Cyber X

Criminal Syndicates, Nation States, Subnational Entities, and Beyond

Information in this chapter

Introduction

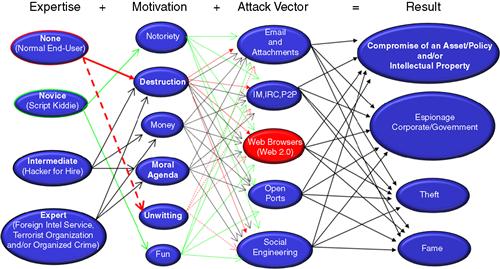

The classification and categorization of nefarious cyber actors has moved well past the script kiddie. Fame and bragging rights on compromised systems and Website defacements are so passé and had their 15 minutes of fame. It is important to realize that the motive behind the script kiddie or recreational hacker is a more ego-driven destruction of data without a hidden moral, political, or economic agenda. The entities that we are about to discuss are motivated by economic, political, and sometimes moral agendas that drive them to conduct targeted cyber operations from every corner of the globe. Figure 7.1 demonstrates some key characteristics of today’s cyber actor. If you asked 50 different security professionals in a room to classify cyber actors by expertise, motivation, and attack vector, you will get 50 different answers, but in the end, I think we can all agree with some of the factors shown in the figure. Additionally, the graphic really illustrates the multitude of attack vectors that are often leveraged depending on the skill set and expertise of the cyber actor.

Figure 7.1 Classification at a glance.

Classifying the Cyber Actor

The following is a brief description of the categories in Figure 7.1.

Expertise level:

1. None: This is your typical day-to-day end-user. In the eyes of the cyber actors, these are like pawns waiting to be compromised by a click of a button. Additionally, they might be patient zero and propagating exploit code without even knowing that they have been compromised. The flip side of this is the typical day-to-day end-user gone bad. A once trusted resource becoming an insider threat has the capability to destroy and exfiltrate critical intellectual property outside the premise of the organization.

2. Novice: These are your script kiddies, taking well-known methods of exploitation and hoping that the target of their attack is still vulnerable to the exploit. Additionally, the script kiddie ranks right up with the individuals who perform Web defacements or Distributed Denial of Service for fun or political agendas. In the greater scheme of things, those types of activities are loud, apparent, and easily corrected. This is not to say that experts are not going to use point-and-click prebuilt widely distributed attack frameworks. In some rare cases, script kiddie tools have been used to perform certain aspects of what we would categorize as an Advanced Persistent Threat. Point-and-click hacking can be found in exploit frameworks that are similar to that of metasploit or online “Hacking as a Service” (HaaS) tools in which individuals can rent/lease botnets and other types of attack tools. Additionally, these individuals might have high-level scripting and coding knowledge.

3. Intermediate: These are individuals with very specific skills sets that market themselves in the underground community and provide a wide range of services and capabilities for the money. There have been cases in which someone with these skill sets have performed activities based on moral and religious beliefs. These individuals have experience in writing code, low-level scripting language, and sometimes have the ability to rewrite or reverse certain aspects of code, depending on the target.

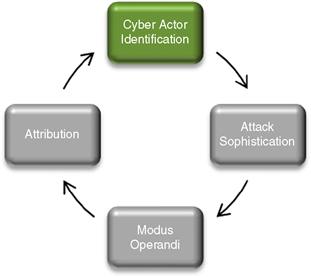

4. Expert: These are the most sophisticated cyber actors on the planet. They are typically employed or funded by foreign intelligence service, national defense organizations, organized crime, or terrorist organizations or they might work alone given a task and funds from any of the organizations listed above. These individuals have the capability of reverse engineering hardware and software. Additionally, they have the capability of writing a very specific exploit code, ability to encrypt various aspects of the code, and fluency in denying attribution through covert channels and darknets to hide their location (Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2 Cyber actor identification.

Attack Sophistication Model

The attack sophistication model is a way to determine the capabilities of an expert level adversary. This is important as the attack sophistication footprint of an expert is far different from that of a novice intermediate cyber actor. We can categorize such models into two different tiers.

Tier 2 (Nonkinectic)

A great example of this type of sophistication was modeled in what the security industry calls “Operation Aurora.” The attack telemetry of this attack was seen in many of the high-tech companies of Silicon Valley. The adversaries who conducted this operation used various known methods to exfiltrate data outside of the network. They were able to compromise a critical vulnerability in Microsoft Internet Explorer that led to their ability to conduct the operation. In addition to the Microsoft Internet Explorer vulnerability, the attackers were able to utilize other methods once they successfully used the browser as their vector to execute their code; they were able to send information about the PC that they targeted that included OS, patch information, and so on, to a command and control server to provide the attacker with clear insight into other vulnerabilities that they can use to harvest whatever data set they wanted to retrieve. Tier 2 attacks are often multistaged attacks that involve multiple vectors as researchers discovered in Aurora.

Tier 1 (Nonkinetic or Kinetic)

These types of attacks are probably the most sophisticated attacks ever written. Finding an example of these types of attacks is difficult because they are not typically shared within the general security community and are executed under the veil of secrecy. These attacks are typically targeted at air-gapped networks or networks that would be considered highly secured, such as those of power companies (supervisory control and data acquisition or SCADA networks), governments, and defense organizations. Additionally, this requires deep insight into a specific vendor’s code base and product offering. These attacks can involve kinetic-based attacks. In 2007, the Idaho National Laboratory conducted a project oddly enough called “Aurora Test.” In this project, it created about 21 lines of code that were injected into a closed test SCADA network and caused a generator to blow up. The ability to weaponize code and use it to conduct kinetic activities is no longer science fiction and unfortunately, it is a sad reality in terms of the threat landscape maturity. However, in the Aurora Test example, it does require someone with inside knowledge and possible source code to successfully execute. What is even more alarming about the weaponization of malicious code is that it could end up in the hands of a terrorist organization. A timely example of a Tier 1 attack is Stuxnet. At the time of writing this book, there is no known patch to fix this very sophisticated attack. The attack was so targeted that it went after a piece of SCADA gear that is developed by Siemens, the maker of SCADA gear. Stuxnet was targeted at two of Siemens Program Logic Controllers (PLC), reported to be the same models as those used by Iran, which delayed Iran from bringing on their nuclear reactors online. Additionally, there was a lot of intelligence wrapped in the code, it was smart enough to discern what devices to arm its destructive payload and also had the ability to terminate after a predefined date. What is important to note is that Tier 1 attacks do require a “pawn” to deliver the malware as in the case of Stuxnet; these types of infrastructures are air-gapped.

It is important to realize that Tier 2 and Tier 1 attacks can be categorized under the umbrella of Advance Persistent Threats. The level of severity and sophistication requires a subcategory to understand what the compromised target is dealing with. Although Advanced Persistent Threats are not new, the fact is that they have received huge media attention in 2010 with Operation Aurora and Stuxnet; the broader security community is only beginning to get a taste of the maturity and sophistication used by cyber actors that will only continue to challenge both the security professional and security vendors. Lastly, the great thing about Operation Aurora and Stuxnet is that “we” the security know about them. What is frightening is that those classes of attacks that we mentioned above are those that are sitting dormant on a system and waiting for a specific instruction set to become active. Stuxnet, is just one example that was targeted at Siemens gear; what about other vendors? Additionally, with the rapid outsourcing of engineering and supply chain manufacturing to foreign nations that have very loose controls on those they hire, it might come as no surprise that we might be enabling the delivery of advanced/invisible code in a vendor’s product life cycle development process or supply chain insertion. The authors are not advocating that outsourcing is a bad thing; it makes perfect economic sense in highly competitive markets that require quick time-to-market and the ability to staff a project with a lot of full-time engineers (FTEs) at a fraction of the cost they would pay in their home country. What the authors are shining the light on is “do you know the backgrounds of the individuals you are outsourcing source code to, or the contractors that deploy critical infrastructure.” This is just illustrating that the inside threat is real and we need to wake up to the realities of advanced tactics used by adversary countries, crime syndicates, and terrorist organizations in terms of conducting nefarious cyber activities. As we mentioned earlier in the book when discussing social engineering and other tactics to gather information, Tier 1 players are experts in deception and nefarious cyber tradecraft. Just ask yourself a simple question about Stuxnet: how did someone get malicious code on a closed “air-gapped” network? There is plenty of speculation on the “how” it was delivered. The majority of the consensus that we have uncovered was by USB. However, if it was supply chain-driven by a code that was written internally or inserted during manufacturing, then this raises the speculation that this was indeed state-sponsored.

