State-Sponsored Intelligence

Information in this chapter

Introduction

State-sponsored intelligence has played an integral role in establishing, managing, and retaining dominion since human beings first banded together in large, extended families, thousands of years ago, and began implementing social and geographic boundaries for themselves and their neighbors. History has shown this to be the case, and here, in the twenty-first century, state-sponsored intelligence is no less important or necessary. It is a very real part of our world, one which is not always easily understood but nevertheless imperative to our survival. It involves myriad differing actors, philosophies, methodologies, tools, techniques, and approaches. It is an ever-evolving discipline that sees cross-pollination among contributing entities within the state as pivotal to its success or failure and not open for discussion among the citizenry.

Within the world of state-sponsored intelligence careful consideration is given, but not limited, to the following influencers:

• Intelligence types to be gathered

• Intelligence gathering process

• Intelligence analysis process

• The negative repercussions of conducting state-sponsored intelligence gathering against a target

• Mechanisms for collection and submission of intelligence

• Categorization of intelligence

• Dissemination of intelligence once collected, analyzed, and corroborated

• The sources of the intelligence being acquired

• The degree of difficulty associated with corroborating the samples

• Socioeconomic stability of the nation and nations of interest (friendly or unfriendly) from which the intelligence is derived and to which it is related

• Foreign and international relations policy

• The implications of the intelligence for domestic and foreign concerns

• The potential threat vectors and points of confluence associated with preexisting intelligence and new samples

Much consideration must be given to the areas of operational, tactical, and strategic intelligence. The ability to differentiate and make intelligent decisions based on the information a given organization within a state receives is not trivial. In most respects, it is the culmination of the analysis and review of an immense amount of data and scenarios, some aspects of which were cultivated within academic environments, and removed from the grit of the field while others were cultivated, tested, and noted in the field.

Espionage and Its Influence on Next-Generation Threats

Espionage, in one form or other, has existed throughout the expanse of known, documented (and likely undocumented), human history. Examples of espionage use, development, endorsement, and adoption have been identified and noted in almost every culture of the world. Archeologists and anthropologists have found detailed accounts of such activity in countries such as Egypt, Samaria, Israel, Greece, Persia, Italy, China, Japan, Korea, India, and England; all of which endorsed the use of espionage unrepentantly in order to advance and achieve their agendas. This use ultimately culminated in the achievement or loss of their goals, goods, lands, and assets or life itself.

Within these cultures, the selection and training of practitioners of clandestine crafts was and remains a process shrouded in mystery. These agent provocateurs were carefully trained, in many cases, from birth or early childhood, in furtive disciplines in order that they become prepared for deployment when called on by their ranking authorities. Their missions would include intelligence gathering activities of a varied sort. Some involved infiltration via subversive means allowing the agent in question to operate in the open while in deep cover while others might be deployed in a manner that saw them involved in the propagation, dissemination, and proliferation of propaganda designed to undermine enemy opposition. Still others were deployed with a much simpler mission: to acquire data via any means necessary (in many cases often through seduction), and if need be carry out the mission to completion, utilization, or assassination. Often these activities would see operators deployed behind enemies’ lines in the heart of danger. The clandestine activities practiced by these agents have become the stuff of legends and for good reason. The missions undertaken by these actors in the ancient world just as in the modern one were passed down generationally.

They transitioned cultures, and political and military regimes feared and revered them at the same time.

Because of the economic and tactical value of their skills (supply and demand), these individuals often saw their services sought during times of peace in addition to times leading to and during war. As a result, they became targets of acquisition, viewed as essential to the individuals as well as the organizations that they served or opposed. Fundamental to their success was their knowledge of humanity—the motives that drive the ideological, economic, or primal aspects of humankind.

All were studied, mastered, and incorporated into their methodologies in order to increase field efficacy and garrison analysis. In striving for mastery of these aspects of human psychology in order to be better equipped to exploit when the time came, these agents strove for perfection in their craft. Risk mitigation or minimization was expected of them while deception and subversion became key to their tradecraft, along with the ability to acquire voluminous amounts of data in a variety of ways. This ability to retain information gathered for real or near real-time analysis (in addition to post collection analysis) would serve these agents well in making critical decisions while in the field. The ability to debrief safely and securely—via appropriate channels—became vital in their efforts and continues to be so. Finally, there was the ability to remain—figuratively and literally—silent until safely able to debrief with respect to the intelligence gathered through appropriate, secured channels.

Over time, through conflict—both public and private—these skills were practiced, refined, and proven in real-world situations, leading to the development of modern covert organizations such as the following:

1. United States Office of Naval Investigation (ONI)—the oldest continuously operating intelligence service in the nation. While its mission has taken many different forms over its evolution, the main purpose has not changed from its inception

2. United States Office of Strategic Services (OSS)—now known as the modern Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), developed during World War II

3. United States Armed Forces Security Agency (AFSA)—now known as the National Security Agency (NSA)

4. United Kingdom Ministry of Defence (MOD)—Defence Intelligence Staff (DIS)

5. United Kingdom Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ)

6. United Kingdom Secret Service (MI5)—responsible for counterintelligence (CI) and security

7. United Kingdom Secret Intelligence Service (SIS a.k.a. MI6) and Special Operations Executive (SOE)

8. Russian Glavnoye Razvedyvatel’noye Upravleniye (GRU) and Sluzhba Vneshney Razvedki (SVR), also known as the Foreign Intelligence Service

9. Chinese Ministry of State Security (MSS)—the Chinese government’s largest and most active foreign intelligence agency

10. Israeli Institute for Intelligence and Special Operation (Mossad or HaMossad)

11. Saudi Re’asat Al Istikhbarat Al A’amah (GIP)—now known as General Intelligence Presidency

12. North Korea Cabinet General Intelligence Bureau of the Korean Workers Party Central Committee (RDEI)—Research Department for External Intelligence and Liaison Department

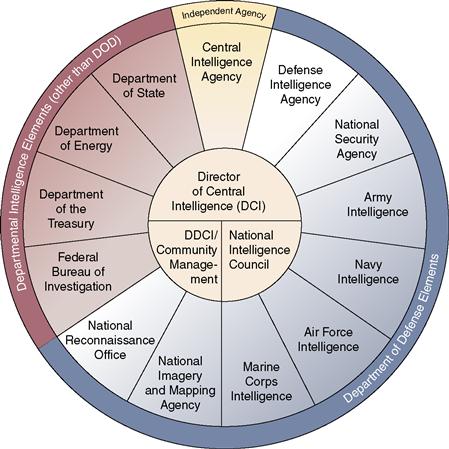

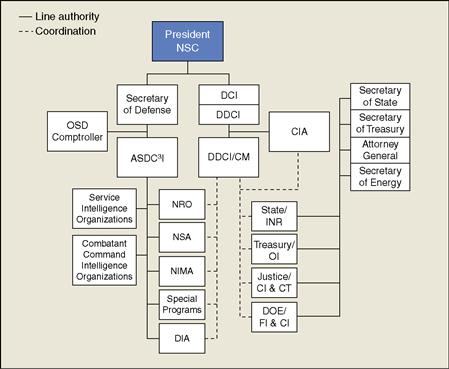

These organizations and others like them (nationally or subnationally sponsored), continue in the business of data and intelligence gathering for various purposes—some sensitive, some not; some classified, some not classified—all of which are relevant to their individual charters and areas of expertise. Unfortunately, they are not alone in their recognition of the value of data, information, and intelligence on the global stage. Nor were they the only organizations adept in plying like tradecraft for the express purpose of identifying and acquiring data, information, and intelligence (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 United States Intelligence Community as defined by the Federation of American Scientists.

