![]()

CHAPTER 27

Next stop, hardly a pinprick on a global map, was the low-lying Tuamotus Islands.

Outward bound from the tip of Nuka Hiva, Kyle scored a great game fish, a wahoo, whose weight we guessed at fifty pounds. Thumping it fatally on the head with our aluminum fish bat, we filleted the handsome fish, enjoying tasty sweet white fish meat for multiple delicious dinners and probably a few lunches to boot. Life was good again!

The word Tuamotus means distant in native Polynesian lore. Sailors know these as the dangerous islands. Scattered throughout the Pacific in an area as big as Western Europe, these islands, though not intended, became the final destination of the Norwegian adventurer, Thor Heyerdahl, and his raft Kon-Tiki. Some outer fringe islands were subject to French nuclear tests and are “off limits.” (Thank you, we didn’t want to go there anyway.) Others contain ancient sacrificial burial mounds from a forgotten civilization, and all atolls are part of the infamous Ring of Fire

Most Tuamotu islands in the five distinct archipelagos, were circular shaped and towered six feet above sea level—add maybe twenty feet if you climb a palm tree. The surface was mostly coral, and, where able to support plant life, we found surprisingly rich soil. We believed the fringing reefs were the remains of volcano rims that spurted and roared millions of years ago, and that the channel to the interior lagoon was where lava once flowed. Tidewater could rip through these narrow slits with dangerous intensity. The lagoons were sometimes deep, but usually neck-high shallow.

The difficulty for mariners approaching a Tuamotu atoll was being able to see the islands at all because they were so low. And, since not all mariners are vigilant, the fringing reefs are dotted with remains of wrecks—monuments to near-miss navigation.

Sailing was superb as we neared Manihi, our first landfall since leaving the Marquesas 470 nautical miles astern. Log entries included: “Close spinnaker reach. FUN!”—“Steady trades once again”—“Smoothest night since L.A.”—“Shooting stars fall like rain,” and—“Best sunrise ever.”

When we calculated ourselves inside twenty nautical miles of Manihi, we still couldn’t see it with our eyes or radar. Night was falling, so we slow sailed to avoid the coral responsible for aforementioned wrecks.

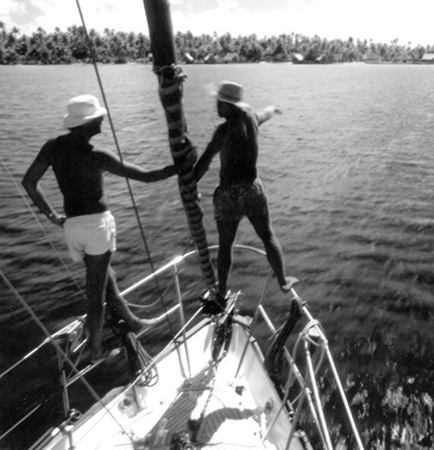

It was light by 0430. We stayed offshore until the sun was well over our shoulders. Tony then went up the mast in the bosun’s chair to the first spreaders, with Polaroid sunglasses, to guide us through the coral heads, as we cautiously approached the only channel through the reef. We missed slack tide. Coral formations, accurately named ‘bommies,’ lay just below the surface, and were capable of ripping a good-size hole in a moving vessel, such as us. Tony picked a path through the coral by shouting, “Bommie at 1:00 o’clock,”—“Large bommie at 12:00 o’clock”—“Sixty yards distant,” and so forth.

Greg and Kyle checking for bommies

An abundance of reef sharks, as many as ten in a minute, fascinated us—their sullen dark eyes patrolling the inlet. Equally fascinating were the native youth who, in the midst of the sharks, zipped past us on a fast inner tube ride, dashing out of the narrow channel.

“Ahhh,” sighed Tony, “this will be good on my board!”

To which Kyle went one up with, “No sissy board for me; I’m swimming naked with the sharks.”

Neither did either because we unknowingly dropped anchor close to a native shark pen, an underwater cage where sharks were lured into a chamber through a one-way opening, by placing baitfish inside. When the cage filled with sharks, and the baitfish had been devoured, the native fishermen harvested the sharks by gaffing the shark from above—while balancing themselves in rickety outrigger canoes.