Modus Operandi

The great thing about cybercrime, state-sponsored, and nonstate-sponsored activity is that they sometimes use the same modus operandi in terms of malware, and command and control nodes on the Internet. Although, these command and control nodes can go online very quickly and, just as quickly as they went up, they can be brought down. However, companies such as Damballa, which is leading the industry in botnet detection and remediation, have found similarities in criminal activity from various nefarious cyber actors. On the basis of the type of malware, and command and control infrastructures, they are able to assign group names that help them in identifying similarities in activities that are carried out by nefarious cyber actors. In terms of the attack sophistication model, this would apply to Tier 2 and some Tier 1 attacks. Tier 1 often involves malware that might not call back or beacon to the Internet as these attacks are typically on air-gapped networks. In specific cases such as Stuxnet, researchers were able to find clues left by the author of the code. For example, researchers found the following numeric string in the code: 19790509, which by the way is ISO 8601 for capturing dates. According to Wired magazine “Researchers suggest this refers to a date—May 9, 1979—that marks the day Habib Elghanian, a Persian Jew, was executed in Tehran and prompted a mass exodus of Jews from that Islamic country.” There were additional messages found in the code that would indicate that it came from Israel or the United States because of their support of Israel. Additionally, extremist groups such as terrorists are keen on dates and conducting operations that coincide with those dates. Our thoughts on the matter might differ; deception is key and someone could have easily placed those markers in the code to misdirect the analysis to start looking for attribution vectors for the author of the code. That date is also the anniversary of the second Unabomber attack. Does this mean that the code was created at Northwestern University? At the time of writing this book, we have not come across anything that links attribution or modus operandi to a state-sponsored actor. However, the sophistication of this specific piece of malware and its possible destructive properties indicate that it is highly suspected that a criminal organization did not create it as such an organization will be typically focused on preserving data for the purpose of selling rather than destroying them. Modus operandi is just an additional step on our way to attribution.

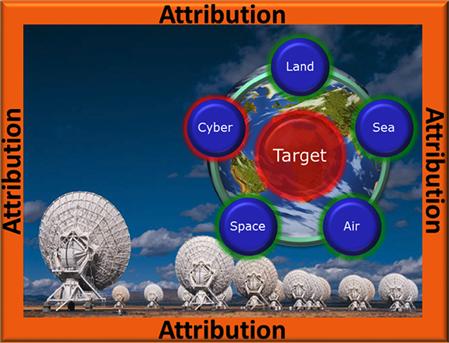

The Importance of Attribution

Every advanced attack that is highly publicized today seems to point back to China as the figure of origin. As security professionals, we would love to believe that attribution was so simple. We have come across situations where the geolocation of an IP address was mapped back to a specific province in China. In some cases, that is very true; the attack did come from China and it turns out that the source was a small school that was infected with malware and used as a pawn to launch the initial attack. Imagine the situation if a defense agency wanted to respond with kinetic means on the basis of the cyber attack and finds out that it just launched an attack on unwitting individuals. That is why attribution is so important and to just lay the blame on China is becoming more of an annoyance. The following image is just an example of how easily you can trace an IP address. If we were to use a Tor client or anonymous proxy and run the same lookup, we would receive an entirely different result. Additionally, even if attribution can be traced back to a source country, it does not necessarily mean that it is state-sponsored. It could be a few bored college students having fun. That is why it is important to look at the attack sophistication model, modus operandi, and origin of the attack. The following is an example of tracing attribution based on IP address. This so happens to be the geolocation of one of the authors. The city and postal code are incorrect; however, if someone with authority contacted the ISP with IP address and host name, he or she would easily be able to trace this back to one of the authors.

http://www.maxmind.com/app/ip-location

Your main IP address: X.X.X.69 United States

Location (from MaxMind database) city: Cedar Park

Local IP addresses detected: 10.0.1.5

Browser variables that may reveal your system, time zone and language Date: Sun Oct 03 2010 10:35:48 GMT-0500 (CDT)

User agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; U; Intel Mac OS X 10_6_4; en-us) AppleWebKit/533.18.1 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/5.0.2 Safari/533.18.5

Standard HTTP request variables that may reveal your system, language, or indicate proxy usage:

HTTP_ACCEPT_ENCODING: gzip, deflate

HTTP_USER_AGENT: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; U; Intel Mac OS X 10_6_4; en-us) AppleWebKit/533.18.1 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/5.0.2 Safari/533.18.5

The authors ran another test using a proxy anonymizer and were traced back to the United Kingdom. That is why attribution is so important in terms of uncovering the real IP address, and geolocation of someone is not that easy and requires, in some cases, working with national and international Internet services providers.

Your main IP address: X.X.X.130 United Kingdom

Local IP addresses detected: 10.0.1.5

Browser variables that may reveal your system, time zone, and language date: Sun Oct 03 2010 10:50:48 GMT-0500 (CDT)

User agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; U; Intel Mac OS X 10_6_4; en-us) AppleWebKit/533.18.1 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/5.0.2 Safari/533.18.5

Standard HTTP request variables that may reveal your system, language, or indicate proxy usage:

HTTP_ACCEPT_ENCODING: gzip, deflate

HTTP_USER_AGENT: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; U; Intel Mac OS X 10_6_4; en-us) AppleWebKit/533.18.1 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/5.0.2 Safari/533.18.5

Additionally, if you wanted to hide your tracks on the Internet, it is not that hard. A nefarious cyber actor can launch an attack from China through a lot of different anonymous connectors (Onion Routed Networks, proxies, or Darknets), but the attack can look like it is coming from Austin, Texas, or Chicago, Illinois (Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3 Attribution.

Now we have touched on the finer points of the classification, attack sophistication, modus operandi, and attribution characteristics associated with categorizing the entities responsible for the cyber activity we read about in the media.

Criminal and Organized Syndicates

Cybercrime is one that has become so profitable for criminals that it has surpassed the drug trafficking trade according to recent reports from the Federal Bureau of Investigation. It is much easier for a criminal to conduct nefarious activities online than actually physically breaking into a bank or someone’s home. In a recent article that was posted on net-security.org, great details are provided on the dynamics of cyber mafia activities on the Internet. The following are the roles that are played out in these types of organizations:

1. “The coder, the ‘techie’ (that keep the servers and ISPs online)

2. The hacker (actively searches for vulnerabilities to exploit)

3. The money mule, the fraudster (creates social engineering schemes), and others.”1

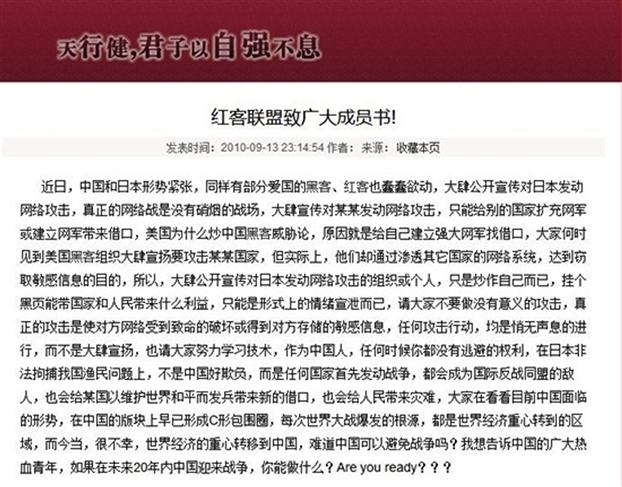

The money mule is an important aspect of the entire operation. The money mule is the one in charge of actually setting up multiple bank accounts with multiple false identities. A great example of this is the recent Zeus Trojan that was targeted at the banking industry. In this specific case, IIya Karasev of Russia entered the United States on a J-1 visa and then later converted his status to an F-1 student visa. Under these specific visas, a foreigner has the right to open a bank account in the United States. However, IIya opened up three accounts, under three different passports all at the same bank but at different branch offices. In order to fly under the radar, IIya never exceeded the amount of 10,000 USD in wire transfers or deposits. That is because any cash transaction over 10,000 USD in the United States has to be reported to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). There is a way of avoiding detection by what is called “structuring deposits,” which means that instead of depositing 10,000 USD, you structure the deposit over two instances of 5000 USD.2 Nevertheless, these individuals were able to steal almost 900,000 USD according to various reports. However, that is not the point of mentioning this specific case. What should be alarming to you is that this criminal group possessed multiple passports from different countries and used them effectively within the United States. Such cybercrime groups are very good at their tradecraft and willing to risk a lot for what might be a significant payout in the end. Additionally, this is just an example of a recent case that has ties to Eastern Europe cybercrime rings. However, the majority of what are categorized as crime syndicates are often anonymous. The first organization that comes to mind when talking about cybercrime syndicates is the Russian Business Network (RBN). It has been allegedly tied to the Storm botnet and the authors of MPack. MPack is a pay-for hacking tool that can run from 500 to 1000 USD. The majority of the targets from cybercrime range from identity theft, stolen credit cards, money laundering, exploit frameworks, and selling services that enable other cyber actors to rent/lease botnets and other nefarious services. Russia is not the only alleged country that has cybercrime rings running in their borders. Cybercrime has been traced back to China and a well known hacker organization called Honker Union of China. It is reported that this organization has about ∼80,000 members and is vocal in communicating their activity. For example, it recently published the following on its Website, which has been converted from Chinese to English as shown in Figure 7.4.

Figure 7.4 Original “Notice to Honker Union general members.”

“Notice to Honker Union general members!

Recently, tension has been built up between China and Japan, some of the patriotic hackers and honkers also are ready to make a move, boldly publicizing to launch network attacks on Japan. The real war on the networks has no smoke and fire. Publicizing to launching cyber attacks against certain country can only give excuses for other country to establish network army and network forces. Why does the United States claim Chinese hackers a threat? The reason is to give excuses for themselves to build up a strong network army. When have you ever heard the American hackers organizing publicly to launch cyber attack against certain country? But in fact, they meet the objective of stealing sensitive information by infiltrating other countries’ network systems. Therefore, the organization or the person who boldly publicized to launch network attacks against Japan is only doing a publicity stunt for themselves. What benefit can hacking a web page bring our country and the people? It is only a form of emotional catharsis, please do not launch any pointless attacks, the real attack is to fatally damage their network or gain access to their sensitive information. Any attack will be executed silently, rather than vigorously promoting it. And also everyone please work hard on learning technologies, as Chinese, you have no right to escape the responsibility at any time. On the issue of Japan illegally arrested our fishermen, it is not that China is easy to be bullied, but any country that starts a war will become the enemy of the international anti-war alliance, which will give certain country new excuses to send troops to maintain peace in the world, and also will bring disaster to the people. Please take a look at the situation China is facing today, China on the map is already being surrounded by a c-shaped ring. Every world war always broke out from where the world economy shifted to, and today, unfortunately, the world economy center is shifting to China, can China avoid a war? I want to tell the vast number of passionate young people in China, if China is in war in the next 20 years, what can you do? Are you ready???.”3

This type of messaging goes against your typically organized crime modus operandi, as most crime syndicates would not post a manifesto and call to action. However, it is estimated that the Honker Union of China has 80,000 members that can carry out nefarious activities. It is best known for its attack on the White House Website. Another group in China called Black Hawk was shut down by Chinese authorities from profiting in selling exploit tools and teaching the trade craft associated with hacking. It has been reported that Black Hawk made over 1 million USD during their time of operation with over 12,000 paying members. In the following section, we discuss other tools that are used in cybercrime activity and tools such as a MSR206.

A common tool that is used by cybercriminals is the magnetic stripe reader or writer (MSR206) shown in Figure 7.5. This allows the cybercriminal to populate and read data from credit cards and other mediums that use magnetic stripe readers.

Figure 7.5 MSR 206.

Another tool that is commonly used but requires physical interaction with the target is ATM skimming. This adds a skimmer to an ATM that blends right in with the ATM. At first glance, you might find it somewhat challenging in being able to identify the skimmer. The skimmer mounts directly over the slit where you insert you credit card, as shown in Figure 7.6. Additionally, skimmers often have pinhole cameras that provide the cybercriminal a visual when you enter your PIN on the ATM.

Figure 7.6 ATM Skimmer Device.

As we mentioned, the majority of cybercrimes are conducted in a logical manner with the exception of ATM skimming, which requires you to physically deploy and harvest once the cyber actors have conducted their operation. Cybercrime is a big, lucrative business that is fueled by the almighty dollar, and the ability to cash in on the lowest common denominator in terms of attack vector.

