Chapter 6

Downward Causation in Psychology: The Distinction Between Conscious and Unconscious

By all accounts, Sigmund Freud was an atheist. He ridiculed spiritual oceanic experiences as examples of infantile helplessness. He broke with Carl Jung, his most promising protégé, because Jung tended to take religion seriously. So why is the theory that Freud founded, psychoanalysis, held in such ridicule by a Nobel Prize-winning materialist, the physicist Richard Feynman? Here is what Feynman (1962) said:

Psychoanalysis is not a science: it is at best a medical process, and perhaps even more like witch-doctoring. It has a theory as to what causes disease—lots of different “spirits,” etc.

So Feynman seems to be saying that psychoanalysis has a lot of concepts, such as the unconscious, that smack of the witch doctor's “spirits.” Materialists don't like the unconscious, because with materialism it is quite impossible to distinguish between the conscious and the unconscious. In 1962, when Feynman wrote the comments above, he also said, “Psychoanalysis has not been checked carefully by experiment.” But now the unconscious, the most important idea of psychoanalysis, has been thoroughly verified from quite a few different angles. And this has opened up another impossible question for the materialists.

So does the God hypothesis and downward causation help us distinguish between the unconscious and the conscious? You bet!

QUANTUM MEASUREMENT IN THE BRAIN AND THE UNCONSCIOUS-CONSCIOUS DISTINCTION

How do we perceive a stimulus that involves measuring it? How do we measure it? The crucial point is to recognize that in every event of perception and its quantum measurement, we not only measure the object we perceive, but also the state of the brain. Before we measure, the object is a wave of possibility, but so too is the stimulus that the brain receives from a possibility, a stimulus in possibility. And upon receiving such a stimulus, the brain too becomes a wave of possibility, a bundle of possible brain states. When we choose the state that actualizes the object we perceive, we also have to choose from among the possible brain states.

Face it. There is a paradox here. The brain (and the object/stimulus) remains in possibility until a choice among its possible states has been made. But without a brain, we cannot say that there is an observer, a subject's I (albeit in unitive consciousness) that is doing the choosing. This is a circularity that we call a tangled hierarchy, a concept that I introduced in the last chapter.

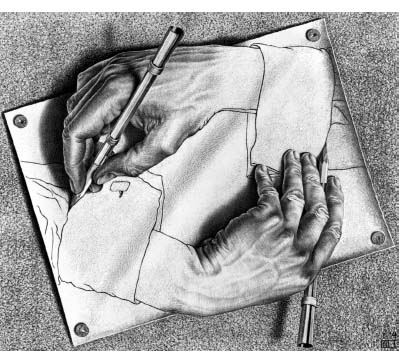

Simple hierarchy occurs when one level of a hierarchy causally controls the other(s). Figure 1-1 (page 17) depicts a simple hierarchy. To understand a tangled hierarchy, examine the Escher picture, “Drawing Hands” (figure 6-1). It is a tangled hierarchy because the left hand is drawing the right hand as the right hand is drawing the left hand. The causal control oscillates. (This is a version of the old question, “Which came first, the chicken or the egg?”) The tangle can be seen clearly and also be resolved by “jumping out of the system,” thinking outside the frame, realizing that neither hand is drawing the other—Escher is drawing them both. We cannot see the tangled hierarchy if we remain within the infinitely oscillating system. Instead, we get stuck and think of ourselves as separate from the rest of the world. In this way, a tangled hierarchy gives the appearance of self-reference (Hofstadter, 1980).

FIGURE 6-1. “Drawing Hands” by M.C. Escher. An example of tangled hierarchy.

So, quantum measurement involving the brain is tangled-hierarchical. The reward is that we gain the capacity for self-reference, the ability to see ourselves as a “self” experiencing the world as separate from us. The downside is that we don't realize that our separateness is illusory, arising from a tangled hierarchy in quantum measurement, a quantum collapse. Quantum measurement in the brain is special because of this tangled hierarchy involved in the passage from micro to macro in the neurophysiological processing of an external stimulus leading to perception.

Neurophysiologists try in vain to decipher the stages in which a stimulus is processed. Take an optical stimulus, for example. A photon from the object arrives at the retina of an eye and then travels along a nerve as an electrical stimulus to a brain center, etc, etc. To their credit, the neurophysiologists can do the analysis for a bit, but then everything gets jumbled up. The brain is too complex.

