Seven Commonalities of Subversive Multivector Threats

Information in this chapter

• Seven Commonalities of Subversive Multivector Threats

• Five Names in Threats You Should Know

• Next-Generation Techniques and Tools for Avoidance and Obfuscation

Introduction

The advanced persistent threat (APT) is menacing. It is a silent killer, the cancer of the information age. Like cancer, the APT is more often than not difficult to describe and even more challenging to identify as it is rare that any two examples are the same. Often hiding in plain sight, the APTs and those responsible for their introduction are well-versed in intelligence and information gathering techniques, as well as tactics, execution of strategy, philosophy, and obfuscation.

Their conscription and use of tools—whether they are malicious code and content or personal—are both effective and purposeful. Their mission—its definition and execution directly related to their goals (which in the case of the APT are defined and identified prior to operational commitment)—is a resolute and exact one.

Seven Commonalities of Subversive Multivector Threats

As discussed in Chapter 8, it is the opinion of the authors that there are approximately seven elements considered and deemed necessary to the development, strategy, tactics, conscription, and successful mission completion of advanced persistent threats. Although the elements may bear a resemblance to one another, and the order and precedence of their use will depend on many variables, the following short list provides a representative sample that is both concise and cogent. Bearing that in mind, it is equally important to note that a change in circumstances can and often will influence the nature of the mission, and as such the interpretation of the environment as well as availability of the target(s) in question. The seven commonalities of subversive multivector threats (SMTs) are as follows:

Prior to descending into the world of the SMTs, a short discussion regarding the seven commonalities of SMTs, and their importance to the successful execution of compromises is warranted. It is the authors’ belief that many professionals (information security centric or not), having never been exposed to the world of military data intelligence or the intelligence community at large, require some level of introduction and indoctrination. Moving forward without doing so could be perceived as irresponsible.

As the reader will see, there are infinite arrays of characteristics and methods at work, taking place over time in a slow and often calculated manner. This is not by chance, but rather by design. To be able to avoid attracting unnecessary attention of prying eyes is of critical importance as we have seen and discussed in previous chapters. Tactics and measures for doing so are readily available to operators. Whether one is providing easement to a host or system or Nation State, tools and tactics that aid in completing the mission successfully using whatever means necessary—psychological, social, logical, physical, or a combination of all of the above—can be had with relative ease. Understanding the nuances at play today within the threat landscape and world at large is empowering. Being able to marry tools and techniques to accomplish an end (often in the form of a blended threat—one that contains multiple threats of various denominations), although new, represents a greater threat than perhaps ever encountered. The application of organized thought, disciplined application, and execution of techniques increases the likelihood of success exponentially, provided the opponent(s) is not as fluent in counter-offensive measures. As we progress through this chapter, it is the hope of the authors that this will become more evident and that any ambiguity associated with this concept will be removed.

Reconnaissance

Reconnaissance is neither new nor revolutionary in both practical execution and concept. In fact, it is quite old as anthropologists and historians alike would (and do) tell us—often during the context of a broader discussion or dialogue on the topic of humanity, its patterns, and behaviors. As such, one might argue that reconnaissance is and has always been an elementary aspect of human life and our evolution on the planet. We perform reconnaissance on a daily basis in the modern world when we seek out new environments which we visit and perhaps live in. We check the surroundings to see if any opposition—natural or otherwise—might be encountered and make decisions on whether or not to proceed as a result. Similarly, as we see in anthropological studies, human beings have leveraged reconnaissance in a manner that can only be described as integral toward its survival. In hunting, gathering, and in the course of making war, humanity has valued and will always value reconnaissance.

Reconnaissance in modern parlance is the execution of exploratory activities in order to seek and gain information. It enables one party to determine the intention(s) of another party by collecting and gathering salient information about the other party’s composition and capabilities in addition to other pertinent information—environmental conditions such as logistics, position, activities, defensive positions, and so on. In military tradition, this work occurs directly or indirectly, via elite, highly trained scouts and intelligence units trained in critical surveillance and observation. During the Vietnam War, the United States Marine Corps Force Reconnaissance developed two primary mission functions in order to expand on and perfect this function. They first focused on what had less to do with altercation and confrontation of hostile enemies. United States Marines refer to these types of reconnaissance missions as “keyhole” or “green” ops. These missions and the associated tactics and techniques utilized during the course of the operation and mission were created in order to conduct deep reconnaissance tactics.

The mission was clear: identify, gather, and collect all pertinent intelligence of military importance while observing, identifying, and reporting adversaries and salient details pertaining to them. The secondary sets of mission functions developed by these United States Marine Corps Force Reconnaissance units were developed with the intention of actively seeking out and engaging enemy forces. They were and are, considered to be the inverse of “keyhole” or “green ops” missions where operators in the field actively attempt to avoid contact or engagement with enemy forces focusing themselves on more passive, observationally relevant activity rather than combat. These types of reconnaissance missions were referred to as “sting ray” or “black ops” and required, as previously stated, direct action (DA) as opposed to passivity.