Nation States

Nation States have often been the focus around major Internet attacks that have been targeted at Nation State networks and Web servers. Unlike the cybercriminals trying to turn a buck or make money from their nefarious cyber operations, Nation States have a different agenda. Those operations that are run from Nation States can range anywhere from disinformation to economic, political, and/or military gain. The disconcerting and scary aspect about Nation State cyber activities is that they are well-funded, employ some of the world’s most talented security engineers, and for the most part are under a veil of secrecy. Nation State cyber programs often operate under the direction of the country’s defense organizations, foreign intelligence services, and country level law enforcement. Additionally, some Nation States have been known for funding subnational entities such as terrorist and extremist groups.

Subnational Entities

A great example of a terrorist group that is state-sponsored is Hezbollah, which operates out of Lebanon and received a lot of its military and tactical training from Iran’s Revolutionary Guard. Although Hezbollah is seen as a positive enabler to the social services fabric in the eyes of the Lebanese, it is deemed a terrorist organization by many, and is well-funded by Iran and Syria. The following is a brief example of Hezbollah’s cyber capabilities:

• Hezbollah profile (a.k.a. Hizbollah, Hizbu’llah) established in the 1980s

• Home base: Lebanon, but it also has cells in North/South America, Asia, Europe, and Africa

• Support: Iran and Syria provide substantial organizational, training and financing

• Orientation: Hezbollah is a radical Iranian-backed Lebanese Islamic Shiite group

• Funding: estimated at 60 million USD annually

• Size: Hezbollah’s core consists of several thousand militants and activists

• Equipment: Hezbollah possesses up-to-date information technologies—broadband wireless networks and computers

• Cyber capabilities: global rating in cyber capabilities—tied at number 37

• Hezbollah has been able to engage in fiber optic cable tapping, enabling data interception, and the hijacking of Internet and communication connections.

• Cyber warfare budget: 935,000 USD

• Offensive cyber capabilities: 3.1 (1 = low, 3 = moderate, and 5 = significant)

• Cyber weapons rating: basic—but developing intermediate capabilities4

During a recent conflict between Israel and Hezbollah, the onslaught of cyber attacks from Israel caused Hezbollah to basically cut all fiber communications coming into the country of Lebanon. The cyber tactics used by Israel during this conflict were mainly psychological, and messages from Israel were delivered to almost 700,000 citizens of Lebanon through the nation’s telecommunications infrastructure in the form of voice mail. That is just one example of the sophistication and reach that Israel has in terms of cyber capabilities. Hezbollah responses were somewhat amateur in terms of launching DDoS attacks and Website defacements that depicted racial and antisemantic language. Nevertheless, you can see that a terrorist organization such as Hezbollah has basic cyber capabilities, but with the backing of another Nation State. As we have mentioned, Nation State-sponsored activity is shrouded in secrecy in terms of capabilities and technology they use for conducting Information Operations (IO) against other countries and/or terrorist and extremist groups. The countries that have been vocal about their cyber capabilities are as follows.

China: The Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) has formulated a cyber warfare doctrine that outlines a strategy for it to become the world’s leader in terms of cyber warfare. According to the Asia Times, in 2010 China is expanding research and development into “network-based combat, including cyber-espionage and counter-espionage.” Within the Chinese military is what is known as the “Military Intelligence Department” that contains seven different bureaus. Each bureau within the Military Intelligence Department carries out a very specific task. However, the seventh bureau deals with cyber intelligence operations that provide the capabilities to conduct espionage, surveillance, and other electronic means to gather intelligence. In addition to its link with China’s government cyber program, it is also integrated with the country’s major universities and research-and-development organizations. On the basis of the sheer size and population of China and its aggressive stance in expanding its own cyber operations, it is likely that it will continue to be one of the key players in cyberspace. The following is an example of its capabilities as of May 2008:

China PLA military budget: 62 billion USD

Global rating in cyber capabilities: number 2

Cyber warfare budget: 55 million USD

Offensive cyber capabilities: 4.2 (1 = low, 3 = moderate, and 5 = significant)

Cyber weapons arsenal: in order of threat:

• Large, advanced botnet for DDoS and espionage

• Electromagnetic pulse weapons (nonnuclear)

