CHAPTER 11

Organising information

There is a brilliant child locked inside every student.

Think of your child’s mind as if it were a wardrobe. Most people have things scattered all over the place. The socks are jumbled up with the shirts and the coat that should hang on the hook has gone missing. Ideas and knowledge can get jumbled in much the same way.

Geniuses don’t waste time. They organise what they know so that it can be retrieved when needed, linked to other things where possible and used regularly.

We live in an age of infoglut. Most people are swamped with information and become overwhelmed. The Rex part of the brain – the part that really doesn’t want to work too hard and just wants to get back to resting and surviving – becomes distracted or irritated. This turns bright kids into passive recipients rather than producers of knowledge.

The way we organise information inside our heads affects our ability to focus, store and retrieve knowledge. It also influences our creativity – you can’t link ideas in new ways if you can’t access them easily.

In a cluttered and frenetic world where a thousand things clamour for our attention, we need to help our children and ourselves become discerning recipients of information.

Fill your mind with inspirational thoughts and it will amaze you. Fill your mind with junk and guess what you get? This means trying to expose your child to the very best ideas, books, movies, pieces of music and activities.

Ten ways to declutter your child’s mind

- Have a day a week when you minimise your whole family’s exposure to electronic media.

- Have at least one family meal (many more if you can) without electronic distractions.

- Use your router or airport system to prevent access to the internet after a set hour each night.

- Firmly discourage checking social media sites during conversations. When you are with people be with them. Practise being present.

- Try to have conversations about ideas as well as events. Rather than always asking children how their day was, ask them what their big idea or thought of the day was.

- Know that news services take a proctological view of life. They report the most sensational and negative stories. Be wary of watching the news: some children find it distressing and become preoccupied with it.

- Avoid commercial advertising wherever possible.

- Know that anxiety can cause children to think in repetitive loops where they ruminate. Talk with them about the options and use the decision-making model PICCA (see Chapter 7) to lead them towards action.

- Do activities with your children that require them to be in the moment. For example, it is difficult to catch a ball, shoot for goal, juggle, surf or ski if you are thinking about other things.

- If you have read a story or seen a film, have conversations about what they think was the main idea or most important message.

Help children learn things in the way they will most likely use them

If I asked you to tell me the months of the year, you would list them fairly easily. If, however, I asked you to tell me the months of the year in alphabetical order you might struggle a bit more.

The point here is to teach your child in precisely the same way that you want them to use the information. If you want them to pack their lunch for school, you might want them to remember to put the ingredients into their lunch box in the order they will eat them. For example, snack for break, sandwiches for lunch, fruit, a drink.

Ladders of understanding and the art of backwards learning

One of the best ways to learn something new is to learn it backwards. Backwards learning uses ladders of understanding and is a very powerful way of organising knowledge. I suspect you already have used this process even if you’ve never heard of ladders of understanding because this is precisely the way most people learn to tie their shoelaces.

Do you remember how you learned this skill? It is probable that someone made two loops for you and asked you to tie them together. Once you could tie the loops, they then asked you to form one loop. Then the other loop. Eventually, you can complete the whole task by learning each step in backwards order.

Very cleverly the person teaching you gave you a sense of mastery (tying your own shoelaces) before teaching the steps you needed to be able to get that sense of mastery.

This is also why children often learn to brush or dry the dog after a bath before being given the task of washing the dog.

The application of ladders of understanding goes well beyond tying shoelaces and washing dogs. The same method can be used to help children learn procedures, processes and ways to solve problems.

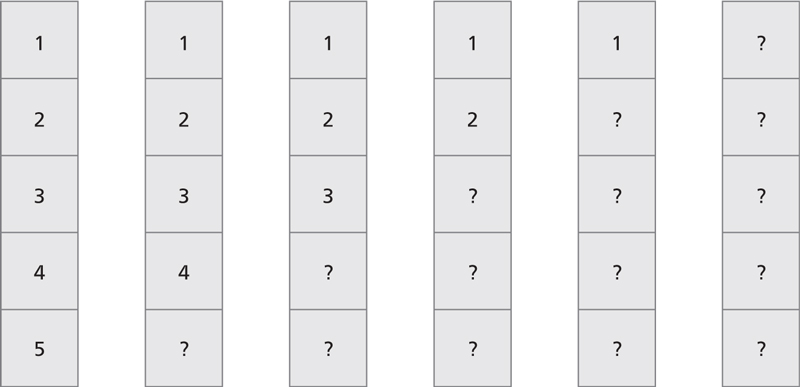

For example, let’s say I have a five-step procedure such as solving a maths problem or completing an essay. We might outline the steps involved as follows.

