MY first aerial adventure was in the Annapolis gymnasium. I was captain of the Navy Gym Team which was out to win the intercollegiate championship of the year. In line with this ambition I devised a hair-raising stunt on the flying rings. My plan was to get a terrific swing, high enough to be able to count on an appreciable pause at the end of it.

I figured I could at this moment do what was called “dislocate,” which meant swing completely head over heels without changing grip, with arms at full length—unbending, forcing my shoulders through a quick jerk, that made it look as if they were put out of joint. In addition, I was going to make another complete tum, legs outside, letting go with my hands as my ankles passed my forearms, and catching again as I fell.

About a week before the big meet came off I mustered up my courage and gave this risky stunt a try. To my relief, as much as to my pleasure, I did it without breaking my neck.

The day before the meet the gym was crowded with people watching practice. As the contest would be close all hands were much excited. I felt secretly elated because I was sure my stunt would give us the points needed to win. Never before had I reached the altitude I reached that afternoon when my last turn came on the rings. I was conscious of the dead silence as I swooped through the air for my final effort.

With a quick whirl I “dislocated.” It felt all right. The next second I was spinning into the second tum. I let go; caught—but only with one hand. For an instant I strained wildly to catch the other ring. But it had gone. People afterwards told me a queer sharp sigh went up from the crowd at this moment.

I fell. It was a long way down even for a flyer. Luckily it wasn’t a nose dive. I came down more or less feet foremost. The crash when I struck echoed from the steel girders far above me, and there was a loud noise of something snapping. I tried to rise, but fell back stunned. The effort told me though, that I was far from dead. I noted there was no feeling in my right leg. I glanced down as willing hands came to lift me and saw that my ankle and foot was badly crumpled; the same foot I had broken playing football against Princeton.

My team not only won the Meet next day without me, but captured the intercollegiate championship to boot. Never again, I felt, would I attach any undue importance to myself.

That was December 1911. I missed the semiannual examination. I was due to graduate in June. For five months I wrestled with nature on one hand and with the spectre of academic failure on the other. The Navy made no allowances for me and wanted me to go back a class. After a great struggle I managed to graduate. I don’t believe I could have pulled through but for my great desire to go out in the fleet with my classmates. They were a very splendid lot and it made me rip-snorting mad whenever anyone suggested my going back to the next class below us. But I was still—confidentially, of course,—something of a lame duck. The bones in my foot and leg had all knit but one. The honey knot on the outer side of my right ankle was still in two pieces. It clicked when I walked. Someone told me if I walked a lot I would grate the fragments together and induce flow of osseous fluid. I did this for weeks. It hurt; but it apparently worked.

This terrific struggle I had made to graduate taught me a great lesson—that it is by struggle that we progress. I learned concentration during that time I never thought I possessed.

Five futile years followed. Futile in the sense that they contributed so little to my life’s work, aviation. My game leg was a nuisance. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t. Long hours of watch-standing aboard a man-of-war proved too much for it. Certain kinds of deck duty left me aching all over from the pain that began in the old mangled ankle. One day, after I had fallen down a gangway the surgeons decided to nail that last knob of bone together. For some time I thought they used a silver nail and felt set-up by so precious a finish to my anatomy. But when I found it was just a plain old-fashioned galvanized nail they had used I lost even that thrill.

The Navy regulations would not allow my promotion on account of my injury. I was retired on three-quarters pay; ordered home for good. Career ended. Not enough income to live on; no chance of coming back; trained for a seafaring profession; temperamentally disinclined for business. A fizzle.

Then war. War did a lot of things for a lot of men. In a sense it saved me. For a willing cripple suddenly became to a mad world as valuable as a whole man who might be unwilling. Washington used me to mobilize the Rhode Island State Militia. Thence I was promoted to a “swivel chair” job in the Navy Department. I transferred enlisted men from station to station, and official papers from basket to basket. Secretary Daniels added me to the Commission on Training Camps as its Secretary. There I came in close touch with Raymond B. Fosdick, Chairman of the Commission, one of the most brilliant men with whom I have ever come in contact and as agreeable as he was brilliant. This gave me a bigger desk and deeper baskets. But I didn’t want furniture; I wanted to fight.

For several years I had known my one chance of escape from a life of inaction was to learn to fly. For years I had wanted to fly but my leg and obligations had prevented. Now that even willing cripples were looked upon to do their bit perhaps I would be permitted to fly. But the doctors said, “No, not with that leg.” To which I was impelled to burst out angrily, “But you don’t fly with your legs!” Only I didn’t; I’d been schooled never to do any bursting out.

