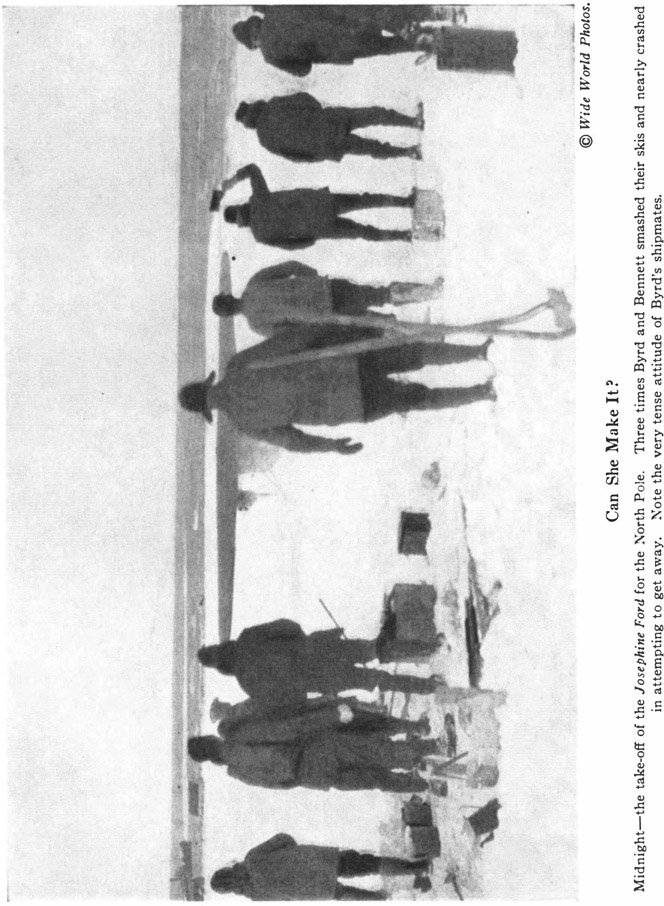

WITH a total load of nearly 10,000 pounds we raced down the runway. The rough snow ahead loomed dangerously near but we never reached it. We were off for our great adventure!

Beneath us were our shipmates—every one anxious to go along, but unselfishly wild with delight that we were at last off—running in our wake, waving their arms, and throwing their hats in the air. As long as I live I can never forget that sight, or those splendid fellows. They had given us our great chance.

For months previous to this hour, utmost attention had been paid to every detail that would assure our margin of safety in case of accident, and to the perfection of our scientific results in the case of success.

We had a short-wave radio set operated by a hand dynamo, should we be forced down on the ice. A handmade sledge presented to us by Amundsen was stowed in the fuselage, on which to carry our food and clothing should we be compelled to walk to Greenland. We had food for ten weeks. Our main staple, pemmican, consisting of chopped-up dried meat, fat, sugar and raisins, was supplemented by chocolate, pilot-bread, tea, malted milk, powdered chocolate, butter, sugar and cream cheese, all of which form a highly concentrated diet.

Other articles of equipment were a rubber boat for crossing open leads if forced down, reindeer-skin, polar-bear and seal fur clothes, boots and gloves, primus stove, rifle, pistol, shotgun and ammunition; tent, knives, ax, medical kit and smoke bombs—all as compact as humanly possible.

If we should come down on the ice the reason it would take us so long to get back, if we got back at all, was that we could not return Spitzbergen way on account of the strong tides. We would have to march Etah way and would have to kill enough seal, polar-bear and musk-ox to last through the Arctic nights.

The first stage of our navigation was the simple one of dead reckoning, or following the well-known landmarks in the vicinity of Kings Bay, which we had just left. We climbed to 2,000 feet to get a good view of the coast and the magnificent snow-covered mountains inland. Within an hour of taking the air we passed the rugged and glacier-laden land and crossed the edge of the polar ice pack. It was much nearer to the land than we had expected. Over to the east was a point where the ice field was very near the land.

We looked ahead at the sea ice gleaming in the rays of the midnight sun—a fascinating scene whose lure had drawn famous men into its clutches, never to return. It was with a feeling of exhilaration that we felt that for the first time in history two mites of men could gaze upon its charms, and discover its secrets, out of reach of those sharp claws.

