The Book of Balaam (22:1—24:25)

Plains of Moab (22:1). This area is the broad plain between the Transjordanian highlands and the Jordan River, extending about ten miles from just north of the Dead Sea. From this locale the campaign into the promised land of Canaan will be launched.

Upper Euphrates Region

Balak . . . king of Moab (22:2, 4). Unknown outside the Bible, Balak is called a “king of Moab,” meaning he was the titular head of an emerging tribal confederation (as were other groups in Transjordan, such as the Edomites and Ammonites). Territorial borders of these clans were not well defined until the Iron Ages, when classical Moab extended from the Wadi Zered border on the south with the Edomites to the Arnon River gorge on the north, and from the Dead Sea on the west to the desert on the east. At various times Moabite domain reached north to Heshbon and the surrounding plains.

Elders of Midian (22:4). The Midianites have their origins in northern Arabia and southern Transjordan; they were descendants of Abraham and Keturah (Gen. 25:1–6). Their loose-knit, seminomadic culture carried them from Arabia to Sinai and Egypt (Ex. 2:15–22; Num. 10:29); occasionally they made forays into Canaan as traders (Gen. 37:25–36) and as invaders (Judg. 6:1–6). In this narrative a group of Midianite elders (note, no king is cited) joins the emissaries from Balak in enlisting the services of Balaam to curse Israel. Later the alliance with Moab is reflected in the idolatrous incident at Baal Peor (Num. 25). For these two affairs they are condemned and suffer the consequences in the Midianite reprisal campaign (Num. 31).

Pethor, near the River (22:5). Pethor is likely Pitru, situated thirteen miles south of Carchemish on the Sajur River tributary west of the Euphrates. Pitru is cited in the annals of Shalmaneser III (859–824 B.C.), and earlier a Pedru is mentioned in the annals of Thutmose III (ca. 1467 B.C.).220 The phrase translated in the NIV “in his native land” is probably better rendered “in the land of Amaw,” a region west of the Euphrates possibly mentioned in Egyptian and Mari inscriptions.221 The distance from Pethor to Moab exceeded four hundred miles, making each leg of the journey by the emissaries and Balaam a twenty- to twenty-five-day trek.

Curse (22:6). Ancient Near Eastern texts recount the power of diviners, magicians, and sorcerers to discern, intervene, and even manipulate the will of the gods through augury, special sacrificial rituals such as extispicy (ritual dissection of a liver or entrails), and incantations aimed at blessing or cursing an individual or group, forecasting the future, and advising kings and other leaders.222

The reading of omens through observing various aspects of nature was considered a skilled science. Glossaries of omens and detailed lists of animals and objects and their potential use in divination are found among the texts of the Hittites, Babylonian, Assyrian, Egyptian, and other cultures. Knowledge of the ways, workings, and occasional whims of the divine and the skill of cajoling these deities into bringing beneficial or detrimental results was a highly prized craft. A parallel to the Hebrew concept of curse (ʿ ārar) is found in the following Akkadian text:

May the great gods of heaven and the nether world curse him (li-ru-ru),

his descendants, his land, his soldiers, his people, and his army with a

baneful curse; may Enlil with his unalterable utterance curse him

with these curses so that they speedily affect him.223

Fee for divination (22:7). This phrase describes the men “carrying divination in their hands” (ûqsāmîm beyādām), which various scholars have translated as a divination fee, divination equipment, or an idiom describing the emissaries of Balak as men “versed in divination.”224 Hurowitz, developing the lead of J.-M. Durand, delineates several parallel contexts from Mari in which objects used in the process of divination were presented, dispatched, and used in the negotiation with the recipient of the divination. These included such items as clay models of intestinal entrails, livers, or other parts used in the practice of extispicy, the art of ritual dissection. Hurowitz concludes: “If Balaam was, among his various magico-religious talents, a bārū, and if extispicy was practiced in Moab as it was at Canaanite Hazor and Megiddo and Ugarit, then the qesāmîm referred to may well have been baked clay models of the entrails predicting Moab’s downfall and Israel’s ascendancy.”225 Fear of the Israelites may have so alarmed Balak’s own trained diviners that they sought a person of great renown as Balaam, who might exercise his expertise in allaying Moab’s potential destruction by cursing Israel.

Opened the donkey’s mouth (22:28). Three times Balaam’s female donkey observes the angel of the Lord in a manner more perceptive than that of the renowned seer of the gods. The vineyard scene indicates that the theophany took place in the arable highlands of Transjordan, probably between Damascus and Rabbath Ammon. Piles of stones gathered from the area for planting were used to create boundaries between neighboring vineyards.