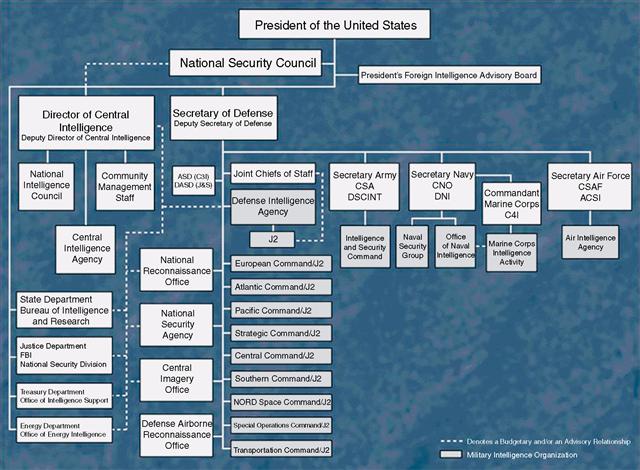

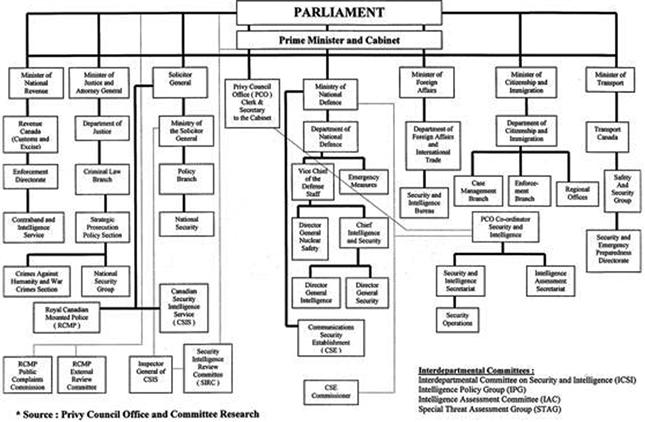

Criminal elements—whether localized geographically or internationally in scope—thrive, proliferate, and encourage criminal ecosystems gathering data, information, and intelligence and marketing its availability to the highest bidder. In Chapter 9, we explore and discuss more about these types of organizations and their activities as they relate to state and nonstate sponsored action in more detail. Often times, they are in direct opposition to organizations such as those mentioned before or against them in field. In some cases, former military and intelligence community operatives and officers the world over have elected to engage in underground enterprise adding a level of sophistication, professionalism, and cohesion not typical of traditional criminal organizations (Figures 6.2–6.6).

Figure 6.2 United States Intelligence Community insignias.

Figure 6.3 Mapping of Intelligence Community to the United States DNI.

Figure 6.4 Intelligence Community Structure.

Figure 6.5 United States Intelligence hierarchy.

Figure 6.6 British Parliament and Intelligence community mappings.

Intelligence Types

As we have seen, the desire to procure intelligence is as old as time. That desire has seen the evolution and birthing of formalized intelligence organizations some of which we have referred to above. However, it is important that we examine and classify intelligence in three easy-to-understand categories:

Let us begin by exploring the first concept, strategic intelligence. It is important to note that this is a simplification of what is not simple by any means. As such, it is a means by which to explain in an expeditious manner the roles that information and intelligence are given, our prioritization of them, and the subsequent use of the intelligence gathered to achieve our ends.

Strategic Intelligence

The etymology of the word strategy comes from the Greek strategia (generalship) and stategos. Strategy quite simply is the art and science of employing the political, economic, psychological, and military forces of a nation, or coalition of nations, to afford the maximum support in the adoption of policies that govern peace or war. Strategic intelligence focuses on broad issues which impact and direct strategy. For example, some of these issues may include but are not limited to the following:

3. Political assessments and assignments

4. Military capabilities and resources

The nature of this intelligence may be technical, scientific, diplomatic, sociological, or any combination thereof. These types of intelligence are analyzed in concert with known information pertaining to the data related to the area in question (e.g., geographic, demographic, and industrial capacities). This information provides a great deal of insight that feeds other intelligence operations and organizations serviced by them.

Tactical Intelligence

Tactical intelligence is focused on support to operations at the tactical level, and would be attached to the Battlegroup. Specialized units operating in reconnaissance capacities carry out the mission to identify, observe, and collect data that will later be delivered to command elements for dissemination to command elements and units. At the tactical level, briefings are then delivered to patrols on current threats and collection priorities; these patrols are then debriefed to elicit information for analysis and communication through the reporting chain. Those with command responsibilities and decision-making power often influence tactical intelligence initiatives, as a part of strategic intelligence agendas. This is a critical concept to grasp hold of and one that is not only ubiquitous but also crucial to the agendas set forth by nation states and their military and intelligence communities.

Operational Intelligence

Operational intelligence (OPINTEL) is a form of data acquisition considered necessary to both intelligence community and military organizations for the successful planning, execution, and accomplishment of missions (tactical and/or strategic), and operations and campaigns within geotheaters and areas of operation—sanctioned and unsanctioned. OPINTEL is focused on providing support to an expeditionary force commander and is traditionally seen attached to headquarters units. This is critical as it feeds into and supports activity associated with strategic and tactical intelligence initiatives. It should not be confused with the activities associated with business process management (sometimes referred to as OPINTEL), which focuses on providing real-time monitoring of business processes and activities as they are executed within enterprise business computer systems.

