THE public loves the drama of dangerous adventure—as described on the printed page. The perilous part of exploration is also the adventurer’s greatest joy. Of the toil and the anxiety that now go into the organization of a big expedition the public hears but little. Of the anguish the leader must suffer in this preparatory phase none can know who has not been through it.

In my big library of Arctic books I find that one poignant similarity joins them all as a class. On the final field map of each thrilling expedition one fatal spot is usually denoted as that at which came the climax of the leader’s grim success or galling failure.

I choose at random: “X marks the spot where our brave men died after six days of howling blizzard and bitter cold.”

But, alas, like styles on the boulevard, so have styles in exploration changed. How profound has been the change can be indicated in no better way than by the fact that the X that used to mark the spot where the dying explorer ate his last morsel of pemmican now marks the office where he collected his last dollar of backing.

Exploration has always been a battle between man and the elements. It is now; except that chilblains and thirst have given away to creditors and thrift. Sixty below zero still makes the brave leader quake. But his zero isn’t on the thermometer, but on the credit side of his expeditionary ledger.

It cost Columbus $2,115 to discover America. It cost the world $200,000,000 and hundreds of lives to discover the North Pole. I don’t intend to argue that either was worth more or less than it cost, but the overhead of polar work hasn’t gone down since the date of Peary’s discovery.

My North Pole expedition in 1926 was made just about as cheaply as possible. We spent hours and hours trying to get things done economically. It had to be. Yet it cost in cold cash about $140,000. Nor does this take in a very large sum represented by men and material which were given at cost or donated. For a few weeks at sea and a few hours in the air such expense is high.

Our trip to the South Pole will cost above $450,000. As we have to be ready to winter on the Antarctic ice barrier and cover about 24,000 miles in the round trip from New York, the cost rises much beyond that of a North Polar party.

There was much hue and cry a few years ago over the ease and economy air travel would bring to the explorer. It looked as if so much time would be saved and so little work have to be done in the hard winter seasons that one of my dollars would now do the work of four or five of Peary’s.

But we were all wrong. The first thing that happened was that the expedition ship had to be bigger in order to carry an exploring plane to the base of operations. A larger ship meant more men, more fuel, more repairs.

Another costly item was the mechanical extravagance of the new vehicle. The old explorer never made 100 miles an hour, but his hour-mile cost more than 100 times less. There was nothing of the prima donna in the sledge. It could be pushed or pulled until it fell to pieces. Its only fuel went into the leather-lined bellies of its draft animals and its lubrication was Nature’s own snow fields. The whiplash was its throttle, and all the overhauling one did after a trip was to tighten up a sealskin lashing and hammer a bent runner into shape with a granite bowlder.

There are something like 2 ,000 integral parts in a modem airplane. At any time some 300 of these may get out of commission. At least 800 of them have to be replaced if broken. Repairing one part may mean the readjustment of fifty others. With the nearest airplane factory more than 2,000 miles away, one has to take plenty of spares. The old proverb read, “For want of a nail the shoe was lost,” and ended by blaming the rider’s demise on this tiny item. Exploration by air can be equally fatal for the want of a part a good deal smaller than a horseshoe nail.

The old explorer never faced complete failure so steadily as does the modern flying leader, who literally has all his eggs in one or two very expensive baskets. By sledge or back pack it was always possible to accomplish at least a part of the original plan. But let one serious crash come to the aeronautical side of a modern expedition and there is nothing left to do but go home and face the music.

On our North Pole trip Bennett and I were not half so worried about breaking our necks on the polar ice as we were about smashing our plane on the take-off. Our big three-engined monoplane was equipped with skis which we hadn’t yet learned to use. Three times we came within a hairbreadth of cracking up before we got away for the top of the globe. Had we done so, the expedition would have ended then and there. My news rights and films and lectures with which I hoped to stave off a small army of creditors wouldn’t have been worth a backstay’s bight.

It would have given some of these same creditors St. Vitus’ dance to see us bring our expensive plane ashore through half a mile of loose ice between the ship and the shore. We made a raft that did the trick, after some hair-raising setbacks when the big floes started out with the tide. This time X marked the spot not where we were cold and wet and in imminent danger of drowning among the growlers, but where we escaped by our teeth from nearly plunging into a financial abyss from which I personally might not have emerged for many years.