Tales of talking animals in the ancient world often contain warning, irony, or satire. In the Egyptian Story of Two Brothers, a cow advises one of the brothers to flee because his brother was seeking to kill him with a lance.226 From the Aramaic Words of Ahiqar (seventh century B.C.) comes a conversation between a lion, a leopard, a bear, and a goat, each representing a human characteristic in facing the struggles of life before the gods.227

Interpretation of this donkey event has given rise to two general options: (1) God gave the female the power of speech similar to how he empowered Ezekiel to speak after a prolonged period of silence (Ezek. 3:27; 33:22); (2) the donkey’s normal braying was heightened such that it was perceived and interpreted by Balaam in a human manner.228 The scene is replete with irony in that the female donkey is more perceptive of God and is able to speak God’s word in a manner superior to the internationally renowned expert. Balaam is reminded he will only be allowed to speak what Yahweh, God of Israel, permits him to speak.

Kiriath Huzoth (22:39). The “city of plazas” (as the name translates) may have been a central market area for Moab. Biran, the excavator of Tel Dan in northern Israel, has noted a series of official buildings in the market plaza outside the gate of the Iron Age city that seem to have served as offices for oversight of commercial activity.229

Dan Iron Age gate complex where remains of a market plaza were excavated

Todd Bolen/www.BiblePlaces.com

Bamoth Baal (22:41). See comment on 21:18. Balak apparently thinks that Yahweh, God of Israel, might be more apt to be manipulated from a cultic center dedicated to a primary deity of the region (Baal, the champion of creation in the mythology of Ugarit). Bamoth (see comment on 21:17) is found in several compound names in the Old Testament, but does not occur as a topographical name anywhere but in Moab.230

Seven altars (23:1). Multiple altars are not attested elsewhere in the Old Testament, though the number seven denotes completeness or fulfillment. The importance of the number seven is reflected in the days of creation, the sanctity of the Sabbath, the sprinkling of the blood of the sin offerings on Yom Kippur, and the series of sevens in Revelation. A parallel use of seven is found in a Babylonian text in which a worshiper is instructed to “erect seven altars before Ea, Shamash, and Marduk, to set up seven censers of cypress, and then pour out [as a libation offering] the blood of seven sheep.”231

A bull and a ram (23:2). In ancient Near Eastern culture, the bull and ram were the most prized of animals and the obligatory sacrifices for persons from the upper echelon of society. The bull was the required offering of the high priest (Lev. 4:3–8) and the ram for a guilt offering (5:14—6:6). These animals are also a regular part of special offerings in the Canaanite-type culture at Ugarit in the mid-second millennium.232 For a divination context, this is a large offering reflecting the importance of the situation—a king acting on behalf of his people in an international crisis. Usually a sacrifice performed in connection with divination was just one animal whose entrails were then examined for an answer.233 Here Balaam offers the sacrifices in order to try to induce Yahweh to deliver prophecy through him.

Stay here beside your offering (23:3). Here the king himself acts on behalf of the Moabite people, performing a priestly role not uncommon among Northwest Semitic people.

Field of Zophim on the top of Pisgah (23:14). The field of Zophim (“field of the watchmen”) was probably named so because of its strategic observation location. Several scholars interpret this location as a known place for observing heavenly omens and making astrological observations.234 The Phoenicians referred to an astrologer as a tsope šamem (“watcher of the skies”). Balaam may have sought to observe the omen of bird movements at Zophim according to the common practice of augury known in Mesopotamia and in the Deir ʿAlla texts (ll. 7–9). Pisgah (cf. 21:18–20) is one of the prominent mountain peaks in the Abarim Range just northeast of the Dead Sea. There Moses will commission Joshua (Num. 27:12–23), and later God provides Moses an overview of the Promised Land (Deut. 34:1–12).

Change his mind (23:19). Unlike the gods of Mesopotamia, who were often whimsical and malleable, Israel’s God was unchangeable and therefore of incomparable integrity. Note the incantation from the Namburbi Texts of Mesopotamia: “The evil of the lizard which fell upon me, the portent of the evil that I saw—Ea, Shamash, and Marduk turn it into a portent of good, an oracle of good for me.”235 This incantation shows that the gods were believed capable of exploiting the ambiguity of omens to their pleasure. Ishtar, a principal Mesopotamian goddess, is known for possessing paradoxical, and at times mutually exclusive, traits.236

In this text “changes” denotes making idle or deceptive promises or failing to follow through on one’s words. In other words, it concerns integrity. Though the gods of the ancient world sometimes changed their posture on certain issues and even evidenced a change in character, they could normally be taken at their word (though sometimes their words were intentionally ambiguous and thus could mislead).237

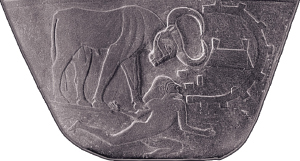

Wild ox (23:22). Israel’s strength was totally in her God; by his power she is compared to a ravaging wild ox. Hammurabi of Babylon declared himself to be like “the fiery wild ox who gores the foe.”238 Ancient Near Eastern deities were often depicted as horned bulls or as humans with the head and/or horns of the bull.239 Baal is depicted as wearing the horns of a bull or wild ox in a bas relief from Ugarit.240

Obverse of the Narmer Palette portraying wild ox

Werner Forman Archive/The Egyptian Museum, Cairo

No sorcery against Jacob (23:23). Israel did not need augurs, sorcerers, diviners, or magicians; in fact these were condemned. Augury included reading cloud patterns, bird movements, and other activities in the skies (see comment on 22:6). No such activity was the source of Israel’s defense, nor could such powers be effectively used against her. God would use a pagan diviner to communicate divine revelation for the purpose of blessing those whom Balaam had been expected to condemn.