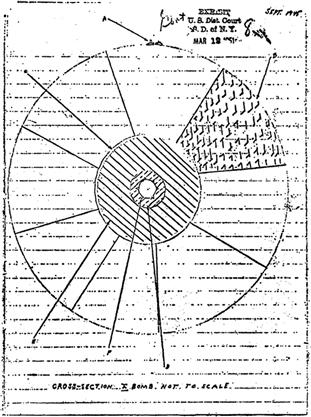

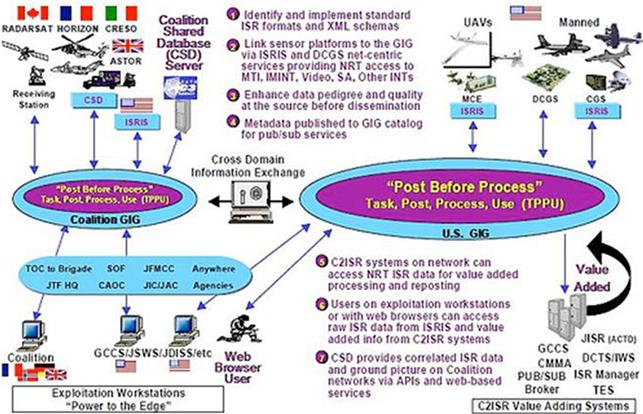

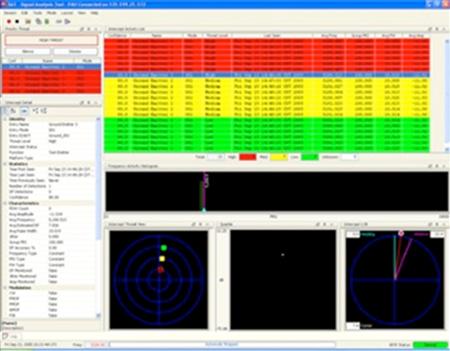

OPINTEL utilizes Electronic Intelligence (ELINT) among other forms of intelligence gathering mechanisms to identify, gather, and ensure the secure transmission of data from operators to analysts, ultimately arriving in the hands of decision-makers tasked with command responsibilities. ELINT is a form of intelligence that focuses on the interception of noncommunication signals transmitted over electromagnetic waves with the exception being those identified as originating from atomic or nuclear detonations. Nonelectromagnetic transmissions such as those originating in atomic or nuclear detonation fall into the realm of MASINT (Measurement and Signal Intelligence). ELINT saw its birth during World War II in which Allied forces monitored Axis air defense radar systems in order to neutralize them during a bombing raid via direct strikes or electronic countermeasures (Figure 6.7).

Figure 6.7 Data collected during a MASINT operation.

Over time, this practice has continued in other conflicts, in which the United States has been involved, involving the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), and the People’s Republic of China during the Cold War, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (also known as North Vietnam) during the war in Southeast Asia, and in conflicts the world over involving Libya, Iran, and more current conflicts in the middle east. Although it is easy to mistake ELINT for RADINT (Radar Intelligence), RADINT does not involve the interception of radar signals but rather focuses on flight path intelligence and other data specifics derived from the reflection of enemy radar signals. RADINT by virtue of categorical relation is a subset of MASINT. ELINT itself contains the following subcategories:

FISINT focuses on identifying and tracking signals transmitted by foreign entities when testing and deploying new technology in aerospace, surface, and subsurface systems such as tracking and aiming signals and video links. TELINT, which is considered a subcategory of the subcategory that is FISINT, is the process of taking measurements from a remote location and transmitting those measurements to receiving equipment. There are ample applications of telemetry in both the civilian and defense industrial base. Examples of the former may include a power company’s use of radio signals from remote power lines to relay operational information to an intelligence center within the power grid. Examples of the latter may include the use of signals to relay performance and operational information on munitions and smart weapons.

ELINT is an integral aspect of over-arching intelligence processes seen within state sponsored intelligence activity (Figure 6.8).

Figure 6.8 Rockwell Collins ELINT PULSE ANALYZER (PAU)/CS-3001.

Traditional Forms of Intelligence Gathering

Within the sphere of information and intelligence gathering, some techniques have remained unchanged. Simply stated, there was no need to fix what was not broken. Techniques and methodologies of this sort have transcended time, space, culture, and borders as we have described previously largely because of the stagnation in development seen in humanity. The who, what, where, when, how, and whys are all as important today as they were 7000 years ago although the targets and information may have changed as has the reasoning behind the activity in general. Regardless of this, the underlying theme for this type of activity is the need to know, versus the desire to know.

