CHAPTER 9

A Dog’s Tale, by Mark Twain

My father was a St. Bernard dog. My mother was a collie. I’m a Presbyterian. This is what my mother told me. I’m not quite sure what big words like that mean. But my mother liked to say them. She liked to see the looks of surprise and envy on the other dogs’ faces. They wondered how she got so smart. But it was only for show.

Mother liked to listen in on people conversations whenever our people had company. Mother also went to Sunday school with the children, and she learned a lot of big words there. She would repeat words to herself, over and over. She would carry them around in her head like precious jewels. Then, when there was a big dog gathering, she would surprise everyone with a new big word. The dogs who knew her were proud of her vocabulary. The ones who didn’t know her were always surprised by her big words. It made them feel small and embarrassed that they didn’t understand what she said. When they asked her what the big words meant, she always had an answer.

The other dogs were so impressed with Mother’s education, they never doubted what she told them. Perhaps it was because she spoke as though she were reading from the dictionary. Perhaps it was because they had no way of checking whether she was right or wrong. After all, she was the only educated dog they knew.

I believed her, too. That was, until the week when she used the word “unintellectual” at eight different dog gatherings. When asked what it meant, she gave eight different answers. I said nothing, of course. But it did make me doubt how educated Mother really was.

There was one word she always used, like a life preserver. It was kind of an emergency word, for times when conversations took a turn for the terrible or someone dared to doubt her. Mother’s emergency word was “synonymous.” She could always count on this word to catch a new dog off guard and make him speechless. For example, if some curious dog asked Mother what something meant and she didn’t want to tell him exactly, she would instead reply, “It’s synonymous with supererogation.” I don’t know what it means, either.

After speaking some long word like that, Mother would go about her business, dropping big words here and there. Then the curious dog would slink off, embarrassed, while Mother’s crowd of admirers would wag their tails and grin with joy.

It was the same with phrases. Mother would drag home a whole phrase. If it had a grand sound, she would use it every day for six days, sometimes twice on Sundays. She would give it a different meaning every time she used it. Mother never cared about the true meanings of phrases. It just amused her to use them and have the other dogs ask her to explain.

Mother went so far as to recount whole stories and jokes that she learned from people. The only problem was that Mother never got the whole thing quite right. As she told the story or joke, she would leave things out. The story never quite fit together. At the end of it, she would roll on the floor with laughter even if she couldn’t remember why it was so funny. The other dogs would imitate her and roll on the floor with laughter, too. But they were secretly ashamed of themselves for not understanding the joke or story. Little did they know that the fault was not with them but with Mother’s bad storytelling.

You can probably see by now that Mother was a bit proud and silly. She had her good points, though. She had a kind heart and gentle ways. She never held a grudge and forgave everyone easily. She taught her children to be kind. We also learned from her to be brave and quick. She showed us how to face danger, not only danger to us but also to friends and family. As you can see, there was more to Mother than just her education.

My time with Mother, however, was not long enough. When I grew up, I was sold and moved away from her. She was brokenhearted. So was I. We cried and cried. She tried to comfort me as best she could.

“We were sent into this world for a wise and good purpose,” she told me. “We must do our jobs. Take our lives as we find them. Do our best to help others.”

Mother said that men who lived in this way received rewards in another world. We animals could not go to that other world, she explained. But if we always did the right thing, even without a reward, our lives would be worthy. And that was reward enough for us.

Mother had formed these thoughts from when she’d gone to Sunday school with the children. She had studied them well, for our good and for hers. Mother had a wise and thoughtful spirit, in spite of her pride.

As we said good-bye, Mother said to me, through her tears, “Remember, my pup. When there is danger, don’t think only of yourself. Think of me and what I would do. Let that be your guide.” Do you think I could forget her words? I could not.

After that, I never saw Mother again. I was driven a long, long way from the only place I knew as home. I arrived at a fine house. It was charming, with pictures, decorations, and beautiful furniture. Sunlight flooded every room. There was a lovely garden with many flowers and trees. I became a member of the family at once. They loved me and petted me. They kept my old name, instead of giving me a new one. My name was very dear to me, as it was given to me by my mother: Aileen Mavourneen. She got it from a song. It was a beautiful name, I thought, and so did the Grays, my new family.

Mrs. Gray was thirty, and so sweet and lovely. Sadie was ten and just like her mother. She had auburn hair in pigtails that trailed down her back. The baby was a year old, plump and dimpled. He was so fond of me. The baby pulled my tail and hugged me all day long, laughing as he did it.

Mr. Gray was thirty-eight. He was tall, slender, and handsome. He was a little bald in front, business-like, and focused. His features were perfect. His eyes sparkled with intelligence. He was a renowned scientist. I don’t know what that means. But, oh, my mother would have happily shown off that word in front of the other dogs. They would have felt so sad to be so uneducated. The best word, though, is “laboratory.” My mother could have saddened all the dogs with that one.

“Laboratory” was not a book, or a picture, or a place to wash your hands (like “lavatory”). The laboratory was quite different. It was filled with jars, bottles, and electrical things. Every week another scientist came and sat with the master. They used the machines, talked, did experiments, and made discoveries.

Often I came along and stood around listening. I tried to learn, for my mother’s sake. In loving memory of her, I tried to understand what the people were saying. It pained me that Mother was missing all this learning and that I didn’t understand a bit of it.

Other times I lay on the floor in my mistress’s workroom and slept. She gently used me as a footstool, which I loved. Other times I spent hours in the nursery. Sometimes I played with the baby. Sometimes I stood guard over him. