The Grain Offering (2:1–16)

Grain offering (2:1). Throughout the ancient Near East, people frequently presented sacrifices consisting of grain, which was the staple human diet. While grain offerings could be independent (as in Lev. 2), they were often served with drinks as accompaniments to animal sacrifices (Num. 15), so that the deity received a well-rounded meal (cf. Gen. 18:6–8). Thus, on the fifth day of the Hittite Ninth-Year Festival of Telipinu, this god was to be offered choice meat portions (of 10 bovines and 200 sheep!), plus thick breads and drink offerings (see sidebar on Lev. 24).36

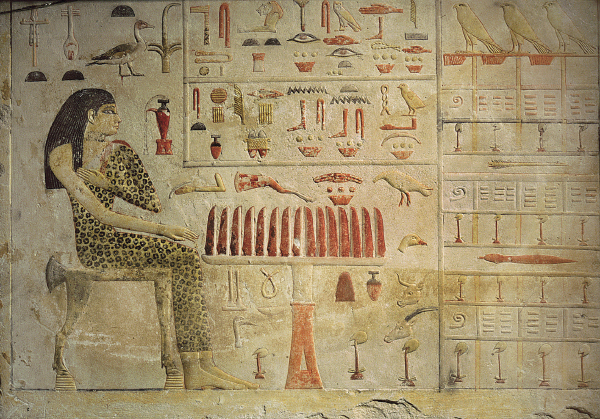

Grain offering on a stele of Princess Nefertiabt

Werner Forman Archive/The Louvre

Baked in an oven (2:4). Ancient Israelites ate grains, especially barley or wheat, in various states. However, Leviticus 2 limits grain offerings for the Lord’s altar to unleavened products of fine-quality wheat flour, that is, semolina. For more on this subject, see sidebar on “Ancient Grain-Processing and Bread-Making.”

You are not to burn any yeast or honey (2:11). Apparently the reason for excluding yeast from the altar was that leavening involves a kind of decay through fermentation, which was associated with mortality/impurity and thus had to be separated from intimate contact with God’s sphere of holiness and life. Along the same lines, honey (most likely of fruit; cf. 2 Chron. 31:5) was banned from the altar because of its susceptibility to fermentation (cf. Num. 6:3–4).37

Non-Israelite peoples, whose deities were not dissociated from death in the same way, frequently offered honey to their gods. Thus in Assyria and Anatolia, honey (along with other liquids, such as oil and wine) could be poured into a ritual hole in the ground as a libation for an underworld deity.38 The final ritual of the fifth day of the Babylonian New Year Festival of Spring was a burnt offering to celestial gods that included honey, along with ghee and oil.39

Salt of the covenant of your God (2:13). In antiquity, parties who shared salt (here the Lord and the Israelites) were united by mutual obligations. Thus, a letter from Neo-Babylonia refers to a tribe’s covenantal allies as those who “tasted the salt of the Jakin tribe.” Similarly, the Greeks salted their covenant meals, and in Ezra 4:14 those who tasted the salt of the Persian king’s palace were bound to loyalty to him (Ezra 4:14).40

Since human allies establishing a covenant would commonly share a meal featuring salted meat, it made sense for salt with Israelite sacrifices to serve as a reminder of the covenant between God and Israel. Because salt was employed as a preservative, its use in a covenant context also emphasized the expectation that the covenant would last for a long time, a meaning attached to salt in Babylonian, Persian, Arabic, and Greek covenant contexts. Because salt inhibits the leavening action of yeast, which represented rebellion, salt could additionally stand for that which prevented rebellion. A different reason for the appropriateness of salt in connection with covenant is found in its association with agricultural infertility: “In a Hittite treaty, the testator pronounces a curse: if the treaty is broken may he and his family and his lands, like salt that has no seed, likewise have no progeny.”41