don’t relate well to. I think that’s absolutely part of this whole punk rock thing we’re talking about, because you don’t necessarily conform into it and go, “Well, if I just do xyz, then I will be more accepted.” It’s never been about being accepted.

I got into punk rock and I got to be, in a sense, validated. There are other people who sort of feel that way, too. Fighting the society. Fighting the disco at the time. And the hippies. Being anti-everything, it seemed. Because at the time, it seemed like that was okay. Sort of hating things was okay and that was kind of what I needed, ’cause that’s kind of who I was. I felt validated enough that I got to take of it what made sense to me. That was then, and I’ve moved past it. Not that I’ve moved past it [to the point] that I’m not a punker anymore, but I’ve incorporated that into who I am today. I still play. I still write music. I still do all sorts of things, and it manifests itself in this whole other way. That growth and maturity and change is normal and a part of being human.

I see a lot of people who are sort of hung up on those being the glory days. None of the music since then is any good, or whatever. And I say, no. Even if I have no idea about the new music, it’s me that hasn’t gone out and found the good new music. It’s out there. I’m convinced it is. It wasn’t better then. It may be what I knew then. I might have gone to more shows then, so I saw more bands live, and seeing bands live, you get that tactile experience of it. I’m sure you could get that today. It takes some work to be part of a scene. I’m sure there are scenes. It may be the fact that it was small [that] helped. I don’t buy the idea that that was somehow special and unique, because we were there. I’m glad I was there. I got some great validation, but I’m sure someone who’s a teenager today could do it. I don’t believe it was a unique, special time. And I don’t believe that being a woman was necessarily a unique experience that way. I’m merely saying that, from my standpoint, it was equal that way. And in some ways that’s the most important thing about being a woman—to feel equal and part of, and not feel put down or separated. We tend to feel ostracized by something that is a little bit male-oriented, and I don’t think that was. Sure, I had to get my hands dirty sometimes. There were some badass girls. You had to be willing to fall into some difficult situations, but that’s true in life, right? I mean, sometimes you need to stick up for yourself, and I don’t mean physically or [to] fight, but I do mean you have to pick those battles which mean a lot to you and stand your ground.