Black operations (often conducted in unison with or on behalf of intelligence community representatives) rely heavily on the inclusion of shock and awe or rapid dominance. These doctrines are on the basis of the use and employment of overwhelming force and power in parallel to dominant battlefield awareness maneuvers in addition to spectacular demonstrations of strength in order to paralyze the adversary’s perception of the battle, the battlefield, and their opponent, culminating in the destruction of the enemy’s willingness to fight.

Electronic intelligence reconnaissance and surveillance is, in many respects, not different from direct in-country deep reconnaissance or DA-based operations. Fields of battle change as do theaters of operation. Adversaries come and go; however, their missions remain clear to both the aggressor and defenders. Bearing this in mind, we should be well-versed in all tactics and strategy—defensive, offensive, conventional, and unconventional—in order to ensure our preparedness to assume either role depending on need and circumstances. Whether state sponsored, subnational, independent, criminal, or otherwise, there are many who are fully qualified in reconnaissance and surveillance operations in the traditional sense and that associated with the cyber realm.

Infiltration

Traditionally, the art of infiltration is associated with gaining an access or entry into a physical location, an organization, a nation, or some other target of opportunity—previously defined and designated or done so as necessity dictates. Infiltration is synonymous with entry without authorization. Regardless of which definition or word suits your needs more appropriately, the implied meaning is the same, as is the generalized reaction to being infiltrated—no one likes it and most are opposed to it and demonstrate attitudes reflecting their opposition (at times with hostility) to being infiltrated without apology.

As with reconnaissance operations (green or black), successful infiltration is often dependent on previously known intelligence applied in real time or near real time depending on the circumstances and objectives requiring attainment, in addition to the ability to remain hidden in plain sight. Depending on the situation at hand, it may require great risks to be taken while at other times, it may seem much less exciting than what one may encounter in a Hollywood feature film. Nonetheless, infiltration is an integral element in all compromises especially in those related to or servicing the advancement and promotion of advanced persistent threats. Often, infiltration requires duplicity or subterfuge. Subterfuge, it can be argued, is an integral element in the success or failure of operations of this sort. Regardless of the form factor that the infiltration takes, deception—even for the greater good—does not come naturally to most human beings, which is not a bad thing as it suggests that because it is uncomfortable for most to lie (even when necessary), we do not have a society of sociopaths running around causing chaos. At times, the ability to convincingly engage in subterfuge requires a great deal of cultivation, refinement, and guidance to ensure effective delivery. Similarly, in detecting subterfuge, its use, and presence—especially when investigating the world of the SMTs—or any next-generation malicious code or content incident, this ability becomes invaluable.

The goal of these operatives is clear:

1. Remain hidden in plain sight.

2. Obfuscate one’s true intentions—electronically, verbally, physically, and so on by compromising one or many targets in order to gain the enemy’s trust and in doing so, ensure that the mission remains on time and targeted. Actively engage in and promote subterfuge and deception in order to enhance and promote the goals of your mission as an operator.

3. Avoid any unnecessary attention or risks—in doing so avoid creating an anomaly as a result of one’s attempts to remain discrete. Apply discretion in both thought and deed—think before you act and when necessary.

An operative’s ability to successfully infiltrate a target environment is reliant on the quality of information and intelligence produced via reconnaissance efforts in addition to the operators’ ability to apply their skills, tools, and tradecraft to the intelligence in sound practice. Should these data be faulty or found lacking, the potential for infiltration diminishes greatly and, as a result, so does the potential for a successful operation. Depending on the investment in time, energy, personnel, and tools development, it could call for a redesign or cancellation of the effort. For those tasked with mitigating the risks presented by entities allegedly utilizing technologies and tactics such as APTs, this would be optimal, and in many cases, the best possible situation to find themselves and their environments in. However, we know by virtue of the nature of these threats, their deployment is typically low and slow over time and their success rates—despite the best efforts being made today—are high to say the very least.1,2,3,4

Identification

Identification is the process of establishing the state of a person, place, or thing at a given time. It also describes salient details pertaining to the condition of said person(s), place(s), or thing(s) and, as a result, is crucial to the entire process of information acquisition and gathering. In the world of the SMTs, identification becomes a much more complicated proposition. Not all APTs, as we have discussed earlier, or their missions are created equal. Some stress much more targeted effort and focus with respect to what they are looking for while others are less discriminate. However, where they are all equal is in the area of accuracy. To accurately identify the target and target elements is essential when discussing APT functionality. There is little, if any, room for compromise here and given the nature of the efforts seen over time to date, it is the opinion of the authors that the responsibility of identification is ubiquitous to all participants and operatives partaking in a given operation. Accuracy is nonnegotiable, and as we shall discuss later, the introduction of new technologies to ensure accuracy and integrity is remarkable. As such, it can be argued that regardless of the role of the team member—operational agents or support personnel; field grade operatives or analysts in the garrison—accuracy in identifying people, environmental details, logistical information, and targets is of paramount importance.

