Arrangement of the Tribal Camps (2:1–34)

Around the Tent of Meeting (2:2). See comment on 1:1.

Each man under his standard (2:2). Each tribal leader is to camp according to the standard that signifies his ancestral house, around and away from the tabernacle.20 The terms degel (“standard”) and ʾ ōtôt (“signs”) refer to some kind of banner or flag (see comment on 1:52). In the War Scroll from the Qumran caves, distinguishable standards were to be carried by each division within the ancestral tribe.21

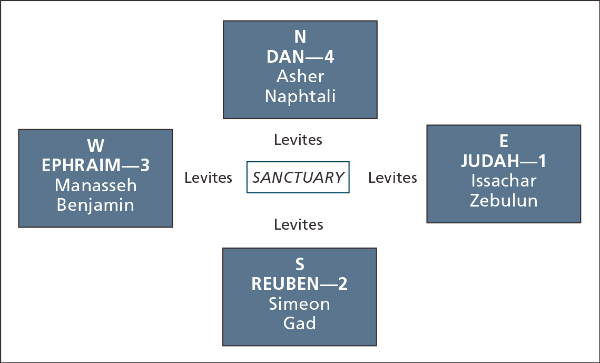

The tribal encampments and the order of their marching through the wilderness had a definite structure. See “The Tribal Encampments of Israel around the Tabernacle.”

The Tribal Encampments of Israel around the Tabernacle

Sacred Responsibilities of the Levites (3:1—4:49)

Family of Aaron and Moses (3:1). The genealogical record (Heb. tôlēdôt) of the family of Aaron and Moses stands firmly within the biblical and ancient Near Eastern tradition of recounting one’s ancestry in societal ritual. Genealogical records served several purposes: (1) to provide historical connection in the present in relationship to a pivotal point in the past, (2) to preserve familial community and organization within the larger societal structure, (3) to justify one’s present position by providing an historical precedent from one’s family line, or (4) to provide future generations with a source of pride and presence.22

Typically in the Bible genealogies link the present generation with the past and then describe the role of the present generation in the life of the religious community. In the Atraḫasis Epic (a version of the Babylonian flood account), the concluding statement of each of the three tablets functions like a modern title page with information about date of composition, authorship, and title. Like the genealogical statements of Genesis (e.g., Gen. 2:4; 5:1; 6:9; 10:1), Harrison suggests that Moses used his records of the census to “validate his authority and that of his brother, Aaron.”23

Nadab the firstborn (3:2). Normative in ancient Near Eastern law during the Bronze Ages and later were the rights of primogeniture, by which the eldest son received a double portion of the family inheritance. But he had certain responsibilities, such as care for the aged parents and their eventual proper burial, and maintaining ancestral worship.24 This pattern also ensured the orderly disposition of property from one generation to the next. If the firstborn died, as in the case of Nadab (and then Abihu), the responsibility went to the next living kin (Eleazar and then Ithamar).

Sometimes the rights of primogeniture were displaced by divine preference (e.g., the choice of David as king, 1 Sam. 16:1–13) or by negotiation (e.g., Jacob and Esau, Gen. 26:24–34). According to the Laws of Hammurabi, a father could choose the son of preference, as Jacob did in conferring the status on Judah instead of Reuben after the latter slept with Bilhah, his father’s concubine.25 Daughters could also sometimes inherit property, as in New Kingdom Egypt. Texts from Emar provide some of the closest examples to Israelite law on these issues.26

Put to death (3:10). The Levites served as guardians of the sanctuary, functioning as a lightning rod for the fiery wrath of God against potential encroachment on the sanctuary. Elsewhere human and divine guardians were positioned to prevent violation of the temples and cities. For example, gargoyles and various creatures in Egypt and Mesopotamia (symbols of divine entities) were positioned at the entrances to temples.27 Priests at Mari on the Euphrates and at the Hittite capital of Hattusas performed night-time guard duty, for which improper performance of duty was punishable by death.28

Gigantic Lamassu figures guarded the entryway to temples and palaces, threatening harm to trespassers.

Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia Commons, courtesy of the Louvre

Levites are mine (3:12–13). Rather than having individual clan rights of primogeniture for maintaining the sanctuary and ancestral worship, Israel has an entire tribe dedicated to proper worship of God. In the exodus event, the Lord commanded that every firstborn male of humans and animals be dedicated or sacrificed to the Lord as a sign of faithfulness (Ex. 13:1–16). The Levites became the substitute for the firstborn males of Israel.

Ancestral worship practices were common in ancient Near Eastern cultures. In Egypt the Book of the Dead emphasized the proper care and provision for the deceased. At Ugarit, mortuary ritual attended to deceased royal ancestors so that they might bring blessing to the current king.29 In Mesopotamian ritual the cult of the dead included practices whereby a “caretaker” made funerary offerings and poured out water libations while invoking the name of the deceased.30 Such practices became common in Israelite popular religion, but were condemned by the law and the prophets (Deut. 14:1–2; 18:10–11; 26:12–15; Isa. 19:3; Jer. 16:5–9).

The money for the redemption (3:48). On the issue of redemption money, see sidebar on “Redemption Money in the Ancient Near East.”

Hides of sea cows (4:6). This translation of taḥaš is unlikely since sea cows, porpoises, or dolphins are unclean animals (aquatic life with fins but not having scales and thus prohibited from consumption or other usage; see Lev. 11:9–12). According to Milgrom, taḥaš should be rendered “yellow-orange.”31

Cloth of solid blue (4:6). The “blue cloth” covering mentioned in verses 6–14 was actually bluish purple (tekēlet), and the “purple” (ʾargāmān; NIV “purple cloth”) refers to a reddish-purple dye (4:13). These dyes were produced from the various murex shells, with the Murex trunculus used in producing the bluish-purple dye, and the Murex brandaris and Thais haemastoma shells yielding the reddish-purple extract.32 The use of these shells along the shorelines of the Mediterranean basin is attested in archaeological surveys and excavations of sites dating to the early second millennium B.C., from Greece to Asia Minor in the north, and from Ugarit to Tyre in the east.33