BEFORE the Chantier had steamed many miles toward home, I began to realize that we had stirred up something by flying to the Pole. First there were radios of congratulation and good wishes. Then radios of inquiry. And finally, radios that literally ordered me to do things I had never even dreamed of doing, couldn’t do even if I wanted—such as make a speech at three different banquets, to be held in three different cities on one and the same night. I felt rather stunned about it; but, of course, greatly appreciative.

It was all more of a surprise than people could realize. To go back for a moment: When I broke my leg at Annapolis I was only trying to best the other fellow. When I crowded into aviation during the war I was only satisfying my great desire to fly and at the same time doing what any patriotic American would do to help his country. When I took charge of the navigational preparations of the Navy’s trans-Atlantic flight in 1919, I believed I was contributing to my service and to the art of flying. I felt pretty much the same about my Greenland work and during my preparations to fly to the North Pole.

Now I discovered that success of our flight from Spitzbergen touched some responsive public chord which loosed a torrent of attention upon me and my expedition. I was much pleased, of course. But I was also astonished, and secretly worried. My fear was that personal notoriety might overlay the good I had hoped to do for aviation.

I wondered exactly what it all meant. What I ultimately found out about “being a hero” gave me almost as much of a “kick” as did the sensation of circling the Pole.

We arrived at New York on the morning of June 22, 1926. We were met by the mayor’s official tug, the Macom, on board of which were several official welcoming committees, a delegation of senators and representatives from Congress, a regiment of newspaper reporters, and enough photographers to man a battleship.

For half an hour I was tossed about like a leaf in a storm. Then a friend cornered me. I could see he was laboring under high tension. He spoke feverishly:

“We arrive at the Battery at noon. You will be presented with a medal and the keys to the city at twelve-fifteen. You will make two speeches in reply. At lunch you will make another speech. At four-thirty-two we leave for Washington. On arrival you will be met by a committee of welcome. Twenty minutes later President Coolidge will present you with a gold medal. You will make a speech—”

“But I’m not a speech maker,” I protested.

My friend seemed to grind his teeth. “Makes not the slightest difference,” he snapped. “You are now a national hero. You—”

I felt myself whirled bodily about. “Look up, Commander. Stick an eye on that airplane up there,” yelled someone.

Involuntarily I glanced skyward. Twenty cameras clicked.

A heavy man jostled against me. “I want you to meet the president of the—” He didn’t finish. I found myself grasping the hand of an important-looking individual.

“You are a national hero,” he declared. “I am pleased—”

“Be sure you speak of leaving this port in the mayor’s speech,” broke a hoarse whisper in one ear. My feverish friend again.

Before I could answer, the broad-shouldered chairman of the reception committee elbowed his way in.

“Excuse me, Commander, but these fellows want a picture of you and your mother.” Ten more cameras infiltrated through the crowd. I began to feel like a promising halfback who has to carry the ball at every down. Things began to be going more rapidly. Between the erupting fireboats, the airplanes and the yacht escorts I felt a stiff neck coming on. The whistles were deafening.

All of this was entirely unexpected. I felt bewildered. But most grateful that the nation should do all this for us. Of course, I didn’t take it all to myself. Far from it. There was Bennett by my side who deserved equally with me and perhaps more. Then there were our half hundred shipmates who had unselfishly put every ounce of their strength and energy into the job. Then my thought dwelt on the dozen or so other men who had formed necessary links in our success.

