I RETURNED to the States on the battleship Olympia which carried the remains of the Unknown Soldier. When I reached the Navy Department my position seemed to me to be untenable.

I was about to be demoted along with the rest of my class from Lt. Commander to Lieutenant (which ranks with Captain in the Army). The promotion we had gotten during the war was only temporary.

My class would soon get a permanent promotion but I would remain a Lieutenant, since a retired officer even if he has had as much active duty as his classmates cannot be promoted in peace time without an act of Congress, and that has been done only a few times in the history of our Navy.

On top of that I felt that I could continue with air expeditions with less handicap if I were not subject to military orders. So I wrote an official letter requesting that I be placed on inactive duty. Admiral Moffett did not approve it and the Personnel Bureau returned the letter to me without comment (as by law my request would have to be granted), stating that there was some more liaison work with Congress necessary and asked me to hold up my ‘request for retirement until that work was done.

Of course I withdrew my request for inactive duty and I went to the bat again on the Hill.

Everywhere I met with uniform courtesy. Those fellows up there in Congress are likeable and human and don’t deserve the mud that is slung at them. Many times I saw party lines break where the good of aviation and the navy was concerned.

During this last battle on Capitol Hill I had been urging the Bureau of Aeronautics to establish some aviation reserve stations throughout the country so we could keep on tap some of the fine aviators whom we had developed during the war and so that we could have an inflow of young blood.

“Bu there isn’t any money for such stations,” I was told again and again by the Chief.

“Build them without money,” said I on the spur of the moment one day soon after Congress had adjourned.

“All right, you do it,” came the prompt retort.

It was a challenge I could not resist, so I again delayed asking for inactive duty. Twenty-four hours later I had orders to establish a reserve air station at Squantum, Massachusetts, the function of which would be to train a certain number of carefully selected young men each year and keep in training the war aviators of New England.

I was given nothing but orders; no money, no men, no instructions. I think the Admiral had a quiet laugh to himself over my predicament when I left Washington.

In Boston I went to Rear Admiral Louis R. de Steiger, the Commandant of the New England Naval District and told him what I wanted to do. He felt the principle was sound and gave his enthusiastic backing, as did the Assistant Commandant Commander Fred Poteet. Next I got in touch will all the war aviators I could locate, who helped as I thought they would. They were enthusiastic beyond my highest expectations.

This was early spring. By summer we were able to put the station into commission, thanks to the reserves. It was a hand-to-mouth proposition in a good many ways. I borrowed working parties of sailors from battleship friends to build runways; lumber from the Navy Yard’s junk pile, and tools from whomever I could beg, borrow or steal. But when we were finished and had fixed up an old plane, we had an “honest-to-goodness” air station, preserving the skill of those who had learned to fly in the war, and the whole outfit had cost Uncle Sam almost nothing.

Well, that was convincing enough proof for the Navy Department. As a result I soon received orders to go to the Great Lakes Training Station at Chicago and erect another air station and organize the reserves in thirteen of the middle western states. I got the enthusiastic support of the Commandant Captain Evans and the Assistant Commandant Commander Jonas Ingram.

From this start there have grown up reserve stations at Rockaway, L. I., and Sand Point, Washington, besides the two mentioned above. After courses at these places students are sent for advanced work to the regular big stations at Hampton Roads, Va., and San Diego, Calif.

Then when Congress met again I went before the Naval Affairs Committee and asked for enough money properly to operate the stations, which was readily granted.

In the meantime, soon after New Year’s Day, 1924, just when I was finishing my job at the Great Lakes Station, I received telegraphic orders from Washington to report to the Navy Department in connection with a proposed flight of the dirigible Shenandoah, across the Arctic Ocean from Point Barrow, Alaska, to Spitzbergen. This route would take the big airship directly across the North Pole. My job was to assist Admiral Moffett in preparation for the expedition. A committee appointed by President Coolidge and composed of Captain Bob Bartlett, Peary’s old skipper, Commander Fitzhugh Green, who had been out on the Polar Sea and who is one of the greatest authorities in the country on the Arctic, Admiral Moffett, and Commander Furlong, had already gone into some details of the geographical and technical end of the flight.

The newspapers were full of the expedition. As Amundsen had not yet flown to the Pole it was considered that it might be a great feat for Americans to fly there first. But just as we had the party well under way the President, without explanation, called the whole project to a halt.

Once more I found myself in my usual position, out’ on. the end of a limb. There was not yet a proper plane for the transatlantic flight.

But the momentum I had gained in the way of Arctic interest, and the idea that ultimately America might first reach the Pole by air, stimulated me to continue on my own hook. I had never gotten out of my head my lifelong ambition to fly to the Pole.

Then came along the Navy and Congress and did that most gracious thing for me which I had always thought of as being so remote a possibility that I didn’t dare even hope for it.

They promoted me by special act of Congress to Lieutenant-Commander—not for any spectacular feat but on my general record. It was simply a recognition of the fact that I had plugged strenuously for the service I am so devoted to.

I could accomplish more as a Lieutenant-Commander than as a Lieutenant. I acted at once. My eyes were on the North Pole.

I joined forces with Captain Bartlett and at once began to plan a private Arctic air expedition. The fact that there still remained about I,000,000 square miles of unknown area north of the Arctic Circle seemed to justify a serious effort at arctic exploration by air.

I succeeded in securing the promise of $15,000 from Edsel Ford, and a like amount from John D. Rockefeller, Jr., while Captain Bartlett scraped up $10,000 from another source.