Perhaps! There was still that “perhaps,” for if we should have a forced landing disaster might easily follow.

It was only natural for Bennett and me to wonder whether or not we would ever get back to this small island we were leaving for all the airmen explorers who had preceded us in attempts to reach the Pole by aviation had met with disaster or near disaster.

Though it was important to hit the Pole from the standpoint of achievement, it was more important to do so from that of our lives, so that we could get back to Spitzbergen, a target none too big. We could not fly back to land from an unknown position. We must put every possible second of time and our best concentration on the job of navigating and of flying a straight course—our very lives depended on it.

As there are no landmarks on the ice, Polar Sea navigation by aircraft is similar to that on the ocean, where there is nothing but sun and stars and moon from which to determine one’s position. The altitude above the sea horizon of one of these celestial bodies is taken with the sextant. Then, by mathematical calculations, requiring an hour or so to work out, the ship is located somewhere on an imaginary line. The Polar Sea horizon, however, cannot always be depended upon, due to roughness of the ice. Therefore we had a specially designed instrument that would enable us to take the altitude without the horizon. I used the same instrument that we had developed for the 1919 trans-Atlantic flight.

Again, should the navigator of a fast airplane take an hour to get his line of position, by the time he plotted it on his chart he would be a hundred miles or so away from the point at which he took the sight. He must therefore have quick means of making his astronomical calculations.

We were familiar with one means of calculation which takes advantage of some interesting astronomical conditions existing at the North Pole. It is a graphical method that does away largely with mathematical calculations, so that the entire operation of taking the altitude of the sun and laying down the line of position could be done in a very few minutes.

This method was taught me by G. W. Littlebales of the Navy Hydrographic Office and was first discovered by Arthur Hinks of the Royal Geographic Society.

So much for the locating of position in the Polar Sea by astronomy, which must be done by the navigator to check up and correct the course steered by the pilot.. The compass is generally off the true course a greater or less degree, on account of faulty steering, currents, wind, etc.

Our chief concern was to steer as nearly due north as possible. This could not be done with the ordinarily dependable magnetic compass, which points only in the general direction of the North Magnetic Pole, lying on Boothia Peninsula, Canada, more than a thousand miles south of the North Geographical Pole.

If the compass pointed exactly toward the Magnetic Pole the magnetic bearing of the North Geographical Pole could be calculated mathematically for any place on the Polar Sea. But as there is generally some local condition’ affecting the needle, the variation of the compass from true north can be found only by actual trial.

Since this trial could not have been made over unknown regions, the true directions the compass needle would point along our route were not known. Also, since the directive force of the earth’s magnetism is small in the Far North, there is a tendency of the needle toward sluggishness in indicating a change in direction of the plane, and toward undue swinging after it has once started to move.

Nor would the famous gyroscopic compass work up there, as when nearing the Pole its axis would have a tendency to point straight up in the air.

There was only one thing to do—to depend upon the sun. For this we used a sun-compass. The same type instrument that had been invented and constructed for our 1925 expedition by Albert H. Bumstead, chief cartographer of the National Geographic Society. I do not hesitate to say that without it we could not have reached the Pole; it is even doubtful if we could have hit Spitzbergen on our return flight.

Of course, the sun was necessary for the use of this compass. Its principle is a kind of a reversal of that of the sundial. In the latter, the direction of north is known and the shadow of the sun gives the time of day. With the sun-compass, the time of day is known, and the shadow of the sun, when it bisects the hand of the 24-hour clock, indicates the direction after the instrument has been set.

Then there was the influence of the wind that had to be allowed for. An airplane, in effect, is a part of the wind, just as a ship in a current floats with the speed of the current. If, for example, a thirty-mile-an-hour wind is blowing at right angles to the course, the plane will be taken 30 miles an hour to one side of its course. This is called “drift” and can be compensated for by an instrument called the drift-indicator, which we had also developed for the first trans-Atlantic flight.

We used the drift-indicator through the trapdoor in the plane, and had so arranged the cabin that there was plenty of room for navigating. There was also a fair-sized chartboard.

As exact Greenwich time was necessary, we carried two chronometers that I had kept in my room for weeks. I knew their error to within a second. There seems to be a tendency for chronometers to slow up when exposed to the cold. With this in mind we had taken their cold-weather error.

