Hephaestus (Vulcan)

Hephaestus, the son of Zeus and Hera, was the god of fire in its beneficial aspect, and the presiding deity over all workmanship accomplished by means of this useful element. He was universally honoured, not only as the god of all mechanical arts, but also as a house and hearth divinity, who exercised a beneficial influence on civilized society in general. Unlike the other Greek divinities, he was ugly and deformed, being awkward in his movements, and limping in his gait. This latter defect originated, as we have already seen, in the wrath of his father Zeus, who hurled him down from heaven in consequence of his taking the part of Hera, in one of the domestic disagreements, which so frequently arose between this royal pair. Hephaestus was a whole day falling from Olympus to the earth, where he at length alighted on the island of Lemnos. The inhabitants of the country, seeing him descending through the air, received him in their arms; but in spite of their care, his leg was broken by the fall, and he remained ever afterwards lame in one foot. Grateful for the kindness of the Lemnians, he henceforth took up his abode in their island, and there built for himself a superb palace, and forges for the pursuit of his avocation. He instructed the people how to work in metals, and also taught them other valuable and useful arts.

It is said that the first work of Hephaestus was a most ingenious throne of gold, with secret springs, which he presented to Hera. It was arranged in such a manner that, once seated, she found herself unable to move, and though all the gods endeavoured to extricate her, their efforts were unavailing. Hephaestus thus revenged himself on his mother for the cruelty she had always displayed towards him, on account of his want of comeliness and grace. Dionysus, the wine god, contrived, however, to intoxicate Hephaestus, and then induced him to return to Olympus, where, after having released the queen of heaven from her very undignified position, he became reconciled to his parents.

He now built for himself a glorious palace on Olympus, of shining gold, and made for the other deities those magnificent edifices which they inhabited. He was assisted in his various and exquisitely skilful works of art, by two female statues of pure gold, formed by his own hand, which possessed the power of motion, and always accompanied him wherever he went. With the assistance of the Cyclops, he forged for Zeus his wonderful thunderbolts, thus investing his mighty father with a new power of terrible import. Zeus testified his appreciation of this precious gift, by bestowing upon Hephaestus the beautiful Aphrodite in marriage, but this was a questionable boon; for the lovely Aphrodite, who was the personification of all grace and beauty, felt no affection for her ungainly and unattractive spouse, and amused herself by ridiculing his awkward movements and unsightly person. On one occasion especially, when Hephaestus good-naturedly took upon himself the office of cup-bearer to the gods, his hobbling gait and extreme awkwardness created the greatest mirth amongst the celestials, in which his disloyal partner was the first to join, with unconcealed merriment.

Aphrodite greatly preferred Ares to her husband, and this preference naturally gave rise to much jealousy on the part of Hephaestus, and caused them great unhappiness.

Hephaestus appears to have been an indispensable member of the Olympic Assembly, where he plays the part of smith, armourer, chariot-builder, etc. As already mentioned, he constructed the palaces where the gods resided, fashioned the golden shoes with which they trod the air or water, built for them their wonderful chariots, and shod with brass the horses of celestial breed, which conveyed these glittering equipages over land and sea. He also made the tripods which moved of themselves in and out of the celestial halls, formed for Zeus the far-famed aegis, and erected the magnificent palace of the sun. He also created the brazen-footed bulls of Aetes, which breathed flames from their nostrils, sent forth clouds of smoke, and filled the air with their roaring.

Among his most renowned works of art for the use of mortals were: the armour of Achilles and AEneas, the beautiful necklace of Harmonia, and the crown of Ariadne; but his masterpiece was Pandora, of whom a detailed account has already been given.

There was a temple on Mount Etna erected in his honour, which none but the pure and virtuous were permitted to enter. The entrance to this temple was guarded by dogs, which possessed the extraordinary faculty of being able to discriminate between the righteous and the unrighteous, fawning upon and caressing the good, whilst they rushed upon all evil-doers and drove them away.

Hephaestus is usually represented as a powerful, brawny, and very muscular man of middle height and mature age; his strong uplifted arm is raised in the act of striking the anvil with a hammer, which he holds in one hand, whilst with the other he is turning a thunderbolt, which an eagle beside him is waiting to carry to Zeus. The principal seat of his worship was the island of Lemnos, where he was regarded with peculiar veneration.

Vulcan

The Roman Vulcan was merely an importation from Greece, which never at any time took firm root in Rome, nor entered largely into the actual life and sympathies of the nation, his worship being unattended by the devotional feeling and enthusiasm which characterized the religious rites of the other deities. He still, however, retained in Rome his Greek attributes as god of fire, and unrivalled master of the art of working in metals, and was ranked among the twelve great gods of Olympus, whose gilded statues were arranged consecutively along the Forum. His Roman name, Vulcan, would seem to indicate a connection with the first great metal-working artificer of Biblical history, Tubal-Cain.

Poseidon (Neptune)

Poseidon was the son of Kronos and Rhea, and the brother of Zeus. He was god of the sea, more particularly of the Mediterranean, and, like the element over which he presided, was of a variable disposition, now violently agitated, and now calm and placid, for which reason he is sometimes represented by the poets as quiet and composed, and at others as disturbed and angry.

In the earliest ages of Greek mythology, he merely symbolized the watery element; but in later times, as navigation and intercourse with other nations engendered greater traffic by sea, Poseidon gained in importance, and came to be regarded as a distinct divinity, holding indisputable dominion over the sea, and over all sea-divinities, who acknowledged him as their sovereign ruler. He possessed the power of causing at will, mighty and destructive tempests, in which the billows rise mountains high, the wind becomes a hurricane, land and sea being enveloped in thick mists, whilst destruction assails the unfortunate mariners exposed to their fury. On the other hand, his alone was the power of stilling the angry waves, of soothing the troubled waters, and granting safe voyages to mariners. For this reason, Poseidon was always invoked and propitiated by a libation before a voyage was undertaken, and sacrifices and thanksgivings were gratefully offered to him after a safe and prosperous journey by sea.

The symbol of his power was the fisherman’s fork or trident, by means of which he produced earthquakes, raised up islands from the bottom of the sea, and caused wells to spring forth out of the earth.