The process itself is dependent on many things, many of which reflect items such as the following:

Acquisition

Acquisition refers to the act of obtaining something. Self-explanatory, right? It is the conclusion of the act of acquiring, which is at the heart and soul of attacks that leverage SMTs. What is to be acquired is up to the parties responsible for and behind the attacks. Generally as we have already seen, the “something” to be acquired could be any of the following:

In order to ensure a successful acquisition, the teams in question must have solid information gained through reconnaissance, infiltration, and the identification of targets via analysis of the information gathered via reconnaissance and infiltration leading to acquisition. As such, there is a cyclical element at play here, one that ebbs and flows in relation to change presented by the environment and state of the target(s) in question (Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1 Reconnaissance cycle.

Security

Security is the condition one finds oneself in, which yields a sense of being without care. If you study the etymology of the word itself, security is derived from the Latin word “Se-Cura”—to be without care. SMTs rely on stealth, precision, and attention to detail in order to preserve the state of security the cyber actors enjoy while engaging in their missions. As we continue to define and study the role that reconnaissance plays in the execution of threats of this type, we must ensure that we pay attention to detail by not taking any for granted. The devil is in the details, and with respect to sophisticated cyber threats one can never be too careful or assume that the improbable is impossible. Rational decisions are made on the basis of the analysis of facts and information and intelligence gathered through reconnaissance efforts and infiltration.

In our industry, we associate the term with a given form or state or posture often achieved via the institution and application of people, process, and technologies.

With respect to SMTs, the architects behind these threats are fully cognizant of how and why the industry approaches security and, perhaps more importantly, what the industry and practitioners consider secure. In studying their targets, they have enabled themselves to bypass and evade commonly held practices and technologies. As we shall see shortly, were this not the case, there would be far fewer examples of APTs exploiting for years on end critical infrastructure and systems within the United States and beyond.

Extraction

Getting out unscathed and uncompromised is as important in APT-based attacks as it is in traditional physical scenarios. The extraction is as important as the insertion—no one wants to get hurt and everyone wants to go home. In cyber security scenarios where the goal of an SMT is to ensure implementation, entrenchment, identification and collection of information and intelligence, and its exfiltration all done in a secure manner, one would be hard-pressed to argue against the importance of the extraction. One’s ability to extract without notice or giving oneself away is of paramount importance.

The ability to employ stealth is of vital importance. During extraction—whether it is the initial extraction or successive extraction—stealth, the ability to remain covert, cannot be overemphasized. This stealthy quality, when coupled with other aspects of SMTs, increases the difficulty (as we have already discussed), exponentially. This is exactly why the authors and architects behind and responsible for attacks driven by APTs are (and have continued to be), tirelessly working on employing advanced methods of obfuscation and suppression to their solutions.

Delivery

Ultimately, the end game with all SMTs is the unfettered, successful delivery of the target information or intelligence to those responsible for the attacks or their clientele. Delivery in the realm of the SMT has advanced in both concept and execution just as we have seen in other areas. It continues to do so, whether or not we wish to recognize it or not. The manners in which these advances occur are as varied as the types of SMTs and uses identified.

Examples of Compromise

Over the last 12 years, examples of compromise tying back to APTs have become more and more frequent. Responses to the apparition of the “APT” have varied from dismissive, to disbelief, to questionably informed paranoia, to the less common but most appropriate, educated and coherent understanding of the problem at hand. The information security industry, the media, enterprises, and individuals all fall within this spectrum. In many cases, there was no acknowledgment, or perhaps more accurately, little acknowledgment if any at all, until well after their identification, verification, and the conclusion of the investigation. The United States Intelligence community and Department of Defense (DoD) communities are still actively investigating at least one case, Moonlight Maze. In this case, as we shall learn in the following section, there is little to no speculation with respect to its reality and existence. (We discuss and describe this case and others like it in the following section.) It is important to note that in most cases, information pertaining to the presence or existence of an APT (regardless of its status in terms of verification and investigation) is kept confidential and private by the parties having been affected and those performing the investigation.

Many reasons for doing so (whether due to ethics, morality, or legality) can be cited, all of which must be examined against state, federal, and international law. As such, care must be given and maintained throughout these processes and maintained at all times.

Five Names in Threats You Should Know

Solar Sunrise

In 1998, the United States DoD took a bold step forward into the cyber frontier by establishing the first of its units with a dedicated mission to combat cyber threats. This unit, initially known as the Joint Task Force-Computer Network Defense, and its primary reason for existence were to demonstrate that the need for a new approach and attitude toward emerging threat vectors, in particular those associated with cyberspace, was required by the DoD and its affiliates.5 The attitude adjustment came in the form of two key operations:

• Exercise Eligible Receiver 97

• An unnamed cyber attack originally thought to be the work of Iraqi agents in 1998