As we sped along over the white field below I spent the busiest and most concentrated moments of my life. Though we had confidence in our instruments and methods, we were trying them for the first time over the Polar Sea. First, we obtained north and south bearings on a mountain range on Spitzbergen which we could see for a long distance out over the ice. These checked fairly well with the sun-compass. But I had absolute confidence in the sun-compass.

We could see mountains astern gleaming in the sun at least a hundred miles behind us. That was our last link with civilization. The unknown lay ahead.

Bennett and I took turns piloting. At first Bennett was steering, and for some unaccountable reason the plane veered from the course time and time again, to the right. He could glance back where I was working, through a door leading to the two pilots’ seats. Every minute or two he would look at me, to be checked if necessary, on the course by the sun-compass. If he happened to be off the course I would wave him to the right or left until he got on it again. Once every three minutes while I was navigating I checked the wind drift and ground speed, so that in case of a change in wind I could detect it immediately and allow for it.

We had three sets of gloves which I constantly changed to fit the job in hand, and sometimes removed entirely for short periods to write or figure on the chart. I froze my face and one of my hands in taking sights with the instruments from the trapdoors. But I noticed these frostbites at once and was more careful thereafter in the future. Ordinarily a frostbite need not be dangerous if detected in time and if the blood is rubbed back immediately into the affected parts. We also carried leather helmets that would cover the whole face when necessary to use them.

We carried two sun-compasses. One was fixed to a trapdoor in the top of the navigator’s cabin; the other was movable, so that when the great wing obscured the sun from the compass on the trapdoor, the second could be used inside the cabin, through the open windows.

Every now and then I took sextant sights of the sun to see where the lines of position would cross our line of flight. I was very thankful at those moments that the Navy requires such thorough navigation training, and that I had made air navigation my hobby.

Finally, when I felt certain we were on our course, I turned my’ attention to the great ice pack, which I had wondered about ever since I was a youngster at school. We were flying at about 2,000 feet, and I could see at least 50 miles in every direction. There was no sign of land. If there had been any within 100 miles’ radius we would have seen its mountain peaks, so good was the visibility.

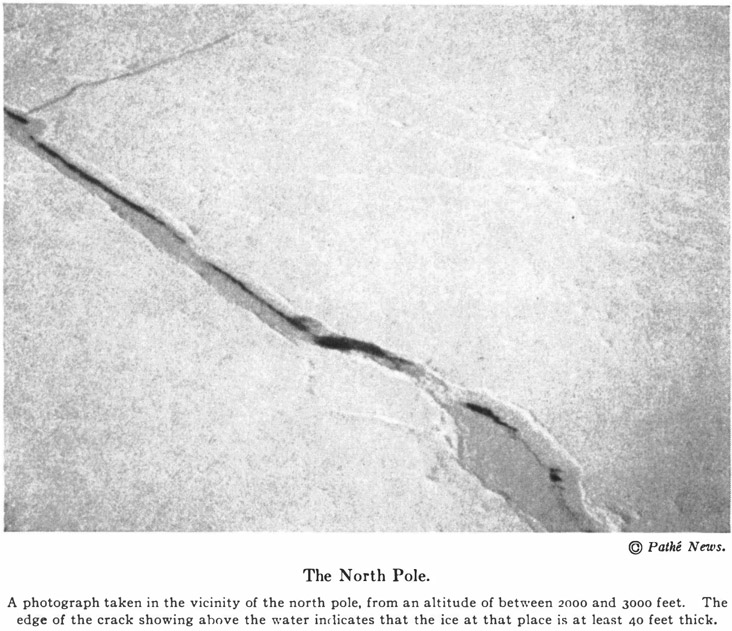

The ice pack beneath was criss-crossed with pressure ridges, but here and there were stretches that appeared long and smooth enough to land on. However, from 2,000 feet pack ice is extraordinarily deceptive.

The pressure ridges that looked so insignificant from the plane varied from a few feet to 50 or 60 feet in height, while the average thickness of the ice was about 40 feet. A flash of sympathy came over me for the brave men who had in years past struggled northward over that cruel mass.

We passed leads of water recently opened by the movement of the ice, and so dangerous to the foot traveler, who never knows when the ice will open up beneath and swallow him into the black depths of the Polar Sea.