After a while desire got the better of my schooling. I lost twenty-five pounds worrying over the useless-ness of what I had become—just a high-class clerk—when I had been trained to go out and fight—fight wind and seas and the country’s enemy. And here I was, a big desk, deep baskets, reams of official papers, and I still in my youth. Hundreds of army and naval officers were chafing at swivel chair jobs. By conspiracy I went up again before the medical board. “You’ll have to take leave, Byrd,” they said. “You’re in terrible condition.”

Truly I was on the verge of a breakdown. In addition to my worry I had worked day and night to help organize the Commission so that I could fight and fly—(do my duty. Yet that short half hour in the Board Room was the turning point of my life.

“Give me a chance,” I begged them. “I want to fly. Give me a month of it and if I don’t improve to suit you I’ll do anything you say.”

They were sports, those surgeons. So does war do away with much of the vexing formality of peace. They decided to give me one short month of my heart’s desire. Ultimately they gave me two. Fresh air, zest of flight, the deep joy of achievement, compounded a tonic that fattened and strengthened me at once., When the time came I passed all tests with flying colors, was pronounced in perfect health and have been so ever since. Surely a feather in the cap of aviation, this quick cure of a rundown man. Moreover, I haven’t been off active duty since.

I was ordered to Pensacola for instruction. This was the fall of 1917. Congress had declared War. The country was seething with excitement. Our first destroyers had gone over to join the British Grand Fleet. Every edition of the newspapers was full of gory horrors. The Western Front was one grand riot of organized murder. I reached Pensacola ready to loop-the-loop that day if national emergency required.

Glistening Florida sunshine brought all the details of the station out in sharp relief. Men in whites and in khaki were hurrying to and fro. Big open hangars gaped like reptiles that had disgorged the birds they had swallowed and found indigestible. The birds themselves—navy seaplanes—were drawn up along the sea ramp; some were in the water; some roared overhead. Men were hauling them up and down, starting engines, taking off and landing. A hive of activity, typical of the thousand military hives buzzing about the country.

Brilliant sunshine; such blue water. And how full of eagerness all the men seemed. The picture stamped itself on my mind.

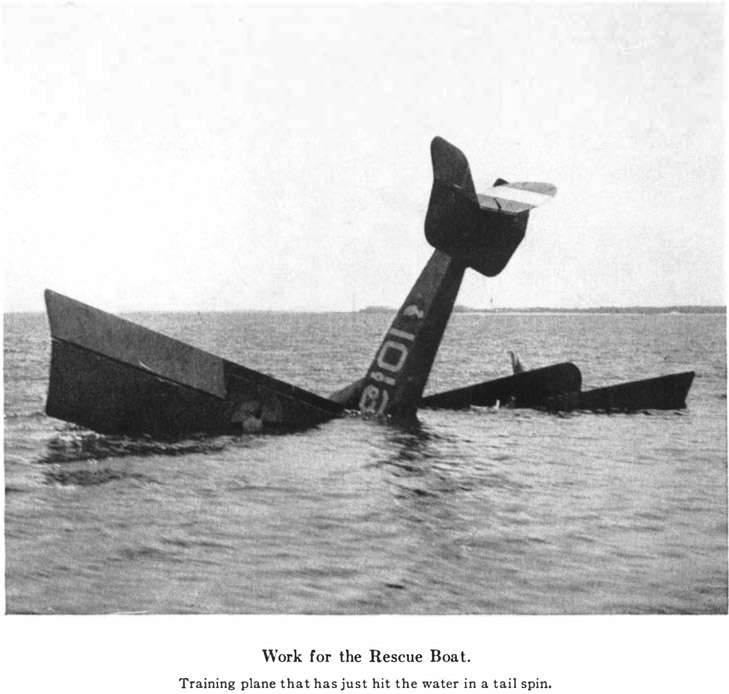

Something attracted my attention; a shout, or an uplifted hand. I glanced to a training plane in the azure sky above me. It wobbled as I looked. It hesitated, dipped, then dove straight down. It came leisurely enough at first. I didn’t realize its seeming lack of speed was due to its great height. Soon it was dropping like a plummet. Tail skyward, it plunged into the Bay. Across the still water came a terrific crash. I stood rooted to the spot, horrorstruck.

A speed-boat dashed out toward the wrecked plane. On its deck, ready for their gruesome task, I saw stretcher bearers, surgeons and divers.

The tail of the wrecked plane and a part of one wing protruded from the surface of the water. Pilot and student were caught in the wreckage below, both unquestionably dead. The speed-boat drew alongside. Divers splashed overboard with pliers and wrenches. In twenty seconds one emerged dragging a limp form after him. I think I must have held my breath while the rescue party struggled for the other flyer. Finally the boat shoved off. Some one near me said in a low voice, “The wrecking barge’ll have to get it.”

“It.” So that’s what you were after a crash! Just a body. It!