At its core, this is rooted in the ability to manage and control the balance of power within a given contextual model. This is a human issue, which can only be addressed by humans. As a result, field craft, or the tools and methodology of the trade, have been developed to guard against the probing activities of unauthorized parties, or perform these activities without being detected. Failure or success is often predicated on two factors being mastered with respect to this space: deception and subversion. Why are these concepts so important to these activities? For many reasons, however, depending on the context in which one finds oneself, they may mean the difference between life and death. Being able to extract or remove oneself and/or team with the target of interest in hand and without incurring notice is key in all intelligence operations, electronic or otherwise. To be caught in the act is a typically unacceptable option in most cases. Equally, valuable to the success or failure of these activities was the ability to remain silent under the most inhospitable of circumstances as well as in hospitable ones.

Divulging data to anyone other than authorized personnel is an anathema to parties actively engaged in this type of work. As we discussed earlier, we have seen the continued evolution of these two tactics and techniques in addition to the evolution of associated processes. The continued evolution, creation, execution, and implementation of these processes in practice and theory are paramount to intelligence gathering. In modern times, we have seen continued innovation; creation and implementation appear in four primary areas of information and intelligence gathering. The four major methods for information gathering are as follows:

Human Source Intelligence (HUMINT) is a method focused on the identification, compromise, and use of human beings via interpersonal contact for the purpose of gaining valuable intelligence. It is also often utilized for CI. CI refers to efforts made by intelligence, military, and subnational organizations to prevent hostile or enemy intelligence organizations from successfully identifying, gathering, collecting, and analyzing intelligence against them or their allies. It is important to understand that for HUMINT to be most effective, it is necessary to know the target from which the information is to be obtained. This requires either the exploitation of a preexistent relationship or the creation of a relationship for the express purpose of extracting information.

Though it sounds exploitative in nature, it is a vital element tool in information gathering and collecting. HUMINT is extremely effective and at times a dangerous proposition. It requires great care for the well-being of the operative and informant at all times.

This requires that, during the process of trust building, the informant feels safe and reciprocates his or her level of trust with the operative in kind. Although it sounds disagreeable, it is again, within the context of the process of information and intelligence gathering, a well-proven technique with an equally impressive record of success. There are several reasons for its success, however; the basis for the greatest degrees of success seen within this process is the establishment of trust as mentioned previously, between operator and informant.

Equally important to establishing and preserving trust is first being able to identify a target of opportunity from which to begin the building of trust in order to successfully extract information and intelligence. This requires reconnaissance or special surveillance work to be done well in advance, taking into consideration a variety of details about the subject in question and his or her social networks. In many cases, targets or subjects of interest represent and demonstrate an array of characteristics:

1. The willing, friendly, and witting participants

2. The unwilling, unfriendly, and hostile or unwitting participants

Tradition dictates that targets or subjects of opportunity may include human beings working in one or more of the following capacities:

1. Foreign Internal Defense (FID) personnel (e.g., those working with host nation forces or populations in diplomatic or official capacities)

2. Official Advisors or those working in advisory capacities within foreign service or state department roles

3. Diplomats or those holding diplomatic assignments and responsibilities

4. Espionage agents or clandestine operatives

5. Military attachés and/or embassy personnel

6. Nongovernmental organizations or subnational entities

7. Prisoners of war or officially held detainees

9. Routine or specialized military patrols in occupied territory or behind enemy lines

10. Special operations teams operating in occupied territory or behind enemy lines

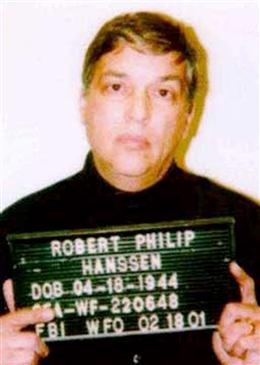

We next begin reviewing some key cases where HUMINT techniques and tactics have leveraged successfully with catastrophic ends. We focus on four cases of recent historical importance to the people and government of the United States of America. You will notice that in these cases HUMINT was paramount to the successful compromise of these operatives—all of whom betrayed their country and obligations.