I now turned my mind to wind conditions, for I knew they were a matter of interest to all those contemplating the feasibility of a polar airway. We found them good. There were no bumps in the air. This was as we had anticipated, for the flatness of the ice and the Arctic temperature was not conducive to air currents, such as are sometimes found over land. Had we struck an Arctic gale, I cannot say what the result would have been as far as air roughness is concerned. Of course we still had the advantage of spring and 24-hour daylight.

It was time now to relieve Bennett again at the wheel, not only that he might stretch his legs, but so that he could pour gasoline into the tanks from the five-gallon tins stowed all over the cabin. Empty cans were thrown overboard to get rid of the weight, small though it was.

Frequently I was able to check myself on the course by holding the sun-compass in one hand and steering with the other.

I had time now leisurely to examine the ice pack and eagerly sought signs of life, a polar-bear, a seal, or birds flying, but could see none.

On one occasion, as I turned to look over the side, my arm struck some object in my left breast pocket. It was filled with good-luck pieces!

I am not superstitious, I believe. No explorer, however, can go off without such articles. Among my trinkets was a religious medal put there by a friend. It belonged to his fiancée and he firmly believed it would get me through. There was also a tiny horseshoe made by a famous blacksmith. Attached to the pocket was a little coin taken by Peary, pinned to his shirt, on his trip to the North Pole.

When Bennett had finished pouring and figuring the gasoline consumption, he took the wheel again. I went back to the incessant navigating. So much did I sight down on the dazzling snow that I had a slight attack of snow blindness. But I need not have suffered, as I had brought along the proper kind of amber goggles.

Twice during the next two hours I relieved Bennett at the wheel. When I took it the fourth time, he smiled as he went aft. “I would rather have Floyd with me,” I thought, “than any other man in the world.”

We were now getting into areas never before viewed by mortal eye. The feelings of an explorer superseded the aviator’s. I became conscious of that extraordinary exhilaration which comes from looking into virgin territory. At that moment I felt repaid for all our toil.

At the end of this unknown area lay our goal, somewhere beyond the shimmering horizon. We were opening unexplored regions at the rate of nearly 10,000 square miles an hour, and were experiencing the incomparable satisfaction of searching for new land. Once, for a moment, I mistook a distant, vague, low-lying cloud formation for the white peaks of a far-away land.

I had a momentary sensation of great triumph. If I could explain the feeling I had at this time, the much-asked question would be answered: “What is this Arctic craze so many men get?”

The sun was still shining brightly. Surely fate was good to us, for without the sun our quest of the Pole would have been hopeless.

To the right, somewhere, the rays of the midnight sun shone down on the scenes of Nansen’s heroic struggles to reach the goal that we were approaching with the ease of an eagle at the rate of nearly 100 miles an hour. To our left, lay Peary’s oft-traveled trail.

When I went back to my navigating, I compared the magnetic compass with the sun-compass and found that the westerly error in the former had nearly doubled since reaching the edge of the ice pack, where it had been eleven degrees westerly.

When our calculations showed us to be about an hour from the Pole, I noticed through the cabin window a bad leak in the oil tank of the starboard motor. Bennett confirmed my fears. He wrote: “That motor will stop.”

Bennett then suggested that we try a landing to fix the leak. But I had seen too many expeditions fail by landing. We decided to keep on for the Pole. We would be in no worse fix should we come down near the Pole than we would be if we had a forced landing where we were.

When I took to the wheel again I kept my eyes glued on that oil leak and the oil-pressure indicator. Should the pressure drop, we would lose the motor immediately. It fascinated me. There was no doubt in my mind that the oil pressure would drop any moment. But the prize was actually in sight. We could not turn back.