An explorer has always been a geographer. He was also expected to be on speaking terms with the flora and fauna of the region which he was to penetrate. He had to have medical knowledge in case of emergency, and be prepared to deal with any form of crises from putting down a mutiny to considering an offer of kingship over a savage tribe.

When the twentieth century opened with primus stoves and percolators, electric generators and spectroscopes among the essentials of an explorer’s kit, the professorial aspects of his job began to weigh heavily. When another decade brought radio, with its tubes, counterpoises and condensers, the successful adventurer was less a two-fisted leader than a six-cylinder physicist. With the introduction of flying into the exploring field, no outstanding explorer could equip his party economically without knowing most of the principles of aeronautical dynamics in addition to all the burden of other sciences under which his predecessors labored.

Naturally an outdoor man, the modern explorer has now to learn to be an indoor man. He must attend numerous functions and ceremonies where he generally has to make a speech. He is expected to be able to talk well on any subject. He must lecture to raise funds for his expedition. For the same reason he writes for newspapers, magazines, and every now and then he produces a book. He therefore must be able to write. But the last straw has come in the past few years with the terrific financial complexities which have changed exploration from a species of research to something resembling a stock-market manipulation. If he does not administer the business affairs of his expedition economically, he is likely to go on the rocks a bankrupt. History proves this point only too poignantly. Columbus died penniless. Scott, perishing on the Antarctic ice, penned a message to the English nation pleading that his family be cared for. Shackleton, dying in harness, left an estate too slight to keep his wife and child. Amundsen, Rasmussen, Stefansson, Capt. Bob Bartlett and a dozen others who have devoted their lives to the spread of human knowledge through the median of exploration are all poor men.

The paradox of the whole thing is that the true explorer usually has ideals enough not to want to commercialize his work.

There are several legitimate ways to raise funds that cannot logically be condemned. Lectures are a medium through which many conservative people may be reached who otherwise would have some difficulty in following first-hand an explorer’s work. Films, magazine articles and still pictures are of more or less value, depending on the skill and perfection with which they are produced and distributed. The expedition leader’s newspaper stories, when properly handled, bring good prices and give the public well-directed information of an expedition’s progress in the field. Such stories cannot be given away. They must be exclusive to be of any value.

The radio has introduced another consideration—the spot news; that is, the day-by-day news of the expedition. Formerly the Arctic explorer could not give the daily happenings of his expedition to the world. When I go to the Antarctic I shall have my base 2,300 miles from the nearest human dwelling. But I hope to get back interesting reports of how we are progressing.

These legitimate fund-raising methods are by no means assured profits. A newspaper story worth $30,000 if an expedition is dramatically successful, may be worth less than $3,000 in case of unavoidable failures. Contracts are drawn in advance, making price contingent on results. The same applies to lectures. If there be no story to tell or no film to portray the story, a tour may well shrink to half a dozen friendly engagements given with little or no profit.

It is clear then that the modern explorer cannot force his burden of debt on other shoulders by simply discounting his news, film and lecture success. Were he able to do so, the wilderness would be populous with fantastic expeditions. Little does the public realize the widespread craze to explore today. What holds most amateurs in check is purely the problem of where to get the money.

Almost the only way to finance a modern expedition is to get subscriptions from private citizens, institutions and associations altruistically interested in pure science. It is easy to picture Mr. Millionaire giving a big sum to applied science. In such an investment he always has a chance of making a killing if the research be a success. But contributions to Arctic exploration are generally made unselfishly, without any chance of dividends.

But before the leader can approach a prospective contributor he must have established on one hand his ability to do the job and on the other the authenticity of his plans.

In my own case I struggled through a maze of red tape in 1925 before finally emerging with Secretary Wilbur’s approval. Officialdom was kind enough individually, but for complexity, the mills of the gods that grind so slowly give a modern printing press a puerile simplicity. What I wanted to do was to command the naval aviation unit of the National Geographic Society’s expedition, then bound for North Greenland.

“I will go to the President,” the secretary told me, signifying I had reached the last barrier.

But I was none too sanguine. President Coolidge’s ideas of economy and his natural reluctance to let his military personnel take undue risks made me feel that my chances of getting away were none too bright.