Poseidon was essentially the presiding deity over fishermen, and was on that account, more particularly worshipped and revered in countries bordering on the sea-coast, where fish naturally formed a staple commodity of trade. He was supposed to vent his displeasure by sending disastrous inundations, which completely destroyed whole countries, and were usually accompanied by terrible marine monsters, who swallowed up and devoured those whom the floods had spared. It is probable that these sea-monsters are the poetical figures which represent the demons of hunger and famine, necessarily accompanying a general inundation.

Poseidon is generally represented as resembling his brother Zeus in features, height, and general aspect; but we miss in the countenance of the sea-god the kindness and benignity which so pleasingly distinguish his mighty brother. The eyes are bright and piercing, and the contour of the face somewhat sharper in its outline than that of Zeus, thus corresponding, as it were, with his more angry and violent nature. His hair waves in dark, disorderly masses over his shoulders; his chest is broad, and his frame powerful and stalwart; he wears a short, curling beard, and a band round his head. He usually appears standing erect in a graceful shell-chariot, drawn by hippocamps, or sea-horses, with golden manes and brazen hoofs, who bound over the dancing waves with such wonderful swiftness, that the chariot scarcely touches the water. The monsters of the deep, acknowledging their mighty lord, gambol playfully around him, whilst the sea joyfully smooths a path for the passage of its all-powerful ruler.

He inhabited a beautiful palace at the bottom of the sea at AEgea in Euboea, and also possessed a royal residence on Mount Olympus, which, however, he only visited when his presence was required at the council of the gods.

His wonderful palace beneath the waters was of vast extent; in its lofty and capacious halls thousands of his followers could assemble. The exterior of the building was of bright gold, which the continual wash of the waters preserved untarnished; in the interior, lofty and graceful columns supported the gleaming dome. Everywhere fountains of glistening, silvery water played; everywhere groves and arbours of feathery-leaved sea-plants appeared, whilst rocks of pure crystal glistened with all the varied colours of the rainbow. Some of the paths were strewn with white sparkling sand, interspersed with jewels, pearls, and amber. This delightful abode was surrounded on all sides by wide fields, where there were whole groves of dark purple coralline, and tufts of beautiful scarlet-leaved plants, and sea-anemones of every tint. Here grew bright, pinky sea-weeds, mosses of all hues and shades, and tall grasses, which, growing upwards, formed emerald caves and grottoes such as the Nereides love, whilst fish of various kinds playfully darted in and out, in the full enjoyment of their native element. Nor was illumination wanting in this fairy-like region, which at night was lit up by the glow-worms of the deep.

But although Poseidon ruled with absolute power over the ocean and its inhabitants, he nevertheless bowed submissively to the will of the great ruler of Olympus, and appeared at all times desirous of conciliating him. We find him coming to his aid when emergency demanded, and frequently rendering him valuable assistance against his opponents. At the time when Zeus was harassed by the attacks of the Giants, he proved himself a most powerful ally, engaging in single combat with a hideous giant named Polybotes, whom he followed over the sea, and at last succeeded in destroying, by hurling upon him the island of Cos.

These amicable relations between the brothers were, however, sometimes interrupted. Thus, for instance, upon one occasion Poseidon joined Hera and Athene in a secret conspiracy to seize upon the ruler of heaven, place him in fetters, and deprive him of the sovereign power. The conspiracy being discovered, Hera, as the chief instigator of this sacrilegious attempt on the divine person of Zeus, was severely chastised, and even beaten, by her enraged spouse, as a punishment for her rebellion and treachery, whilst Poseidon was condemned, for the space of a whole year, to forego his dominion over the sea, and it was at this time that, in conjunction with Apollo, he built for Laomedon the walls of Troy.

Poseidon married a sea-nymph named Amphitrite, whom he wooed under the form of a dolphin. She afterwards became jealous of a beautiful maiden called Scylla, who was beloved by Poseidon, and in order to revenge herself she threw some herbs into a well where Scylla was bathing, which had the effect of metamorphosing her into a monster of terrible aspect, having twelve feet, six heads with six long necks, and a voice which resembled the bark of a dog. This awful monster is said to have inhabited a cave at a very great height in the famous rock which still bears her name, and was supposed to swoop down from her rocky eminence upon every ship that passed, and with each of her six heads to secure a victim.

Amphitrite is often represented assisting Poseidon in attaching the sea-horses to his chariot.

The Cyclops, who have been already alluded to in the history of Cronus, were the sons of Poseidon and Amphitrite. They were a wild race of gigantic growth, similar in their nature to the earth-born Giants, and had only one eye each in the middle of their foreheads. They led a lawless life, possessing neither social manners nor fear of the gods, and were the workmen of Hephaestus, whose workshop was supposed to be in the heart of the volcanic mountain AEtna.

Here we have another striking instance of the manner in which the Greeks personified the powers of nature, which they saw in active operation around them. They beheld with awe, mingled with astonishment, the fire, stones, and ashes which poured forth from the summit of this and other volcanic mountains, and, with their vivacity of imagination, found a solution of the mystery in the supposition, that the god of Fire must be busy at work with his men in the depths of the earth, and that the mighty flames which they beheld, issued in this manner from his subterranean forge.

The chief representative of the Cyclops was the man-eating monster Polyphemus, described by Homer as having been blinded and outwitted at last by Odysseus. This monster fell in love with a beautiful nymph called Galatea; but, as may be supposed, his addresses were not acceptable to the fair maiden, who rejected them in favour of a youth named Acis, upon which Polyphemus, with his usual barbarity, destroyed the life of his rival by throwing upon him a gigantic rock. The blood of the murdered Acis, gushing out of the rock, formed a stream which still bears his name.

Triton, Rhoda, and Benthesicyme were also children of Poseidon and Amphitrite.

The sea-god was the father of two giant sons called Otus and Ephialtes. When only nine years old they were said to be twenty-seven cubits in height and nine in breadth. These youthful giants were as rebellious as they were powerful, even presuming to threaten the gods themselves with hostilities. During the war of the Gigantomachia, they endeavoured to scale heaven by piling mighty mountains one upon another. Already had they succeeded in placing Mount Ossa on Olympus and Pelion on Ossa, when this impious project was frustrated by Apollo, who destroyed them with his arrows. It was supposed that had not their lives been thus cut off before reaching maturity, their sacrilegious designs would have been carried into effect.