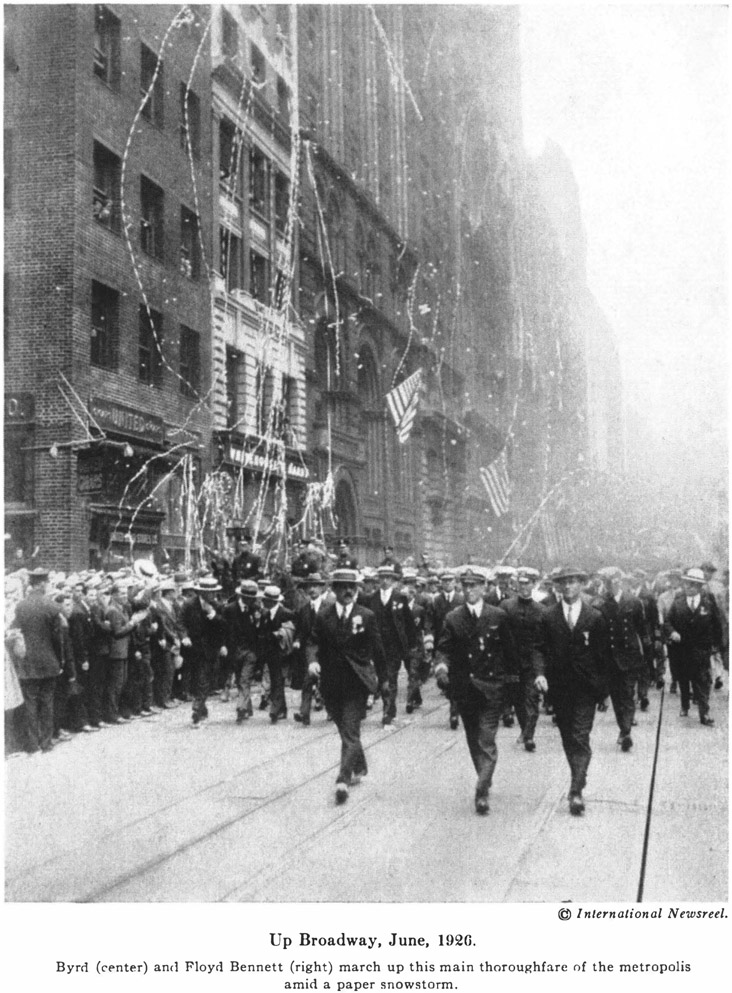

The scene at the Battery resembled a riot. A parade was formed. As we passed up Broadway the air grew thick with a blizzard of paper streamers and confetti. The sidewalks were packed with people. Traffic stopped.

The City Hall was surrounded by a dense mass of humanity. A cordon of mounted police kept open just enough space to let our party pass. We wound up into the ceremonial chambers. The auditorium was jammed to its doors. The oratory began….

And so on all that day, ending with President Coolidge’s presentation in Washington that night. And all the next day. And the next, and the next. The high point came in Richmond, Virginia, my native state. Thousands turned out the night we arrived. There were glare-lights, speeches and brass bands; a swirling friendly multitude.

What did it mean? I asked myself the question; but could find no answer. I asked my friends. But all they would reply was the same refrain in one form or another, “Don’t you know you are a national hero now?”

Of course I realized that an adventure like our polar flight aroused great public interest. I knew before I left that there would be a certain amount of risk in crossing the polar ice, just as there is in any flight over an unknown terrain. I had a notion that such a stunt is great stuff for the publicity people.

But my idea of a national hero was somebody like George Washington or John J. Pershing. They had held the safety of our country in their hands. They had suffered the agony of long campaigns. They had led armies to victory against a public enemy.

We hadn’t done anything so valiant.

“But what is a national hero, and why? “ I asked a newspaper friend of mine.

“Oh, someone who’s worth two columns and a front-page streamer, fireboats and a basket of medals,” came the cynical reply.

But I wasn’t satisfied; not when I thought of the thousands of American citizens who had grasped my hand since my return; and of the tens of thousands of jubilant letters and telegrams that had reached me.

No, there was something more, something deeper.

The first inkling of the great discovery came in Washington just before I faced the President and a large audience of distinguished diplomats. I had never spoken before so august an assemblage. To rehearse some of the thoughts that crowded my mind, I managed to sneak away for a few moments in the stage wings of the giant auditorium where the ceremony was being held. I stood in a little bare alcove glancing over my notes. Suddenly a door behind me opened, then softly closed. I turned. Facing me stood a little white-haired lady in black bonnet and gown. Despite the age in her face, her eyes were brown and bright. They looked into mine unblinking.

“You are Commander Byrd?” she asked.

“Yes, madam. “

She came a step forward in a sudden wistful eagerness. “And you reached the North Pole? “

“There seems to be no doubt of it.”

Her lips parted as if to speak again. But before she could utter a word an abrupt change came over her. She gave a quick sigh. Her mouth trembled. She thrust out one hand as if to touch me. Her eyes dimmed and filled. Then she cried out:

“Oh, I’m so glad!” Before I could stop her she was gone.

I heard a step behind me. “All right, Byrd.” The same irritating whiplash of necessity that notoriety brings. “The President is arriving. You will have to go on the stage at once.”