Then we might develop a similar five-step procedure and outline the first four steps and ask the child to complete the fifth.

This then continues with several parallel problems.

As you can see, the child is given all five steps at first and then in a parallel example the first four and they have to work out the last step, then the first three, then the last two and so on.

Ladders of understanding help children to see there are sequences in activities like writing a good essay, learning to play a musical piece, completing a scientific experiment or solving a maths problem.

Outlining the steps involved in solving a problem also helps children develop self-explanations where they can think to themselves, ‘First I’ve got to do this and then I’ve got to …’

Children who can think through and explain to themselves the steps involved in solving a problem get better results at school, especially in science subjects.

Ladders of understanding outline problems using the same structure, helping children to increase their pattern recognition. Children begin to see that some types of problems are asking you to solve the same issue expressed in different ways. For example:

Problem 1

I had five birds. Three flew away. How many are left?

5 − 3 = ?

Problem 2

I had some birds. Three flew away. I now have two. How many did I start with?

? − 3 = 2

Problem 3

I had five birds. Some flew away. I have two left. How many flew away?

5 − ? = 2

Problem 4

I had some birds and some flew away. I now have two left.

What number of birds might I have started with?

How many might have flown away?

How many different combinations can you find?

Is there a pattern?

Grouping and categorising

From an early age children can learn to group objects in different ways, such as shape, size, colour and texture. They can also learn to associate concepts with categories. For example, which of the following do we associate with winter: sunscreen, snow, frost, football, blossoms, hot days or fireplaces?

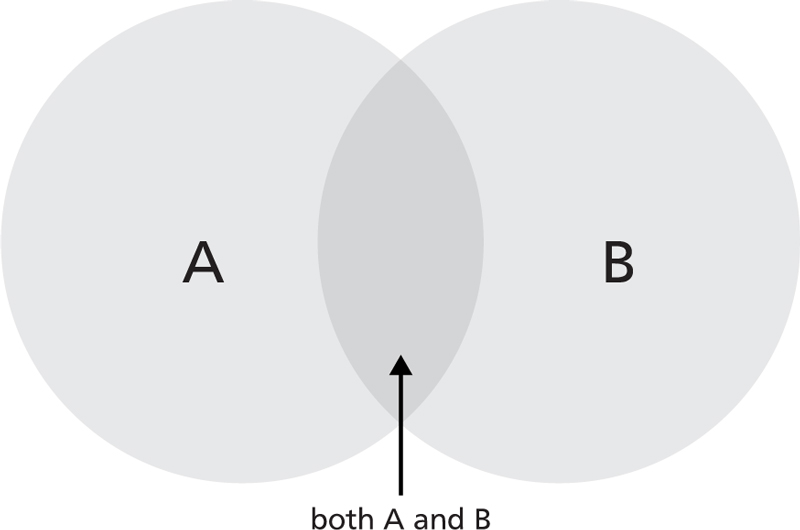

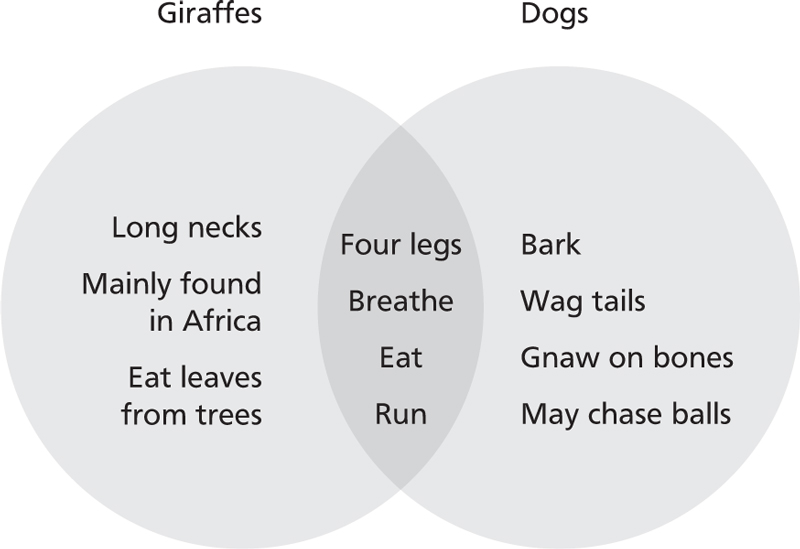

Once children have got the skills of associating concepts with a category, they can move to comparing two or more categories using Venn diagrams.