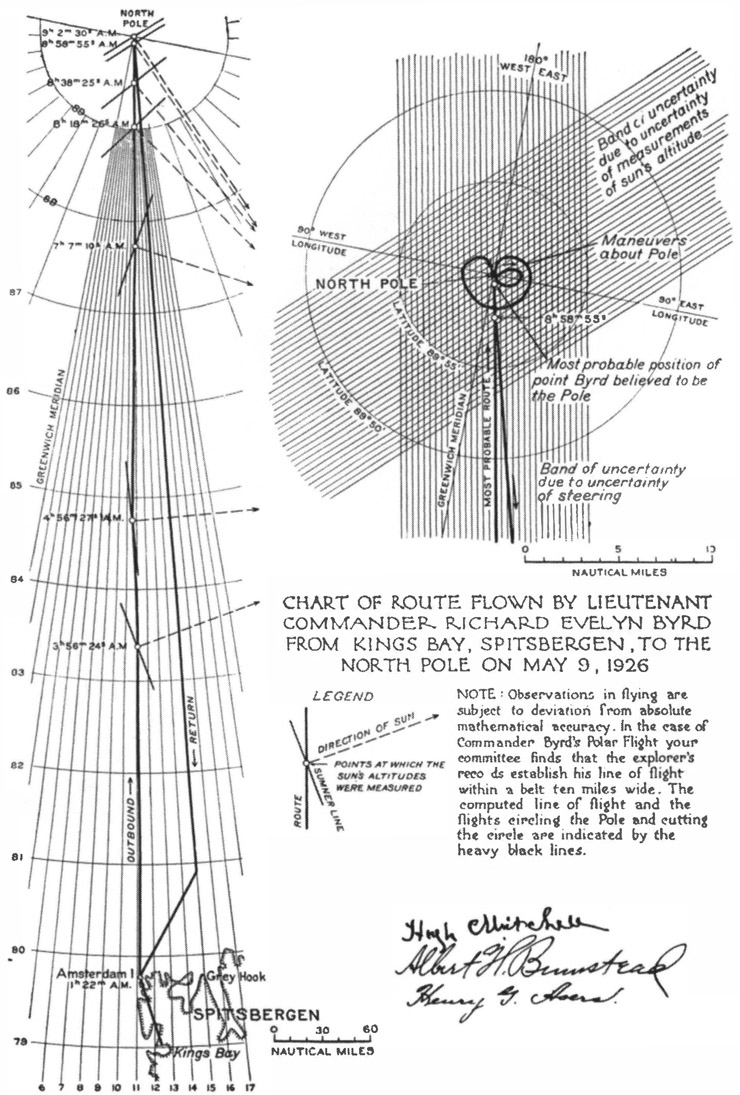

At 9.02 A.M., May 9, 1926, Greenwich civil time, our calculations showed us to be at the Pole! The dream of a lifetime had at last been realized.

We headed to the right to take two confirming sights of the sun, then turned and took two more.

After that we made some moving and still pictures, then went on for several miles in the direction we had come, and made another larger circle to be sure to take in the Pole. We thus made a non-stop flight around the world in a very few minutes. In doing that we lost a whole day in time and of course when we completed the cricle we gained that day back again.

Time and direction became topsy-turvy at the Pole. When crossing it on the same straight line we were going north one instant and south the next! No matter how the wind strikes you at the North Pole it must be traveling north and however you turn your head you must be looking south and our job was to get back to the small island of Spitzbergen which lay somewhere south of us!

There were two great questions that confronted us now: Were we exactly where we thought we were? If not—and could we be absolutely certain?—we would miss Spitzbergen. And even if we were on a straight course, would that engine stop? It seemed certain that it would.

As we flew there at the top of the world, we saluted the gallant, indomitable spirit of Peary and verified his report in every detail.

Below us was a great eternally frozen, snow-covered ocean, broken into ice fields or cakes of various sizes and shapes, the boundaries of which were the ridges formed by the great pressure of one cake upon another. This showed a constant ice movement and indicated the non-proximity of land. Here and there, instead of a pressing together of the ice fields, there was a separation, leaving a water-lead which had been recently frozen over and showing green and greenish-blue against the white of the snow. On some of the cakes were ice hummocks and rough masses of jumbled snow and ice.

At 9:15 A.M. we headed for Spitzbergen, having abandoned the plan to return via Cape Morris Jesup on account of the oil leak.

But, to our astonishment, a miracle was happening. That motor was still running. It is a hundred to one shot that a leaky engine such as ours means a motor stoppage. It is generally an oil lead that breaks. We afterward found out the leak was caused by a rivet jarring out of its hole, and when the oil got down to the level of the hole it stopped leaking. Flight Engineer Noville had put an extra amount of oil in an extra tank.

The reaction of having accomplished our mission, together with the narcotic effect of the motors, made us drowsy when we were steering. I dozed off once at the wheel and had to relieve Bennett several times because of his sleepiness.