We found that Donald B. MacMillan had asked the Navy for a plane. His letter to the Navy Department said that he planned to do some flying around the south and western part of Greenland. As our idea was to use the northwestern comer, Etah, as a base and seek for land out in the Polar Sea I believed there would be no conflict of interests. Also I deemed it would be a sporting thing to do to tell the other man of my project, adding that we had asked for two amphibian planes and I didn’t see how he could get along with only one. I knew that only one suitable plane was available in the Navy but felt that we might get two of the amphibian planes from the Army.

At once MacMillan asked for two planes instead of one. But since there were only three available the Navy Department insisted that we join forces. MacMillan was to direct his expedition, with me commander of the naval unit which was to do the flying. He had the schooner Bowdoin, the naval unit was on the steamer Peary, which ship was under the command of Eugene McDonald, a business man and a very close friend of MacMillan’s. Our mission was to locate land supposed to exist in the Arctic Ocean in the Polar Sea northwest from Etah. The combined party organized under the auspices of the National Geographic Society of Washington, D. C.

I was allowed two pilots in addition to myself, Lt. Schur and Chief Warrant Officer Reber, very fine pilots, and had the pick of the whole Navy for mechanics. The mechanics who do all the gruelling work on the planes are generally forgotten or unnoticed, don’t let us forget them here. Their cheerful industry under the most trying conditions of wind, cold, rain and sleepless days and nights, made them all potential medal wearers.

It was in this group that I discovered Floyd Bennett who afterward flew to the North Pole with me. Up to the time of the Greenland expedition he had been an obscure aviation mechanic aboard a man-of-war, not even specially well known on his ship. Once he had his chance, he showed that he was a good pilot and one of the finest practical men in the Navy for handling an airplane’s temperamental mechanisms, and above that a real man, fearless and true—one in a million.

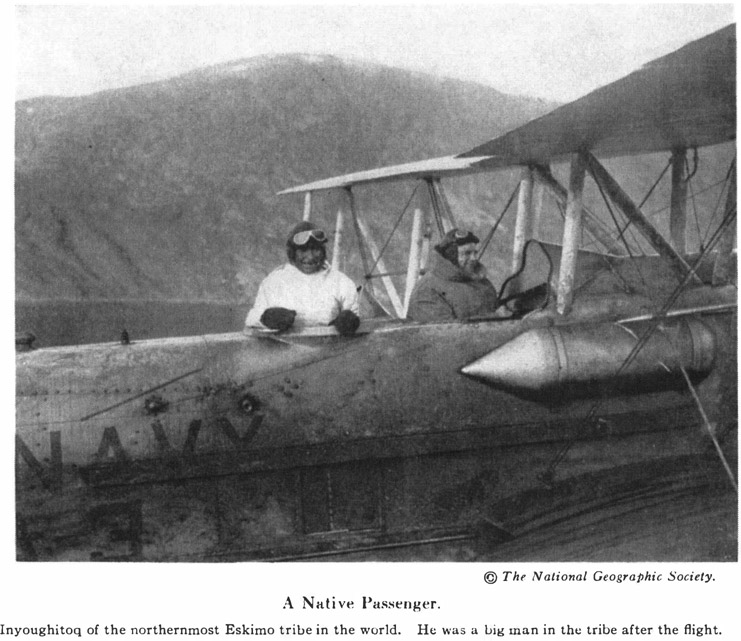

We left Wiscasset, Maine, on June 20, 1925. After an uneventful voyage of three thousand miles we reached on August 1st, Etah, North Greenland, the home of the northernmost Eskimo tribe in the world—a fascinating primitive people who live as they have for thousands of years because they dwell north of the ice that fills the dreaded Melville Bay and so are little touched by civilization. Ice and heavy weather had delayed us at times, but never seriously menaced our plans.

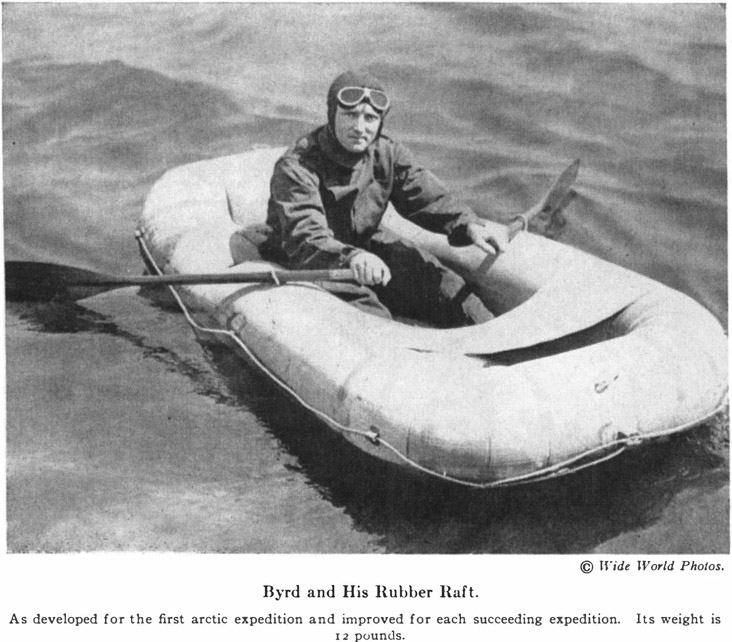

At 5.30 A.M., August 2, the morning after the Peary reached Etah, the eight officers and men comprising the Naval Aviation Unit started to work. With the enthusiastic assistance of the Eskimos and all hands, they built with our wing crates a runway for the planes on the ridiculously inadequate, very rocky beach—the best beach anywhere near Etah and one of the worst ones I had ever seen.