• Compromised counterfeit computer hardware

• Compromised computer peripheral devices

• Compromised counterfeit computer software

• Zero-day exploitation development framework

• Advanced dynamic exploitation capabilities

• Wireless data communications jammers

• Cyber data collection exploits

• Computer and networks reconnaissance tools

• Embedded Trojan time bombs (suspected)

• Compromised microprocessors and other chips (suspected)

Cyber weapons capabilities rating: advanced

Broadband connections: more than 55 million5

Russia: Russia possesses a mature cyber warfare model and doctrine. This was very evident during the altercation between Russia and Estonia. The capabilities demonstrated during that cyber campaign basically shut down the entire country of Estonia off the Internet grid by denied access to the Internet. The following is a brief synopsis from Kevin Coleman on the cyber capabilities that Russia is known to have as of May 2008:

Russia’s 5th-Dimension Cyber Army military budget: 40 billion USD

Global rating in cyber capabilities: tied at number 4

Cyber warfare budget: 127 million USD

Offensive cyber capabilities: 4.1 (1 = low, 3 = moderate, and 5 = significant)

Cyber weapons arsenal in order of threat:

• Large, advanced botnet for DDoS and espionage

• Electromagnetic pulse weapons (nonnuclear)

• Compromised counterfeit computer software

• Advanced dynamic exploitation capabilities

• Wireless data communications jammers

• Cyber data collection exploits

• Computer and networks reconnaissance tools

• Embedded Trojan time bombs (suspected)

Cyber weapons capabilities rating: advanced

Broadband Connections: 23.8 million+6

The bottom line is that Russia is very advanced in IO and, like the Chinese, has many universities from which to pick and choose engineers. According to an article by Kevin Coleman, Russia graduates over 200,000 people in science and technology every year. That is not to say that all will join the government, but this gives them an extremely large talent pool to select highly qualified individuals from.

Iran: The following is a brief example of the estimated cyber capabilities that Iran possesses.

Iran Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC) military budget: 11.5 billion USD

Global rating in cyber capabilities: top 5

Cyber warfare budget: 76 million USD

Offensive cyber capabilities: 4.0 (1 = low, 3 = moderate, and 5 = significant)

Cyber weapons arsenal (in order of threat):

• Electromagnetic pulse weapons (nonnuclear)

• Compromised counterfeit computer software

• Wireless data communications jammers

• Cyber data collection exploits

• Computer and networks reconnaissance tools

• Embedded Trojan time bombs (suspected)

Cyber weapons capabilities rating: moderate to advanced

Reserves and militia: reserve with an estimated 1200

Broadband connections: less than 100,0007

These are just a few examples of the capabilities that Nation States have in their cyber arsenals. The United States, United Kingdom, France, India, Pakistan, North Korea, and Japan have very mature cyber warfare models and doctrines that provide them with very specific capabilities to carry out various levels of cyber operations.

Summary

In this chapter, we discussed the capabilities of various cyber actors and provided some models that help articulate the characteristics and sophistication levels of various groups. One key element is attribution of the attacker. We gave a few examples of methods to trace back attribution. Attribution on a global level does require a lot more analysis and clarity. In terms of criminal activity across borders, clear attribution requires the help of state and local law enforcement and information from Internet services providers, which can take a long time if the attack is coming from another country. The cyber actors that are involved in cybercrime, cyber warfare, and cyber terrorism are driven by economic, political, and moral agendas. We have seen that the threat landscape has been constantly evolving over the past two decades. These changes have shaped the dynamics of what we are dealing with today, in terms of the threat landscape. The following is just an example of walking down memory lane and a glimpse into what the future will hold if we continue at this pace.

The first decade (1992–1999): The Internet was a nice-to-have luxury. The profile of the attacker was all about control and named individuals taking responsibility for Web defacements, worm propagation, and so on.

The second decade (2000–2009): The Internet is now a utility and required to compete on a global level and staying connected from a personal perspective. This era presented us with many challenges as the expanding e-commerce, banks, electric and utilities, governments, and military remain online 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and 365 days a year, as well as provide the nefarious cyber actors with many targets on which they could attack for financial gain. Additionally, Nation States are regarding the Internet as a national asset and, as we mentioned, are spending upward to a billion dollars in order to defend it.