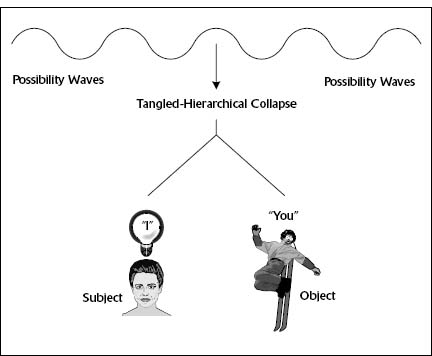

We can, however, recognize what is involved in the final reckoning. For a quantum measurement to have taken place in the brain, there must be a series of apparatuses that process and amplify the stimulus, taking it from the microscopic scale to the macroscopic scale. Somewhere in this passage from the micro level to the macro level, the tangled hierarchy is created because there is an infinite feedback loop that is impossible to decipher or break down into steps. We cannot follow the steps logically, but we can depict the end result—self-reference, as in figure 6-2. Finally, what we perceive is the object that sent the stimulus. We do not perceive the brain state, the brain representation of the object; instead, the unitive consciousness identifies with the brain state collapsed and memorized, and experiences itself as the subject of the collapsed object.

FIGURE 6-2. Tangled hierarchical quantum measurement of an object/stimulus in the brain produces not only the experience of the object, but also the experience of the subject in our consciousness.

Whenever there is such a tangled hierarchy in a quantum measurement situation, there is self-reference: the subject that perceives (senses) and the object that is perceived (sensed) arise codependently.

So what is the distinction between unconscious and conscious? Unconscious is when there is processing but no collapse. Possibility objects interact with other possibility objects in the unconscious, expanding in possibility. There is consciousness and processing, but no awareness. We call this unconscious processing, that is, processing without collapse, without subject-object awareness. And then there is the conscious, when there is collapse, when there is subject-object split awareness.

We can go through essentially the same analysis for a mental object of meaning. We recognize that the mental object cannot collapse of itself; there is no micro-macro division within the mind, no tangled hierarchical measurement-aid apparatus. But mental meaning can correlate with a physical object. When the physical object is collapsed, the correlated mental meaning collapses. In this way, the brain memory that results from a particular collapse event is not only a memory of the physical object, but associatively also a memory of the mental meaning. We can say that the brain has made a representation of the mental meaning.

Let's go back to Freud and his concept of the unconscious. Freud created some confusion with his language. What he called “unconscious,” he should have called “unaware.” When we recognize that consciousness is primary, we also realize that consciousness is always present. It is the ground of all being, so where would it go if there's an unconscious?

Freud's concept of the unconscious is actually much narrower than what quantum physics indicates. Quantum consciousness that collapses an original stimulus, an object—mental and/or physical—that we have never before encountered, is experienced in its full creative and unconditioned glory. The unconscious processing that precedes such a collapse event is also unrestricted, unlimited by conditioning. This is more like the concept of collective unconscious that Jung introduced in psychology. (This concept, which Jung later labeled the objective psyche, is the set of typical modes of feeling, thought, expression, and memory that seem to be innate to all human beings.) In contrast, what Freud originally meant by “unconscious” can be called our personal unconscious.

Let's examine the difference more clearly. Memories accumulate in the brain as we experience and learn about our stimuli. More and more, as our unconscious processes our memories, the tendency is to process every stimulus in terms of what we remember from previous experiences of stimuli. Soon we develop a habit pattern in which we use our mind to give meaning to our experiences, a pattern that we call our character. This character, plus the accumulation of our memory/history, is the quantum physics version of what psychologists call the personal self or the ego. The ego also subverts the tangled hierarchy of primary experiences into a simple hierarchy (one level causally controlling the other) in which the ego chooses within the context of its learned “programs.”

Now to Freud's concept of the personal unconscious. Some of our experiences are traumatic, so much so that we are extremely reluctant to experience them ever again. However, they are acquired by our memory, just as are all experiences. So we develop an extreme resistance against retrieving any of those memories. Even in our conditioned ego, we retain the power of intention, of refusing to collapse a possibility. In this way, the possibilities we want to avoid experiencing, we are most often able to avoid. Unfortunately, unconscious processing of what we thus suppress continues without our control. So the repressed memory affects the overall processing of new possibilities, sometimes producing reactions that cause what we can call deviant, irrational, or mentally sick neurotic behavior. Freud's description was simpler but quite to the point: the unconscious id acts as a force to make us behave in ways that we cannot explain through a stream-of-consciousness analysis of our behavior. Our behavior has become irrational.