I went on the stage. But the mystery of the little lady in black clung to me. I espied her in the audience. I managed to inquire about her during a lull in the ponderous proceedings of the evening.

“Poor thing,” whispered my informant. “She’s had a tough break in life. Lost her husband twenty years ago. Brought up two fine boys on what she could make herself. Lost both of them in the World War. Now she’s all alone.”

In a flash of understanding I knew something of the answer to my question: What is a national hero?

I was a hero to that sad little mother, but not in a way the word is usually used. No doubt she admired us for having succeeded. Probably the story of it all gave her daily newspaper a fresh flavor. Possibly she speculated over what it felt like to fly. But those weren’t the things that made her seek me out and face me first-hand with her gladness.

What that mother saw in me was the living memory of her husband and sons. They had been splendid men. I later learned that they had been adventurous and so were the kind who would have liked to have flown to the North Pole. They were fine, keen, courageous men. And if they were all that to the passing acquaintance who retailed their virtues to me, what demigods must they have been to that little white-haired lady.

To her I was the living flesh she so longed to touch. I, she knew, was son and husband. Now she would sit out there among a great throng and listen while the President of the United States extolled Bennett and me, even as she might have sat and listened had Fate been equally generous to her.

It may sound incredible, but in that moment I got the philosophy of the thing. I had been human in my home-coming. The grand public welcome had moved me, though I had felt humble and more or less undeserving of such recognition. I had had to pinch myself every now and then to see if it were all true. I had felt like a man who had unexpectedly reached a mountain top and finds a gorgeous panorama spread before his eyes. I had wanted to throw my hat in the air and shout, “Gosh, but this is great!”

Now, in a trice, another man’s mother had wiped away my smug acceptance of unexpected fame.

My memory sprang back to Annapolis days. I recalled the first time I marched down the town street as color bearer. The band was playing. As I passed, men uncovered, ladies applauded, children waved their hands. I was stirred by this show of admiration. Pride filled me. I seemed walking on the air. I felt brave, superior, triumphant. Then with a thump, came the truth. People weren’t saluting and cheering me. They were saluting the Stars and Stripes which I carried.

Exactly that was happening now. The cheers and the handclasps, the waving hats and flags, the music and the speeches, weren’t really meant for me any more now than that boyhood morning in Annapolis when I marched at the head of the procession holding aloft the flag of my country. The banner I carried now wasn’t so visible, nor easily painted. It didn’t in its symbolism depict the stormy history of a people. It never would stir a nation to righteous indignation against an invader. It couldn’t be nailed to the mast of a sinking ship.

No, my banner was none of these. In our success people saw success that might have been their own. In Bennett and me mothers saw their sons, wives their husbands, sisters their brothers. In us men saw what they too might have done had they had the chance. In us youth saw ambition realized.

In us America for the moment dramatized that superb world-conquering fire which is American spirit. For the moment we seemed to have caught up the banner of American progress. For the moment we appeared to typify to them the spirit of America.

It was great to think that, even for these precious moments, we were destined to carry the banner.

Was I proud? Of course. But humble, grateful. There were a half hundred members of our expedition who deserved equally with me to carry that banner.

Now that my eyes were opened I began to look about for more manifestations of this discovery of mine. I went to the Middle West to lecture. In a small town off the beaten track I stopped for a one-night stay. A leading citizen drove me about just before sunset.

“We are very proud of our parkways,” he said. “They are all built by personal contribution. Those who can’t give money contribute their services. By the way, the engineer of our steam roller told me the other day he hoped I’d introduce him to you when you came here.”

“Why not see him now?” I suggested. The thought of the people building their home town’s boulevards by pure community spirit appealed to my imagination.

We drove to a frame bungalow near the edge of the town. Two urchins hung on the gates of an untidy yard. A tired-looking woman with a kindly smile met us at the door. Two more urchins clung to her skirt.

“Come right in. Jim’s just back from the factory. He’ll be out soon’s he’s changed his shirt.”

Jim came in wiping his hands. He was tall and lean. His whole face lit up when his townsman introduced me.

“Commander Byrd speaks at eight,” said my escort. “Don’t forget.” Jim nodded, his eyes fixed on my face. His wife must have felt the strain of the situation; her husband’s sudden inarticulate silence.

She made a few irrelevant remarks, then suddenly turned to him: “Jim, tell Commander Byrd about your invention.”