These exercises served to demonstrate that in addition to being able to inflict a great degree of damage against DoD computer systems and networks, it was also possible to capitalize on non-DoD systems in order to exploit vulnerabilities and thus render nations vulnerable to, and in some cases, potentially helpless against, advanced cyber attacks. Eligible Receiver 97 was directed and overseen by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and run from June 9 through June 13, 1997.6 It was the first-of-a-kind large scale, zero warning, military field exercise designed to test the United States’ ability to respond to an attack on both U.S. civilian and military infrastructure. The operational exercises focused emphasis on key elements of civilian infrastructure such as the following:

• Critical infrastructure (namely power) organizations

• Defense Information System targets within the Pentagon, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Defense Intelligence Agency, Central Intelligence Agency, and other ancillary agencies and commands

Vulnerabilities exploited included but were not limited to the following:

• Operating system vulnerabilities

• System configuration anomalies

• Weak user awareness and operational security cognizance

Additionally, the National Security Agency (NSA) commanded a “Red Team,” which possessed no sensitive internal information, yet was able to successfully inflict a great deal of simulated damage because of the time it took to properly execute reconnaissance of targets of interest.7

The lessons learned as a result of Exercise Eligible Receiver 97 were profound. It was proven to the Joint Chiefs of Staff and other high-ranking officials in the United States DoD and Intelligence Community that significant flaws and vulnerabilities existed not only in the systems that powered them but also in personnel.8 Although the evidence was there to warrant change, the change would come too late as in 1998 the United States would face for the first of what can arguably be considered a series of high-profile cyber attacks known as Solar Sunrise. Solar Sunrise presented an all too real threat and adversary to the people and government of the United States of America. It verified the vulnerability demonstrated in Exercise Eligible Receiver 97, yet unlike that operation which was a military and intelligence community field grade operational event this was an actual event of interest. An unplanned, unapproved event was taking place via a still relatively new communications medium which was now steadily becoming available to allies and adversaries alike the world over. Prior to this event, the concept of large-scale compromise, infiltration, and extraction of data from systems and networks belonging to the United States of America was largely academic, although probable enough to warrant exploratory exercises such as those conducted in Exercise Eligible Receiver 97. The potential for hostile adversarial groups and Nation States to purposefully disrupt or influence the state of the United States of America through the manipulation of information systems and networks was not only attractive but also possible. It was seen as an equalizing factor leveling the playing field for all globally.

In February 1998, a series of attacks were detected beginning on the 1st of the month and continuing on through the 26th of the month. During this period, approximately 11 attacks were launched on various targets belonging to the United States Navy, United States Marine Corps, and United States Air Force, respectively.9 The attacks were predominantly directed toward machines running the Sun Microsystems Operating System Solaris and were classified as denial of service (DoS). The attacks all followed the same attack pattern and profile:

1. Network address space enumeration to determine the presence of a vulnerability

2. Exploitation of the vulnerability

3. Deployment of a malicious program (in the case of Solar Sunrise a sniffing program) to gather data

4. Return to the compromised hosts to gather collected data followed by exit

Given that the attacks were taking place in close proximity to the United States’ intended timeframe for possible combat missions in Iraq, an interagency investigation involving the United States Air Force, United States Navy, United States Marine Corps, United States Army, National Aeronautic and Space Agency, National Security Agency, Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigations, and the Central Intelligence Agency ensued with several court orders being issued in an expeditious manner. Eventually, the investigations led to two California teenagers and an 18-year-old Israeli boy.10 Although none of the systems exploited was classified, it was argued by investigators and prosecutors that the disruptions could have been used to immobilize DoD communications systems, rendering the nation and its fighting forces at a definitive disadvantage should they be called into combat in the middle east.11 As a result of the DoS attacks associated with Solar Sunrise, the DoD chose to move quickly to improve areas of weakness noted in the investigation. The DoD strove to improve operational security by the following measures:

• Increasing situational awareness via the implementation of a 24-hour watch center

• Implementation of intrusion detection systems on critical nodes and segments

• Mature computer emergency response teams (CERT)

• Greater degrees of communication with the FBI’s National Infrastructure Protection Center and other law enforcement agencies (LEA)

The United States DoD continued to face cyber driven computer infiltration challenges beyond the scope of routine computer viruses and relatively unsophisticated hacker attacks. As we shall see in the next section, although precautions were taken to reduce the attack surface noted by various organizations within the United States government (DoD, State Department, NASA, Pentagon, etc.), compromise, exploitation, and extraction of data continued at an alarming rate.

