ON my way to Washington I learned to my surprise that the Navy was going to tackle the Trans-Atlantic flight after all. The news was enough to play havoc with my reason for the moment. I didn’t even stop in Boston to see my people who were ready to welcome me after my “arduous” war experiences.

The minute I hopped off the train at Washington I rushed right up to the Navy Department to get the latest report. I got two reports. The first, very exciting, was:

“Captain N. E. Irwin, Director of Aviation, is recommending to Secretary Daniels that Commander J. H. Towers be placed in command of the Trans-Atlantic flight which is to go through at once.”

This meant the party was bound to go through. I felt like going out behind the big white building and shouting for joy.

Then I got the second and, to me, crushing report:

“No officer or man who has had foreign duty will be permitted to be a member of the Trans-Atlantic flight expedition. This includes those who have been on Canadian detail.”

I was stunned. I knew that one motive behind this ruling was to give a chance for excitement to some of the poor devils who had fought the war behind their desks in Washington. Yet wretched months at Halifax were to deprive me of realizing my dream. I confess that the wave of bitterness that struck me over this seeming injustice was almost beyond control. It was some time before I could honestly and coolly say that “after all, the important thing is for an American Navy plane to prove that it can first fly the Atlantic Ocean.”

I suppose the blow was greater than I realized at the time. Two days later I came down with influenza bordering on pneumonia. The day after I passed my crisis another officer was brought in and placed beside me.

This was Lieutenant Kirkpatrick, Captain Irwin’s aide. “Hello, Dick,” he greeted me, “I suppose you know the Captain has just directed your transfer from Washington to duty at the Pensacola Station.”

I could scarcely believe my ears. “Is the big flight off?” I gasped. It was the only possible thing, I thought, that could account for such orders. Surely the authorities could not be so unjust as to ship me away after I had worked for a year on the idea.

“No, I should say not. But the Commandant down there has asked for you to come as his aide. You are not available for the NC flying boat on account of your war duty. And I gather you have finished most of the navigational plans. Don’t you like Pensacola? “

Feeling as if I should faint I staggered to the telephone and called up Towers. “Do you still want me to help out on the flight?” I asked him weakly.

“Decidedly so,” was his prompt reply.

As soon as I had enough strength I went to Captain Irwin’s office and “went to the mat” with him on my Pensacola detail. The captain is a huge man, over six feet and built like a prize fighter. I suppose I was a pallid-looking object as I wavered before him, putting my cause quietly enough but in words that were loaded with dynamite—for me. I can’t say I won. Rather the Captain decided to have a little mercy. My orders were cancelled.

Just before I left the hospital an incident occurred that I had good cause to remember later. Near my bed was Lieutenant-Commander Emory Coil, a classmate and close friend of mine, who had been desperately ill with pneumonia. One morning, when he was so weak that he could still barely lift an arm, I saw him reach for a paper that had been left near him by mistake. He wasn’t supposed to read. I heard a groan. Coil had gone even whiter than before. The paper contained an item describing the death of the poor fellow’s wife and mother. This was his first knowledge of the catastrophe that had befallen him.

Twice more was the path of my life to cross that of Emory Coil’s, each time under the shadow of disaster.

Josephus Daniels, Secretary of the Navy, gave his final official approval to the Trans-Atlantic flight project on February 6, 1919. Eight of us were then formed into what was called the “Trans-Atlantic Flight Section of the Bureau of Aeronautics.” We were in accord on the general plans; but I held out on one point. I did not believe it necessary to put warships every fifty miles along the route. I had had enough experience to believe that the pilots could navigate a straight course without depending on station ships.