In materialist thinking, all is the play of the forces of upward causation. There is no room for the force of an unconscious id, which would cause havoc in the world of behavioral psychology, the psychology of conditioned behavior. So Freud's psychoanalysis is anathema, voodoo psychology to the materialist.

So although Freud was an atheist, his psychology of the unconscious, now called depth psychology, gives us indisputable evidence for downward causation or for what is its agency, God. The causal power of the unconscious id originates from the divine power of downward causation that we retain, albeit in a limited sense, even in our conditioned ego.

THE COLLECTIVE UNCONSCIOUS

Whereas Freud's discovery of the personal unconscious acknowledged a trickle of the potential power of downward causation, in Jung's conceptualization of the collective unconscious, that trickle became a mighty torrent. The collective unconscious holds our collective nonlocal memory, said Jung. Its movements, of which we are unaware, erupt in our awareness in the form of archetypal experiences in creativity and “big” dreams. (Jung used the term “big dream” to refer to a dream that contains universal significance, that is important because of the universality of its images, archetypes.) They also precipitate events of synchronicity in which the archetypes of the collective unconscious show their “psychoid” nature: they causally affect not only events in the psyche, but also events outside the psyche, in the physical reality itself.

The concept of synchronicity implies no less than the power of downward causation of consciousness (God) mediating between matter and psyche. No wonder when somebody once asked Jung, “What do you think of God?” Jung promptly replied, “I don't think. I know.” And Jung also said, “Sooner or later nuclear [quantum] physics and the psychology of the unconscious will draw closer together as both of them, independently of one another and from opposite directions, push forward into transcendental territory, the one with the concept of the atom, the other with that of the archetype” (Aion, 1951).

A little clarification of terminology is needed here. What Jung called the collective unconscious is what we identify as the unmanifested consciousness, most of which belongs to the supramental domain. Jungian archetypes are the mental representations of the Platonic archetypes (supramental forms or ideas or patterns according to which all things are constructed, which are understood by insight, as if by recollection, rather than by perception through the senses), which define movement in the supramental domain. From prehistoric time, human beings have intuited these archetypes and represented and labeled them; they are the gods and goddesses of our mythology.

Whereas Freud's vision of downward causation is myopic—it deals only with pathology—Jung's vision is far-reaching: it concerns the human potential, which, according to Jung, is “to make the unconscious conscious,” to make the unmanifest manifest. For Jung, the human potential culminates when we have represented and integrated all the archetypes of our unconscious and actualized our Self. Then we are “individuated.”

The new science agrees with Jung and accordingly chalks out an evolutionary pathway for humans striving toward individuation.

DIRECT EVIDENCE FOR UNCONSCIOUS PROCESSING

There is now a lot of direct evidence for the unconscious and for unconscious processing. The first piece of evidence is a striking phenomenon called blindsight (Humphrey, 1972). There are people who are cortically blind (experiencing a loss of vision because of an abnormality of the visual cortex of the brain), but who have vision processing in their hindbrains that is entirely unconscious. (The hindbrain is basically a continuation of the spinal cord; it receives incoming messages first and controls functions of the autonomic nervous system such as breathing, blood pressure, and heart rate.) In other words, a blindsight person can “see” via the hindbrain (unconsciously) and behave accordingly, but since this person is not seeing with his visual cortex (consciously), he would deny it. In a typical experiment, these seemingly blind people would be asked to travel in a straight line that contains an obstacle. The data show that the subjects would always go around the obstacles, but when the experimenters asked them why they deviated from their straight-line path, they would be puzzled and say, “I don't know.” Clearly, they were processing or “seeing” the obstacles unconsciously but were unaware of them.

Like the processing by the hindbrain, processing by the right cortical hemisphere (the right brain) is also entirely unconscious. Experiments have been carried out with split-brain patients, whose left and right brains are surgically disconnected (that is, the main link, the corpus callosum, has been severed), except for the cross connections in the hindbrain centers involved with the processing of emotions and feelings. In one experiment, the experimenter projected the picture of a nude male model into the right brain hemisphere of a female subject in the midst of a sequence of geometrical patterns. The subject blushed, but when asked why, she couldn't explain. Seeing the nude picture and the feeling of embarrassment must have been processed unconsciously.