When the secretary took the matter to him the critical moment had been reached, the moment of which I had been dreaming for years. If only I could go on this one expedition, I knew I might have a chance in the following year to realize my cherished hope of some day flying to the North Pole.

The secretary told me later about his interview with his chief. He went thoroughly into detail.

“There is still a great deal of blank space on our polar map, Mr. President. Don’t you think we ought to let Byrd go?” he concluded. In complete silence the President had listened, yet with attentiveness.

After a moment of thought the President nodded to his cabinet officer and said “Why not?”

No discussion, no questions. Just that pair of words which for prodigious consequences in my life compare favorably with the other well-known couple: “I do.”

The President’s tacit approval of my plan enabled me to get prompt orders to go north. Between these orders and the press announcements I had something sound on which to base my collection of equipment. Luckily I needed no money, since the Navy was going to let me have my men, equipment and planes. We got away in the early summer and, as previously stated, managed to fly with the three machines more than 5,000 miles—the first extensive Arctic aviation up to that time.

I might mention here that, like wars, expeditions into polar regions are won by preparations, though it is of course natural that the zero hour—the final dash—gets the spotlight. Yet behind the scenes there is frequently the more interesting drama, and even zero hours unwritten and unknown may be found there. It is not in order to go into the infinite detail connected with a polar expedition, but I will touch briefly on some of my business experiences.

The year after our 1925 expedition Bennett and I launched our plan to conquer the North Pole by air. The first man I tackled was Edsel Ford. He was near my own age, a big man with ideals, and son of a father who thought in terms of America’s tomorrow.

It was a big moment. Should he deny a subscription, there would be no 1926 expedition for me. There were then four or five North Pole expeditions underway. I laid my cards on the table.

I told him frankly the plane I wanted to use, knowing that this was a machine in competition with the new Ford design. My reason for using that plane was that the particular plane I had in mind had been flown 15,000 miles—long enough to get the usual kinks out of it. It was a ticklish moment, asking a big man to finance a scheme that would be an advertisement for his competitor. He nodded gravely, but did not reply.

“And if we crack up on taking off our great plane with skis,” I confessed, “that’s the end of the party.”

It is significant of the man’s tolerant, broad character that when I finished he said simply:

“Certainly I will help you. I believe your expedition will do a lot to increase popular interest in aviation in America.”

Not only did Mr. Ford promptly give me the generous sum I asked for but he wrote a friend, urging him also to come in.

I was now in a position to condition the ship which the United States Shipping Board had so kindly put at my disposal and to order the provisions we had to have aboard in case we were forced to winter. But though I figured as carefully as I could, I soon found myself again in financial straits. Well I knew that almost regardless of expense my equipment must be of the very highest order. A tainted can of pemmican, a poorly sewed ice boot, a mitten without a lanyard, an oversize screw thread on some insignificant airplane part, might well spike my guns long after I had left the nearest civilized base of supplies.

More money had to be got. I had gone ahead too far to turn back; yet my credit was strained to its breaking point. Putting my pride in my pocket, I called on the president of one of our great corporations, a Crœsian cliff dweller on Broadway. In my pocket I fondled a warm letter of introduction from an old friend of the great man.

From nine A.M. until after noon I cooled my heels in the magnate’s plush-lined outer office. Painful waiting it was, too, with a thousand details of preparation clamoring for my attention. And there was none of the consolation that my men could sympathize with my apprehension as they could when later we faced the hazards of field work. I scarcely dared tell my best friend how thin my funds were for fear an adverse publicity might leak into the papers, which for years had been captious about the undue risks of Arctic work.

By a side door my quarry slipped out to luncheon, leaving word that he would see me in the afternoon. I waited. As the sun was sinking over the Hudson I got my final word—of dismissal. A colored messenger came out and told me that Mr. Blank had decided he couldn’t see me at all.