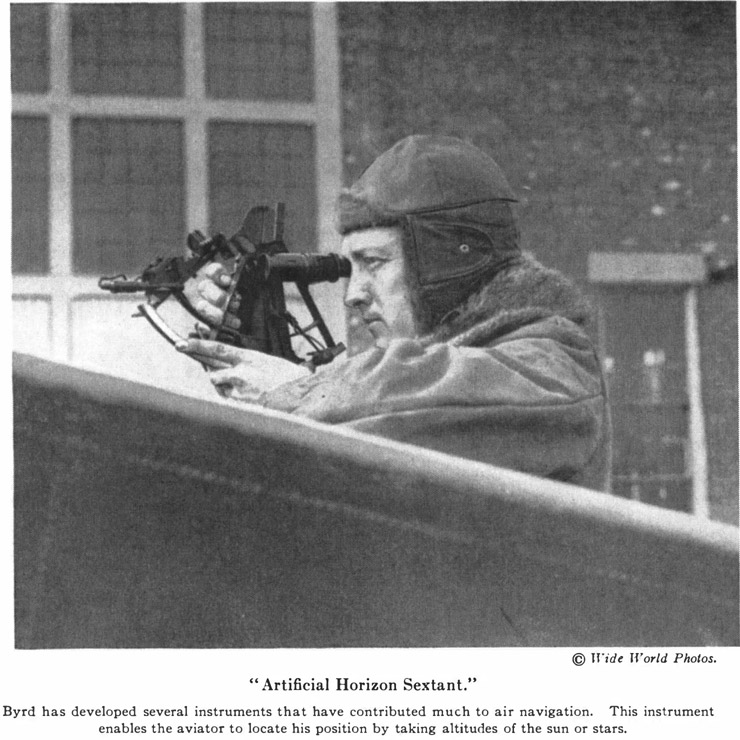

At the time there was still no proper instrument to measure the amount the course of plane should be changed to allow for drift. A wind blowing forty or fifty miles across the course would soon carry a plane far out of line unless her pilot corrected for the error. This was but one of the problems I had on my hands to solve during the three months left before the planes hopped off.

Red tape was cut at every opportunity. Bureaus of Ordnance, Navigation, Construction and Repair, and Operations were all subordinated at times to help us get ready. Such co-ordination runs smoothly enough today. But in 1919 the Aviation Office was still looked upon as an ugly stepchild by the balance of the Navy Department. Mr. C. B. Truscott of Aviation turned out the final design of drift indicator. The Chemical Section of the Bureau of Ordnance devised bombs and flares. Mr. G. W. Littlehales of the Hydrographic Office, a mathematical genius, evolved for us a short method of navigation. And so on.

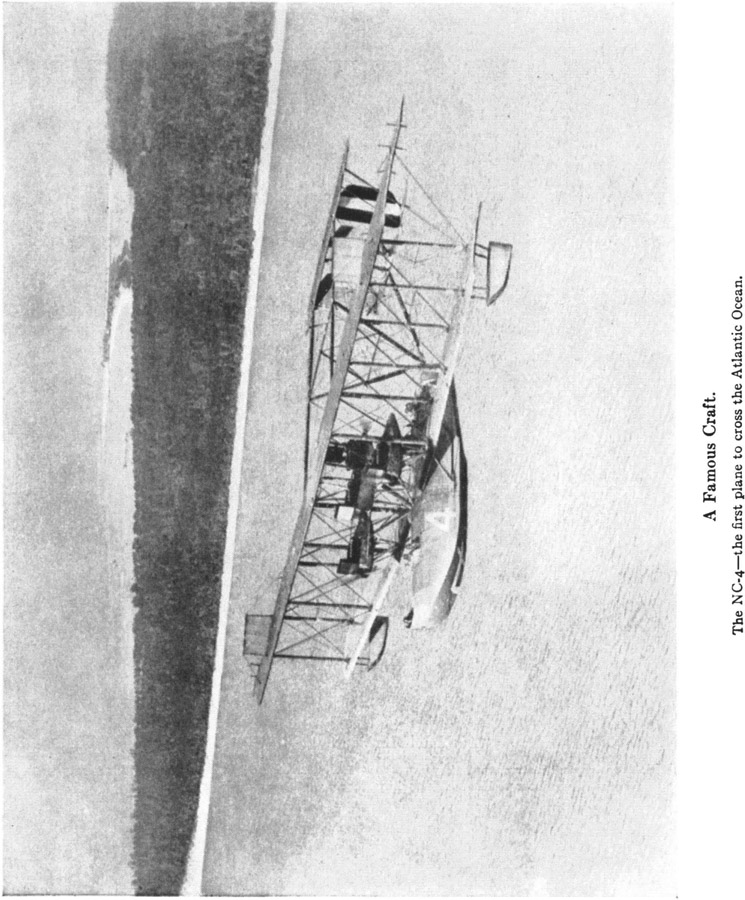

By April 21 the Trans-Atlantic Flight Section was moved to the Naval Air Station at Rockaway, Long Island. Two other NC boats had been built. So now we had a group of three, the NC-1, NC-3 and NC-4. The last named was fated to be the first flying machine to cross any Ocean on Earth.

