Chapter 3

A Brief History of Philosophies That Guide Human Societies

There are three important philosophical “isms” that are part of most belief systems even today: dualism, material monism, and monistic idealism.

The most popular one, dualism, is also the oldest. Dualism is empirically “obvious” in our own experience because of its internal/external dichotomy. No doubt this is the reason for its popularity. In religious thinking, dualism exists as a God/world dualism: God is separate from the world but exerting influence (downward causation) on it. This dualism has dominated humanity for millennia, especially in the West. But in 17th-century Europe, René Descartes formulated a “modern” version of mind-body dualism, with the mind being God's territory, where we have free will, and the body (physical world) being the territory of deterministic science. This Cartesian dualism—a truce between science and religion—has been very influential on subsequent Western academic philosophical thinking. It also defined the modern era of Western philosophy: modernism.

Before modernism, Western society was in the severe doldrums of the Dark Ages, when religion (in the form of Christianity) ruled unchallenged over society. Modernism freed the scientists from the grip of religion. They then set out to discover the meaning of the material world—the laws of nature—in order to gain power and control over it. And this they did with such gusto, with a technology of such unquestioned virtuosity, that their spirit pervaded all of Western society. Soon religious hierarchy and feudalism gave way to democracy and capitalism, the crowning achievements of a modernist society.

Soon after, buoyed by the success of science, people began to question the necessity for this truce between science and religion. In truth, dualism does not stand up well to such obvious questions as these: How do the two bodies made of two entirely different substances interact? How does God of divine substance interact with the material world? How does a nonmaterial mind interact with the material body?

This interaction is impossible, if we allow only local interactions that are mediated by energy-carrying signals going through space and time from one body to another. An interaction between nonmaterial and material would be a violation of physics' sacrosanct law of conservation of energy, which states that the total amount of energy in an isolated system remains constant, although it may change in form. Also, there is the thorny question about the means by which this interaction would occur. What is the mediator signal made of? We seem to need a mediator made of both substances, but none exsists!

Thus material monism arose as the alternative to dualism. In material monism, the difficulties of dualism are avoided by simply insisting that there are not two substances—there is only physical matter. So, consciousness, God, our minds, and all our internal experiences are the results of the brain's interactions. These are ultimately traceable to the interactions of elementary particles (upward causation).

This philosophy has gained much credibility recently. This is not only because of its simplicity, but also because such conglomerates of elementary particles as atomic nuclei have been verified in spectacular form (nuclear detonations).

But the success of material monism also put a damper on the modernistic spirit of the West and a postmodern malaise set in. After all, if materialism holds true, then we cannot conquer and control nature as we thought we could when modernism prevailed. Instead, we humans, like the rest of nature, are determinate machines. We do not have free will or the freedom to pursue meaning as we see fit. Instead, there is no meaning in the mechanistic universe. Under the circumstances, the best we can do is to subscribe to the philosophy of existentialism: there is no meaning to our lives—each of us as an individual creates meaning (essence) in his or her life. After all, we exist somehow. Since we cannot deny our existence, we might as well play the game as it seems to be demanded of us. We pretend that meaning exists and that love exists in an otherwise meaningless, loveless universe.

This existential and pessimistic escape to nihilism—the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche put the message well, “God is dead”—did not last long, however. Some scientists fought back with holism, a new idea that came from a South African politician, Jan Smuts, in his book, Holism and Evolution, in 1926. It was originally defined as “the tendency in nature to form wholes that are greater than the sum of the parts through creative evolution.” Many scientists refused to relinquish God and religion entirely; in holism, they saw an opportunity to recover a God of sorts.

In certain primitive, animistic thinking, God exists as an immanent God, a nature God. The idea is that nature itself is animated with God. You don't have to look for God outside of this world; God is right here. Using holistic language, this can be made into an attractive philosophy. The whole cannot be reduced to its parts. Elementary particles make atoms; but atoms are a whole and cannot be completely reduced to their parts, the elementary particles. The same thing happens when atoms make molecules; something new emerges in the whole that cannot be reduced to the atomic level of being. When molecules make the living cell, the new holistic principle that emerges can be identified as life (Maturana and Varella, 1992; Capra, 1996). When cells called neurons form the brain, the new emergent holistic principle can be identified as mind. And the totality of all life and all mind, the whole of nature itself, can be seen as God. Some people see it as Gaia, the earth mother, following the ideas of chemist James Lovelock (1982) and biologist Lynn Margulis (1993).

Concurrently, this holistic thinking gave rise to the ecology movement—the preservation of nature—and to the philosophy of deep ecology (Devall and Sessions, 1985)—spiritual transformation through the love and appreciation of nature itself. But materialist scientists make the valid point that matter is fundamentally reductionistic, as myriad experiments show; therefore, holism is philosophical fancy.

But there has been another alternative to dualism since antiquity: monistic idealism. Interestingly, in Greek thinking (which most influenced Western civilization), monistic idealism (enunciated by Parmenides, Socrates, and Plato) and material monism (formulated by Democritus) are almost of equal age. Dualism gets compromised because it cannot answer the question about the mediator signals that are necessary for the dual bodies to interact with one another. Suppose there are no signals; suppose the interaction is nonlocal. What then?

Human imagination and intuition reached such heights early on and formulated non-dualism or monistic idealism (also called perennial philosophy). God interacts with the world because God is not separate from the world. God is at once both transcendent and immanent in the world.

For the mind-body dualism, we can think idealistically in this way. Our internal experience, the abode of the mind, consists of a subject (that which experiences) and internal mental objects, such as thoughts. The subject experiences not only the internal objects, but also the external objects of the material world. Suppose we posit that there is only one entity, call it consciousness, which becomes split in some mysterious way into the subject and the objects in our experience. Consciousness transcends both matter and mind objects and is also immanent in them. In this way, the religious and philosophical languages become identical except for minor linguistic quibbles.

This philosophy of monistic idealism was never popular simply because transcendence is difficult to understand without the concept of nonlocality, a quantum concept. Even more obscure are such subtleties of the philosophy as stated in the sentence, “Everything is in God, but God is not in everything.” The meaning of the sentence is that God can never be fully immanent; there is always a transcendent aspect of God. The infinite can never be fully represented in finitude. But try to explain that to the average person!

Nevertheless, monistic idealism has been very influential in the East, in India, Tibet, China, and Japan, in the form of religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, and Taoism. These religions, not being organized hierarchies, always responded to the messages of mystics who from time to time reaffirmed the validity of the philosophy based on their own transcendent experience.

Mystics also existed in the West. Jesus himself was a great mystic. Following his lead, Christianity in the West has had other great mystics who have propounded monistic idealism, mystics such as Meister Eckhart, Saint Francis of Assisi, Saint Teresa of Avila, Saint Catherine of Genoa, etc. But the organized nature of Christianity drowned out the voices of the mystics (ironically, including Jesus), and dualism has prevailed in the official thinking of Christendom.

How do you recognize a mystic? These people have taken a quantum leap from their ego-mind to discover directly that there is existence, awareness, and bliss beyond the ego that is far greater in potential than what we ordinarily experience. But alas! The mystical breakthrough to a “more real” reality does not produce any immediate behavioral transformation (especially in the domain of base emotions). Therefore, behaviorally speaking, most mystics are usually no more impressive than ordinary people. We have to take the mystics' word for their “truth”—and scientists and social leaders through the ages have been reluctant to do that!

There is also a serious drawback to traditional philosophical formulations of monistic idealism. Everything is God or consciousness, so how real is matter, how important? Here most idealist philosophers take the view that the material world is irrelevant, illusory, only to be endured and transcended. True, a few idealist philosophers have emphasized the importance of the material by stating that only in the material form can one exhaust karma, which the soul must do in order to be delivered from the necessity of reincarnating time after time in physical form in the material world. But overall, there has always been an asymmetry in the outlook of idealists regarding consciousness and matter. Consciousness is the true reality, and matter is an epiphenomenon bordering on trivial. This is very similar to a reverse of the materialist belief that consciousness, mind, and all that internal stuff of our experience are trivial, lacking causal efficacy (a relation between one or more of the properties of a thing and an effect of that thing). For a complete, integral study of consciousness, we must rise above both of these attitudes.

EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL DOMAINS OF CONSCIOUSNESS, STRONG AND WEAK OBJECTIVITY

Obviously, the materialist studies of consciousness—neurophysiology, cognitive science, and so on—are limited by the belief system of the researchers, but no one can doubt that the data these researchers collect are useful. And the materialist theories, albeit incomplete, are useful too. Similarly, the data and theories garnered by mystics and meditation researchers through introspection of the internal, which leads to many reported higher states of consciousness (in addition to ordinary states), must also be regarded as meaningful and useful.