How different were my relations with John D. Rockefeller, Jr. The sequestration of great wealth in this country may infuriate demagogues; but whatever be its defects, the social system that makes rich men possible also makes possible the promotion of scientific endeavor that would scarce be thought of under a more general diffusion of wealth. I soon found that Mr. Rockefeller had made just as much a business of giving as the modern explorer must make of collecting. I believe that to give in such a way that progress will be helped instead of hindered is one of the most difficult and elusive things to accomplish. Being of a scientific tum of mind, Mr. Rockefeller has developed into a past master in the art of giving. But he is broad enough to value and heed advice from specialists, so he has hired some of the best brains in the country to help him decide what enterprises promise results and human profit, and what do not. Mr. Rockefeller came to my rescue by matching Mr. Ford’s contribution.

The thing that astonished me about these men, as well as others of their class with whom I have come in contact, is the wide disparity between the public’s picture of them and the men themselves. Edsel Ford, for instance, is the real directing head of the mammoth enterprise his father has built. He keeps longer office hours and works harder actively managing the Ford Motor Company than the average business man, yet he goes about it all so quietly and efficiently that the public knows scarcely anything about him.

Then take the young Mr. Rockefeller. Even fiction writers are chary about giving their heroes such a fortune as the Rockefeller estate. To the average man this wealth suggests a sort of Sybaritic solitude, full of gilded joys made sweet by a quintessence of ease. In contrast, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., slaves away daily just about like any other business man. He isn’t working at making money, but at the far more difficult task of supervising its scientific spending for progress. He is an excellent speaker. And his athletic prowess, on which any man can build a sane philosophy, he probably prizes higher than his fortune. He is a man of very high ideals and he lives up to them.

As the day of my departure north approached once more, I saw my liabilities outdistancing my assets. Perhaps there is something in telepathy, for about this time Vincent Astor sent for me and wanted to know how I was coming along.

“I’m worried about your finances,” he said, throwing down the guard that all rich men must wear. He had already made a substantial contribution to the expedition.

He offered to go on my note for any amount that I needed, asking no more than my signature. It was a strong temptation to accept. If things broke right in the north I should have no difficulty repaying the loan. But I admitted that my name had nothing back of it now that the expedition was already in debt. As with Edsel Ford, I further explained that a crash on our take-off in Spitzbergen would likely precipitate bankruptcy proceedings when we came back.

“What difference does that make?” he asked. “I’m simply betting on you, am I not?”

Again I saw how quickly and completely a big man can make up his mind on occasion.

Nine men and one woman subscribed for my polar flight. I know that all gave for unselfish reasons ; but some went so far as to refuse to let me even publish their names in connection with the enterprise. Among others who subscribed were Captain and Mrs. John H. Gibbons, U.S.N.; Thomas Fortune Ryan, a Virginian; and Richard Hoyt of New York.

I remember paying a call of pure courtesy on a rich citizen of Virginian descent two months before we sailed north. As I got up to leave he said quite unexpectedly:

“Byrd, I want to donate something to your expedition. But I will do it only on the condition that you do not mention me.”

I recall one night lecturing in Washington before the Massachusetts Society of the District of Columbia. To my surprise a Congressman I know hurried up and insisted that I let him give something toward my new adventure, as he put it. There is more than altruism in that sort of enthusiasm. I think it reveals a little of the love of romance lurking in the hearts of most people, far beneath the sleek enamel of civilization.