We watched. Tony and Kyle, curiosity driving them, examined the cage by taking the inflatable around the perimeter. Their vivid descriptions of seven-and eight-foot frenzied sharks, attacking smaller ones in ferocious fight to the finish blood baths, depleted their boastful desire to swim with the beasts. Instead they went ashore, leaving “Pops” to enjoy the solace aboard Endymion.

I made a close inspection of the yacht. Cosmetically, she was showing early strains of multiple-person crews for extended periods. Varnish needed work, fabrics were soiled, and there was an assortment of scratches and dents, so-called battle scars from dropped items during sudden movements, something that should be expected.

I quit complaining to myself, and thought again how incredible this journey had been. Here we were, drifting and blending—anchored inside the rim of an extinct volcano. No waves, peaceful, warm sun, and not a bug in sight.

The boys returned, reporting a seawall a couple of miles away where we could tie alongside and resupply from Turipaoa, the island’s one small village. We moved over at dawn.

A group of islanders took us on tour. There was one beat-up video player on the island, no television or radio, and no phones. Natives with gaping holes where teeth once lived, or browned-out teeth from munching betel nut, smiled broadly without embarrassment. They’d never seen a football game, paid taxes, or heard of the Academy Awards, and were amazed, maybe even slightly frightened, by my Polaroid camera. What they did have was a twelve-foot-high skateboard ramp. “A damned good one,” according to Tony.

Close quarters at Turipaoa

Women performed pick and shovel labor to build walls and gardens, while the men folk fished—and, I believe, drank. A single generator powered the village until curfew at 9:00 pm.

Island fresh water comes from rain catchment systems built into buildings. I never saw a hose except for our ten-footer for the anchor wash-down system. Greg powered it up, showering unsuspecting children, who shouted with glee racing back and forth through it. Shortly every kid in the village was in line.

After a few days relaxing, we sailed to Rangiroa. Serious rain enabled us to fill our water tanks using our own catchment system, where rain runs down the mainsail, travels inside the Hood boom to a hose connected to the fill cap for our tanks.

Rangiroa is a larger island. The lagoon is over forty miles wide. All of the water in the two-foot tide rushes through two openings from the center. We timed our arrival and zipped into the lagoon on slack tide.

“Whoa! What’s this?” asked Kyle.

To our surprise, Kia ora, a classic small resort, appeared close by. Intrigued by the thatched roofs, long wooden dock stretching into the lagoon, and brilliantly white sand beaches, we chose to anchor in hopes we could take advantage of whatever they offered. It turned out to be a hamburger of questionable ingredients at $15.00 Pacific Francs.

In hurricanes, these islands can go completely under water with everything lost. In a 1983 storm one hundred and thirty souls disappeared forever, all from one small motu (island). They now have the island’s only solid structure, a hurricane center where, in a storm, the whole island will seek refuge with newlyweds ranked next to children in importance for survival. This motivated my crew to scout for potential brides in case of a storm.

Of the many wrecks on Rangiroa’s rugged coral, we found the wreckage of actor Sterling Hayden’s yacht Wanderer. It was aboard Wanderer that Mr. Hayden regained his sanity, after falsely being branded a communist by the McCarthy hearings in the 1950s. Those fiercely argued hearings also wrecked his movie career. He wrote a book about it called Wanderer, and it’s from that book we borrowed the christening poem for Endymion, that reads in part;

“Noble vessel built strong and true,

We have gathered here to christen you.

Brightly decked with flags so fine,

We entrust you now to nature’s brine.

May you avoid the sunken rock,

The hidden bar, with its sudden shock,

The iceberg vast, the fog so dense,

All dangers of the sea immense.

I can safely say, I am one of few ever to have seen the twisted remains of Wanderer, hard up on the coral, reduced almost beyond recognition by seas and storms. The sight was sad. I had always, in a vagabond’s sense, related to Sterling Hayden.

It amazed me how the christening poem so accurately described this voyaging and my moods, and my heart cried in silence for the man whose own adventure had ended here. In those emotional moments I felt the romantic kinship sailors feel for the life we live, be they rich, famous or ordinary people—drifting and blending.