I felt downhearted.

After a while I walked away. Perhaps I’d get used to it. Suddenly I was grabbed from behind. The thought flashed through my mind that perhaps I’d been asleep and had had a nightmare. Now some one was waking me up.

“Hello, Dick Byrd!”

It was my old friend and classmate, Nathan Chase. He paused in the middle of his greeting. I suppose my face revealed more than I wanted it to. “Don’t mind that,” he said and nodded toward where the wrecking barge was moving up to the wreck that contained it.

“Have ’em often?” I asked him.

“Oh, every day,” he said. “Sometimes two or three times a day.” Then in the next breath: “Want to go up, old man?”

I’m frank to say that was not the moment I would have selected to go up. I hadn’t suddenly lost my nerve. Nor had I changed my mind about becoming an aviator. All the prime yearning for action was still in me. I was just temporarily nonplussed. I’ve since learned what the feeling means. And I’ve found that the best antidote for it is prompt and vigorous action.

Chance had given the action I needed. Still in a bit of a fog I presently found myself wearing helmet and goggles. A plane stood nearby with its engine turning over. Evidently it had been got ready for Chase. Before we climbed in Nat handed me some cotton.

“Stuff it in your ears,” he shouted. “You’ll be deaf if you don’t.”

Mechanically I did as I was told. We were in line with the barge grappling for the wrecked plane just ahead of us.

The plane was exactly like a land one, except that its wheels had been replaced by a pontoon which now rested on a truck. When we had taken our seats mechanics pushed the truck down a concrete ramp into the water. As our pontoon floated Chase gave her the gas. We skidded thunderously away and swerved into the wind for a take-off. I felt the whole body rear back and spray flew high all around us. Gradually we assumed an even keel, the spray lessened, waves began to slap bumpily against the bottom of the float. We were in the air.

My pilot pointed to an instrument in front that read in hundreds of feet. I gathered this told our altitude. When the pointer read 4,000 feet he turned and smiled at me. Fortunately I could not interpret this sign and the motors prevented talk. As a result I had a few seconds more of reasonable complaisance before the worst began.

I suppose Chase knew how I was feeling about the fatal crash I had just witnessed. The medicine he chose was to go through all the stunts he knew. And stunting in those days, years ago, wasn’t what it is today. We had a cumbersome seaplane under us, too.

We dived and rolled and slipped. We did a tail spin until I could almost see the rescue boat on its way out to us. There weren’t even names then for some of the things Chase did. For minutes I couldn’t tell which was sea and which was sky.

Suddenly we came out of a spin. He nudged me with a nod towards the stick. The next instant I realized I had control of the plane. That was Nathan’s idea of a joke on me. The responsibility cleared my brain. It was perfectly idiotic for me to try to fly. I knew that. But this was no time to argue. I managed to keep our course straight ahead; nothing but common sense. But soon we were headed downward, judging from the roaring of the engine and the wind singing through the wires. I glanced at the altimeter; it showed a loss of a thousand feet already. Luckily Chase took her back before it was too late and brought us safely to earth.

I do not recommend such a method as a means to teach the novice. True, the passenger is more likely to grow dizzy than the pilot, for responsibility and the effort to control the plane have a steadying effect. Further, the pilot knows at all times in just which way the plane is going to dip or swing and so automatically prepares himself for the centrifugal forces set up. But too sudden a plunge into piloting may dampen the candidate’s ardor.

My training now began in earnest, groundwork as well as flying. I remember taking apart my first airplane engine. The vast number of cams, valves, rods, screws, bolts and other pieces fascinated me. They all seemed so dead, so unrelated when spread around on the greasy canvas at my feet. They were dead. To the novice they were as meaningless as so many cobble-stones.

I remember that same afternoon we reassembled the engine. The mechanic with me became a little feverish as we neared completion of the job. At first I thought he had the knock-off whistle on his mind. He puffed and panted over a Stilson wrench; he cut his finger and let it bleed unnoticed. … The whistle blew. He seemed not even to hear it.

We finished. A small crane panted up and swung the engine into place. Suddenly I had a streak of apprehension across the back of my neck, as if I had been touched with a cold finger. Did we have all the parts in place? Would the engine run? Would it hold up the plane? Would it live?

The moment came. Tired, greasy, silent, the mechanic and I stood and watched our engine roar into life, the plane it pulled slide across the field, crop the daisies and soar into the blue.

In that moment a new understanding of aviation came into my life; in watching that plane rise, fly, devour space, I felt that I had helped create something alive; I had contrived a creature that by widening the vista of human life and quickening the processes also thereby lengthened life; that by conquering the forces of wind and gravity had added to man’s triumph over Nature.