Pelias and Neleus were also sons of Poseidon. Their mother Tyro was attached to the river-god Enipeus, whose form Poseidon assumed, and thus won her love. Pelias became afterwards famous in the story of the Argonauts, and Neleus was the father of Nestor, who was distinguished in the Trojan War.

The Greeks believed that it was to Poseidon they were indebted for the existence of the horse, which he is said to have produced in the following manner: Athene and Poseidon both claiming the right to name Cecropia (the ancient name of Athens), a violent dispute arose, which was finally settled by an assembly of the Olympian gods, who decided that whichever of the contending parties presented mankind with the most useful gift, should obtain the privilege of naming the city. Upon this Poseidon struck the ground with his trident, and the horse sprang forth in all his untamed strength and graceful beauty. From the spot which Athene touched with her wand, issued the olive-tree, whereupon the gods unanimously awarded to her the victory, declaring her gift to be the emblem of peace and plenty, whilst that of Poseidon was thought to be the symbol of war and bloodshed. Athene accordingly called the city Athens, after herself, and it has ever since retained this name.

Poseidon tamed the horse for the use of mankind, and was believed to have taught men the art of managing horses by the bridle. The Isthmian games (so named because they were held on the Isthmus of Corinth), in which horse and chariot races were a distinguishing feature, were instituted in honour of Poseidon.

He was more especially worshipped in the Peloponnesus, though universally revered throughout Greece and in the south of Italy. His sacrifices were generally black and white bulls, also wild boars and rams. His usual attributes are the trident, horse, and dolphin.

In some parts of Greece this divinity was identified with the sea-god Nereus, for which reason the Nereides, or daughters of Nereus, are represented as accompanying him.

Neptune

The Romans worshipped Poseidon under the name of Neptune, and invested him with all the attributes which belong to the Greek divinity.

The Roman commanders never undertook any naval expedition without propitiating Neptune by a sacrifice.

His temple at Rome was in the Campus Martius, and the festivals commemorated in his honour were called Neptunalia.

Sea Divinities

Oceanus

Oceanus was the son of Uranus and Gaea. He was the personification of the ever-flowing stream, which, according to the primitive notions of the early Greeks, encircled the world, and from which sprang all the rivers and streams that watered the earth. He was married to Tethys, one of the Titans, and was the father of a numerous progeny called the Oceanides, who are said to have been three thousand in number. He alone, of all the Titans, refrained from taking part against Zeus in the Titanomachia, and was, on that account, the only one of the primeval divinities permitted to retain his dominion under the new dynasty.

Nereus

Nereus appears to have been the personification of the sea in its calm and placid moods, and was, after Poseidon, the most important of the sea-deities. He is represented as a kind and benevolent old man, possessing the gift of prophecy, and presiding more particularly over the Aegean Sea, of which he was considered to be the protecting spirit. There he dwelt with his wife Doris and their fifty blooming daughters, the Nereides, beneath the waves in a beautiful grotto-palace, and was ever ready to assist distressed mariners in the hour of danger.

Proteus

Proteus, more familiarly known as “The Old Man of the Sea,” was a son of Poseidon, and gifted with prophetic power. But he had an invincible objection to being consulted in his capacity as seer, and those who wished him to foretell events, watched for the hour of noon, when he was in the habit of coming up to the island of Pharos, with Poseidon’s flock of seals, which he tended at the bottom of the sea. Surrounded by these creatures of the deep, he used to slumber beneath the grateful shade of the rocks. This was the favourable moment to seize the prophet, who, in order to avoid importunities, would change himself into an infinite variety of forms. But patience gained the day; for if he were only held long enough, he became wearied at last, and, resuming his true form, gave the information desired, after which he dived down again to the bottom of the sea, accompanied by the animals he tended.

Triton And The Tritons

Triton was the only son of Poseidon and Amphitrite, but he possessed little influence, being altogether a minor divinity. He is usually represented as preceding his father and acting as his trumpeter, using a conch-shell for this purpose. He lived with his parents in their beautiful golden palace beneath the sea at AEgea, and his favourite pastime was to ride over the billows on horses or sea-monsters. Triton is always represented as half man, half fish, the body below the waist terminating in the tail of a dolphin. We frequently find mention of Tritons who are either the offspring or kindred of Triton.

Glaucus

Glaucus is said to have become a sea-divinity in the following manner. While angling one day, he observed that the fish he caught and threw on the bank, at once nibbled at the grass and then leaped back into the water. His curiosity was naturally excited, and he proceeded to gratify it by taking up a few blades and tasting them. No sooner was this done than, obeying an irresistible impulse, he precipitated himself into the deep, and became a sea-god.

Like most sea-divinities he was gifted with prophetic power, and each year visited all the islands and coasts with a train of marine monsters, foretelling all kinds of evil. Hence fishermen dreaded his approach, and endeavoured, by prayer and fasting, to avert the misfortunes which he prophesied. He is often represented floating on the billows, his body covered with mussels, sea-weed, and shells, wearing a full beard and long flowing hair, and bitterly bewailing his immortality.

Thetis

The silver-footed, fair-haired Thetis, who plays an important part in the mythology of Greece, was the daughter of Nereus, or, as some assert, of Poseidon. Her grace and beauty were so remarkable that Zeus and Poseidon both sought an alliance with her; but, as it had been foretold that a son of hers would gain supremacy over his father, they relinquished their intentions, and she became the wife of Peleus, son of AEacus. Like Proteus, Thetis possessed the power of transforming herself into a variety of different shapes, and when wooed by Peleus she exerted this power in order to elude him. But, knowing that persistence would eventually succeed, he held her fast until she assumed her true form. Their nuptials were celebrated with the utmost pomp and magnificence, and were honoured by the presence of all the gods and goddesses, with the exception of Eris. How the goddess of discord resented her exclusion from the marriage festivities has already been shown.

Thetis ever retained great influence over the mighty lord of heaven, which, as we shall see hereafter, she used in favour of her renowned son, Achilles, in the Trojan War.

When Halcyone plunged into the sea in despair after the shipwreck and death of her husband King Ceyx, Thetis transformed both husband and wife into the birds called kingfishers (halcyones), which, with the tender affection which characterized the unfortunate couple, always fly in pairs. The idea of the ancients was that these birds brought forth their young in nests, which float on the surface of the sea in calm weather, before and after the shortest day, when Thetis was said to keep the waters smooth and tranquil for their especial benefit; hence the term “halcyon-days,” which signifies a period of rest and untroubled felicity.