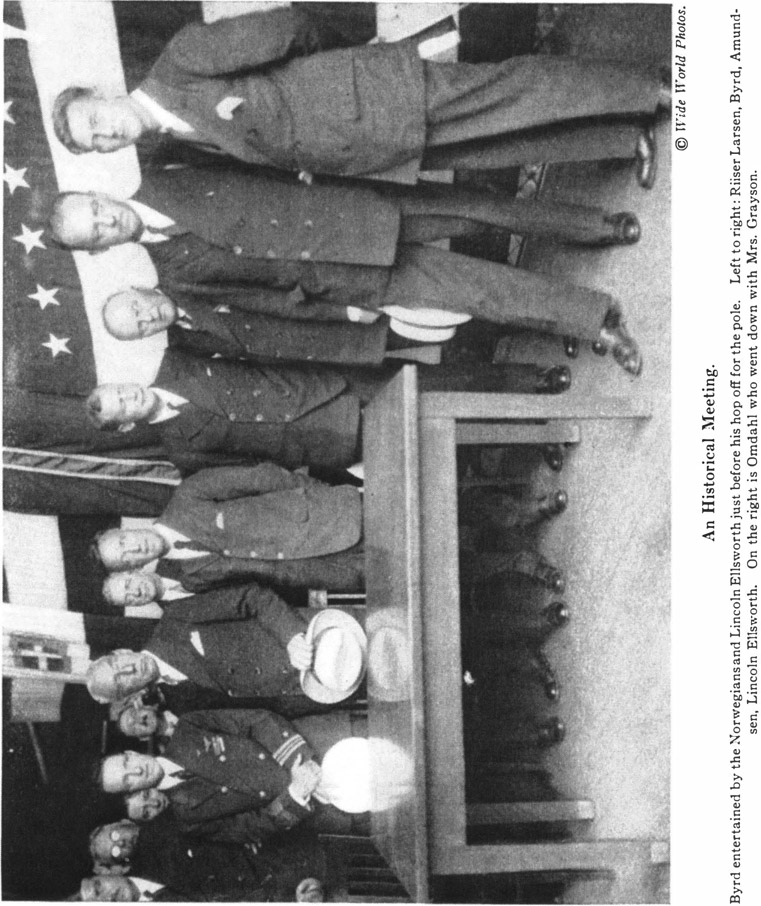

This fund raising goes on generally until the day of departure, for the explorer nearly always leaves with a deficit facing him. When I left on our North Pole expedition I had a deficit of nearly $30,000, which, before our expedition was disorganized swelled to nearly $40,000. The Amundsen-Ells-worth-Nobile expedition had a much larger deficit after the flight of the Norge.

Peary returned from his first expedition with a deficit. To pay off his debts he went on a lecture tour, giving 168 lectures in 96 days, and had enough funds left over to help finance his next expedition. Peary told some of his friends that he had never made a trip that was harder on him than this one.

When our North Pole sailing day finally came the expedition was only partially built by the dollars that had passed through my bank account from the hands of generous friends. For instance, we had procured the 3,500-ton steamer Chantier for the charter price of one dollar a year so long as we should need her. That we owe to the United States Shipping board. Armour & Company gave us meat. The Pioneer Instrument Company gave us instruments and experts. The Weather Bureau sent along William Haines, one of its most experienced meteorologists. Johns Hopkins University loaned us Dr. Daniel O’Brien, as agreeable as he was able. The Wright Aeronautical Company donated Doc Kincaid, noted last summer for having nursed the engines of all three planes that succeeded in flying the Atlantic. The Vacuum Oil Company donated oil; and the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, gasoline. Of the fifty-one men on the ship, I paid only five their accustomed salaries. This shows in some measure the untrammeled eagerness behind such a venture.