I quote from my impressions cabled to the United States on our return to Kings Bay:

“The wind began to freshen and change direction soon after we left the Pole, and soon we were making over 100 miles an hour.

“The elements were surely smiling that day on us, two insignificant specks of mortality flying there over that great, vast, white area in a small plane with only one companion, speechless and deaf from the motors, just a dot in the center of 10,000 square miles of visible desolation.

“We felt no larger than a pinpoint and as lonely as the tomb; as remote and detached as a star.

“Here, in another world, far from the herds of people, the smallnesses of life fell from our shoulders. What wonder that we felt no great emotion of achievement or fear of death that lay stretched beneath us, but instead, impersonal, disembodied. On, on we went. It seemed forever onward.

“Our great speed had the effect of quickening our mental processes, so that a minute appeared as many minutes, and I realized fully then that time is only a relative thing. An instant can be an age, an age an instant.”

We were aiming for Grey Point, Spitzbergen, and finally when we saw it dead ahead, we knew that we had been able to keep on our course! That we were exactly where we had thought we were!

It was a wonderful relief not to have to navigate any more. We came into Kings Bay flying at about 4,000 feet. The tiny village was a welcome sight, but not so much so as the good old Chantier that looked so small beneath. I could see the steam from her welcoming and, I knew, joyous whistle.

It seemed but a few moments until we were in the arms of our comrades, who carried us with wild joy down the snow runway they had worked so hard to make. Amundsen and Lincoln Ellsworth, two good sports.

In a sentimental sense this ended the polar flight. But I was schooled too well in the troubles of other Arctic explorers to permit myself to believe that my job was done until I had the scientific approval of proper authorities.

On my return to New York I sent a radio asking that an officer messenger come for my charts and records. The Navy Department complied. Through the Secretary of the Navy I submitted everything to the National Geographic Society. The papers were referred to a special committee of the Society, consisting of its President, Dr. Gilbert Grosvenor, the Chairman of its Research Committee, Dr. Frederick Coville, and Col. E. Lester Jones, a member of the Board of Trustees, who is also Director of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey.

This committee appointed a sub-committee of expert mathematicians and calculators. The final report was submitted to the Secretary of the Navy and read in part as follows:

“We have the honor of submitting the following report of our examination of Lieutenant Commander Richard Evelyn Byrd’s ‘Navigation Report of Flight to Pole.’ We have carefully examined Commander Byrd’s original records of his observations en route to and from the North Pole. These records are contained on two charts on which Commander Byrd wrote his observations, made his calculations, and plotted his positions. We have verified all his computations. We have also made a satisfactory examination of the sextant and sun-compass used by Commander Byrd.

“At 8 hours 58 minutes 55 seconds May 9, 1926, an observation of the altitude of the sun gave a latitude of 89° 55.3’ on the meridian of flight. This point is 4.7 miles from the Pole. Continuing his flight on the same course and at the speed of 74 miles per hour, which he had averaged since 8 hours 18 minutes, would bring Commander Byrd close to the Pole in 3 minutes 49 seconds, making the probable time of his arrival at the Pole 9 hours 3 minutes, Greenwich civil time.

“At the time Commander Byrd was close to the Pole he estimated the moment of his arrival there at 9 hours 2 minutes. Our calculations differ from his estimate less than one minute, during which time he would have flown about one mile. From this it appears that he chose the right place to maneuver.

“Flying his plane to the right long enough to take two sextant observations, he turned around and took two more observations. These four observations confirmed his dead-reckoning position of the Pole. He then attempted to fly his plane in a circle several miles in diameter, with his Pole position as a center.

“Flying at and about the Pole at an altitude of 3,000 feet, Commander Byrd’s field of view was a circle more than 120 miles in diameter. The exact point of the North Pole was close to the center of this circle, and in his near foreground and during more than two hours of his flight was within his ken.

“Soon after leaving the Pole, the sextant which Commander Byrd was using slid off the chart table, breaking the horizon glass. This made it necessary to navigate the return trip wholly by dead reckoning.

