Evolution Revolution

Information in this chapter

Introduction

Webster’s dictionary defines communications as a process by which information is exchanged between individuals through a common system of symbols, signs, or behavior. It is commonly referred to as the exchange of information between parties. Few things are as essential in defining humanity as the process of communication. It knows only the boundaries that we place on it and is limited only by the extent to which we allow ourselves to freely dream and imagine. Human beings are a social species and as a result of our proclivity toward social interaction, we, like all social animals, seek to satisfy our need for social interaction by sharing with and learning new information from one another to benefit the species as a whole. It is a quality that has been imbued in man since his first appearance on Earth some 1.5 million years ago. This of course is not the result of accidental happenstance but rather the result of man’s development and maturity as a species.

Communication

The ability to harness individual and collective intellectual capital has aided humanity in ensuring its proliferation through the ages. As a result, modern man has surpassed his peer species, all of which are now long extinct and exist only in fossil records and anthropological archives. Modern man has ascended to a position of prominence in the world and this is in large part due to his ability to communicate effectively with his peers.

Psychology of Communication

Human beings communicate in a vast array of ways and for a variety of reasons. We possess an ever-growing and maturing arsenal from which we may draw the appropriate tool for conveying our messages. Often, the purpose behind our communication at its most basic level is to ensure our survival as a species, ward off loneliness by ensuring companionship, and promote information sharing. We have coveted the ability to communicate our thoughts and feelings since before the dawn of recorded history. This is evidenced in the work of anthropologists and archeologists the world over, who have discovered remnants of our collective past that suggest the evolution of modern communication from primitive nonverbal communication or visual communications depicting significant events taking place in the world surrounding these early people to modern verbal and written communication forms governed by lexemes and grammatical systems put in place to aid the synthesis and expression of our thoughts. Human communication is a marvel that has not been rivaled.

We cherish our ability to express our thoughts, our feelings, our hopes, our dreams, and our fears to one another. It is both freeing and reassuring to us on practical and esoteric levels. Regardless of one’s beliefs about the origins of mankind, one thing is certain: human beings remain socially predisposed to and actively seek out opportunities and media through which to express themselves. Throughout history, the mechanics of our communication have changed as has the sophistication involved. Man has seen extraordinary changes in how he communicates, from base, primitive forms of communication which have been depicted in Hollywood films to represent prehistoric man, to more elegant forms of communication that adopted structure and governance. Lexemes and grammatical rules came into existence and complemented other more “natural” forms of communication such as nonverbal and visual communication.

Early Forms of Communication

The development of communication first allowed man to capture his thoughts, ideas, dreams, fears, and hopes by the dim light of camp fires, and express them verbally and nonverbally. Later he learned more sophisticated forms of communication, such as pictographs. Pictographs are often associated with what anthropologists commonly refer to as the first Information Communication Revolution. During this first communication revolution, man’s primary forms of communication, the basic verbal and nonverbal, saw a quantum leap occur. By capturing his thoughts in written form in stone, man was able to preserve his ideas for future generations, regardless of its immobility (Figures 2.1 and 2.2).

Figure 2.1 Example of a cave pictograph at Gobustan, Azerbaijan.

Figure 2.2 Example of a cave pictograph at Lascaux, France.