I made my first solo flight after about six hours’ flying with an instructor. I had got the “feel” of the plane and was now confident that I could do as well alone as with the licensed pilot along. The rub was whether I would know how to handle my machine if trouble came.

First flight alone is probably the greatest event in an aviator’s life. Never again does he feel the same thrill, the same triumph, as when he first eases back the controls and lifts his airplane clear of all natural support. Then there is that special and extra little sensation when one banks and lands alone for the first time. It is at this point that the new hand so often loses his nerve or lets his judgment slip and crashes. Nowadays such accidents happen less frequently. Much more instruction is given before soloing. But in the war I have known new pilots to hop off alone with less than three hours in the air.

“Twenty minutes flying is enough,” warned my instructor, Ensign Gardiner. This was the usual warning given on account of the strain of the first solo hop. As my plane was shoved into the water I glanced back. The poor fellow could not hide his anxiety. I knew he felt that if I lost my life it would be as much his fault as mine.

As the machine bobbed up I shot my throttle wide and pulled the controls back to ride high on the waves. When I had some speed I shoved the controls forward again to make the float coast. A minute or so later I figured I could lift. With a fine feeling of elation I took off.

For what seemed a long time I flew straight ahead. It was too good to be true. I was flying at last. I glanced down at the water. It looked dark and sparkling in the fresh seabreeze just picking up. The station seemed very hard and dead by comparison. Quickly I glanced back at my instruments. Nothing was wrong yet.

I began to think what I’d do next. I concluded that I should try some landings. After all, if I could land safely I might then call myself a flyer. Any one could get a plane up into the air. I nosed down gradually. But when I leveled off I was going too fast. As it had been drummed into my head not to lose flying speed, I was taking no chances. I struck the surface with a big splash and porpoised—that is, leaped out—some distance beyond where I hit. But I didn’t smash anything, which was a comfort. I tried three more landings in quick succession. In all I kept at it for an hour and twenty minutes on that first flight. Gardiner got pretty worried about me. But when I finally taxied up to the landing I felt a confidence that was the pleasantest sensation I had ever known. The big thing about flying is to come down safely.

As I came alongside the mechanic in charge of my plane called out to me: “ How’d she go?”

“Couldn’t have been sweeter,” I told him.

Instantly his rugged face melted into the sticky satisfaction of a man who has inherited a million dollars. And right away he began to nuzzle his engine like a mother cat who’s just taken her own blood back. The Commandant happened along at that moment. “Attention!” barked some one, “according to Hoyle.” It was a secret joy to me to see the ill-concealed scowl of impatience on the mechanic’s face. I knew at last how he felt. I had flown; had come down safe; I had him to thank for an engine that kept on running. What was military frumpery beside that?

In the ensuing period of my training I specialized in landings. I made hundreds a week. I made them from every altitude and in almost every position the plane could assume, with and without power. I tried stopping the engine suddenly a few feet above the water; again in the middle of a bank; and sometimes in midair well up. I knew an engine failure was far more dangerous at fifty feet than at 5000. I wanted to be prepared. I found out at what angle I could climb and get down without a tail spin in case my engine stalled. I landed on smooth water and on rough waves. I found both difficult. Over glassy water it is hard to find the surface. All this practice saved me from at least three fatal crashes in the early weeks of my flying, and a number of times since then.

As I progressed the fundamentals were continually being dinned into my head. I grasped that I must not try to stunt under 3000 or 4000 feet; that I must keep high enough, if possible, always to be within gliding distance of a landing plane; to be certain to keep the flying speed of the plane at all times; to keep a sharp lookout for other planes; always to land into the wind.

I learned that the majority of casualties, outside a stalled engine, came from the pilot allowing his plane to lose its flying speed. I learned first-hand that when this happened the plane stalled and dropped promptly into a nose dive, or dropped backward into a tail spin. (This dangerous speed I found to be different for different loads on the same plane.) If on a bank my plane sideslipped and then went into a tail spin.

With the other young pilots I learned that such stalls are generally caused by climbing too rapidly, by making a bad turn, or gliding down at too flat an angle. I soon found that if the turn were not properly made the plane would skid from centrifugal force just as an automobile skids on a slippery street.

After I had made the grade with single pontoon planes I took some lessons in the twin pontoon type and in the big flying boats. In the latter there is no pontoon of any sort. The fusilage is a big boat in itself. Crashes in these machines were the worst because their engines were above and behind the pilot, smashing down on him if the plane made a bad landing.

When my time came for land machines they proved easier in several ways. The chief difference lay in the fact that one can judge distance and landing speed so much better over land than over water.

When the Navy Department through the Commandant, handed me my pilot’s wings and a clean bill of health I was sitting on top of the world. Furthermore, the galvanized nail in my leg seemed to be holding tight.