Thaumas, Phorcys And Ceto

The early Greeks, with their extraordinary power of personifying all and every attribute of Nature, gave a distinct personality to those mighty wonders of the deep, which, in all ages, have afforded matter of speculation to educated and uneducated alike. Among these personifications we find Thaumas, Phorcys, and their sister Ceto, who were the offspring of Pontus.

Thaumas (whose name signifies Wonder) typifies that peculiar, translucent condition of the surface of the sea when it reflects, mirror-like, various images, and appears to hold in its transparent embrace the flaming stars and illuminated cities, which are so frequently reflected on its glassy bosom.

Thaumas married the lovely Electra (whose name signifies the sparkling light produced by electricity), daughter of Oceanus. Her amber-coloured hair was of such rare beauty that none of her fair-haired sisters could compare with her, and when she wept, her tears, being too precious to be lost, formed drops of shining amber.

Phorcys and Ceto personified more especially the hidden perils and terrors of the ocean. They were the parents of the Gorgons, the Graea, and the Dragon which guarded the golden apples of the Hesperides.

Leucothea

Leucothea was originally a mortal named Ino, daughter of Cadmus, king of Thebes. She married Athamas, king of Orchomenus, who, incensed at her unnatural conduct to her step-children, pursued her and her son to the sea-shore, when, seeing no hope of escape, she flung herself with her child into the deep. They were kindly received by the Nereides, and became sea-divinities under the name of Leucothea and Palaemon.

The Sirens

The Sirens would appear to have been personifications of those numerous rocks and unseen dangers, which abound on the S.W. coast of Italy. They were sea-nymphs, with the upper part of the body that of a maiden and the lower that of a sea-bird, having wings attached to their shoulders, and were endowed with such wonderful voices, that their sweet songs are said to have lured mariners to destruction.

Ares (Mars)

Ares, the son of Zeus and Hera, was the god of war, who gloried in strife for its own sake; he loved the tumult and havoc of the battlefield, and delighted in slaughter and extermination; in fact he presents no benevolent aspect which could possibly react favourably upon human life.

Epic poets, in particular, represent the god of battles as a wild ungovernable warrior, who passes through the armies like a whirlwind, hurling to the ground the brave and cowardly alike; destroying chariots and helmets, and triumphing over the terrible desolation which he produces.

In all the myths concerning Ares, his sister Athene ever appears in opposition to him, endeavouring by every means in her power to defeat his bloodthirsty designs. Thus she assists the divine hero Diomedes at the siege of Troy, to overcome Ares in battle, and so well does he profit by her timely aid, that he succeeds in wounding the sanguinary war-god, who makes his exit from the field, roaring like ten thousand bulls.

Ares appears to have been an object of aversion to all the gods of Olympus, Aphrodite alone excepted. As the son of Hera, he had inherited from his mother the strongest feelings of independence and contradiction, and as he took delight in upsetting that peaceful course of state-life which it was pre-eminently the care of Zeus to establish, he was naturally disliked and even hated by him.

When wounded by Diomedes, as above related, he complains to his father, but receives no sympathy from the otherwise kindly and beneficent ruler of Olympus, who thus angrily addresses him: “Do not trouble me with thy complaints, thou who art of all the gods of Olympus most hateful to me, for thou delightest in nought save war and strife. The very spirit of thy mother lives in thee, and wert thou not my son, long ago wouldst thou have lain deeper down in the bowels of the earth than the son of Uranus.”

Ares, upon one occasion, incurred the anger of Poseidon by slaying his son Halirrhothios, who had insulted Alcippe, the daughter of the war-god. For this deed, Poseidon summoned Ares to appear before the tribunal of the Olympic gods, which was held upon a hill in Athens. Ares was acquitted, and this event is supposed to have given rise to the name Areopagus (or Hill of Ares), which afterwards became so famous as a court of justice. In the Gigantomachia, Ares was defeated by the Aloidae, the two giant-sons of Poseidon, who put him in chains, and kept him in prison for thirteen months.

Ares is represented as a man of youthful appearance; his tall muscular form combines great strength with wonderful agility. In his right hand he bears a sword or a mighty lance, while on the left arm he carries his round shield (see next page). His demoniacal surroundings are Terror and Fear; Enyo, the goddess of the war-cry; Keidomos, the demon of the noise of battles; and Eris (Contention), his twin-sister and companion, who always precedes his chariot when he rushes to the fight, the latter being evidently a simile of the poets to express the fact that war follows contention.

Eris is represented as a woman of florid complexion, with dishevelled hair, and her whole appearance angry and menacing. In one hand she brandishes a poniard and a hissing adder, whilst in the other she carries a burning torch. Her dress is torn and disorderly, and her hair intertwined with venomous snakes. This divinity was never invoked by mortals, except when they desired her assistance for the accomplishment of evil purposes.

Mars

The Roman divinity most closely resembling the Greek Ares, and identified with him, was called Mars, Mamers, and Marspiter or Father Mars.

The earliest Italian tribes, who were mostly engaged in the pursuit of husbandry, regarded this deity more especially as the god of spring, who vanquished the powers of winter, and encouraged the peaceful arts of agriculture. But with the Romans, who were an essentially warlike nation, Mars gradually loses his peaceful character, and, as god of war, attains, after Jupiter, the highest position among the Olympic gods. The Romans looked upon him as their special protector, and declared him to have been the father of Romulus and Remus, the founders of their city. But although he was especially worshipped in Rome as god of war, he still continued to preside over agriculture, and was also the protecting deity who watched over the welfare of the state.

As the god who strode with warlike step to the battlefield, he was called Gradivus (from gradus, a step), it being popularly believed by the Romans that he himself marched before them to battle, and acted as their invisible protector. As the presiding deity over agriculture, he was styled Sylvanus, whilst in his character as guardian of the state, he bore the name of Quirinus.