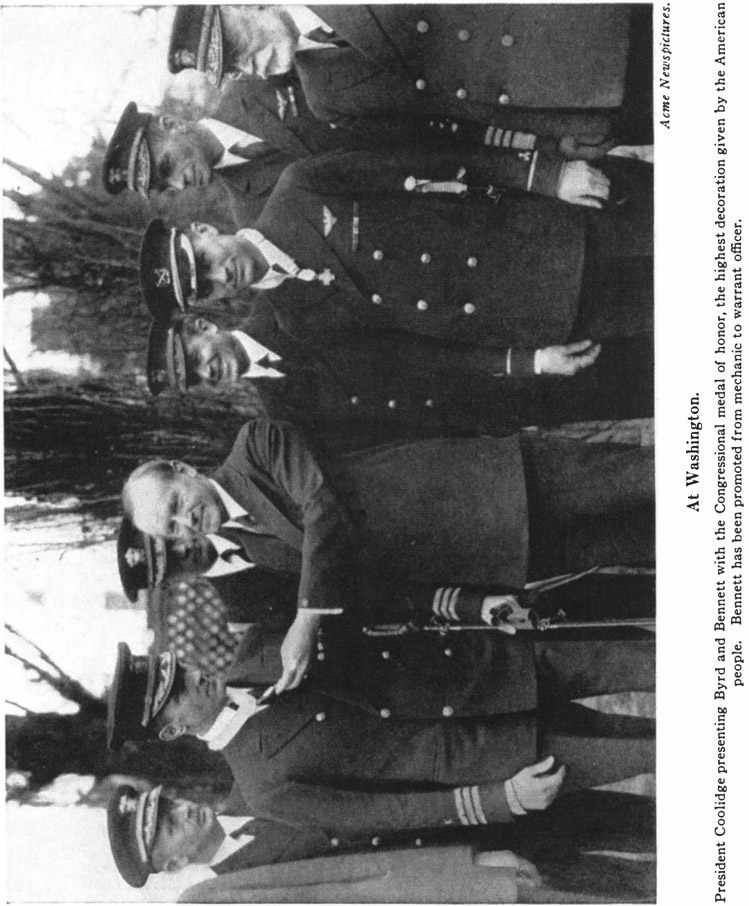

Indeed, the success of my North Pole expedition was due far more to the patriotism, unselfishness and loyalty of a great many people than to any peculiar competence on the part of Bennett and me, who simply had the divine privilege of riding the winning horse. A dozen times the half hundred volunteers with me, by super-human effort up in the bitter weather of the Arctic, saved the day for Bennett and me. I believe this wide diffusion of indispensable support is one of the chief peculiarities of a modern expedition.

Few people seem to realize that one in my position has to support his family in between times. His mail is mountainous, yet he must bear the secretarial expense of handling it. And he is considered “high-hat" if he does not answer promptly and satisfactorily everything from a demand for an autograph to an application for membership in his next expedition, both of which come in daily by the hundred. Telegrams become a prodigious item of expense as time passes.

Then there is the so-called public service which the hard-working explorer is called upon to shoulder. This includes being present at innumerable ceremonies, many of which have not the remotest connection with him or his work; charities, conventions, civic drives, political shindigs and scores of other kinds of log-rolling.

At all times he is being called upon to use his nicest judgment about accepting business offers. One offer would have given me $5,000 a week to talk at a string of moving picture theatres for fifteen minutes every time my polar picture was shown. Some of my enterprising friends urged me to send our North Pole plane around the country, taking up passengers at ten dollars a head. Since we could have held ten at a time, that meant a profit of almost $100 every ten minutes, or close to $10,000 a day. That was most tempting, but had we done that we would have been commercializing our expedition in such a way that we would have defeated one of our main purposes, which was to help aviation. Instead, we chose to arrange with the Department of Commerce and the Guggenheim Fund for a tour around the country on behalf of aviation. Bennett piloted the plane successfully to forty-four cities. Bennett’s batting average was high, not missing a single engagement on his list. I talked on aviation in more than fifty cities. Had we commercialized the expedition instead of doing this, we would not have been worthy of support.

I find it a toss-up as to whether the explorer has a harder time with his complications before or after an expedition. It is a heavy strain to get ready; but the aftermath of a successful trip is in some ways worse. Crossing the Polar Sea and the Atlantic were fatiguing flights. Yet both times I had to get busy the moment I landed and write long articles for syndicates that had bought my story of the flights. When civilization is reached there springs up an unavoidable round of social engagements. At such periods only the hours between midnight and three A.M. are available for answering wires and cables, drafting instructions to personnel, making important decisions of policy, considering invitations and attending to innumerable other items of business. I have averaged only three or four hours of sleep a night after both my polar and Atlantic flights, despite the fact that I have never felt so much the need of rest as I did at those times.

The legacy of troubles bred in days like these is a long one. I am still receiving bills which came out of the confusion of our North Pole flight.

“Of course a reporter wrote your story, didn’t he?” so many people say to me.

Frankly I don’t believe in having some one else write one’s statements to the newspapers. Occasionally it can’t be helped. After our landing at Ver-sur-Mer, when I had had a total of only about two hours’ sleep over three days and three nights, I found myself under contract to produce copy for the papers. Pure physical exhaustion and an official delegation from Paris led me to dictate my first instalment to a journalist. I did not see his version until I returned on the Leviathan. It was well done and, in the main, true. But had I written it myself I should not have repeatedly declared, as the reporter did, during my flight that I was completely lost. We weren’t. While over the ocean, three hours before we reached France, we knew our position and course very exactly. When we found Paris smothered in fog we were able to navigate back to the coast, the only place we could make a safe landing and save our lives. A small point in the layman’s mind, but a vital one in the aeronautical record.

Yet an explorer must live up to his press contracts or forfeit his profit, the life blood of his expedition.