The best available data for unconscious processing, in this author's opinion, are collected in connection with near-death experiences. Some people after a cardiac arrest die clinically (as shown by a flat EEG reading), only to be revived a little later through the marvels of modern medicine (Sabom, 1981). Some of these near-death survivors report having witnessed their own surgery, as if they were hovering over the operation table. They are uncannily able to give specific details of their operations that leave no doubt that they are telling the truth, however difficult it is to rationalize their autoscopic vision in their near-death experience. Well, they are not “seeing” with their local eyes, with signals—that much is clear. Indeed, even blind people report such autoscopic vision during their near-death comas (Ring and Cooper, 1995). These patients are “seeing” with their nonlocal, distant-viewing ability using the eyes of others involved with the surgery—doctors, nurses, etc. (Goswami, 1993). But this is only half of the surprise that the data present.

Try to understand how they can “see” even nonlocally while they are “dead,” unconscious, and quite incapable of collapsing possibility waves. This is through unconscious processing, of course, which is like the people with blindsight, except that, unlike the latter, the near-death survivors have memories of what they processed while unconscious (Van Lommel et al., 2001). A chain of uncollapsed possibilities can collapse retroactively in time. This has been verified in the laboratory via the delayed choice experiment. (See chapter 7.) For the near-death survivor, the “delayed” collapse takes place at the moment the brain function returns, as noted by the EEG, precipitating a whole stream of collapses going backward in time.

The near-death data may be the most impressive, but the most important evidence of unconscious processing occurs in the phenomenon of creativity.

UNCONSCIOUS PROCESSING IN THE CREATIVE PROCESS

We discussed the discontinuous quantum leap of creativity earlier. It is important to recognize that the discontinuity of creativity is not an isolated event. If it were, a scientific study of it would be relatively fruitless because of a total lack of control. Fortunately, this is not the situation.

It is now well established that the creative process consists of four distinct stages (Wallas, 1926): preparation, unconscious processing, insight, and manifestation. The first one and the last are obvious: preparation is reading up and getting acquainted with what is already known; manifestation is capitalizing on the new idea, obtained as insight, by developing a product. These stages are both done more or less in a continuous fashion and with a lot of control. But the middle two processes are more mysterious. They are the analogs of the two stages of quantum dynamics: the spreading of the possibility wave and the discontinuous collapse.

As already discussed, unconscious processing is processing during which we are conscious but unaware. In creativity, unconscious processing accounts for the proliferation of the ambiguity of thought. Its analog is the spreading of the quantum possibility wave between measurements. Creative insight, of course, is sudden and discontinuous. As discussed in chapter 5, it is the analog of the electron's quantum leap from one orbit to another without going through the intervening space. An insight is a discontinuous quantum leap from one thought to another without thinking through the intermediate steps. Unconscious processing produces a multitude of possibilities; insight is the collapse of one gestalt of these possibilities (a new one of value) into actuality. (More on this in chapter 17.)

In this way, the creative process is an undeniable mixture of both continuity and discontinuity. The discontinuity we cannot control, but the continuity we can. And this makes creativity a scientifically tractable phenomenon.

THE GUIDING RULES OF THE NEW SCIENCE

I want to make an important point in passing. Every new paradigm of science brings along some modifications of the old standards of measurement. Before physics delved into the study of submicroscopic objects, the standard of observation was a strict “seeing is believing” or “show me.” But submicroscopic objects like electrons cannot be seen in the old sense, with the naked eye. So we had to modify what constitutes seeing to include seeing via amplifying apparatuses. Next came quarks: they don't even exist in daylight, only in confinement. So now our concept of seeing in physics is further relaxed to mean seeing the indirect effects of quantum objects.

In creativity, the creator (the chooser of the insight) is the objective quantum consciousness. But the mental representation of the insight is made in the subjective ego, and through this subjectivity enters. Does this mean we cannot study creative insights scientifically? No, but we can't apply the criterion of strong objectivity—that events have to be independent of the observers or independent of the subjects. Instead we have to use weak objectivity—the events would have to be observer-invariant, more or less the same for different subjects, but independent of a particular subject. As physicist Bernard D'Espagnat (1983) has pointed out, quantum physics forces weak objectivity upon us already. And even experiments in cognitive/behavioral psychology cannot maintain a strict decorum of strong objectivity.

Above, we find one more relaxation of the protocol of the new science. In the old science, we demand total control and total power of prediction. In the new science, we are happy with partial control and therefore only limited power of prediction. But even with these new protocols, science can guide us adequately—and that guidance is the unique value of science.