“In accomplishing this, two incidents should be specially noted. At the moment when the sun would be crossing the I 5th meridian, along which he had laid his course, he had the plane steadied, pointing directly toward the sun, and observed at the same instant that the shadow on the sun-compass was down the middle of the hand, thus verifying his position as being on that meridian. This had an even more satisfactory verification when, at about 14 hours 30 minutes, G.C.T., he sighted land dead ahead and soon identified Grey Point (Grey Hook), Spitzbergen, just west of the 15th meridian.

“It is unfortunate that no sextant observations could be made on the return trip; but the successful landfall at Grey Hook demonstrates Commander Byrd’s skill in navigating along a predetermined course, and in our opinion is one of the strongest evidences that he was equally successful in his flight northward.

“The feat of flying a plane 600 miles from land and returning directly to the point aimed for is a remarkable exhibition of skillful navigation and shows beyond a reasonable doubt that he knew where he was at all times during the flight.

“It is the opinion of your committee that at very close to 9 hours 3 minutes, Greenwich civil time, May 9, 1926, Lieutenant Commander Richard Evelyn Byrd was at the North Pole, insofar as an observer in an airplane, using the most accurate instruments and methods available for determining his position, could ascertain.”

We have secured the author’s permission to introduce at this point what we consider an essential part of the record: viz., report of presentation of the Hubbard Medal in Washington, and the President’s speech on this occasion. Later the thanks of Congress were given Byrd and he was promoted to the rank of Commander, U. S. Navy, and the Congressional Medal of Honor presented.

In the presence of 6,000 members and friends of the National Geographic Society, including the President of the United States, members of the Cabinet, distinguished Army and Navy officers, members of Congress, ambassadors and ministers of foreign countries, and other representatives of official life in the National Capital, Commander Richard Evelyn Byrd, Jr., received the Society’s Hubbard Gold Medal in the Washington Auditorium on the evening of his return to America, June 23, after his flight to the North Pole.

On the same occasion the explorer’s associate, Aviation Pilot Floyd Bennett, also received a gold medal. Only six other men have ever received the Hubbard Medal. They were Admiral (then Commander) Robert E. Peary, Captain Roald Amundsen, Vilhjalmur Stefansson, Captain Ernest H. Shackleton, Grove Karl Gilbert, and Capt. Robert A. Bartlett.

President Coolidge in presenting the medals said:

“Word that the North Pole had been reached by airplane for the first time was flashed around the globe on May 9. An American naval officer had flown over the top of the world. He had attained in a flight of fifteen hours and thirty minutes what Admiral Peary, also a representative of our Navy, achieved, seventeen years before, only after weary months of travel over the frozen Arctic wastes.

“The thrill following the receipt of this news was shared by everyone everywhere. It was the spontaneous tribute to a brave man for a daring feat. We, his countrymen, were particularly proud. This man, with a record of distinguished service in the development of aeronautics, had by his crowning act added luster to the brilliant history of the American Navy.

“In no way could we have had a more striking illustration of the scientific and mechanical progress since the year 1909. Then Peary’s trip to the Pole on dog sleds took about two-thirds of a year. He reached his goal on April 6. It was September 6 before news of the achievement reached the outside world.

“The naval officer of 1926, using an American invention, the airplane, winged his way from his base, at Kings Bay, Spitzbergen, and back again in less than two-thirds of a day; and a few hours later the radio had announced the triumph to the four quarters of the earth. Scientific instruments perfected by this navigator and one by a representative of this organization were in no small degree responsible for success.

“We cannot but admire the superb courage of the man willing to set forth on such a great adventure in the unexplored realms of the air; but we must not forget, nor fail to appreciate, the vision and persistence which led him ultimately to achieve the dream of his Naval Academy days. He never ceased the effort to prepare himself mentally, scientifically, and physically to meet the supreme test. His deed will be but the beginning of scientific exploration considered difficult of achievement before he proved the possibilities of the airplane.

“Lieutenant Commander Richard Evelyn Byrd, your record as an officer and as a man is illustrious. You have brought things to pass. It is particularly gratifying to me to have this privilege of welcoming you home and of congratulating you on behalf of an admiring country, and to have the honor of presenting to you the Hubbard Medal of the National Geographic Society.

“And I take further pleasure in presenting to you, Mr. Floyd Bennett, aviation pilot, U. S. N., this medal, awarded to you by the National Geographic Society for your distinguished service in assisting and in flying to the North Pole with Mr. Byrd.”