The third decade (2010–present): As we move into a new decade and threat paradigm, it is likely that we will witness a cyberkinetic attack. Stuxnet was a great example of what could have been a successful cyberkinetic attack. In the event this happens, the attribution factor might be hard to prove, but from what we have learned in terms of terrorist organizations it appears that they are the only ones that will claim publicly that they were responsible for the attack. At least, this gives the analyst and security experts working the case a place to start from. With each new decade and major technology innovation driving us more into a dependant connected society, the attack landscape will only become wider and much harder to defend if we give security a backseat or treat it as a checkbox.

References

1. K. Honker Union of China to launch network attacks against Japan is a rumor. China Hush 2010; Retrieved October 5, 2010, from www.chinahush.com/2010/09/15/honker-union-of-china-to-launch-network-attack-against-japan-is-a-rumor/; 2010.

2. Coleman K. Hezbollah’s cyber warfare program. Defense Tech 2008; Retrieved October 5, 2010, from http://defensetech.org/2008/06/02/hezbollahs-cyber-warfare-program/; 2008.

3. Dumitrescu O. Considerations about the Chinese Intelligence Services (II). Conflict Resolutions and World Security Solutions 2010; Retrieved October 5, 2010, from www.worldsecuritynetwork.com/showArticle3.cfm?article_id=18347&topicID=66; 2010.

4. Fisher D. Inside the Aurora (Google attack) malware. undated Threatpost 2010; Retrieved October 5, 2010, from http://threatpost.com/en_us/blogs/inside-aurora-malware-011910; 2010.

5. Fulghum D. Cyber-attack turns physical. Aviation Week 2010; Retrieved September 28, 2010, from www.aviationweek.com/aw/generic/story_channel.jsp?channel=defense&id=news/asd/2010/09/27/05.xml&headline=Cyber-Attack%20Turns%20Physical; 2010.

6. Krebs B. Would you have spotted the fraud?. Krebs on Security 2010; Retrieved October 5, 2010, from http://krebsonsecurity.com/2010/01/would-you-have-spotted-the-fraud/; 2010.

7. Lam W. Beijing beefs up cyber-warfare capacity. Asia Times Online: 2010; Retrieved October 5, 2010, from www.atimes.com/atimes/China/LB09Ad01.html; 2010.

8. Langner R. Stuxnet logbook. Langner 2010; Retrieved January 5, 2010, from www.langner.com/en/; 2010.

9. Macartney J. Chinese police arrest six as hacker training website is closed down. The Times 2010; Retrieved October 5, 2010, from www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/asia/article7019850.ece; 2010.

10. Staff C. Hezbollah (a.k.a Hizbollah, Hizbu’llah). Council on Foreign Relations 2010; Retrieved October 5, 2010, from www.cfr.org/publication/9155/hezbollah_aka_hizbollah_hizbullah.html; 2010.

11. Vijayan J. Zeus Trojan bust reveals sophisticated “money mules” operation in U.S. Computerworld 2010; Retrieved October 5, 2010, from www.computerworld.com/s/article/9189038/Zeus_Trojan_bust_reveals_sophisticated_money_mules_operation_in_U.S.?taxonomyId=82&pageNumber=2; 2010.

12. Villeneuve N. Vietnam & Aurora nartv.org. www.nartv.org/2010/04/05/vietnam-aurora/; 2010; Retrieved April 5, 2010, from.

13. Zetter K. New clues point to Israel as author of Blockbuster worm, or not. Wired News 2010; Retrieved October 5, 2010, from www.wired.com/threatlevel/2010/10/stuxnet-deconstructed/#ixzz11Eh1Y5vc; 2010.

14. Zorz Z. The rise of Mafia-like cyber crime syndicates. Help Net Security 2010; Retrieved October 5, 2010, from www.net-security.org/secworld.php?id=9060; 2010.

1 The hacker (actively searches for vulnerabilities to exploit)

2 The hacker (actively searches for vulnerabilities to exploit)

3 www.chinahush.com/2010/09/15/honker-union-of-china-to-launch-network-attack-against-japan-is-a-rumor/

4 The whole bulleted list is from http://defensetech.org/2008/06/02/hezbollahs-cyber-warfare-program/

5 The whole list is from http://defensetech.org/2008/05/08/chinas-cyber-forces/

6 The whole list is from http://defensetech.org/2008/05/27/russias-cyber-forces/comment-page-1/

7 The whole list is from http://www.irandefence.net/showthread.php?p=773407