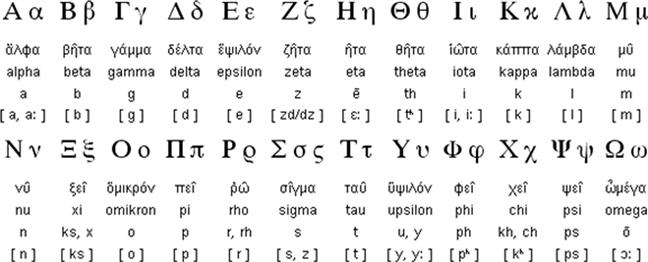

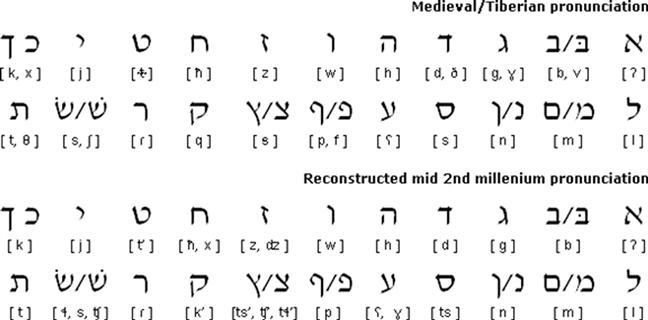

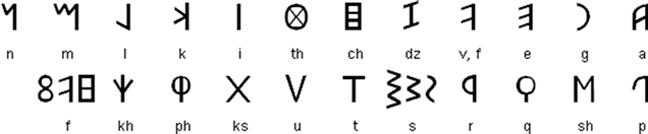

Later, as man evolved and matured, he began to develop and adopt more sophisticated forms of communication such as those governed by lexemes and grammatical structures; thus, the second communication revolution began. Though basic, these forms of written language and communication, appearing now on early forms of paper, papyrus, clay, wax, and other more portable media, paved the way for man’s ability to share and seek out new ideas and knowledge. Alphabets emerged and became common within geographic regions, allowing these forms of written communication to develop uniformity while also enabling their portability. As information began to traverse, the known world of ideas, concepts, theories, and philosophy also began to travel, crossing distances previously considered insurmountable (Figures 2.3–2.5).

Figure 2.3 Greek alphabet (Classical Attic pronunciation).

Figure 2.4 Hebrew alphabet (various pronunciations).

Figure 2.5 Archaic Etruscan alphabet (seventh to fifth centuries B.C.).

Later, around 1439, a German goldsmith and printer, Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg, more commonly known as Johannes Gutenberg, changed the world forever with his version of a mechanized, moveable printing press, as shown in Figure 2.6. Gutenberg’s contribution to the development of human communication is in many respects without equal as it allowed and made possible for the first time in human history large-scale production and replication of literary works which could thereby be translated from one language to another.

Figure 2.6 Gutenberg’s printing press.

Gutenberg created the printing press after a long period of time in the fifteenth century. Long after Gutenberg revolutionized communication technology by giving the world a movable, mechanized printing press came advancements in communications technology which would rival anything previously conceived by human beings and eclipse it in no uncertain terms. Communications researchers often refer to this era as being the third Information Communication Revolution, an era in which information could be transferred via controlled waves and electronic signals. During this era, Samuel F. B. Morse famously transmitted his message, “What hath God wrought?” from Washington to Baltimore on May 24, 1844, through his telegraph, changing forever the way in which human beings communicated. Not long thereafter, the world saw the birth of the telephone, a system of communication attributed to the culmination of the collective work of several individuals including but not limited to the following:

Advanced Telecommunications

The invention of the modern telephone and telecommunications networks changed forever the way in which human beings communicated. Though the written word is still considered a sacred and cherished element of our existence, the advent of the telephone has proved to be both an expeditious and convenient means by which to communicate both simple and complex thoughts and sentiments over initially short distances and later, much longer ones. Much later, in 1969, the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), later renamed Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA)—the name under which it currently operates today—developed an advanced computer network known as ARPAnet. Though rumors abound and incorrectly suggest that ARPAnet was developed and designed to provide a network that would ensure survivability in the event of global thermal nuclear war, reality suggests that what led to its development—though no one can deny there was and continues to be military interest in both the current and next generations of the Internet—was the desire of researchers who had become increasingly frustrated with the lack of large, supercomputing environments within the United States.1 ARPAnet would eventually mature into a series of networks including the National Sciences Foundations Network (NSFnet) and MILnet (Military Network), which would later give birth to the modern Internet, as we know it today. The invention of modern data and telecommunications networks such as the ones described above will eventually result in the death of distance. These networks will change forever how human beings communicate and continue to aid in the redefinition of how we communicate today.