These NC boats would even today be considered very large craft. In fact, there is no plane in the States today with so great a wing spread. Wing spread of the upper wing was 126 feet. If laid on top of one of our largest Pullman coaches it would extend several feet beyond it. The overall length of the boat was 63 feet. Each was equipped with four Liberty engines, making a total of 1600 horsepower, over thirty times the aggregate of the average automobile. I know of no other plane today, nine years later, that is more highly powered.

The total weight of an NC boat was 15,100 lbs. including radio. Its weight with full load was about 28,000 lbs., or over five times heavier than the Bellanca monoplane which recently broke the world’s endurance record. Our economical cruising speed was about 75 land miles per hour. We estimated the cruising radius with full equipment and emergency gear and crew of six men, to be 1,475 miles.

The NC type of flying boat was not a step forward in aeronautical design. It was a whole jump. Such sudden departure in the design of aircraft is rarely wise. But in these ships the Navy had access to the best design brains in the world at the time. Among them were such men as Glenn Curtis and Naval Constructors Richardson, Westervelt and Hunsaker.

One day fifty-one men, including the pilots, were crowded into the NC-1 and it was successfully taken into the air!

On May 3, 1919, the three NC flying boats were regularly placed into commission. To the best of my knowledge this was the first time in history a plane had been given official individuality like a ship.

Each plane carried a commanding officer who also navigated, two pilots, a radio operator, an engineer and a reserve pilot engineer. Commander Towers took command of the NC-3, using it as his flagship. Lieutenant-Commander P. N. L. Bellinger took the NC-I. Lieutenant-Commander A. C. Read had the NC-4. Three better men could not have been selected. Towers was a student, quiet and reserved and methodical; Bellinger a rugged seafaring type with sanguine temperament and a likable nature; Read, was slender, and uncommunicative, though nothing missed his sharp eyes and quick brain.

As the weeks flew by a thousand new details of preparation seemed to crop up every day. There were complications with the State Department in getting permission to land on foreign soil. Navigational instruments and methods we had evolved had to be given special tests. We made flights for measurement of fuel consumption. Careful plans were laid for communication with the ships that would cover our course. Fuel depots and repair stations were prepared up the coast. Radio tests were made a matter of routine.

On May 8, 1919, we were ready for the first ocean crossing by air in history.

I was to have a taste of the early flight after all. Through the efforts of Towers I was permitted to go with him in the NC-3 to assist in the navigation and look after the navigational instruments in the first two legs of the flight.

Just before we left several distressing events tended to mar the joy of getting away. On a trial flight with the NC-4 we got back to the beach just as the wires to the up-and-down rudder carried away. Had this happened in the air we should all have been killed. The day before our departure I heard a scream from a lady visitor to the station. Following her eyes I saw an HS-2 flying boat tail-spinning towards a big gas tank nearby. It crashed squarely into the structure and killed both occupants. A few hours later Chief Special Mechanic E. H. Howard, Engineer of the NC-4, while working around the plane accidentally stuck his arm into the propeller and had his hand cut off at the wrist. He calmly grabbed his arm and walked to Sick Bay.

This series of accidents were said by local pessimists to be a sure sign of the fatal outcome of our flight.

At 10 A.M. on May 8, 1919, we left the water in the NC-3, with the NC-1 and NC-4 taking position on either side of us. For the first time a division of seaplanes, regularly commissioned, was underway with orders to fly across the Atlantic Ocean. For the first time in history airplanes were to navigate out of sight of land just as a transoceanic steamer must do without land marks to go on. Could we do it? We were flying into the unknown.

The roar of our four engines was terrific. Of course, we were used to it. And we were stimulated by the excitement of being off at last. But I think our attention was riveted more on the thunder of our engines than on any other single factor. Reliable power plants were not so common then as now. And if ours failed we must fail with it.

Towers wrote of this part of the flight:

“Byrd spent the afternoon vibrating between the forward and after cockpits, trying smoke bombs, sextants, etc. My cockpit was not very large, and with all the charts, chart desk, sextants, drift indicator, binoculars, chronometers, etc., stacked in there, very little room was left. As I wore a telephone all the time, wires were trailing all about me, and Byrd and I were continually getting all mixed up like a couple of puppies on leashes. Occasionally one of the pilots would come forward for a cup of coffee and a sandwich, or to take a look at the chart to find out how we were progressing. All these little festivities were rudely broken up about the middle of the afternoon when a squall hit us.”