The priests of Mars were twelve in number, and were called Salii, or the dancers, from the fact that sacred dances, in full armour, formed an important item in their peculiar ceremonial. This religious order, the members of which were always chosen from the noblest families in Rome, was first instituted by Numa Pompilius, who intrusted to their special charge the Anciliae, or sacred shields. It is said that one morning, when Numa was imploring the protection of Jupiter for the newly-founded city of Rome, the god of heaven, as though in answer to his prayer, sent down an oblong brazen shield, and, as it fell at the feet of the king, a voice was heard announcing that on its preservation depended the future safety and prosperity of Rome. In order, therefore, to lessen the chances of this sacred treasure being abstracted, Numa caused eleven more to be made exactly like it, which were then given into the care of the Salii.

The assistance and protection of the god of war was always solemnly invoked before the departure of a Roman army for the field of battle, and any reverses of fortune were invariably ascribed to his anger, which was accordingly propitiated by means of extraordinary sin-offerings and prayers.

In Rome a field, called the Campus Martius, was dedicated to Mars. It was a large, open space, in which armies were collected and reviewed, general assemblies of the people held, and the young nobility trained to martial exercises.

The most celebrated and magnificent of the numerous temples built by the Romans in honour of this deity was the one erected by Augustus in the Forum, to commemorate the overthrow of the murderers of Caesar.

Of all existing statues of Mars the most renowned is that in the Villa Ludovisi at Rome, in which he is represented as a powerful, muscular man in the full vigour of youth. The attitude is that of thoughtful repose, but the short, curly hair, dilated nostrils, and strongly marked features leave no doubt as to the force and turbulence of his character. At his feet, the sculptor has placed the little god of love, who looks up all undaunted at the mighty war-god, as though mischievously conscious that this unusually quiet mood is attributable to his influence.

Religious festivals in honour of Mars were generally held in the month of March; but he had also a festival on the Ides of October, when chariot-races took place, after which, the right-hand horse of the team which had drawn the victorious chariot, was sacrificed to him. In ancient times, human sacrifices, more especially prisoners of war, were offered to him; but, at a later period, this cruel practice was discontinued.

The attributes of this divinity are the helmet, shield, and spear. The animals consecrated to him were the wolf, horse, vulture, and woodpecker.

Intimately associated with Mars in his character as god of war, was a goddess called Bellona, who was evidently the female divinity of battle with one or other of the primitive nations of Italy (most probably the Sabines), and is usually seen accompanying Mars, whose war-chariot she guides. Bellona appears on the battle-field, inspired with mad rage, cruelty, and the love of extermination. She is in full armour, her hair is dishevelled, and she bears a scourge in one hand, and a lance in the other.

A temple was erected to her on the Campus Martius. Before the entrance to this edifice stood a pillar, over which a spear was thrown when war was publicly declared.

Nike (Victoria)

Nike, the goddess of victory, was the daughter of the Titan Pallas, and of Styx, the presiding nymph of the river of that name in the lower world.

In her statues, Nike somewhat resembles Athene, but may easily be recognized by her large, graceful wings and flowing drapery, which is negligently fastened on the right shoulder, and only partially conceals her lovely form. In her left hand, she holds aloft a crown of laurel, and in the right, a palm-branch. In ancient sculpture, Nike is usually represented in connection with colossal statues of Zeus or Pallas-Athene, in which case she is life-sized, and stands on a ball, held in the open palm of the deity she accompanies. Sometimes she is represented engaged in inscribing the victory of a conqueror on his shield, her right foot being slightly raised and placed on a ball.

A celebrated temple was erected to this divinity on the Acropolis at Athens, which is still to be seen, and is in excellent preservation.

Victoria

Under the name of Victoria, Nike was highly honoured by the Romans, with whom love of conquest was an all-absorbing characteristic. There were several sanctuaries in Rome dedicated to her, the principal of which was on the Capitol, where it was the custom of generals, after success had attended their arms, to erect statues of the goddess in commemoration of their victories. The most magnificent of these statues, was that raised by Augustus after the battle of Actium. A festival was celebrated in honour of Nike on the 12th of April.

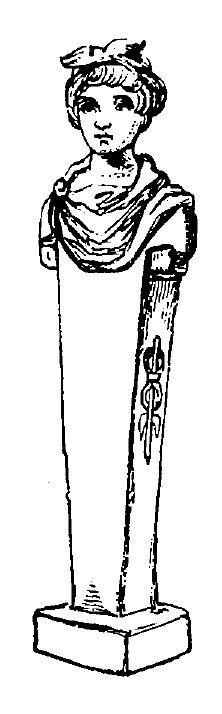

Hermes (Mercury)

Hermes was the swift-footed messenger, and trusted ambassador of all the gods, and conductor of shades to Hades. He presided over the rearing and education of the young, and encouraged gymnastic exercises and athletic pursuits, for which reason, all gymnasiums and wrestling schools throughout Greece were adorned with his statues. He is said to have invented the alphabet, and to have taught the art of interpreting foreign languages, and his versatility, sagacity, and cunning were so extraordinary, that Zeus invariably chose him as his attendant, when, disguised as a mortal, he journeyed on earth.

Hermes was worshipped as god of eloquence, most probably from the fact that, in his office as ambassador, this faculty was indispensable to the successful issue of the negotiations with which he was intrusted. He was regarded as the god who granted increase and prosperity to flocks and herds, and, on this account, was worshipped with special veneration by herdsmen.

In ancient times, trade was conducted chiefly by means of the exchange of cattle. Hermes, therefore, as god of herdsmen, came to be regarded as the protector of merchants, and, as ready wit and adroitness are valuable qualities both in buying and selling, he was also looked upon as the patron of artifice and cunning. Indeed, so deeply was this notion rooted in the minds of the Greek people, that he was popularly believed to be also god of thieves, and of all persons who live by their wits.

As the patron of commerce, Hermes was naturally supposed to be the promoter of intercourse among nations; hence, he is essentially the god of travellers, over whose safety he presided, and he severely punished those who refused assistance to the lost or weary wayfarer. He was also guardian of streets and roads, and his statues, called Hermae (which were pillars of stone surmounted by a head of Hermes), were placed at cross-roads, and frequently in streets and public squares.

Being the god of all undertakings in which gain was a feature, he was worshipped as the giver of wealth and good luck, and any unexpected stroke of fortune was attributed to his influence. He also presided over the game of dice, in which he is said to have been instructed by Apollo.