Criminal Activity

An important question to ask with respect to our technological advancement, especially when considered in the context of this book, is what is the net effect of this technological explosion on criminality in general? And what impact has it demonstrated specifically in the realm of all things cyber? Certainly facts and anecdotal information can be cited, which articulate (historically) the emergence of abuse (in lock step fashion) with technological progression; however, we must still consider the potentially immoral results of the desire to adopt technological advances, irrespective of the costs.

There are no simple answers to these questions. However, exploring them and their implied consequence is a key to enabling today’s information security professionals, along with those of tomorrow, to actively identify and detect them in near or real time. This by no means is a trivial endeavor. Throughout history, mankind has seen the exploitation of technology and ideas, conceived for the betterment of all, for unlawful, illicit gain. It is a problem our ancestors faced and our descendents will wrestle with as well. Consequently, we must remain open and informed, to ensure the greatest degree of success in addressing these threats lest we be destined to experience similar ends. With respect to advanced technological solutions and their exploitation, one could argue that all modern electronic fraud and crime owe a debt of gratitude to forgery. In fact, a topic that is absolutely germane to the subject matter of this book, identifying theft, is a direct descendent of rudimentary forgery. Forgery can be defined simply as the process of producing, altering, or imitating objects, data points and statistics, and documentation with the express intent to deceive. Fraud, though similar to forgery, is the act of willfully committing a crime by deceiving another via the use of objects or data obtained through illicit means, typically including, but not limited to, the following:

Regardless of the means or the target of acquisition, it is the element of deceit via misrepresentation that must be given proper consideration when evaluating concepts such as forgery, fraud, deception, and theft as they relate to the subject matter of this book. These concepts are ubiquitous whether the perpetrator is running a strong-arm operation on the Jersey shore or administering a botnet with hundreds of thousands of hosts the world over.

Both law enforcement and the information security industry need to accept and understand this. Failing to do so in this day and age is nothing short of negligence. No longer can security professionals—whether operational, strategic, research-focused, or sales-driven—afford to imitate the three wise monkeys of the Toshogu shrine in Nikko, Japan2: seeing no evil, hearing no evil, and speaking no evil. There is simply too much at stake and too little to thwart the intentions that motivate gain by any means necessary. This, however, is not a new phenomenon. As soon as technologies associated with the first and second communications revolution began making appearances throughout the world in their earliest incarnations, the game was on.

Theft of Service

Though not the earliest form of exploitative compromise, wire-based fraud, defined as any criminally fraudulent activity that has been determined to involve electronic communications of any kind, at any phase of the event, remains popular today, just as it was in the early days of the Post Telegraph and Telephone (PTT) or the Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN). Today, in most books written on the subject matter of this one (regardless of how remote or close it may be), the authors almost always gravitate toward the low-hanging fruit of unlawful compromise of telecommunication carriers networks via alligator clips, rudimentary hacking of telecommunication switches after having first physically compromising them, or John Thomas Draper a.k.a. Cap’n Crunch and his experiments with tone emitting devices operating at 2600 Hz and beyond.3 Though all are important in the tapestry that would eventually be spun to include cybercrime and espionage, they do not represent a complete view.

In the late 1890s in Chicago, Illinois, one man saw the potential that lay within the PTT network for illicit gain. Jacob “Mont” Tennes,4 born on January 16, 1874 to German immigrants, liked to gamble. In fact, as Chicago legend has it, one day in the late 1890s he walked onto State Street, stumbled upon a floating craps game and left it with $3800.00. According to legend, Tennes returned two days later, doubled his winnings, and left promptly. In 1898, he used the money and opened up a saloon and billiard room that catered to the heirs of the Chicago gambling machine, the safe blowers, and confidence men; eventually Tennes invested in the earliest form of race wire service, a service used to provide intelligence regarding national horse races for illicit gains using PTT network technology.5 Mont Tennes and two of his brothers ran the early gambling and hand booking or “bookmaking” operations on Chicago’s north side. In 1904, Tennes and one of his brothers were indicted on bookmaking charges, found guilty, and ordered to pay $200.00 in fines, yet by 1909 Tennes was known as “the absolute dictator of race track gambling and handbooks in Chicago.”