Lecturing is a vastly overrated way of raising money for explorations. It is the most trying work I know. With its one-night stands, receptions, banquets, irregular hours, disordered regime, long periods of standing and general nervous strain, it can well break the strongest man in a few months. In addition to all this, the active explorer is generally carrying on much correspondence in connection with the preparation for his next expedition.

The order of the lecturer’s day is fairly similar in each city. Usually he is met by a delegation of friendly citizens. Luncheon that is really a daylight banquet follows. There are speeches of welcome, culminating in an address by the distinguished visitor. Sights of the city come next—a vague method of pseudo entertainment that may mean anything from a series of cocktail parties to a hundred-mile motor trip over the local parkways. Often there is an afternoon reception, engineered by the ladies. Then the big banquet and lecture of the evening. The explorer is lucky if he gets back to his hotel by midnight and is free to plunge into the pile of telegrams, letters and long-distance telephone calls awaiting him.

My attitude may seem captious and ungrateful. But I am only trying to give a dispassionate picture of what men in my position go through. In fact I find that, when fully aroused, the generosity and hospitality, the civic pride and the innate kindness of the average American city transcend those of any race or nation in the world. I have felt humble and grateful for the wonderful kindness and hospitality I have received.

I wish I had space and words to emphasize more strongly the priceless experience I have had in the incredibly warm friendliness I have met everywhere. I would’nt take anything for that experience. I can only say that I do not accept this tribute for myself alone but also for the fine young Americans who have helped me to succeed.

Just when the explorer is trying his best to be a hardboiled business man and get the threads of his mountainous debts unraveled, he often finds himself tangled up in an altogether new set of complications which I believe the average business man is rarely called upon to face. I mean personalities—personalities of men and of women; of men and women who write letters ; of men and women who want to give money; of men and women who compose audiences, and so on.

For example, each audience has its own personality. One of the warmest I ever faced was that collected by the Junior League in a conservative northern city. One of my coldest was far south of the Mason and Dixon Line. I am a Southerner, too. One audience will have little sense of humor, another a lot. Some are serious and detached, others are gay and responsive. The speaker must guard against succumbing to the mass mood of those who face him.

School children are irresistibly enthusiastic. Thousands of my letters are from boys and girls in their teens.

In this connection it is significant that girls outnumbered the boys ten to one in asking to go on my Arctic flight, whereas applications for the South Pole come in now at a rate of 100 boys to one girl. Looks as if the girls want to keep warm—or else get to Paris—doesn’t it?

Probably the most personal, surely the most insistent thing that keeps cropping up through all the explorer’s business, through all his lecturing and writing, amid all his money gathering and on all his travels, is a question. Strange to say, this question is unanswerable. No, let me modify that: it is not satisfactorily answerable to the average person. This question is:

What is the sense of Arctic exploration anyway?

And the more the questioner knows about this question, the harder it is to answer. But let me frame my own reply:

The Antarctic continent, our next destination, is save on a tiny fringe at one or two spots where seals and penguins abound, this white wilderness is, so far as we know, lifeless as space and nearly as cold.

It does at first sight seem unreasonable to spend large sums of money and face great hazards in order to know more about so uninviting a part of the world. The only thing its exploration can promise is a tithe of abstract scientific information, though our expedition will be purely a scientific one.

What then is the good of adding to man’s store of abstract knowledge?

The answer to this must come ultimately in material results, if at all. For example, as a result of centuries of apparently aimless research we now have the telephone, the telegraph, radio, airplanes, anæsthesia, antitoxin, illuminating gas, electric lights, X-rays, automobiles, and a thousand other devices that make life safer and happier. Every one came suddenly and seemed to be the work of an inspired inventor. But that was not true. Each was the culmination of generations of plodding abstract inquiry into the unknown, and more often than not the inquirer was jeered or feared for being a necromancer.

Exploration is just such inquiry after abstract knowledge. We anticipate no immediate gain, unless it is from our meteorological investigations, no application of our discoveries to commerce. The expedition’s scientists can perhaps only unfold something of the past. For my South Polar trip our justifiable incentive is that we shall add to man’s store of knowledge in the abstract if only by gazing upon and photographing a portion of the 4,000,000 square miles of Antarctic territory as yet unseen by human eye.