Hermes was the son of Zeus and Maia, the eldest and most beautiful of the seven Pleiades (daughters of Atlas), and was born in a cave of Mount Cyllene in Arcadia. As a mere babe, he exhibited an extraordinary faculty for cunning and dissimulation; in fact, he was a thief from his cradle, for, not many hours after his birth, we find him creeping stealthily out of the cave in which he was born, in order to steal some oxen belonging to his brother Apollo, who was at this time feeding the flocks of Admetus. But he had not proceeded very far on his expedition before he found a tortoise, which he killed, and, stretching seven strings across the empty shell, invented a lyre, upon which he at once began to play with exquisite skill. When he had sufficiently amused himself with the instrument, he placed it in his cradle, and then resumed his journey to Pieria, where the cattle of Admetus were grazing. Arriving at sunset at his destination, he succeeded in separating fifty oxen from his brother’s herd, which he now drove before him, taking the precaution to cover his feet with sandals made of twigs of myrtle, in order to escape detection. But the little rogue was not unobserved, for the theft had been witnessed by an old shepherd named Battus, who was tending the flocks of Neleus, king of Pylos (father of Nestor). Hermes, frightened at being discovered, bribed him with the finest cow in the herd not to betray him, and Battus promised to keep the secret. But Hermes, astute as he was dishonest, determined to test the shepherd’s integrity. Feigning to go away, he assumed the form of Admetus, and then returning to the spot offered the old man two of his best oxen if he would disclose the author of the theft. The ruse succeeded, for the avaricious shepherd, unable to resist the tempting bait, gave the desired information, upon which Hermes, exerting his divine power, changed him into a lump of touchstone, as a punishment for his treachery and avarice. Hermes now killed two of the oxen, which he sacrificed to himself and the other gods, concealing the remainder in the cave. He then carefully extinguished the fire, and, after throwing his twig shoes into the river Alpheus, returned to Cyllene.

Apollo, by means of his all-seeing power, soon discovered who it was that had robbed him, and hastening to Cyllene, demanded restitution of his property. On his complaining to Maia of her son’s conduct, she pointed to the innocent babe then lying, apparently fast asleep, in his cradle, whereupon, Apollo angrily aroused the pretended sleeper, and charged him with the theft; but the child stoutly denied all knowledge of it, and so cleverly did he play his part, that he even inquired in the most naive manner what sort of animals cows were. Apollo threatened to throw him into Tartarus if he would not confess the truth, but all to no purpose. At last, he seized the babe in his arms, and brought him into the presence of his august father, who was seated in the council chamber of the gods. Zeus listened to the charge made by Apollo, and then sternly desired Hermes to say where he had hidden the cattle. The child, who was still in swaddling-clothes, looked up bravely into his father’s face and said, “Now, do I look capable of driving away a herd of cattle; I, who was only born yesterday, and whose feet are much too soft and tender to tread in rough places? Until this moment, I lay in sweet sleep on my mother’s bosom, and have never even crossed the threshold of our dwelling. You know well that I am not guilty; but, if you wish, I will affirm it by the most solemn oaths.” As the child stood before him, looking the picture of innocence, Zeus could not refrain from smiling at his cleverness and cunning, but, being perfectly aware of his guilt, he commanded him to conduct Apollo to the cave where he had concealed the herd, and Hermes, seeing that further subterfuge was useless, unhesitatingly obeyed. But when the divine shepherd was about to drive his cattle back into Pieria, Hermes, as though by chance, touched the chords of his lyre. Hitherto Apollo had heard nothing but the music of his own three-stringed lyre and the syrinx, or Pan’s pipe, and, as he listened entranced to the delightful strains of this new instrument, his longing to possess it became so great, that he gladly offered the oxen in exchange, promising at the same time, to give Hermes full dominion over flocks and herds, as well as over horses, and all the wild animals of the woods and forests. The offer was accepted, and, a reconciliation being thus effected between the brothers, Hermes became henceforth god of herdsmen, whilst Apollo devoted himself enthusiastically to the art of music.

They now proceeded together to Olympus, where Apollo introduced Hermes as his chosen friend and companion, and, having made him swear by the Styx, that he would never steal his lyre or bow, nor invade his sanctuary at Delphi, he presented him with the Caduceus, or golden wand. This wand was surmounted by wings, and on presenting it to Hermes, Apollo informed him that it possessed the faculty of uniting in love, all beings divided by hate. Wishing to prove the truth of this assertion, Hermes threw it down between two snakes which were fighting, whereupon the angry combatants clasped each other in a loving embrace, and curling round the staff, remained ever after permanently attached to it. The wand itself typified power; the serpents, wisdom; and the wings, despatch - all qualities characteristic of a trustworthy ambassador.

The young god was now presented by his father with a winged silver cap (Petasus), and also with silver wings for his feet (Talaria), and was forthwith appointed herald of the gods, and conductor of shades to Hades, which office had hitherto been filled by Aïdes.

As messenger of the gods, we find him employed on all occasions requiring special skill, tact, or despatch. Thus he conducts Hera, Athene, and Aphrodite to Paris, leads Priam to Achilles to demand the body of Hector, binds Prometheus to Mount Caucasus, secures Ixion to the eternally revolving wheel, destroys Argus, the hundred-eyed guardian of Io, etc. etc.

As conductor of shades, Hermes was always invoked by the dying to grant them a safe and speedy passage across the Styx. He also possessed the power of bringing back departed spirits to the upper world, and was, therefore, the mediator between the living and the dead.

The poets relate many amusing stories of the youthful tricks played by this mischief-loving god upon the other immortals. For instance, he had the audacity to extract the Medusa’s head from the shield of Athene, which he playfully attached to the back of Hephaestus; he also stole the girdle of Aphrodite; deprived Artemis of her arrows, and Ares of his spear, but these acts were always performed with such graceful dexterity, combined with such perfect good humour, that even the gods and goddesses he thus provoked, were fain to pardon him, and he became a universal favourite with them all.

It is said that Hermes was one day flying over Athens, when, looking down into the city, he beheld a number of maidens returning in solemn procession from the temple of Pallas-Athene. Foremost among them was Herse, the beautiful daughter of king Cecrops, and Hermes was so struck with her exceeding loveliness that he determined to seek an interview with her. He accordingly presented himself at the royal palace, and begged her sister Agraulos to favour his suit; but, being of an avaricious turn of mind, she refused to do so without the payment of an enormous sum of money. It did not take the messenger of the gods long to obtain the means of fulfilling this condition, and he soon returned with a well-filled purse. But meanwhile Athene, to punish the cupidity of Agraulos, had caused the demon of envy to take possession of her, and the consequence was, that, being unable to contemplate the happiness of her sister, she sat down before the door, and resolutely refused to allow Hermes to enter. He tried every persuasion and blandishment in his power, but she still remained obstinate. At last, his patience being exhausted, he changed her into a mass of black stone, and, the obstacle to his wishes being removed, he succeeded in persuading Herse to become his wife.