Code Breaking or Cryptanalysis (COMINT/SIGINT)

Codes and their use are, like espionage, well-represented and historically prevalent. Cryptography as an art and science is anything but new. Examine the etymology of the word and you will see quite quickly (and clearly), that it is the science of codes and originated from the Greek words kryptos (secret) and graphos (writing). Historical examples abound from Lysander of the Spartans to Julius Caesar. After the fall of Rome in 472 A.D., it was not until Italian and French cryptographers in the 1500s initiated the resurrection of the art and science of cryptography that it emerged with extremely complex codes and ciphers never previously seen or used. The Science of breaking these codes became known as cryptanalysis. Once begun, it has continued to grow, maturing as a discipline with the advent of new, more complex ciphers and mathematical models.

In modern times, code breaking as well as cryptanalysis is largely dependent on the interception of signals or messages between people (e.g., COMINT or communications intelligence), or between machines and/or networks (e.g., ELINT) or a combination of the two. Regardless of how the data are gathered, the resultant analysis is often as complex as it is thorough. Many cases see analysis being conducted on data deemed “nonsensitive” and “sensitive” with more effort often associated with analyzing “sensitive” data. Analysis of traffic will occur—in real or near real-time packet captures or streamed packet captures—whether the traffic can be decrypted or not.

Aircraft or Satellite Photography (IMINT)

Since the advent of flight, the value of aerial photographs has been realized and recognized as being integral to information and intelligence gathering initiatives of various types. Whether for purposes of espionage, defense, or other state or federally sponsored initiatives, the value demonstrated by aerial photography proved extremely relevant and important historically during times of peace and war. As science and the aerospace industry matured bringing to market advanced satellite technologies, so too did the accuracy and resonance of aerial intelligence acquisition. Today, this is still the case; however, almost anyone has access to basic satellite imagery via technology such as Google Maps and Google World.

Research in Open Publications (OSINT)

Sometimes referred to as Open Source Intelligence because of the use of publicly accessible information outlets and media sources, OSINT involves identifying, selecting, and acquiring information from publicly available sources while being able to analyze that data in order to produce actionable intelligence. It is important to bear in mind that there is no direct correlation to open source software, nor should there be any confusion to that end.

As these tactics evolved, becoming ubiquitous throughout the world via formal and informal organizations, their adoption as standardized forms of observation and information gathering pushed into the realm of the Internet and the cybercriminal arena. Given that in many cases, their use in traditional state sponsored and subnational intelligence operations is well-documented, it is likely that these trends will continue. As we have seen already, the desire to gain information or intelligence regardless of the purpose for doing so has long been a part of human existence and as such, techniques and threats have emerged to see that this information and intelligence gathering capability continues and flourishes.

Web Source Intelligence (WEBINT)

This is the ability to gather open information using the Internet. This can be done in various ways such as using Web crawlers and indexing systems to harvest just about any piece of content that is stored on publically available servers in any language. Additionally, this can also cross over into P2P networks, which are notorious for sharing very sensitive information. The purpose of utilizing WEBINT is performing deep Web collections that allow you to be very specific in what you are intending to gather. Verint is a company that provides WEBINT tools that have strong analytics to correlate unstructured data collections. Analysts who provide the needed intelligence on the specific sources on which they are currently working can use the output of the collection.

In summary, state sponsored intelligence gathering is and will continue as a silent vehicle of information gathering. With the rapid adoption and use of the Internet, it will only make it easier for Foreign Intelligence Services to gather data remotely by utilizing all facets of Web 2.0. Additionally, shifting of the next-generation workforce to a culture of sharing more personal information has shifted the traditional forms of espionage that are typically paid-for services to disclosing sensitive information based on principal.

Summary

In this chapter, we covered some very fundamental aspects of intelligence gathering. Foreign Intelligence Services are able to leverage economies of scale in order to gather information across many vectors that are not accessible to the general public. This provides them with very sensitive information that is worth a lot of money in the wrong the hands. As we articulated the various use cases around espionage, they just illustrate that certain people are willing to take life-changing risks in order to supply the enemy with information. Although these use cases are dealing with espionage, these same use cases can and often mirror the insider threat and corporate espionage we see in the private sector. In the private sector, employees are not vetted on the level of those serving various government agencies. The controls placed on data in the government are on a more need-to-know basis and typically most of their networks are not connected to the Internet, thereby making data exfiltration all that much harder, but it does happen. The key walk-away here is that a lot can be learned from these use cases as the world becomes more connected and your data sets become more disparate.