To help children learn about Venn diagrams, take two (or more) concepts and consider how they are different and how they overlap. For example, dogs and giraffes both have four legs, breathe, eat and run about, but only dogs bark, wag their tails and gnaw on bones and only giraffes have long necks and are mainly found in Africa.

The easiest way to illustrate this for children is to place some hoops on the ground then put ideas or pictures on pieces of paper and sort them into the different sections. You can then ask children to duplicate this Venn diagram they have made on paper, discussing it with you as they go.

Why this is so important for children to learn is because we know that identifying similarities and differences results in a 45 percentile point improvement in school marks.

How to make memorable notes

One of the best ways to organise information is to create notes. Most geniuses have intricate systems of filing, storing and organising information. Their system may look haphazard to the casual observer but it is there. Geniuses methodically and systematically capture good ideas related to their interests and organise them in ways that are useful to them.

From 2001 onwards with teachers from around the world, I conducted ‘practical intelligence projects’ looking for some of the more powerful ways to help children learn. The note system outlined here evolved from those discussions.

Essentially it is an adaptation of the Cornell method of note-making and involves children writing a heading for the topic at the top of the page and then dividing it into three main sections.

- In the largest one children write their main notes.

- In the sidebar they write the most important bits of information or the key ideas.

- At the bottom they convert the same knowledge into a visual. A Venn diagram is ideal but a bubble or concept map can also work.

With younger children, it can be useful if you take them through developing a set of notes on a book they have read. Playing games such as identifying the main point of a film, story or TV show helps children learn to pick out the key ideas.

In an overloaded, distracted world, a person who knows how to focus on the most important piece of information, pick out the key idea, and identify the crux of something is at a major advantage.

By using this note-making system, they have transformed the same bit of knowledge into three different formats: main notes, key idea and a visual representation, and increased the retention of that knowledge.

The problem is it takes human beings 24 repetitions of anything to get to 80 per cent of competence. How do you get kids to repeat anything 24 times? Next I’ll show you how to give their memory a hand.

Giving memory a hand – a repetition method

Once children have learned something, ask them to summarise it by making a summary hand.

Have them cut out cardboard shapes of their hand. (Very young children may need you to cut it out for them.) Then ask children to give their memory a hand.

On one side of the cardboard hand they write the five most important pieces of knowledge about a topic – one on each finger or thumb. Some examples might be:

Five features of autumn: changing leaves, temperature drop, rain, cooling soil, shorter days.

Five phases of art history: renaissance, neoclassicism, romanticism, modern, contemporary.

Five types of chemical reactions: combustion, synthesis, decomposition, acid-based, single and double displacement.

In the palm area they either draw a Venn diagram or write a more detailed summary of the topic in point form.

They then turn their summary hand over and write:

- their name

- two questions that they can use to test their memory of the topic

- one question that is really tricky.

They then assign a point value to the tricky question.

Be patient! It will take children time to develop the skill of making a good summary hand to organise information. Ideally you will help them to learn this skill over several years.

This method has been used successfully with children of all ages, substantially decreasing the number of repetitions children need to understand key concepts. It helps secondary school students organise and revise main ideas and prepare for exams. It helps younger kids organise their thoughts.

Every so often, have children test their memory and knowledge by trying to answer the questions before turning over the hand to check the answer.

I choose a block of marble and chop off whatever I don’t need.

Help children develop notes with flair and memorability

Teaching children ways to take down and organise the information they learn provides a powerful way of increasing their memory.

The last thing kids want is a set of boring notes. So help them to develop colourful notes with attention-grabbing elements.

Use varying sizes so that some words STAND OUT!

Some children become anxious at school and want to write everything down. Teach them to use symbols and abbreviations.

| Teaching children organisation skills | |

|---|---|

| Ages 2–4 |

|

| Ages 5–7 |

|

| Ages 8–11 |

|

| Ages 12–18 |

|