Top of Peor (23:28). Peor is another of the peaks in the Abarim Range near Pisgah (see comment on 23:14), near the cultic site of Baal Peor, where some Israelites entered into idolatrous activity at the instigation of Balak and Balaam (25:1–19; 31:16). The site afforded a view to the north-northwest of the area of Jeshimon (“wasteland”—cf. Beth Jeshimoth in 33:49) on the southern end of the Plains of Moab near the Dead Sea.

Agag (24:7). King Agag ruled the Amalekites at the time of King Saul (1 Sam. 15:8). The Amalekites were Israel’s greatest enemy in the time of Moses, routed by Israel soon after the Exodus (Ex. 17:8–16); they defeated Israel after she rejected the gift of the land (Num. 14:43–45). Agag seems to have been a dynastic name among the Amalekites, and this oracle depicts a future victory in the exaltation of Israel.

Balak . . . struck his hands together (24:10). Fierce clapping of the hands was a sign of derision or defiance when used with this particular verb (Job 27:23; 34:37; Lam. 2:15).241 The same meaning is evident in Esarhaddon’s Prism Inscription, where the gesture accompanies mourning in response to what he calls the wicked behavior of his father.242

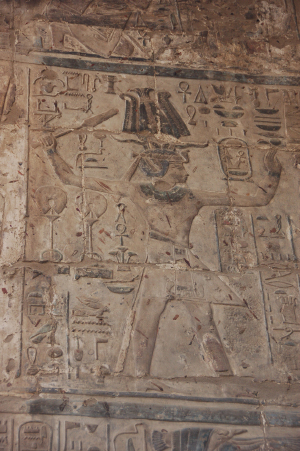

Star . . . scepter (24:17). It is difficult to document the star used as a symbol or metaphor for kingship in ancient Near Eastern literature. In later literature, this passage served as a basis for the star used on the coinage of Alexander Janneus (103–76 B.C.) to elevate the status of his kingship.243 Rabbi Akiba in the second century A.D. proclaimed Simon bar Kosiba to be Bar Kochba (“son of the star”), thereby claiming fulfillment of this messianic passage. The “scepter” symbolized royal power in both heavenly and earthly realms, as seen in royal monuments of the ancient Near East in iconographic and epigraphic forms. Thutmose III subdues his captives with his scepter in a relief from the temple of Amon at Karnak.244

Pharaoh striking with scepter

Frederick J. Mabie

Kenites (24:21–22). The Kenites were a nomadic clan living in the eastern Sinai region, whose roots are traced biblically to the descendants of Cain and are associated with metallurgical craftsmanship (Gen. 4:17–24). In Judges 1:16 the association is made between the Kenites and Moses’ in-laws (the Midianites Jethro, Reuel, and Hobab), the descendants of whom settled in the Negev near Arad. Later Kenites are found living as far north as the territory of Naphtali (cf. Ex. 2:11—3:1; 18:1–5; Num. 10:29–32; Judg. 4:17; 5:24–27). The present text notes a group of Kenites who, like some Midianites, become enemies of Israel and are eventually subdued.245

Asshur (24:24). This probably refers not to the later Assyrian empire of the ninth to seventh centuries B.C., or even the Middle Assyrian peoples of the Late Bronze Age, who seldom ventured west of the Euphrates. Rather, this citation denotes the relatively unknown Asshurites, a nomadic group of the Negev region mentioned in Genesis 25:3, 18 and Psalm 83:8. They were descendants of Abraham and his concubine Keturah.

Kittim (24:24). Kittim is one of the ancient terms for Cyprus (Gen. 10:4), derived from its major city Kition (thus Kitionites). In several Old Testament passages the term is used generically for the islands of the Mediterranean and their inhabitants (Jer. 2:10; Dan. 11:30). The Kittiyim mentioned in the Arad inscriptions are probably Greek and Cypriot mercenaries serving in the Judean army in border fortresses.246 During the Hellenistic age Kittim became a byword for the archenemies of God, a prominent motif in the Qumran scrolls in reference to the Greeks and then the Romans.

Eber (24:24). Eber occurs in the genealogy of Shem, from whom the Hebrews descended (cf. Gen. 10:21; 11:14–17); this offers no solution here since God will then be fighting against his own people. Eber perhaps can be associated with the Mesopotamian king Ibrim known from the Ebla Tablets of northern Syria of the third millennium B.C., but this reference antedates our context by more than a thousand years.