That squall Towers spoke of did not bother us. We headed down through it. Just before it struck us we received a radio from Read saying that the NC-4 was having engine trouble, was running on three engines and would probably have to land. When Read began to drop astern and descend and Towers thought that the NC-4 was landing close to the destroyer, that had been stationed on our route, we proceeded on our course with the NC-1. The destroyer at the time was still visible to us. However, it turned out later that Read missed it.

As we passed the coast of Newfoundland I was not surprised when Towers wrote me a note saying, “This is fearfully rough air.” I already had been flying around that rocky coast and I had learned there are no rougher air conditions anywhere else in the world.

We reached Halifax Harbor at 7:00 P.M. Rockaway time which was 8 :30 Halifax time. The first leg of the great hop of 621 statute miles was successfully completed. It had taken us just nine hours to do it. It was very pleasant to me to be landing near the naval air station I had erected in the previous autumn. I was more pleased the next day when that station was able to be of some benefit to our expedition. We had made an early morning inspection of the NC-3 and found several cracked propellers. The base ship, the U. S. S. Baltimore, which had been sent ahead, had some spare propellers on board but no hub plates. I remembered that I had turned over some of these hubs to the Canadians. Jumping into a speed boat I found them still on hand.

Between Cape Cod and Nova Scotia we had for the first time in history done some real out of sight of land navigating in a seaplane and had been successful. Another test lay ahead of us when we left Halifax with the NC-1 for Trepasse, Newfoundland, the following day at 12: 40 P.M. Soon after we got out of sight of Nova Scotia the wind drift indicator showed that we had a sudden and big change of wind direction. If this were correct, it would necessitate a change of course of a number of degrees. Here was a real test of this instrument. When I asked Towers to take a sight on the water with the indicator he got the same result that I did. Luckily we had the courage of our convictions and changed our compass course accordingly. When we hit land exactly where we hoped to, we knew that the first drift indicator had proved its worth. And, I knew then that at last an airplane could be navigated without land marks. I was delighted.

As we flew along Newfoundland at about 5000 feet it was bitterly cold. A lot of white objects began to appear below which I at first took to be a fishing fleet under sail. When I looked down with my binoculars, I saw that the objects were icebergs, hundreds of them. They made a beautiful sight. I was getting thrills enough at the moment; but I wonder what they would have been had I known then that almost exactly eight years later I should be flying over the same area with thick fog covering everything, having flown all the way from New York without a pause, having still ahead of me a non-stop flight of 2,600 miles and with the lives of three shipmates and friends in my care.

I was numb from cold. The icebergs a mile beneath us did not add to my feeling of warmth. I was thinking how pleasant it would be to warm myself before one of our Virginian log fires, when suddenly I saw smoke coming towards me from aft. It looked for a moment as if I were going to get more heat than I wanted. I hurriedly wrote a note to Towers saying the plane might be on fire. I then crawled aft to try to get at the flame. To my great relief I saw that the smoke was coming from a cigarette McCullough was smoking.

Suddenly my head struck the top of the navigator’s compartment and several articles flew upward out of the cockpit. I felt as if gravity were acting away from the earth instead of towards it. We had struck a terrific down current of air which caused us to fall faster than gravity would have taken us. I was afraid that Towers was going to fall out of the cockpit. When we got settled again he handed me a note which read “roughest air I have ever felt.”

Soon we were gliding down into Trepassey Harbor. In a few minutes we could see our mother ship, the U. S. S. Aroostock, anchored beneath us and the NC-1, which had landed ahead of us, tied up alongside of her.

Up there on the dismal coast of Newfoundland, the Director of Aviation, with his rules and regulations, seemed a very long distance away. Feeling that Towers and Bellinger wanted me to go on the flight, I had hopes that I might still be one of the lucky ones. But soon after our arrival Towers handed me a radio from Captain Irwin which specifically directed that I should not accompany the expedition. My Nemesis was still on duty.

My gloom was broken by a strange diversion. Sudden telegraphic orders came for me to report for duty in connection with the dark horse of the Trans-Atlantic flight: the tiny Navy dirigible, the C-5. My duties would be primarily concerned with navigational methods and instruments of the C-5. I was further directed to do all I could for the C-5 in regard to navigation.

The C-5 was a fragile non-rigid gas bag of only about 200,000 cubic feet capacity, or only about one-tenth the size of a modern airship. While we had been flying north in the big planes she had been in the air on a non-stop flight from Long Island to St. John’s, Newfoundland, a world’s record for a dirigible of this type.

I was reading the dispatch over for about the sixth time and trying to collect my thoughts when one of my friends who knew of my long series of disappointments over the NC flight said: “There’s your chance, Dick.”