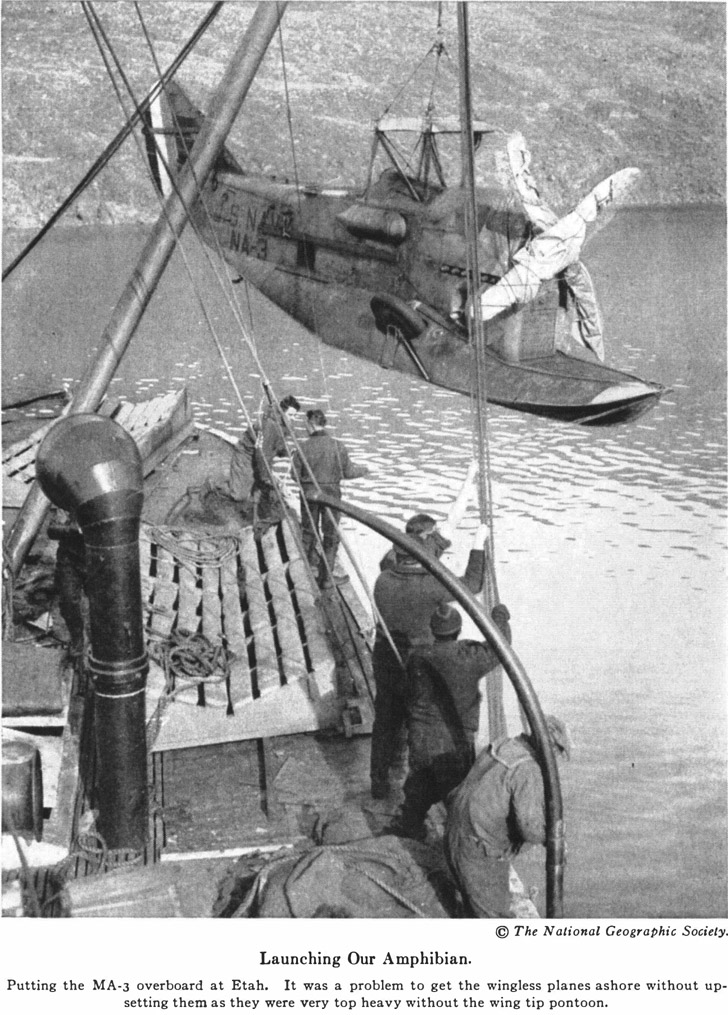

Working in the open on the delicate parts with bare hands, and at times exposed to snow squalls, my men got the wings and disassembled planes to the beach, erected them and we flew them by August 4. The rapidity with which these fellows did this is still a matter of wonder to me. When I gave the test flight to our machine the NA-1, I got a great satisfaction from the realization that aviation could function so far north at the very outpost of life. With any other planes than the Loening Amphibians, with their combination wheels and boats, I do not see how the flying ships could have been put in water and then dragged up on land.

As the beach proved entirely too small and rough, we moored the planes out to buoys which were dropped several hundred feet offshore. We thereafter operated entirely from the water.

We selected Etah to fly from because it is the nearest accessible harbor to the area in the Polar Seas we wanted to reach. For some reason the harbor is free enough of ice to be able with care to take off the plane without striking a hunk of it. Many harbors even hundreds of miles south of it we found to be filled with jagged cakes of ice.

Some of the gales which the planes had to ride out in the harbor were so severe that our anchors, which ordinarily would have held planes twice the size of our amphibians, dragged badly and it finally became necessary to keep the planes most of the time tied up astern of the Bowdoin and the Peary. Almost invariably our hours of sleep were interrupted by the deck watch with a report that one of the buoyed planes was dragging anchor, that the wings of another were about to strike the ship’s side, or that a miniature iceberg was bearing down upon a third.

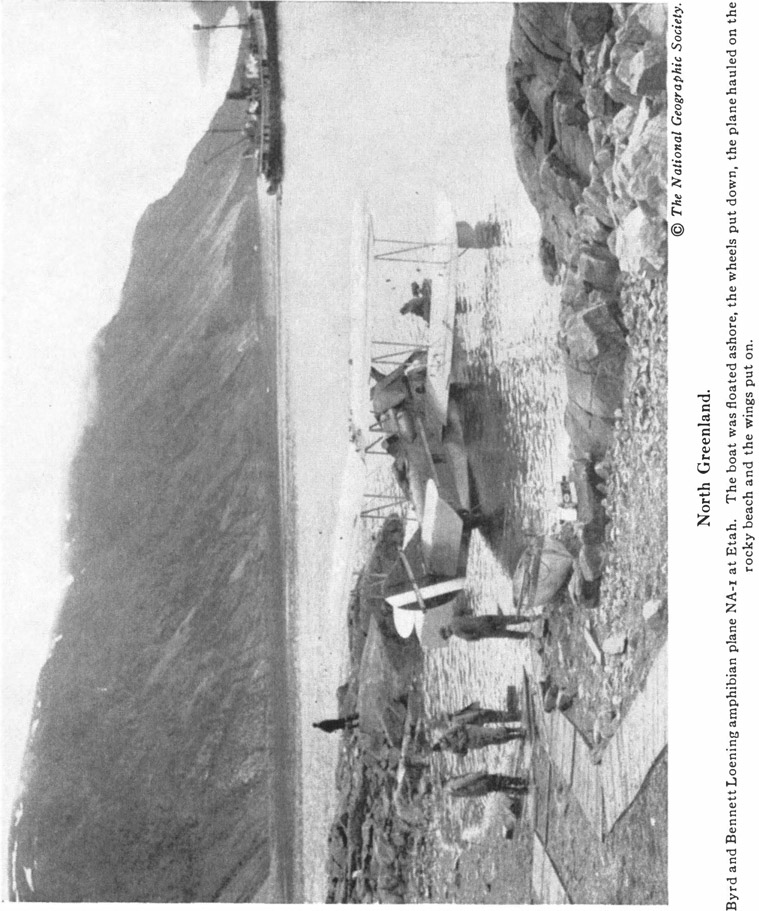

On August 4 we took our ten specially picked carrier pigeons ashore in the pigeon house, to get them oriented to the locality. On the 10th we turned them loose, but only four of them returned. Chief Aerographer Francis, who acted as Navy photographer, meteorologist and pigeon man, reported to me that they had been killed by Arctic falcons. It would seem, then, that pigeons are not practicable for communication purposes in that part of the Arctic. We had thought that they might be used for communicating with Etah in case of a crash, if our radio were put out of commission.