Moonlight Maze

Moonlight Maze is the code name given to a highly classified incident believed by many experts in both information security and intelligence to be the longest lasting example of an advanced persistent cyber attack in history to date.12 Researchers and security experts alike first became aware of the incident in the spring (March) of 1998.13 Officials of the United State government noticed anomalous activity occurring in restricted network environments. Systems within the Pentagon, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the Department of Energy (DOE), Weapons Laboratories, and universities throughout the United States were affected by precise targeted efforts occurring over elongated periods of time. This was markedly different than what had been noted in previous attacks of a similar nature such as Solar Sunrise that preceded Moonlight Maze.14,15,16 Once it had been detected, it was evident to those conducting incident response and analysis (IR) that the threat was focusing on predominantly sensitive yet unclassified information and systems hosting such data. Incident response teams noted on conducting lengthy analysis of the data and affected systems, that the attack had been on going for nearly two years! This was noteworthy, given the nature of the systems and the organizations in which they were located. According to the news media organization FRONTLINE, sources indicated that the alleged invaders had been making their way through thousands upon thousands of files including a variety of data such as the following:

Theories arose in abundance regarding the attribution and origins of the attacks although nothing of a substantial nature was presented. Michael Vatis, the director of the FBI National Infrastructure Protection Center said that the intrusions appeared to have originated in Russia17 although the evidence was deemed circumstantial at best. The consensus seemed clear however that the attacks were of a structured type and most likely originated outside Moscow. What troubled representatives of the collective environments most about the attack was the “magnitude of the extraction.”18 The impact of Moonlight Maze on the day-to-day operations and comfort levels of the environments affected, in addition to the sentiment in Washington, was obvious and profound. Republican Senator Jon Kyl of Arizona chairing a Senate subcommittee hearing investigating Moonlight Maze noted that it was an event of extraordinary significance but certainly not a solitary example. The recognition that Moonlight Maze was but one of many events in 1997 that the people of the United States and its government should be concerned with was quite poignant. As a result of the discovery and investigation of the attack, the Pentagon had ordered $200 million dollars in new cryptographic equipment in addition to having upgraded its intrusion detection solutions and firewalls. These measures were taken to strengthen the risk posture of NIPRNET although their effectiveness would come under scrutiny at later dates as we shall see later in this chapter. Moonlight Maze accentuated serious vulnerabilities found within systems and networks belonging to the United States of America. Many of these systems played key roles in portions of network infrastructure deemed critical by authoritative bodies within the DoD, DOE, and Department of Justice (DoJ) among other federal agencies and departments. Utilizing attack profiles similar to those described in the Solar Sunrise case, attackers were able to carry out the following tasks:

• Enumerate the network address space

• If successful in identifying them, exploit them delivering a malicious payload—in this case a backdoor program enabling the attackers to reenter the system at their leisure in order to identify them

• Conduct other probing activities (some resulting in the destruction of file and system structures)

To date, Moonlight Maze is still being actively investigated by United States Intelligence Agencies.

Titan Rain

No discussion of state sponsored cyber attacks would be complete without discussing the story of Titan Rain and Shawn Carpenter. Neither of these is a household term although in information security and intelligence communities you would be hard-pressed to find someone who had not heard of one or both. Shawn Carpenter is a citizen of the United States of America, a United States Navy (USN) veteran, whistleblower (Mr. Carpenter was previously employed by Sandia National Laboratories when his adventure began), and a hero. Shawn Carpenter was instrumental in tracking down the points of origin for the attacks commonly referred to as Titan Rain today. In 2003, Shawn Carpenter was an employee of Sandia National Laboratories where he worked as a network analyst focusing on security breaches within the Sandia network infrastructure. Like most analysts whose work sees them engulfed by packet captures, trace analysis, and behavioral patterns, Mr. Carpenter performed his work in a vigilant manner on behalf his employer and his country. Sandia National Laboratories had a mission of critical importance to the United States of America. Much of the Nation’s (the United States’) nuclear arsenal was designed there, along with a great deal of advanced energy and military research and development. The work conducted there was of paramount importance and required a dedicated mission-oriented staff to ensure that it remained free from obstruction and threat. In late 2003, Mr. Carpenter had been asked to undertake another mission which was perhaps his most important to date.19 It would see him cross the globe via the information highway taking him to faraway locations in order to establish attribution of foreign entities who had taken it on themselves to explore, compromise, exploit, and extract data from networks like and including those of Sandia National Laboratories.

The mission Mr. Carpenter would assume would see his nights and weekends disrupted for months on end as he tirelessly pored over data armed with coffee and Nicorrette gum.20 His work would see him track a group of alleged Chinese cyber spies bent on gaining deeper access inside American networks while remaining unfettered. He monitored their communications, hidden in the darkness of chat rooms, forums, and covert communications channels recording as much data for future analysis as possible on behalf of his other employers, the United States Army and later the FBI. Mr. Carpenter first became aware of this group of alleged Chinese cyber spies while aiding in the investigation of a breach incurred by defense industrial base (DIB) firm, Lockheed Martin in September 2003. Several months later, Mr. Carpenter would note that an attack with a familiar signature was seen on the Sandia National Laboratories network. After looking into the event more deeply, Mr. Carpenter compared his findings with the findings of a trusted colleague in the United States Army. Both sets of data concluded which a very sophisticated, methodical initiative was underway which was targeting sensitive data contained within network environments deemed sensitive and restricted by the United States Government. These networks housed intelligence related to research and development initiatives, military bases and institutions, DIB contracting firms such as Lockheed Martin, and various aerospace corporations. The attacks were worthy of note and on later investigation were referred to as elegant in their execution. The attackers were well-versed in system architecture and careful in their actions. They sought out hidden portions of hard drives and attempted to aggregate as much data as possible in compressed file structures in order to transmit them in an expeditious manner to drop zones located in South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan prior to forwarding the data on to mainland China.21,22 Their execution was flawless; perfect in all ways. Their escapes were always nonevents; quiet without drawing attention to themselves or their points of egress. They were meticulous in cleaning up after themselves, taking care to remove any telltale signs or fingerprints left behind on the systems that they had compromised. They were sly, leaving behind on all systems enumerated and added to their Web of compromised hosts virtually undetectable beacons that allowed them to reenter a given host without fanfare at will. Their attacks were clean and swift averaging approximately 10–30 minutes per attack. Mr. Carpenter noted that they never made a mistake and took every measure possible to fend off prying eyes. To a security analyst like Shawn Carpenter, the temptation to give chase to these unknown and unwelcome “visitors” to his network and the networks of the United States of America proved quite strong and so he began tracking them globally. His efforts eventually led him to tracking the group to their geographic point of origin in the southern province of Guangdong.23

