![]()

CHAPTER 32

Raiatea-Tahaa – In a lifetime of sailing, I’ve never had such perfect, harmonious conditions, or enjoyed a sail as much as from Moorea to Raiatea. Once outside Tareau Pass, the ocean was crystal blue, a hue so rich it challenged the imagination. Light winds, no sea, and pleasant temperatures added to ideal sailing conditions. I snatched the beanbag from the aft deck, carried it forward, and sank into it, allowing myself to become one with everything beautiful on God’s big ocean. Again, I wished every person on earth could be where I was, even if for a moment.

It was still a good twelve hours to the spot we had picked to land on Tahaa. The starry night was again perfection. What surprised me was the amount of ocean traffic.

“Gotta be island supply boats,” remarked Tony, tending a luckless fishing line trailing us.

From the wheel, Denise commented, “They don’t look very safe.”

She was right. The supply ships were ants on the sea—low in the water with boxy cabins towering above the deck. Most were loaded beyond any conceivable legal parameter. All had generations of chattering people.

Tahaa and Raiatea is really one island, with a mountain at each end, connected by a reef and thin middle lowland. It is the largest of the “Leeward Islands” and closest in size to Bora Bora further to the west.

Throughout the day we, meaning Tony, caught a barracuda. They’re a lousy fish for eating. Tony somehow released them without suffering bites or gashes from their razor-sharp teeth. As the sun dipped out of sight, a lovely forty-six inch Wahoo decided to tempt fate, taking a chunk of our still trailing lure. Denise, with a passion for fishing, was on the rod and reel for this one. It was a battle. Denise won.

There could not have been a better ending to a South Seas day. Denise, taking salad duty, and Tony manning the deck BBQ in calm seas, created a fine fresh fruit and seafood meal. Neil Diamond serenaded us through our soft drink cocktail hour, and the Boston Pops Orchestra played the classics from deck speakers for our sit-down, cockpit-style dinner, served on the coveted backgammon table, covered with real linens, courtesy of Lady Denise.

It was a “be in love with life” evening. And we all knew it.

The night, aside from a myriad of stars, was dark, but not pitch dark like nights shrouded in clouds. With nightfall came the realization that the ‘ants of the sea’ vessel traffic was still out there, but few had navigation lights, if any lights. I recalled my Marine Corps training, learning how to determine rough distance in darkness from something as small as a glowing cigarette. People on the ant boats were smokers.

Denise, on her pre-midnight watch, said, “I’m watching a light 60 degrees off starboard bow. Can you see it?”

“Negative.” Tony tried to sound nautical.

“Something’s there; got to be a boat, and I can’t figure its course.” Denise sounded concerned.

Tony and I thought we could make out the shape of a small boat close by, on about the same course we were on and closely matching our speed. Tony checked the radar.

“He paints a reasonable radar picture; but then he should at half a mile from us. No problem!” he said to Denise.

“OK, but the smaller wooden boats all over the place, Tony? Can you see them?” Denise asked.

“It’s a problem. Some I see—some don’t show at all.”

“Damn radar,” said Denise

“Not really.” I got into it. “It’s the best Furuno makes today. We should be glad we have it. Soon we’ll have even better radar that shows the rain—and probably clouds.”

“I can’t wait,” Denise said sarcastically. She was listening to the ship’s clock chiming midnight and the end of her watch.

We kept an eye on the clunker boat Denise had warned of for another hour. It eventually pulled far enough ahead we no longer feared it.

Once, close to 0200, an out of tune diesel thumped by close at hand, forcing us to change course to avoid a collision with a bizarre-looking boat loaded with happy people. It also resembled a box-shaped boat, and we surmised the laughing people had no idea where they were, probably didn’t care, and wouldn’t care in the morning either. Just like all nights, we made it through this one. There was a lesson here, I believe, in vigilance. Our practice has always been, even on autopilot, to have someone at the wheel, hopefully alert and listening, because autopilot, for all of its virtues, does not have the collision avoidance warning system of human eyes or ears.

According to our charts, Tahaa offered two safe places to anchor. The one we chose required sailing around the island’s northern tip and then a slide south for a few nautical miles to a safe entrance into a lagoon reasonably protected by fringing reef.

We made our entrance almost precisely twenty-four hours after leaving Moorea. Several yachts bobbed at anchor. Ahead we saw a small town dock with a rusted hulk of a tramp supply ship lying aside and forgotten, and a white sandy beach, with a small sailing yacht firmly aground.

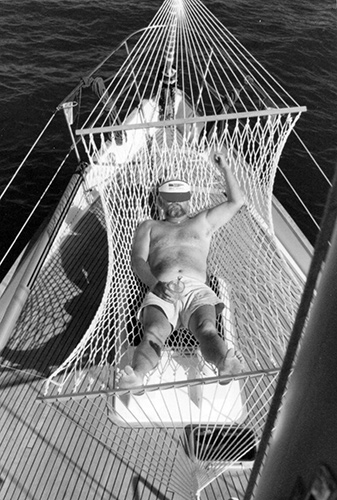

We anchored and did important things, like adjusting our sun awning, setting out the hammock, enjoying a tasty wahoo sandwich, and lowering the inflatable to explore ashore.

A couple in a small rowing dingy came alongside to welcome us ‘to paradise.’ First they warned us, “There’s two strange boats anchored at the far end. Castoffs. See em’?” inquired a bronzed heavyset lady of middle age, looking up from the dinghy. “Surely they’re druggies.”

“Ya think so?” Tony asked.

“Yeah. They’re skinny . . . and unsocial!”