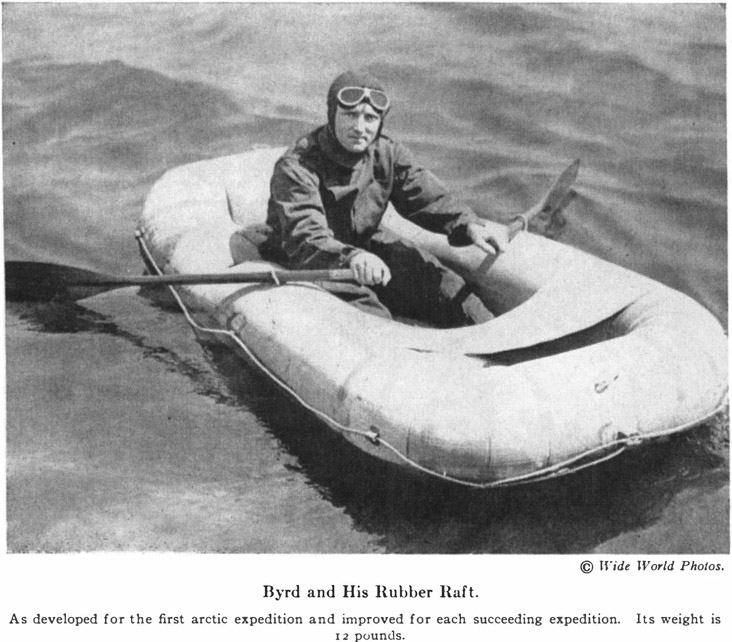

We spent August 5 making radio and full-load tests. As we found that, with the load of food, rifles, ammunition, boat, etc., stowed in the tail, the plane was thrown out of balance, we spent the 6th talking a 33-gallon emergency gasoline tank out of the bow to make room for stowing the gear. At 7.00 P.M. August 6, fog descended, visibility became very poor, and it began to rain. The downpour continued for 24 hours, after which a southwest gale sprang up. This blow turned into a snowstorm the following day at 2.00 P.M.

From general conditions and information supplied by the Eskimos, it was realized from the first that we were having scarcely any summer at all, so the Naval unit put forth its greatest effort in accomplishing its work in the shortest possible time. In fact, it turned out that after the planes were ready for flight there were but fifteen days of “summer” in which to accomplish our mission.

It is an astonishing fact that of those fifteen days only three and three-quarters were good for flying; two were fair flying days and one indifferent. More than half the time was either dangerous or very dangerous for flying. Yet due to the great work of the mechanics the three planes flew more than 5000 miles counting all flights without any forced landing. While in the air we saw 30,000 square miles, some of which, being inaccessible to foot travelers, had never before been seen by human eye.

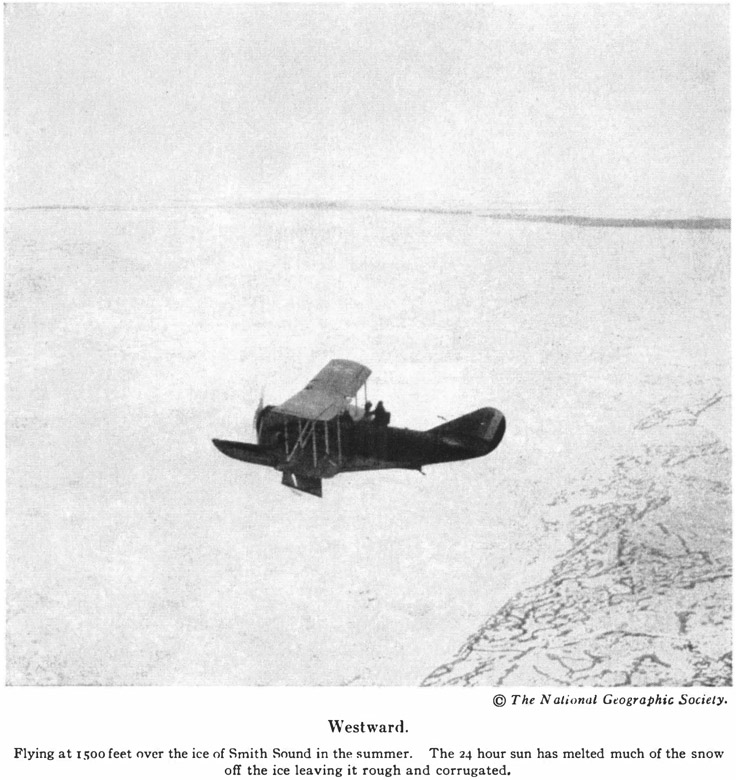

Our first reconnaissance flight was to Cape Sabine, which lay on our proposed course toward the Polar Sea, 30 miles from Etah. We found that the ice began several miles north of Etah, and covered all the water to the northward as far as we could see. We flew low, hoping to find the ice smooth enough to land on but it was rough and corrugated, and generally in such condition that landing upon it would have been as disastrous as landing among large rocks—a plane would have been completely demolished and, of course, the flyers probably would not have been able to walk away from the wreck.