In Washington D.C, officials remained noticeably quiet with respect to Titan Rain for several years stating only that details related to the case were considered classified. Time magazine was able to confirm that at least three high-ranking officials in government positions considered the breaches outlined in the work conducted by Shawn Carpenter to be serious.24 A great degree of speculation ensued on the disclosure of the breaches and compromises identified by Mr. Carpenter. The FBI began formal inquisition and investigation into the possibility that the attacks were in fact state sponsored by the government of the People’s Republic of China although many still remain noncommittal with respect to the attribution of the attacks. Many researchers and members of both law enforcement and the intelligence community have debated and continue to debate the involvement of the People’s Republic of China in these activities citing the voluminous numbers of insecure workstations and servers that are used on a continuous basis by cyber actors of various denomination to accomplish their agendas.25,26 China’s State Council Information Office has gone on record as saying that the allegations are irresponsible and unfounded.27 Despite the official U.S. silence, several government analysts who protect the networks at military, nuclear-lab, and defense-contractor facilities still maintain that Mr. Carpenter was correct and that Titan Rain is among the most pervasive cyber espionage threats that U.S. computer networks have ever faced. We now know that this unit has grown and rivals a United States Army Brigade in standing troop strength. Examples of the types of information that was compromised and extracted includes the following:28

2. Hundreds of detailed schematic drawings related to propulsion systems, solar paneling, and fuel tanks for the MARS Reconnaissance Orbiter

3. Falconview 3.2 flight planning software used by the United States Army and United States Air Force

The People’s Liberation Army of the People’s Republic of China announced the formal creation of “information warfare units” at the 10th National People’s Congress in 2003. General Dai Qingmin29,30,31 said that Internet attacks would run in advance of any military operations executed by the People’s Liberation Army in order to cripple their enemies while creating fear and confusion. Additionally, he and other Chinese Generals conveyed to that audience and others subsequently that there were six core elements necessary to invoke information warfare successfully:

In 2007, activity associated with the People’s Liberation Army’s cyber-warfare units was noted in Germany and the United Kingdom. Both examples were considered logical extensions of what originated as Titan Rain.32

Compromise of the United States Power Grid and Critical Infrastructure

In March of 2005, Patrick H. Wood33 III had much on his mind. Wood, who is the former Chairman (then the Chairman) of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), had warned the top executives within the electricity industry in a private meeting held in January (only three months prior) that much more emphasis and care needed to be placed on cyber security within their areas of responsibility. In March of 2005, Wood experienced what many would consider a terrifying event.34 He was invited to the DOE’s Idaho National Laboratory for a private demonstration. It was a demonstration that would support the assertions he conveyed to utility corporation executives just three months earlier. So compelling was the demonstration which Wood witnessed that after the fact, he increased his efforts and those of his office in increasing awareness and education about cyber security. The demonstration was a simulation of what could occur if a skilled attacker were to compromise the national power grid. Now, what is interesting about this is that it occurred well after both Black Ice and Blue Cascade during the period 2001–2003 in the Pacific Northwest. Via the demonstration, Wood learned the following:

1. The Internet-based business-management systems in use at the time were highly susceptible to attack

2. On compromising them, an attacker could take control of other systems—systems that control the utility operations environment

3. On gaining access and entry, the attackers could, via the escalation of privileges and exploitation of system vulnerabilities, accomplish the following:

a. Attackers could cut off the supply of oil to the turbine powered generators—the same generators that produce electricity

b. Cause destruction of the equipment and potentially the facility as a result

Ken Watts,35 an employee of Idaho National Laboratory at the time who witnessed the demonstration confirmed the results and the realities presented by the events of that day. When later asked about the events of that day and the impact they had on him, Watts had only this to say, “I wished I’d had a diaper on.”36 A powerfully concise and descript message, one that should have been paid more heed. One might think that on receiving information of that nature the FERC would have immediately begun taking steps to address these issues. However, it would not end there. In August of 2007, Scott Lunsford,37 a security researcher working with IBM Internet Security Systems successfully compromised a nuclear power station. Initially he was told that it would be impossible to do as the infrastructure, he was assured, was not Internet facing. The plant owners were wrong. By the conclusion of the first day, Lunsford had penetrated the network. Within one week’s time he and his team were controlling the nuclear power plant. Obviously, this was a major problem, which foreshadowed others to come. What Lunsford identified were flaws, which would be noted in a report released by the United States Federal Government in the April of 2009. The report was generated and released by the United States Government after completing a full audit of the national power grid infrastructure.