In his statues, Hermes is represented as a beardless youth, with broad chest and graceful but muscular limbs; the face is handsome and intelligent, and a genial smile of kindly benevolence plays round the delicately chiselled lips.

As messenger of the gods he wears the Petasus and Talaria, and bears in his hand the Caduceus or herald’s staff.

As god of eloquence, he is often represented with chains of gold hanging from his lips, whilst, as the patron of merchants, he bears a purse in his hand.

The wonderful excavations in Olympia, to which allusion has already been made, have brought to light an exquisite marble group of Hermes and the infant Bacchus, by Praxiteles. In this great work of art, Hermes is represented as a young and handsome man, who is looking down kindly and affectionately at the child resting on his arm, but unfortunately nothing remains of the infant save the right hand, which is laid lovingly on the shoulder of his protector.

The sacrifices to Hermes consisted of incense, honey, cakes, pigs, and especially lambs and young goats. As god of eloquence, the tongues of animals were sacrificed to him.

Mercury

Mercury was the Roman god of commerce and gain. We find mention of a temple having been erected to him near the Circus Maximus as early as B.C. 495; and he had also a temple and a sacred fount near the Porta Capena. Magic powers were ascribed to the latter, and on the festival of Mercury, which took place on the 25th of May, it was the custom for merchants to sprinkle themselves and their merchandise with this holy water, in order to insure large profits from their wares.

The Fetiales (Roman priests whose duty it was to act as guardians of the public faith) refused to recognize the identity of Mercury with Hermes, and ordered him to be represented with a sacred branch as the emblem of peace, instead of the Caduceus. In later times, however, he was completely identified with the Greek Hermes.

Dionysus (Bacchus)

Dionysus, also called Bacchus (from bacca, berry), was the god of wine, and the personification of the blessings of Nature in general.

The worship of this divinity, which is supposed to have been introduced into Greece from Asia (in all probability from India), first took root in Thrace, whence it gradually spread into other parts of Greece.

Dionysus was the son of Zeus and Semele, and was snatched by Zeus from the devouring flames in which his mother perished, when he appeared to her in all the splendour of his divine glory. The motherless child was intrusted to the charge of Hermes, who conveyed him to Semele’s sister, Ino. But Hera, still implacable in her vengeance, visited Athamas, the husband of Ino, with madness, and the child’s life being no longer safe, he was transferred to the fostering care of the nymphs of Mount Nysa. An aged satyr named Silenus, the son of Pan, took upon himself the office of guardian and preceptor to the young god, who, in his turn, became much attached to his kind tutor; hence we see Silenus always figuring as one of the chief personages in the various expeditions of the wine-god.

Dionysus passed an innocent and uneventful childhood, roaming through the woods and forests, surrounded by nymphs, satyrs, and shepherds. During one of these rambles, he found a fruit growing wild, of a most refreshing and cooling nature. This was the vine, from which he subsequently learnt to extract a juice which formed a most exhilarating beverage. After his companions had partaken freely of it, they felt their whole being pervaded by an unwonted sense of pleasurable excitement, and gave full vent to their overflowing exuberance, by shouting, singing, and dancing. Their numbers were soon swelled by a crowd, eager to taste a beverage productive of such extraordinary results, and anxious to join in the worship of a divinity to whom they were indebted for this new enjoyment. Dionysus, on his part, seeing how agreeably his discovery had affected his immediate followers, resolved to extend the boon to mankind in general. He saw that wine, used in moderation, would enable man to enjoy a happier, and more sociable existence, and that, under its invigorating influence, the sorrowful might, for a while, forget their grief and the sick their pain. He accordingly gathered round him his zealous followers, and they set forth on their travels, planting the vine and teaching its cultivation wherever they went.

We now behold Dionysus at the head of a large army composed of men, women, fauns, and satyrs, all bearing in their hands the Thyrsus (a staff entwined with vine-branches surmounted by a fir-cone), and clashing together cymbals and other musical instruments. Seated in a chariot drawn by panthers, and accompanied by thousands of enthusiastic followers, Dionysus made a triumphal progress through Syria, Egypt, Arabia, India, etc., conquering all before him, founding cities, and establishing on every side a more civilized and sociable mode of life among the inhabitants of the various countries through which he passed.

When Dionysus returned to Greece from his Eastern expedition, he encountered great opposition from Lycurgus, king of Thrace, and Pentheus, king of Thebes. The former, highly disapproving of the wild revels which attended the worship of the wine-god, drove away his attendants, the nymphs of Nysa, from that sacred mountain, and so effectually intimidated Dionysus, that he precipitated himself into the sea, where he was received into the arms of the ocean-nymph, Thetis. But the impious king bitterly expiated his sacrilegious conduct. He was punished with the loss of his reason, and, during one of his mad paroxysms, killed his own son Dryas, whom he mistook for a vine.

Pentheus, king of Thebes, seeing his subjects so completely infatuated by the riotous worship of this new divinity, and fearing the demoralizing effects of the unseemly nocturnal orgies held in honour of the wine-god, strictly prohibited his people from taking any part in the wild Bacchanalian revels. Anxious to save him from the consequences of his impiety, Dionysus appeared to him under the form of a youth in the king’s train, and earnestly warned him to desist from his denunciations. But the well-meant admonition failed in its purpose, for Pentheus only became more incensed at this interference, and, commanding Dionysus to be cast into prison, caused the most cruel preparations to be made for his immediate execution. But the god soon freed himself from his ignoble confinement, for scarcely had his jailers departed, ere the prison-doors opened of themselves, and, bursting asunder his iron chains, he escaped to rejoin his devoted followers.