We realized that the ice-landing skis which we had brought to use in place of wheels would be of no use to us under such conditions. There were pools of water on the ice and here and there open leads filled, more or less, with detached pieces of ice. It was easy to see why Ellesmere Island is inaccessible in the summer to the dog-sledge travelers.

In all the hundreds of square miles of ice over which we flew later on, both land and sea, we did not see a single place on the ice where a landing could be made without disaster!

As the engine on the NA-1 developed a knock on the 5th we decided to put in a new motor. We felt that we must do everything humanly possible to prevent a forced landing on the ice. So my mechanics set about shifting a 900-pound motor with our jerky ship’s boom, while the plane bobbed up and down in the water alongside the ship. Though I watched the men work, it is still a mystery to me how they did it.

Bennett and Sorensen, also a perfect shipmate, worked all day and all night connecting up the intricate mechanism of the motor, out in the cold and the wet, and reported the plane ready on the morning of the 7th. The work had been accomplished in about one-fourth the time I expected it to take. When the motor started and hit on all twelve cylinders it was a very pleasant surprise. Then Bennett and Sorensen reported themselves ready to fly! Rest seemed to mean nothing to them. But as the weather was nasty I made them turn in.

That is the kind of spirit all but one of the men with me displayed. No handicaps—and there were plenty—were too great for them to overcome. It is a pleasure to record the great courage, indomitable spirit, and unusual ability of those fellows.

At 4.00 A.M. on the 8th, during a gale, the NA-3, which was tied up to an anchored buoy, barely missed destruction from a drifting iceberg. As later she began to drag anchor we finally had to tie her up astern of the Bowdoin. The bad weather persisted until 7.00 P.M. when it abated. I immediately gave orders to prepare for our first long flight into Elles-mere Island to attempt to put down an advance base, as the distance we should have to go was such that we should have to advance by bases.

We left Etah Harbor at 9.10 P.M. with Schur, pilot, and Rocheville, mechanic, and MacMillan passenger, in the NA-2; and Reber, pilot, and myself, relief pilot and navigator, in the NA-3. Just before we took off, a herd of a dozen walrus came up a few feet from our plane. They apparently became enraged at it and dived toward us, but we gave the motor the gun and could not see them when they rose to the surface again because of the spray kicked up by the propeller.

As the midnight sun did not set for some days yet we had normal daylight for 24 hours.

We set a course for Cannon Fiord, which lies on a line from Etah through Cape Thomas Hubbard on the Polar Sea, from which Peary in I 906 thought he saw the high peaks of a great land to the northwest.

At last we were to find out whether or not we could navigate a plane where the north magnetic pole is on one side, off to the southward, and the North Pole is on the other side, and where the force of the earth’s magnetism acting on the compass needle is very weak. I noted immediately that the steering compass did not move at all, but pointed east all the time. Fortunately we had provided a more sensitive instrument which we called the navigator’s compass. It began to oscillate slowly at first; but after we had steered a steady course for a while it finally settled down.

In clear weather the sun compass enabled us to do accurate navigation. I was delighted with it. Mr. Albert H. Bumstead, of the National Geographic Society, devised it for our trip and I consider it a great contribution to science.

When we reached Cape Sabine we took a bearing on two points 30 miles apart, the direction of which Peary had established, and found that in addition to the I 03 degrees of error caused by our being north of the magnetic pole, there was an additional and unexpected error of 30 degrees, an unheard-of deviation. (Deviation is that error caused by local disturbance, such as metal in the plane.)

When we wanted to fly north by compass the compass needle pointed nearer south than north. A curious sensation indeed!

As we flew over Smith Sound, we could see to the north at a glance the ice-packed area Peary and Bartlett had such a difficult time getting through with the Roosevelt in 1908. The thought occurred to me: How we could have helped Peary by indicating to him the direction of the very few open leads of water so easily visible to us, but so difficult to locate even from the crow’s nest of a ship! I was impressed, too, with the fact that we were traversing in a few minutes areas that it had taken him days to cross. In fact we crossed in thirty minutes a stretch that took Hayes thirty days about fifty years ago.

We reached Cape Sabine at 940 P.M., and passed directly over the spot where 18 of General Greely’s men died from cold and hunger. I have never seen a bleaker spot. Over to the northward we could make out Bache Peninsula, which Peary traversed in 1898 and where his hunters killed musk oxen for a fresh meat supply.

Beyond Cape Sabine, the view that opened was superb. We were stirred with the spirit of great adventure—with the feeling that we were getting a comprehensive idea, never before possible, of the Arctic’s ruggedness and ruthlessness.

I believe that we have a new story to tell of the grandeur of Ellesmere Island. It was evident that the greater part of the land we saw had been inaccessible to the foot traveler, who, keeping largely to the water routes, with the view cut off by the fiords’ great perpendicular cliffs, could not have realized the colossal and multifold character of the glacier-cut mountains.

But there was no time to enjoy the view. Since any slight engine trouble might require a landing, I naturally looked about for some suitable place in which to put a plane down if necessary. With our load the landing would have to be made flying at 50 or 60 miles an hour.

I searched carefully and did not see a single place on the land or on the water where a landing would not have meant disaster. The land was everywhere too irregular and the water was too filled with ice either broken up into drifting pieces or in large, unbroken areas. At that moment I realized we were confronted with an even more difficult and hazardous undertaking than we had anticipated. I knew, too, that no matter what judgment we exercised we should have to have a little luck to comply with Secretary Wilbur’s last admonition to me to bring the personnel back safely.