Recognize that what the materialist science studies is the third-person aspect of consciousness (behavioral effects), on which reaching a consensus is easy. The data satisfies the stringent criterion of strong objectivity—it is largely independent of the observer. In contrast, the mystics and meditation researchers study the first-person aspect of consciousness (felt experiences). We must realize that the data these latter researchers provide have similarities, and therefore they lead to a consensus about the higher states of consciousness. But we do have to relax the criterion for judging the data, from strong objectivity (observer independence: no subjective data are acceptable) to weak objectivity (observer invariance: the data are similar from one observer/subject to another). Note that typically in laboratory experiments of cognitive psychology, we already accept weak objectivity as the criterion for data on ordinary states of consciousness. Note also that, as the physicist Bernard D'Espagnat (1983) noted long ago, the probabilistic nature of quantum physics is consistent only with weak objectivity.

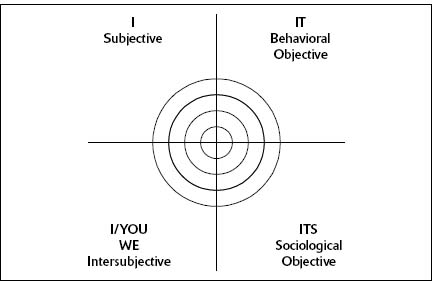

We can add to this summation another quadrant, the intersubjective experience—the scantly studied data on internally experienced aspects of relationships. And to make it all symmetric, we can add a fourth quadrant, consisting of objective data about conglomerates of people, such as entire communities. In this way, we get the four-quadrant model (figure 3-1), thanks largely to the philosopher Ken Wilber (2000).

FIGURE 3-1. The four quadrants of consciousness according to Wilber.

However, while this phenomenological coup may seem like an integrated approach, in truth it is just a beginning. Dichotomies remain in each quadrant; also, no real integration of all the quadrants has been achieved. The philosopher's position is elitist: one cannot integrate using reason or science. To see the integration, one has to achieve higher states of consciousness.

Can we overcome the philosopher's prejudice that science applies only to the material level of reality and reason can never be extended to treat higher levels of consciousness? I think that this prejudice originated in the philosopher's belief in a hidden dualism of consciousness and matter, of interior reality and exterior reality. The philosopher then tries to avoid the problem of interactionism (how consciousness and matter interact) by claiming that science applies only to the exterior (matter) and not to the interior (consciousness), so that there is no need to bother about how the two interact.

When the true meaning of quantum physics is understood, it becomes clear that consciousness cannot be a mere phenomenon of the brain. Furthermore, there is no need to undermine mind and other internal objects as epiphenomena of the brain and the body. Instead, quantum physics and all science must be based on the philosophy of monistic idealism: consciousness is the ground of all being, in which matter, mind, and other internal objects exist as possibilities. But there is no reason to undermine matter either. Matter in its capacity to represent subtle mental states is as important as the subtle (nonmaterial) that it reflects. In other words, quantum thinking allows us to treat mind and matter, internal and external experiences on equal footing, extending causal efficacy and importance to both.

In this way, philosophically and scientifically (with theory and evidence), we have solved the metaphysical problem of which “ism” is accurate and valid—monistic idealism. However, materialist thinking has created a wound in the collective psyche of humanity that, unattended and unhealed, is only getting worse. Our primary job now is to help heal this wound by sharing the philosophical and scientific message of unity that is emerging with all of humanity.

As modernists, we have acknowledged the veracity of the mind and what it processes: meaning. This has led to a much more expansive participation in the adventurous exploration of meaning. As modernism has given way to the postmodern malaise of meaningless materialism, our institutions and their progressive legacy of democracy, capitalism, and liberal education have been put in jeopardy. They are being undermined to create a new kind of hierarchy, setting new limits on freedom that are no better than the limits imposed in the past by church and feudal domination. This time, the shackles are materialist science and scientism.

Monistic idealism can lead to a new kind of modernism that I call transmodernism, following the philosopher Willis Harman. Descartes' dualistic modernism was based on the motto, “I think, therefore I am.” In other words, if there is a thought, there must be a thinker. This released the thinking mind for new exploration, but mainly for inventions intended to solve problems. Inventions require creativity, but only a limited version of it that I call situational creativity, which is designed to solve a problem within a known context of thinking. Situational creativity is important, but in some real sense, it is also more of the same: it is “thinking inside the box.” Transmodernism is based on the motto, “I choose, therefore I am.” It releases the true potency of the creative mind, not only situational creativity but also what I call fundamental creativity: the ability to change the contexts on which thinking is based and choose new ones.