Jim flushed. He began to talk, haltingly at first, about a scheme for vertical flight, a sort of helicopter. He had a small workshop out in the woodshed. He was building a model of his device.

“You ought to get someone to back you,” I told him. “If the idea is practicable the right sort of engineering assistance will put it through in no time.”

“But that isn’t it.” Jim put up his hands as if to shape the thought he could not accurately convey in words.

His wife broke in with, “I told him that very thing.”

Jim’s fingers groped. He said:

“It isn’t a question of money. It’s somebody to look ahead and see what we’re coming to.” The words were tumbling out now. “All they think of is profits. One man turned me down because he said it wouldn’t pay dividends this year.

“Another said he’d pay me a big lump sum if I’d give him what I’d worked out so far. They’re both wrong.

“I want to move slowly. The Wrights did when they started. They could have sold out early to an amusement company. We wouldn’t have been flying today if they had.”

The wife was angry now. “Don’t go on like that,” she said.

But Jim could not be stopped. I didn’t want to stop him. He poured out his whole story, a lifetime of struggle and hard work. Yet he could not sacrifice his idea for quick gain.

We had to break away before he finished. As we drove back my friend the leading citizen said: “I have known him for years. That is the first time he has ever loosened up. You see what it is, of course. He thinks you would do the same as he is doing if you were in his boots. I believe your visit helped him.”

That gave me my second cue to appreciation of my discovery, and again I felt humble and grateful. Listening became one of the best things I did. What a paradox it was too! I had always looked on the returned explorer as a sort of traveling oracle. True, people seemed to like my films of the flight and politely followed my yarn of how we reached the Pole and returned. There were speeches of introduction beforehand, and handshaking afterward. But these were routine. The interesting moments I looked forward to were where someone got me off in a corner and told his story.

These stories were superior to mine. Mine was hemmed in by realities like time and distance, whereas the others were usually bounded only by the elastic horizon of human imagination.

It would take a dozen thick volumes to record all my experiences that confirm that discovery I had made in Washington. My mail alone in the months since my return contains a thousand stories of human happiness, hope and heartbreak.

“Why don’t you get out a form letter thanking these people who write you?” suggested an efficient friend of mine.

Coincidence played into my hands. I handed him two letters I had just opened. “Read these and you will understand.”

He read aloud:

Dear Captain Byrd: You never heard of me, and will probably never see me. I keep house for my two brothers. Our mother and father are dead. It may sound silly to tell you such things, but all last winter we have had a hard time. One of my brothers lost his job. The other had an abscess on his back and couldn’t work for several months. Then we began reading about your plans and later about your fine trip to the North Pole. I have to work so much there is no chance to get about. We have lived your adventures with you. It has been fun and I want to thank you and wish you luck on your next flight.

Then he read the other letter which was typical of thousands I had received from boys and girls:

My dear Commander: I like you. I like your trip to the North Pole. I have made a model of the Josephine Ford. Will you please put your name on a piece of paper so that I can paste it on my little airplane. I hope you get across the Atlantic all right. I know you will. I will be reading about you.

My friend tossed the letters back. “Sounds like testimonials for a patent medicine,” he said skeptically.

“It might,” said I, “if there were only these two. But there are hundreds. Many talk like that when I meet them. The adventures have a real meaning to many people and to all the great youngsters.

“Well you’re a national hero, aren’t you? Isn’t that what does it?“

I looked in the eye. “I’m really only carrying the banner for a little while,” said I.

He looked at me as if I had suddenly lost my mind. “The what? “

A tumult in the street below our window put an end to our talk. We looked out. I knew what was happening.

In the sunshine flags twinkled. Black ribbons of humanity lined the avenue. At upper windows were crowding faces. Extra traffic men pranced to and fro. Long gay streamers of confetti floated down from the skyscrapers. A band flashed into view. The quick march it played was the music of victory. Uniformed ranks swung rhythmically behind the band. Then came a column of automobiles.

In the leading car, framed with flowers, stood a sturdy youthful figure, arms outstretched to the cheering multitude. It was Gertrude Ederle.

I leaned far out. I wanted to shout a message, to deliver something I had been holding.

I wanted to shout: “Here is the banner!” and cast that invisible something into the outstretched hands of the girl in the leading car.

But I did not need to. The lusty throats of ten thousand Americans were shouting my message. And the banner was already in the hands of its next fortunate bearer.

That’s what this hero business means.