Tony found that unfair. I found it a sign of the times that drugs were virtually in every niche of the globe.

Our welcoming lady also warned prices in stores were twice the average Papeete prices. The couple meant well, but didn’t come off well, more like busybody people we had left ashore long ago. A German man asleep, we were told, had stranded the boat we saw on the beach during an exceptionally high tide. The tide went out. The boat did not. It will be there until the next moon tide “unless he gets a change of attitude,” informed the lady.

Skip in our foredeck hammock

“Think I’ll go see if the druggies need some milk.” Tony was destined to visit the source of the woman’s scorn.

Going ashore, Denise and I experienced sticker shock. A tube of lip balm was over $10.00, a six-pack of warm canned soft drinks, with tinges of rust gaining a foothold on the rims cost $12.00, and my favorite mid-quality Chablis, a mere $23.00. All Pacific Francs. As expected, Chinese merchants, who came to the islands like locusts, controlled the merchandise, while descendants of Polynesians royalty worked the plantations or one of three small resorts in our newest paradise.

Anyway, we had a good look around, savored a $10.00 cup of vanilla ice cream, and made arrangements for rental bikes. Tony opted out. He felt a big lazy coming on, and I wondered, maybe a short ‘howdy’ to the two strange boats with the skinny crew. Denise, who loves all living creatures, played with free-range animals of every sort, motivating her to write home:

“Animals seem to speak my language. Pigs, dogs, cats, goats, and even horses follow me everywhere. I take food scraps in my bag. Skip’s expecting them to swim out to the boat.”

Denise plopped a line in the water, hooking three ugly “triggerfish” in minutes. She tossed them back, explaining, “Some reef fish are poisonous, so why take a chance? They’re probably mutations from the French, Commie (Russian), and US nuclear testing right after World War Two.”

Denise and I rode bikes the next day till our bums were sore and legs ready to part from our hips. Being ashore required different muscles.

The peaceful little retreats we found made the effort worthwhile. At one spot, we met a young man and his German Shepherd, thriving on and living for each other’s company. There was a seawall with a small landing ramp next to it. The man would throw a stick and his powerful Shepherd would leap from the wall, plunge into the water with feet spread, retrieve the stick, and bring it to his best friend. He was an American from Redondo Beach, Ca. cruising the Pacific in his Cal 25 (25ft. sloop) and Cheyenne, the Shepherd, was his crew and companion. The couple, so to speak, were two years into their voyage—a remarkable story of love and adventure.

While on Tahaa we saw remains Denise and I first thought were ancient sacrificial sites, where maidens were possibly offered to the Gods during fiery, lust-filled gatherings of warring chiefs. We learned later, from a respected Hawaiian scholar, that we had been mistaken. The crumbled remains were likely temples for learning called maraes (meeting places). We inspected one close to the shore of Raiatea that allegedly had been a place of learning for priests and navigators from all over the Pacific. The eerie shapes left us still believing there had been sacrifices by the shore where once temples may have stood. The unforgettable site so close to water’s edge caused us to wonder if there was more to learn, because centuries of rising water may have swallowed the evidence.

Denise at unknown ruins on Raitea

Denise offered a thought: “You could be in trouble here, Skip.”

“Yeah . . . why?”

“Your reddish hair. Long ago, redheads from Peru, like your idol Thor Heyerdahl, came here from South America, mingled with the natives, had babies, and devastated the stronger natives because they carried some ill-gotten recessive gene. Maybe they burned redheads to get rid of them. So, Skippy—you better watch out for what peeks at you from yonder palm trees.”

“Geeze, Denise, where in dickens did you come up with that one?” “Nursing school. We studied about what happened on Easter

Island. If it happened there, why not here?”

It made sense. I agreed. We saw several more such maraes during our stay. Homes with tombstones in the front yard were another unusual sight.

“Nothing like being laid to rest at home so friends passing by may wave or whistle a tune,” I said to Denise, “though it could be a hurdle for a real estate broker.”

“It’s not so funny, Skip.” Denise didn’t care for my frivolity: “Some cultures wanted their ancestors close by. It showed respect, and you should get some.”

I apologized to Denise—and the deceased.

Before leaving for Bora Bora, we needed to replenish our dwindling wine and beer supplies. Price labels on the wine bottles in local stores were astronomical. “Robbery is one thing . . . rape another,” I said to Denise as we scoured the isles of Won Ton’s Wonder Store, a colossal trap for outdated trinkets and unsalable merchandise. It pissed me off to be robbed so blatantly. The price labels were old style, not the break-apart ones used to deter thieves in the USA. I couldn’t resist. The robbed became the robber. I switched labels on several bottles. Advantage—mine. But would it come back to haunt me?

There was one more thoughtful chore before leaving the island. The German had hired a small bulldozer to push his grounded yacht back into the sea. The steel jaws and teeth of the machine, operated by the island’s finest bumbling unskilled labor, would certainly chew holes in or mar this gracious little twenty-eight-foot yacht. So a group of us, sans the skinny suspected druggies, spent a morning placing pieces of timber over the leading edge of the machine to soften the jaws’ contact. Additionally, we dug a shallow moat from behind the yacht to the water and lined it with wood so the boat would have a smoother ride to the sea.

A crowd gathered as we made final preparations and the German yelled, “Fire her up.” Even with our prep work, it took ten additional full-muscled men to guide the small vessel to its relaunch. It worked though—and we felt the comforting inner glow one gets from helping another person. The German must have felt it too. He offered warm beer to anyone who wanted it, which was everyone.

We could feel the lure of Bora Bora pulling us. It was said to be the world’s most beautiful island.