We had confidently believed that the fiords would be free of ice. That they were not was due probably to the fact that we were having scarcely any summer. We could not use the sun compass because the sun was obscured. So we continued steering east by the magnetic compass. By sighting astern on known points I was delighted to find that we were almost exactly on our course. A little later, however, the wind-drift meter indicated a strong wind from the north and we had to change course about 10 degrees to allow for it.

No idea of the extremely irregular and rugged character of Ellesmere Island can be gathered from the maps and charts. In fact many of the mountains we saw were uncharted. The higher mountains were largely snow-covered and their glaciers extended down to the sea.

We continued on to Knud Peninsula (the tongue of land lying between Hayes and Flagler Fiords), flying at an altitude of 4,000 feet. Low-lying clouds hung over the peninsula, with many rugged peaks appearing above them.

Ahead we saw very high snow and cloud-covered mountains which appeared to be impassable. We kept on, hoping to find some way through. However, we soon realized that the clouds were so high that no aircraft loaded as ours was could possibly get over them. The weather astern had begun to thicken and the clouds covered most of the landmarks.

Weather conditions change very rapidly in the Arctic, a fact which is of great concern to the aviator who cannot fly through fog and clouds over the land as he can over the sea. There is too great danger of running into a mountain or cliff. Neither can he land and wait for the weather to clear, if he has no landing place. Nor can he keep on flying around for the good reason that his gas eventually gives out.

We decided to tum back, fly over the clouds and take a chance on finding Etah. Without a landmark it was necessary to steer a compass course. Luckily, we found a rift in the clouds over Smith Sound, with fog only in places here and there on the water. After a hazardous trip we were finally able to make the ships’ base, although a 30-mile wind from the north made rough landing.

Upon our return, Aerographer Francis handed me a report that a gale of great intensity was rushing toward Etah from the south. All flying equipment was, therefore, “secured.” A driving snowstorm soon set in, bearing out Francis’ prediction. The next morning at 3 o’clock a piece of iceberg weighing perhaps 500 tons was driven by the gale between the Peary and the planes, barely missing the latter, and giving us some anxious moments.

A few hours later I called the Naval unit together and told them that I would never again order any of them to fly over Ellesmere Island. It was too risky a business. Engines were not so reliable as now. Yet when the time came my men were ready and eager to volunteer for any flying that was to be done.

That afternoon it was decided that we should try to get beyond the high, snow-covered mountains by going through a gap to the south of our course, even though this was a roundabout way to reach our proposed Polar Sea base on Axel Heiberg Island.

When the gale subsided at 5.30 P. M. we made a reconnaissance and radio test flight to Cape Sabine. We ran into snow over the Cape and found Elles-mere Island completely smothered by fog and snow.

The weather cleared toward Ellesmere Island the next morning, August 11, so all three planes prepared to leave immediately for Bay Fiord to attempt to put down a base of fuel, food and ammunition on its shore.

We got away at 10.40 A.M. in all three planes. Schur piloted the NA-2, Reber the NA-3 and Bennett and I the NA-1. Our mission was to locate a landing place suitable for a base between Etah and the Polar Sea, a non-stop flight would be too far to go with the cruising radius of our planes. Also, we felt a base to be absolutely necessary because food and fuel had to be deposited on the shore of the Polar Sea before we should dare to make a flight over it. Otherwise we faced starvation in case we had to walk back.

At 11.15 A.M. we passed over the north end of Cape Sabine. We reached the eastern end of Flagler Fiord at 11.45, flying at an altitude of 4,000 to 7,000 feet. At the latter altitude temperature was several degrees below zero, which felt bitterly cold in the sharp wind.

Hundreds of mountain peaks, dazzling white with snow, ranged along our northern horizon. As clouds rested on their summits we could not see beyond in the direction of Greely Fiord. Below us was a chaotic landscape of glacier, fiord and showy highlands, the latter cut by sharp black ravines.

At 12.45 we were across the land, reaching the eastern end of Bay Fiord. The crossing of the glacier had taken us a few minutes. This was a curious contrast to the crossing Fitzhugh Green made in 1914 when he struggled up over the steep ice slopes and crevasses for days in temperatures down to 60 degrees below zero. Surely the plane has altered polar work.

Here the clouds increased and visibility northward was ruined by a heavy mist that hung over Eureka Sound. Below us the fiord was covered with ice. Soon the NA-2 disappeared entirely in the clouds. As the NA-3 was having trouble getting altitude she turned back toward Etah. I took the NA-1 on down toward Eureka Sound and finally found one suitable landing place on the north shore of Bay Fiord. But this spot was only a temporary opening where the wind had blown the drifting ice to one side.

I was greatly worried about the other planes. I had had an extremely difficult time keeping track of them against the dazzling snow background. A forced landing would have been bad indeed. It was important that if one came down we should know where to search for her, but we could find no trace of them. My joy was unbounded when we got back to base and found them safely anchored in the harbor. The NA-2 and NA-3 having arrived at 2.30 P.M. and we about an hour and a half later. We were pretty well chilled when we clambered stiffly out of our seats.

On account of the good weather I decided I must waste no time. On our return that afternoon I noted that Beistadt Fiord was comparatively free of ice and clouds. This meant I could leave a cache in it, even though it was slightly south of the line we hoped ultimately to travel towards the Polar Sea.

Though tired from the day’s flight, my men did not demur at preparing at once for another. We hopped off at 9.30 P.M. with all three planes and the same pilots. But when we reached Beistadt Fiord a heavy crosswind prevented us from landing. Probably its high cliffs, 2,000 vertical feet I judge, create a suction from the glacier above just as New York skyscrapers do.