In 1894, Carter Harrison II was elected mayor of Chicago and put an end to the handbook or bookmaking business altogether in and around horse tracks and racing. He was famously quoted as having said, “It is my intention to witness the sport of kings without the vice of kings.” For the next 18 years, there was no thoroughbred racing in Illinois. Gambling would go on, though, thanks to a new creation called the race wire. The race wire service was originally conceived by John Payne, a former telegraph operator from Cincinnati, Ohio, who, in the early 1900s, had worked for Western Union Telegraph Corporation. Payne’s system was clever and concise. He had devised a sound relay procedure for processing horse racing results. At the end of each race, Payne had a spotter at the racetrack who, using a mirror, would flash back a coded race result to a telegraph operator in a nearby building. On receipt, the telegrapher would immediately relay the results to handbooks also known as bookies, all over the city. He would soon establish his enterprise formally as the Payne Telegraph Service of Cincinnati.

In 1907, Tennes bought the “Payne System” exclusively for Illinois for $300 a day. He received the results at the Forest Park, Illinois train station on a switchboard consisting of a trunk line with 45 wires.

Codes were distributed to pool halls and bookies throughout Chicagoland and information flowed into the city of big shoulders from cities around the country regarding the race winners. The investment proved to be a profitable one for Tennes and as a result was the object of much dispute, debate, and violence over the years to come. In the 1920s, Tennes sold his race services to both the Torrio-Capone gang that ruled the city’s south side and the O’Banion gang that controlled its north side. Eventually the Tennes services were overtaken by more seasoned, modern, technologically sophisticated criminals and joined with wire services being brought west from New York. Ultimately, these wire services would stretch nationwide and see hundreds of millions of dollars generated well into the 1960s. Over time, these systems saw their usefulness and anonymity completely crumble. The systems were too well-known, too well-documented, and were becoming antiquated given the explosive popularity of PSTN. There was simply no way to stop the progressive growth and adoption of this emerging technology. As we mentioned earlier, although several authors have commented on the history of the exploitation of the PSTN and its predecessors, it is important to note and bear in mind that most commented with a modern “phreaker” or “hacker” visage in mind. The earliest parties who sought to compromise these networks, regardless of their reasons (personal use, criminal, or illicit gain), did so using what we would now consider “primitive” techniques. Their actions once again proved that technological progress and advancement do not blot the darker aspects of humanity, no matter what our predecessors or we would have liked to believe.

The same can be said of cases of criminal exploitation today. Never before has there been a time in human history when so much information, voluminous amounts of information the likes of which could never be contained in a library, has been available to so many at so little cost. If the renaissance period and the reformation symbolize two of the Western world’s greatest historic markers, then the advent of a deregulated Internet should not be far behind.

Summary

In this chapter, we have discussed communications from the earliest forms to the modern-day advancements in telecommunications. We have also discussed some of the leading founders and developers of the communication industry. It was important for us to lay out the entire spectrum and discuss the psychology of communications as it really paints a picture of the evolution of the criminal mind and how others started using technology for nefarious purposes. Lastly, as crime shifts from breaking physically into a building to copying documents and pictures, and listening to phone conversation as a primal way to gain all sorts of information, it has shifted to the cyber realm. With today’s advanced telecommunication infrastructure, a person no longer needs to be physically located at the target to steal information. The expansion of the telecommunication infrastructure to include Internet access has enabled cybercriminals to take advantage of stealing information without even being physically located at the target.

1 www.isoc.org/internet/history/brief.shtml http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ARPANET#History

2 In Japanese tradition, the three monkeys known as the “three wise monkeys” were Mirazu, who covered his eyes to see no evil; Kikazaru, who covered his ears to hear no evil; and Iwazaru, who covered his mouth to speak no evil. At times they are seen with a fourth monkey, Shizaru who symbolized the principle of “doing no evil”; he is often seen crossing his arms.

3 John Thomas Draper a.k.a. Cap’n Crunch was a legendary phone phreaker and progenitor of that area of research.

4 Jacob “Mont” Tennes was an early Chicago gambler and wire service operator, www.crimemagazine.com/history-race-wire-service