Under modernism, we got not only the benefits of democracy and capitalism, but also the evils of modernism: thinking that put humans over nature and the domination of thinking over feeling, which I call the mentalization of feeling. Yes, we have created useful industry and technology, but we have also created environmental problems that we don't know how to solve.

We need to bring back the modernist spirit and the emphasis on mental exploration, but without its dark side, its attitudes of human-over-nature and reason-over-feeling, and without the almost total dependence on simple hierarchies and the ego isolation of the lone individual. The new era of transmodernism begins with a quantum leap in our attitudes—from human over nature to human within nature, from reason over feeling to reason integrated with feeling, from simple hierarchies to tangled hierarchies, from ego separateness to the integration of the ego and quantum consciousness/God. Then we are truly back on track for the emergence of a new age of ethical living.

OLD SCIENCE AND THE NEW SCIENCES: PARADIGM SHIFT

I introduced the idea of a paradigm shift in science in chapter 1. The old science is based on the supremacy of matter, material monism, with its reductionism and upward causation. The new holistic paradigm does not give up the material monism: everything is matter. But it does give up the idea of reductionism and opts for the philosophy of holism: the whole is greater than its parts and cannot be reduced to its parts. Here God and spirituality are recovered in the sense of an immanent God, or a “Gaia consciousness” immanent throughout the whole world with all its organisms. (The Gaia hypothesis or theory, developed by James Lovelock, represents all things on earth, living and nonliving, as a complex system of interactions that can be considered to be a single organism.) There is also something like downward causation, a causal autonomy of the emergent holistic entities at each level of organization that cannot be reduced to the parts. Alas! This causality is not real, because in the final reckoning it too is determined from material interactions, that is, from upward causation.

The newest science, science within consciousness, is based on quantum physics and the primacy of consciousness (monistic idealism), and it is inclusive of the old reductive paradigm. In science within consciousness, God is a real, causally efficacious agency, intervening through downward causation. In science within consciousness, we can even treat subtle bodies without the usual problems of interaction dualism. In science within consciousness, we can address within science the evolution of godliness that religions aspire to achieve. And yet the old science remains valid—in its own domain. In the material domain of conscious experience, consciousness chooses the actual event of manifest reality out of the quantum possibilities determined by the upward causation from the material substratum. And since quantum effects are relatively muted for gross matter, gross material behavior is approximately deterministic.

In truth, even reductionistic materialists make some room for God. In a book called Why God Won't Go Away Andrew Newberg and Eugene D'Aquili (2001) cited recent work in neurophysiology to suggest that God and spiritual experiences can be explained simply as brain phenomena.

In a similar vein, the holists maintain that God and spirituality can be understood and explored as an emergent holist phenomena of matter itself; even free will and downward causation can be understood as emergent apparent autonomy of higher levels of organization of matter.

The paradigm explored and endorsed in this book is much more radical than either of these two approaches to God. I posit that the ground of being is consciousness, not matter. I posit that not only matter but also a subtler vital energy body, an even subtler mind, and an even subtler supramental body all exist as quantum possibilities of consciousness. These develop in time from causal interactions in their respective domains. I also posit that as we evolve we move through manifest states of consciousness that are greater and greater manifestations of godliness—the qualities of God, the supramental archetypes. The price we pay for including the subtle in our science is multiculturalism of theory and weak objectivity for sorting data.

I must emphasize once again that the God for which I present scientific data is quite the same as the God envisioned by mystics and the founders of all of the world's great traditions, although the teachings of the great religions have become diluted into dualism in their popular renditions.

Toward the end of the 19th century, the philosopher Nietzsche pronounced through one of his fictional characters that “God is dead.”This reflected Nietzsche's uneasiness about the effectiveness of a naïve popular Christianity to uphold ethics and morality against the materialist science that was rapidly sweeping the West. In other words, Nietzsche realized that the popular dualistic Christian God was dead. I show in this book that in the new paradigm of science based on the primacy of consciousness and quantum physics, God lives on eternally as the agent of downward causation, in a role that should prove satisfactory to both science and religion.

Irrespective of whatever picture of God currently satisfies you the most, I hope you will give the evidence and theory presented here a fair appraisal. After all, God has been a preoccupation of human beings for millennia, a preoccupation that I suspect has affected you at least a little. I merely ask that you suspend your judgment and disbelief while you read Parts Two, Three, and Four, in which I present the evidence.