We turned back and recrossed the inland ice-cap. At the western end of Hayes Sound we found enough open water for a landing. We came down and taxied toward shore. But the high wind made it impossible for us to reach the beach without wrecking the plane. So cold and wet from the spray of the high sea we took off again and reached the ship about midnight. On the way we saw still another spot where a landing would be possible; the inner end of Flagler Fiord.

At last we had been able to land in the interior of Ellesmere Island, but the water had been dangerously rough. We noted on this occasion a very interesting thing. The wind rushed down the glacier, but changed its direction several miles from its foot. We afterward found that no matter what the direction of the wind elsewhere it generally flowed down the glacier and then subsided or changed its direction some miles beyond the foot.

Another interesting phenomenon experienced in the Far North was the difficulty of judging distances—something at which the aviator must be expert. This difficulty was occasioned by the great size of the cliffs, and the clearness of the atmosphere—when it is not misty. When we landed in Hayes Fiord we thought we were landing a few hundred feet from the ice fringe on the shore line at the foot of the 2,000-foot cliffs, whereas to our great surprise we found ourselves more than a half mile away.

Now came a period of very cold winds. After being buffeted by a gale on the morning of the 13th, the NA-2 began to sink. When the engine was half covered with water, the members of the expedition, by prompt and heroic effort, saved the plane. We later hoisted it on the deck of the Peary to change the water-soaked motor; but it was never able to fly again.

Having seen open water at the mouth of Flagler Fiord, we decided to attempt to put down a base there. At 11.45 on the morning of the 14th of August the NA-3 and NA-1 left Etah for this spot. After an hour and a half we came down at our destination and got the planes to within 50 feet of the shore. We waded in the icy water to the beach, carrying 200 pounds of food and 100 gallons of gas. In addition we left 5 gallons of oil, primus stove, camping outfit, smoke bombs, rifle and ammunition, and matches. An iceberg drifted into our plane and we had a great tussle keeping it from being smashed. We were much relieved when we got the NA-1 off for Etah.

In order to take advantage of the fair weather that had blessed us momentarily we again took off at about 5 A.M. the following morning. Surely it was a strenuous campaign. When we reached Flagler Fiord we found that during the few hours we had been away the ice had closed in and completely covered our landing place. We then cruised about for some 60 miles attempting to locate a landing place in one of the other fiords, but were unsuccessful.

About a half hour before midnight there was the effect of twilight among the fiords. I wondered if any human being had ever before witnessed such a weird, mysterious, desolate scene. There was a sense of great loneliness and the plane seemed very small indeed. Once when we flew down into one of the black chasms in the dimness we lost track of Nold alone in the NA-3. He evidently had missed us also for finally we located him, just a speck in the distance and apparently headed for the North Pole! We gave our motor all the power she had and after a good race overhauled him. What Nold’s compass was doing, or what he was about, I never have found out. Nold told me he had felt very lonely indeed when he got lost.

I had on polar bear trousers, Eskimo boots lined with sheepskin, and a reindeer-skin jacket—the warmest clothes known—but while leaning out of the cockpit to navigate I got very cold.

The next day we started out again. For a week Bennett had had very few hours’ rest, but he insisted on going with me. He did most of the flying while I navigated and flew from time to time when I was sure of our location, and could let the navigating go for a while.

We now headed into the northwest. The season was getting late and I wanted a look at the regions above the well-traveled route down Hayes and Flagler inlets. At midnight fog came on and we were forced to land in Sawyer Bay a magnificent place with its high canon like cliffs. We ate a midnight lunch of pemmican and tea and lay down in our skin clothes to rest to wait for the clouds to clear ahead.

Finally on taking off the NA-3 developed such a knock that Schur preferred not to try a flight over the mountains to the north. About 5 A. M. Bennett and I in the NA-1 crossed the high snow covered peaks and got a look beyond.

There followed for Bennett and me one of the greatest battles of our lives. We looked down on an unexplored part of Grinnell Land into areas cut jagged by ages of ice into pinnacles and precipitous cliffs. The view was awful in its magnificence, and the air was the roughest I had ever experienced. We were tossed about like a leaf in a storm and often it looked as if we would certainly be dashed down on the irregular ice of the glaciers beneath us. Bennett showed there the stuff he is made of. Ahead of us were higher snow covered mountain peaks that disappeared into the clouds. We made a desperate effort to get through but there was no opening in the clouds. Most reluctantly we turned back fighting every inch of the way.

We returned to Sawyer Bay and joined the NA-3. We left a cache of gasoline, oil and food and hopped off for Etah at 7.05 A.M., when we rejoined the ship at Etah a gale was blowing.

On the 17th the gale finally subsided. At 8 P.M. some gasoline on the water around the Peary caught fire and for a few moments it looked as if the NA-3, which was tied up astern, and the whole ship would go. Sorensen used splendid head work in casting the NA-3 adrift immediately and some one procured a fire extinguisher and threw it to Nold, who was on the flaming plane.

My diary for the 17th has the following entry:

“The saving of the NA-3 from destruction by fire today was just another example of the fine spirit of the personnel the Navy has assigned to me for this duty. Whether we succeed or fail, they deserve the highest success. They have overcome almost insuperable odds that the elements and poor facilities have brought about. They have been indefatigable and courageous, and whenever there has been a job to do they have needed no commanding officer to tell them to do it, to spur them to greater effort.

“What they have accomplished on this trip has been almost superhuman, and even if we succeed in the highest measure it cannot increase my pride in them. Their attitude seems to have been to live up to the best traditions of the Navy. They never hesitated to spend hours flying over areas where their lives depended entirely on the reliability of the engines.”