“You think the C-5 will make it?” I asked him.

“Sure of it. As long as she has gas in her bag she’ll stay in the air. You can drift over if you don’t do anything else.”

I didn’t have the heart to bring up the point that if there were any adverse winds they would take us away from land. I grasped at this straw. Perhaps I would fly the Atlantic after all!

Further, Emory Coil,, the one who had been in the hospital with me and read about the death of his wife and mother, had recovered and was now in command of the C-5. I had already turned over to him before I left New York all our navigational data and one each of the instruments we had developed for the big flight.

Now began a brief but exciting period for me while I nursed my last thin hope that I might still be in one of the aircraft to cross the ocean. There would be a fine chance to get some real scientific data with the C-5. Two of the NC boats were ready to start, those of Towers and Bellinger. The weather was right. But Read on his way to Trepassey, where we were, had been forced to land off Cape Cod. Now he was waiting there weatherbound. The C-5 was just around the corner from us at St. John’s. If I got away and aboard her, and she flew, there was still a chance that the miracle for which I hoped might happen.

At sea fifty warships patrolled the course the NC boats were to take. The press of the country was beginning to growl at the expense of keeping so many vessels at sea, now that war was over.

On May 15th, the NC-1 and NC-3 were about to take off when a speck appeared in the sky far to the south of us. It turned out to be the NC-4. Had Read been an hour later he would have been left behind. I grabbed a boat and rushed over to congratulate him. He had had a hard trip. When he had fallen behind us one engine had gone out of commission, then another. As the two engines left were not enough to keep the heavily-laden plane up he had to come down at sea. A sextant observation told him he was 100 miles off Chatham, Mass. With his good engines he taxied westward reaching Chatham next morning at daybreak. At least he had proved the seaworthiness of the new planes.

One of Read’s sentences stuck in my mind: “Not far from Trepassey I saw an airship headed out to sea,” he said.

Could it be that Coil had gone?

The mystery was solved a few minutes later when a radio was passed around: “The C-5 has broken loose from her moorings in a storm and blown away with no personnel aboard her.”

My last chance gone!

But I could not forget that this was the third blow Emory Coil had suffered this spring. However, fate was not yet through with my gallant and unfortunate friend.

Towers sportingly decided to wait until Read was ready. The situation was pretty critical due to the presence of the foreign contestants for first Trans-Atlantic air honors. British Captains John Alcock and Arthur Brown, R.A.F., were there with their little plane all ready to start. Lieutenant Commander Grieve R. N. and H. B. Hawker were also grooming to hop off for Ireland or England. As both had single-engined planes we felt they were taking big chances. Engines were not so reliable those days as now.

Of course Trepassey was now infested with journalists and photographers. I think that, despite their usual bland indifference to sensation, they were every bit as excited as we were over the prospect of making air history.

On May 16th the weather was reported still to be good. Read was ready. Our English rivals were not quite in shape. The great moment had come.

Weary I climbed the hill behind the rough field and sat down to see the take-off. To be here on the spot and see three planes hop off for Europe for the first time in history and, after all my hopes and work, not be in one of them, was a cataclysmic actuality that no amount of philosophy could efface. My depression was tempered only by the fact that our navy was doing the great job.

After three trials all the planes got into the air, led by the NC-3. A sharp wind cut down from the arctic regions not far above us and the blue sea ahead was dotted with huge white icebergs. But the three planes bravely roared their way out into the unknown and were soon lost to view in a cloudless sky.

I hurried down to St. John’s. I was very anxious about my friends. After a slow trip I put up at a little hotel. Just as I was signing the register I heard newsboys shrilly calling “Extra!” I ran out and seized a paper. In a glance I read the black headlines:

For hours I went through great distress worrying about Towers and Bellinger and their shipmates. Of course the story of the adventures of my shipmates is an old one now. Towers’ time of take-off had been 7.30 P.M. Until dark the other two planes followed him in column. Towers climbed above the clouds to take advantage of the moon. About 9.30 P.M. the NC-4, whose running lights had gone out, came dangerously close to the NC-3 without being seen. At this time the NC-4 began to speed up, Read deciding that his plane did not do so well at the slower speed.

The NC-1 and NC-3 kept in touch until dawn, when clouds hid them from one another. From that time on none of the planes sighted each other. Star shells from the destroyers were visible throughout the night. However, at times the visibility was so bad that the flyers could not see the tips of their wings. Passing through rain-squalls made the men sleepy. Towers used strychnine to offset this.