Meanwhile, the mother of the king and her sisters, inspired with Bacchanalian fury, had repaired to Mount Cithaeron, in order to join the worshippers of the wine-god in those dreadful orgies which were solemnized exclusively by women, and at which no man was allowed to be present. Enraged at finding his commands thus openly disregarded by the members of his own family, Pentheus resolved to witness for himself the excesses of which he had heard such terrible reports, and for this purpose, concealed himself behind a tree on Mount Cithaeron; but his hiding-place being discovered, he was dragged out by the half-maddened crew of Bacchantes and, horrible to relate, he was torn in pieces by his own mother Agave and her two sisters.

An incident which occurred to Dionysus on one of his travels has been a favourite subject with the classic poets. One day, as some Tyrrhenian pirates approached the shores of Greece, they beheld Dionysus, in the form of a beautiful youth, attired in radiant garments. Thinking to secure a rich prize, they seized him, bound him, and conveyed him on board their vessel, resolved to carry him with them to Asia and there sell him as a slave. But the fetters dropped from his limbs, and the pilot, who was the first to perceive the miracle, called upon his companions to restore the youth carefully to the spot whence they had taken him, assuring them that he was a god, and that adverse winds and storms would, in all probability, result from their impious conduct. But, refusing to part with their prisoner, they set sail for the open sea. Suddenly, to the alarm of all on board, the ship stood still, masts and sails were covered with clustering vines and wreaths of ivy-leaves, streams of fragrant wine inundated the vessel, and heavenly strains of music were heard around. The terrified crew, too late repentant, crowded round the pilot for protection, and entreated him to steer for the shore. But the hour of retribution had arrived. Dionysus assumed the form of a lion, whilst beside him appeared a bear, which, with a terrific roar, rushed upon the captain and tore him in pieces; the sailors, in an agony of terror, leaped overboard, and were changed into dolphins. The discreet and pious steersman was alone permitted to escape the fate of his companions, and to him Dionysus, who had resumed his true form, addressed words of kind and affectionate encouragement, and announced his name and dignity. They now set sail, and Dionysus desired the pilot to land him at the island of Naxos, where he found the lovely Ariadne, daughter of Minos, king of Crete. She had been abandoned by Theseus on this lonely spot, and, when Dionysus now beheld her, was lying fast asleep on a rock, worn out with sorrow and weeping. Wrapt in admiration, the god stood gazing at the beautiful vision before him, and when she at length unclosed her eyes, he revealed himself to her, and, in gentle tones, sought to banish her grief. Grateful for his kind sympathy, coming as it did at a moment when she had deemed herself forsaken and friendless, she gradually regained her former serenity, and, yielding to his entreaties, consented to become his wife.

Dionysus, having established his worship in various parts of the world, descended to the realm of shades in search of his ill-fated mother, whom he conducted to Olympus, where, under the name of Thyone, she was admitted into the assembly of the immortal gods.

Among the most noted worshippers of Dionysus was Midas, the wealthy king of Phrygia, the same who, as already related, gave judgment against Apollo. Upon one occasion Silenus, the preceptor and friend of Dionysus, being in an intoxicated condition, strayed into the rose-gardens of this monarch, where he was found by some of the king’s attendants, who bound him with roses and conducted him to the presence of their royal master. Midas treated the aged satyr with the greatest consideration, and, after entertaining him hospitably for ten days, led him back to Dionysus, who was so grateful for the kind attention shown to his old friend, that he offered to grant Midas any favour he chose to demand; whereupon the avaricious monarch, not content with his boundless wealth, and still thirsting for more, desired that everything he touched might turn to gold. The request was complied with in so literal a sense, that the now wretched Midas bitterly repented his folly and cupidity, for, when the pangs of hunger assailed him, and he essayed to appease his cravings, the food became gold ere he could swallow it; as he raised the cup of wine to his parched lips, the sparkling draught was changed into the metal he had so coveted, and when at length, wearied and faint, he stretched his aching frame on his hitherto luxurious couch, this also was transformed into the substance which had now become the curse of his existence. The despairing king at last implored the god to take back the fatal gift, and Dionysus, pitying his unhappy plight, desired him to bathe in the river Pactolus, a small stream in Lydia, in order to lose the power which had become the bane of his life. Midas joyfully obeying the injunction, was at once freed from the consequences of his avaricious demand, and from this time forth the sands of the river Pactolus have ever contained grains of gold.

Representations of Dionysus are of two kinds. According to the earliest conceptions, he appears as a grave and dignified man in the prime of life; his countenance is earnest, thoughtful, and benevolent; he wears a full beard, and is draped from head to foot in the garb of an Eastern monarch. But the sculptors of a later period represent him as a youth of singular beauty, though of somewhat effeminate appearance; the expression of the countenance is gentle and winning; the limbs are supple and gracefully moulded; and the hair, which is adorned by a wreath of vine or ivy leaves, falls over the shoulders in long curls. In one hand he bears the Thyrsus, and in the other a drinking-cup with two handles, these being his distinguishing attributes. He is often represented riding on a panther, or seated in a chariot drawn by lions, tigers, panthers, or lynxes.

Being the god of wine, which is calculated to promote sociability, he rarely appears alone, but is usually accompanied by Bacchantes, satyrs, and mountain-nymphs.

The finest modern representation of Ariadne is that by Danneker, at Frankfort-on-the-Maine. In this statue she appears riding on a panther; the beautiful upturned face inclines slightly over the left shoulder; the features are regular and finely cut, and a wreath of ivy-leaves encircles the well-shaped head. With her right hand she gracefully clasps the folds of drapery which fall away negligently from her rounded form, whilst the other rests lightly and caressingly on the head of the animal.

Dionysus was regarded as the patron of the drama, and at the state festival of the Dionysia, which was celebrated with great pomp in the city of Athens, dramatic entertainments took place in his honour, for which all the renowned Greek dramatists of antiquity composed their immortal tragedies and comedies.

He was also a prophetic divinity, and possessed oracles, the principal of which was that on Mount Rhodope in Thrace.

The tiger, lynx, panther, dolphin, serpent, and ass were sacred to this god. His favourite plants were the vine, ivy, laurel, and asphodel. His sacrifices consisted of goats, probably on account of their being destructive to vineyards.

Bacchus Or Liber

The Romans had a divinity called Liber who presided over vegetation, and was, on this account, identified with the Greek Dionysus, and worshipped under the name of Bacchus.

The festival of Liber, called the Liberalia, was celebrated on the 17th of March.