It was the first time that commercial power and utilities companies gave the United States Government permission to conduct such an audit. The results were shocking and provided a grave look into the state of critical infrastructure within the United States in addition to the use and prevalence of APTs sourced by many entities, for the express purpose of deep compromise of the environment.

The report revealed that the Nation States involved included the following:

1. The People’s Republic of China (People’s Liberation Army)—may be a continuation of effort known as “Titan Rain”

What made the report both chilling and infuriating was that in addition to the presence of foreign entities within critical infrastructure of the United States of America (later confirmed by former CIA staff officers), it was pervasive throughout the United States. It was not localized to one region or Power Company but gross in its scope and penetration across utilities (e.g., electric, natural gas, water, etc.). Furthermore, the report revealed the presence of what authorities at the time referred to as “calling cards,” which were later disclosed as being rootkits and backdoors; classic elements and attributes of APT based attacks. 2009 would quickly become the year of the APT and our next example demonstrates this just as clearly as its predecessors.

Byzantine Foothold (“Ghost Net”)

On March 29, 2009, the details of what would become one of the most, if not the most, talked about example of APT activity in recent history were released via a story in The New York Times. The history of this particular attack is intriguing and its depth and breadth are impressive to say the very least. The target of interest was the Office of the Dalai Lama (the Tibetan government in exile), which was, at the time, located in Dharamsala, India. Suspecting that they were the unwitting victims of espionage, the representatives of the Tibetan Government engaged a group of third-party investigators, the Infowar Monitor (IWM). The team comprised researchers from Secdev Group, and other consultancies and research bodies. The results were quite shocking and revelatory.

Compromised systems were identified in 103 countries the world over including systems in the embassies of India, South Korea, Indonesia, Romania, Cyprus, Malta, Thailand, Portugal, Germany, and Pakistan in addition to the Office of the Prime Minister of Laos. In addition to these national embassies, financial institutions within the region were also compromised leading to approximately 1295 hosts having been compromised and identified. Estimates suggested the progression of the attack saw about a dozen computers being attacked on a weekly basis. The attackers in question did not engage with advanced next generation or designer malware. In fact, they engaged their targets after conducting rigorous reconnaissance and assessment of the target environment and were able to use commonly obtainable tools in order to accomplish their goals. Voluminous amounts of data were accessed and harvested by the assailants. Email traffic had been siphoned out of the target hosts while conversations were eavesdropped on using listening and recording devices via integrated microphones and/or Webcams.

Google China Attacks (“Aurora”)

The importance of this specific SMT, which was categorized as an APT, by McAfee Avert Labs was the first real public use case of a specific attack that would have been typically directed at a public sector entity. This attack was very sophisticated and targeted Silicon Valley’s high-tech firms. The attackers used vulnerability in the IE Web browser that allowed them to send an encrypted payload to the targeted host on visiting a given Website. Once the code was executed, it would then set up a covert SSL connection in order to transmit various types of data out of the network. This attack introduced a new class of attack that the mainstream security community thought was new but had been plaguing the public sector and other high profile industry verticals for decades. Up until Aurora, many security vendors didn’t address APTs nor did they talk about them openly. In the case of Aurora, the attackers used multiple vectors that were very sophisticated and required many point security solutions to work together in order to deny the attack. As APTs evolve into SMTs, the security industry is going to have to change a lot of their detection capabilities to include deep packet inspection and the ability to discover covert channels quicker.

Next-Generation Techniques and Tools for Avoidance and Obfuscation

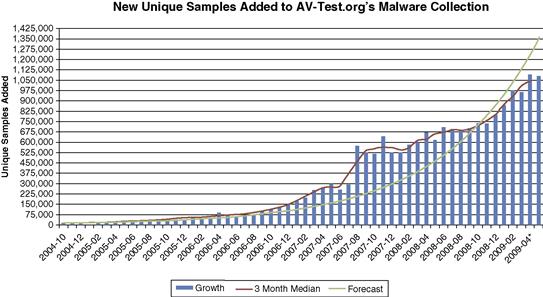

Modern malicious code and content is experiencing rapid-fire change; change occurring at a pace that has not been seen or identified in the past. With respect to these changes, it is important to understand what is occurring with respect to new developments and techniques developed expressly for the detection of signature-based malicious code mitigation solutions, and their avoidance (Figure 9.2).

Figure 9.2 Unique Malware samples as seen by AV-Test.org.