During the following morning Towers’ rougher calculation put the NC-3 near the Island of Flores. He was afraid to get too close lest he strike the high mountains in the fog that prevailed. As he had only about two hours of fuel left he decided to go down, attempt to locate his position exactly, and take off again for his goal.

Unfortunately the sea proved rougher than he thought. The NC-3 hit the top of a wave, porpoised to the top of another, and then slid down into the deep trough beyond until she struck a third heavy head-on blow that split the bow in several places, and she began to leak. Luckily the plane’s life was not ended then and there. As the radio ground wire had broken messages could not go out, though reports were received. A severe storm warning was the first news that came in.

The first thing the party did was to rig two canvas buckets out as a sea anchor. These were secured to the bow, and by dragging in the water kept the damaged craft head-on. After a bad night the storm broke with full fury on May 18th. The wind began to blow sixty miles an hour. The fusilage then began to leak so badly that it took the full energy of the crew to keep her bailed out. Towers being a good mariner, had oil put over the side but they drifted so rapidly it didn’t do much good.

At nine o’clock a heavy sea carried away the left wing pontoon. With this gone it looked as if the NC-3 could last but an hour or two longer. The men took turns strapping themselves out on the end of the opposite wing in order to keep the plane from capsizing.

The second night came on with hope for rescue very faint. The plane was leaking worse than ever and had drifted off her original course but they found that by manipulating the controls they could drift at an angle to the waves and wind. To add to their misery the radio operator intercepted a message that search was being made for them many miles to the westward. Toward morning they had hardly strength enough to’ bail. All were weak from exposure and lack of food, their sandwiches having in the beginning fallen into the bilge and become soaked with salt water.

Just as they reached the limit of their endurance land was sighted astern. It was the Island of San Miguel. Gradually they worked in close. Towers’ report reads:

“A destroyer came roaring out of the harbor, and when she got close I saw it was the Harding, Commander H. E. Cook commanding. We sent a signal by blinker light for her to merely stand by, as we intended making port without aid if possible.

“Just after this another wave took off our remaining wing pontoon and we very nearly capsized, but by this time we were off the entrance to the harbor, so we started the three serviceable engines, and with Moore on one wing, Richardson on the other, Lavender working signals, McCullough at the controls, and myself in the bow we came slowly into Ponta Delgada, amid a perfect bedlam of whistles, sirens, twenty-one gun salutes, waving of flags and wild dashing about of dozens of motor boats.”

The NC-1 had an almost identical experience up to nearly the end of her vicissitudes. I am sure that during this past summer most of the ill-fated planes that have been lost had the same experience upon landing. They hit the top of a high wave and porpoised to the top of another and then struck the oncoming wave with a bang, and of course being land planes they had no chance. Caught in fog, Bellinger decided to come down to avoid the mountains that might loom up at any moment. Like Towers he also found the sea rougher than he expected and banged his boat up badly. He, too, used a sea anchor. He nearly capsized several times. After six hours of misery he was picked up by the S. S. Ionia of the Hellenic Transport Company from Athens, Greece, and taken into Ponta Delgada.

The NC-4 with Read and five others aboard, made better speed than the other two and missed the worst of the fog though the next morning she ran into fog at 1200 feet and the pilot nearly lost control of her. After 13½ hours of flying her navigator sighted the southern tip of the island of Flores through a rift in the fog. She was flying at 3400 feet, but now spiralled down to 200 feet above the water hoping to pick up a destroyer and check her position.

At this moment the weather began to thicken and things looked bad. Then Read, with excellent judgment, decided to make Horta. Here he landed at 1.23 P.M. Greenwich time, May 18, 1919, after 15 hours 18 minutes of flying. He joined the others at Ponta Delgada on the 20th.

I recall that Lt. J. S. Breese, Engineer Officer of the NC-4, had put less gasoline in his plane than the others had and that I think was why the NC-4 was able to make better speed than the others.

At this point the Navy Department ruled that Read would go on alone, though it had been taken for granted that if Towers’ plane should be damaged, he, the commander, would board another plane. Read was weatherbound at Ponta Delgada until May 27th. He left for Lisbon at 8.01 A.M. Greenwich Civil time and arrived at the Portuguese city after 9 hours and 43 minutes in the air.

The Atlantic had been crossed by air for the first time in history.

Once more I turned south, sure my big chance had come and gone. But the American navy—bless her—had once more won the admiration of the world; and the Stars and Stripes had been the first across the Atlantic through the air.