There was one forced landing during our Arctic work, but it did not come until we were ready to leave Etah, where there was open water.

By the 20th the burned wings on the NA-3 had been replaced by new wings, and a new engine installed. But due to Bennett the NC-1 seemed to be in better shape than any of the other planes so he and I loaded up to use our sub-base and fly to the limit of our cruising radius or bust. We were ready to go again. But MacMillan gave us orders not to go and we couldn’t change him. That night the head of Etah Fiord froze over. This meant, MacMillan declared, that a forced landing in Cannon Fiord or Eureka Sound would certainly result in a freezing-in of at least one of the ships that could not desert us.

Bennett and I were greatly depressed that we could not go on with our work, for we were learning the location of the few water landing places and we never gave up the hope of discovering an island in the Arctic.

However, there was another great adventure ahead of us—the flight over the Greenland ice-cap. We spent several days making photographic flights, and on the 22nd the NA-I and NA-3 left Etah for Igloodahouny, 50 miles south of us. Reber piloted the NA-3, with Gayer as photographer and Nold as mechanic; Bennett, Francis and I were in the NA-1.

Half a mile from Etah the engine of the NA-3 threw her connecting rod and stopped dead. Reber was forced to land and had to be towed back. The NA-3 was then put on the Peary alongside the NA-2. I was sorry to see Reber have that hard luck, for, due to serious illness, he had been able to make only two flights over Ellesmere Island.

After landing to see that the NA-3 had gotten down without injury, we continued in the NA-1 to Igloodahouny, an Eskimo village south of Etah, where we found a fine beach. We landed and made camp.

At 3.15 I took the NA-I for a flight over the Greenland ice-cap. The visibility was wonderful. We climbed to an altitude of 1,000 feet and could see 100 miles in every direction. As we got farther in over the ice-cap it grew very cold, although at 7,000 feet we encountered a warmer stratum of air.

We were flying in a direction a little south of east over a part of the ice-cap never before explored. Soon we saw in the direction we were going that the ice reached an altitude which appeared to be equal to that of the plane—over feet.

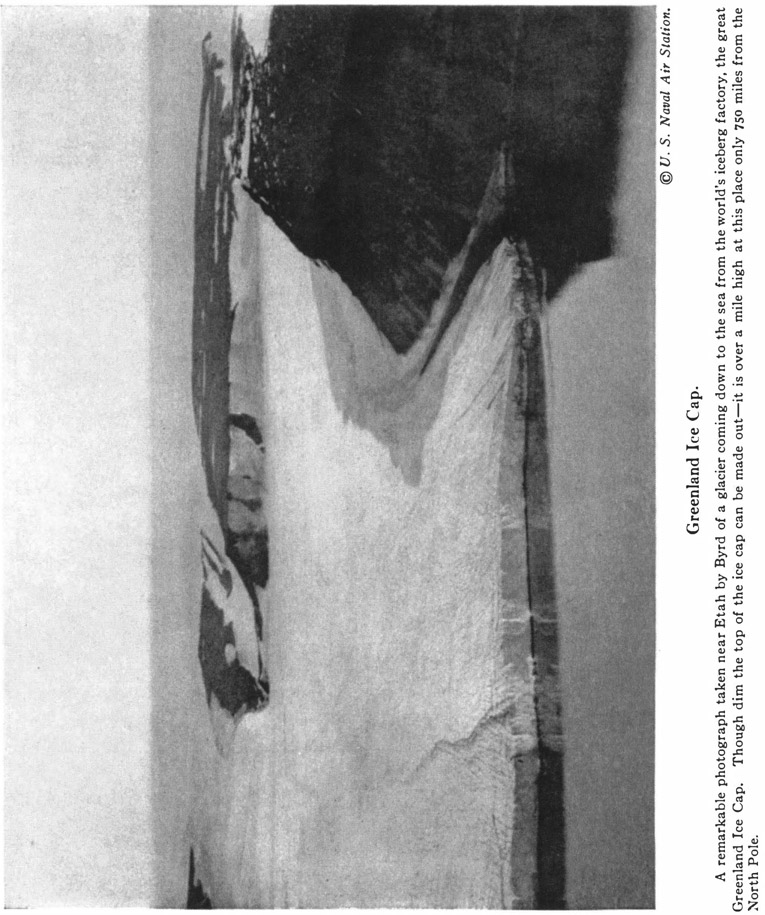

I especially enjoyed this flight. The Greenland ice-cap is one of the great natural wonders of the world—1,500 miles long, about 500 miles wide, with an area of 700,000 square miles of solid ice and averaging over a mile in height—the world’s great iceberg factory. The glaciers near the foot are greatly crevassed, but farther up, where they join the ice-cap, they are fairly smooth and firm. The shape of the ice-cap seems to be that of the crystal of a watch, so that it would be difficult to land an airplane near its edge without dashing into a crevasse; but 50 to miles inland, though a bit rolling, there seem to be fiat places where a plane with skis could land.

We returned to Igloodahouny almost literally frozen stiff. But we were proud of the NA-1, for thanks to Bennett she had flown more than 2,500 miles in the Arctic in every kind of weather, and she appeared to be in just as good condition as when we started.

I was stirred with the conclusion that aviation could conquer the Arctic. Contrary to the expectation of the world we were returning without disaster.

We had a cold and stormy passage back to New York, but reached there safely about October 1. Once more I had been close to something very big. However, I came back with secret confidence that I was perhaps very close to the biggest thing in my life. With Bennett I quietly talked over the possibility of reaching the North Pole by air. Our Greenland experience convinced me this feat was possible.

So as had often happened before I tried to use hard knocks as a step for the next sortie against fate and the beckoning future.