Some information security researchers and analysts believe that as time progresses, this avoidance capability will supersede (and perhaps already has done so to a certain extent) the traditional solutions, thereby forcing the hand of innovation once more. Additionally, obfuscation techniques such as the inclusion of crypto-packs have been noted as becoming more common in our research and research of others. The consensus is that the inclusion of encrypted malware, complete with the ability to decompress and decipher itself, will continue to rise as well, aiding in the ushering in of a new era in both next-generation threats and our ability to detect them.

Summary

In this chapter, we discussed one of the most advanced and sophisticated attack classes called APTs. We decided to pull APTs into what we are calling SMTs with very well-defined elements that allow you to really understand the depth and breadth of the worst attack class known to date. It was also important to illustrate the various use cases as you might recognize that they involved a number of methods dealing with various state sponsored intelligence activities we’ve discussed throughout the book. Additionally, and more importantly, you will also encounter a number of correlations as a number of the methods associated with many other topics we have talked about are being leveraged to carry out cybercriminal activity.

References

1. Graham B. Hackers attack via Chinese Web sites.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved August 31, 2010, from www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/08/24/AR2005082402318.html; 2005.

2. Greenberg A. America’s hackable backbone Forbes.com. Retrieved August 31, 2010, from www.forbes.com/2007/08/22/scada-hackers-infrastructure-tech-security-cx_ag_0822hack.html; 2007.

3. Hensel C. Security. Computing Research Association. Retrieved August 31, 2010, from www.cra.org/govaffairs/blog/archives/cat_security.html; 2010.

4. Johnson B. Nato says cyber warfare poses as great a threat as a missile attack The Guardian. Retrieved August 31, 2010, from www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2008/mar/06/hitechcrime.uksecurity; 2008.

5. Rushkoff D. Google hack attack was ultra sophisticated, new details show Wired.com. Retrieved August 31, 2010, from www.wired.com/threatlevel/2010/01/operation-aurora/; 2010.

1 www.nartv.org/mirror/ghostnet.pdf

2 www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/stuxnet-introduces-first-known-rootkit-scada-devices

3 http://news.yahoo.com/s/afp/20101003/tc_afp/iranitcomputerstuxnet

4 http://blogs.forbes.com/firewall/2010/09/29/did-the-stuxnet-worm-kill-indias-insat-4b-satellite/

5 www.cdi.org/terrorism/cyberdefense-pr.cfm

6 www.globalsecurity.org/military/ops/eligible-receiver.htm

7 www.infosecnews.org/hypermail/9804/0217.html

8 www.fas.org/irp/congress/1999_hr/99-02-23hamre.htm

9 www.globalsecurity.org/military/ops/solar-sunrise.htm

10 www.theregister.co.uk/2001/06/15/solar_sunrise_hacker_analyzer_escapes/

11 www.globalsecurity.org/military/ops/solar-sunrise.htm

12 www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/cyberwar/warnings/

13 www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/newsweek-exclusive-were-in-the-middle-of-a-cyberwar-74343007.html

14 www.globalsecurity.org/military/ops/solar-sunrise.htm

16 www.theregister.co.uk/2001/06/15/solar_sunrise_hacker_analyzer_escapes/

17 http://articles.sfgate.com/1999-10-07/news/17704035_1_russia-based-intelligence-gathering-operation-officials-government-s-unclassified-networks-moonlight-maze

18 “It is the magnitude of the extraction that is alarming to us,” Arthur Money, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Command, Control, Communications, and Intelligence, said in an interview. The hackers, he noted, “can get insight into sensitive operations” even from unclassified files.

19 http://searchsecurity.techtarget.com/news/column/0,294698,sid14_gci1127062,00.html

20 www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1098961,00.html

21 www.breitbart.com/article.php?id=051212224756.jwmkvntb&show_article=1

22 http://csis.org/publication/computer-espionage-titan-rain-and-china

23 www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1098961,00.html

24 www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1098961-2,00.html

25 www.computerworld.com/s/article/105585/Guard_against_Titan_Rain_hackers?taxonomyId=17&pageNumber=1

26 www.heritage.org/research/reports/2007/05/chinas-quest-for-a-superpower-military

27 www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1098961-2,00.html

28 www.futureintelligence.co.uk/content/view/85/63/

29 www.scribd.com/doc/2196587/Cyber-Warefare Cyber-Warfare An Analysis of the Means and Motivations of Selected Nation States

30 www.ists.dartmouth.edu/docs/cyberwarfare.pdf

31 www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/2006/RAND_MG340.pdf

32 www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2008/mar/06/hitechcrime.uksecurity; www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/08/24/AR2005082402318.html

33 www.cra.org/govaffairs/blog/archives/cat_security.html

34 www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn/A25738-2005Mar10?language=printer

35 www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn/A25738-2005Mar10?language=printer

36 www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn/A25738-2005Mar10?language=printer

37 www.forbes.com/2007/08/22/scada-hackers-infrastructure-tech-security-cx_ag_0822hack.html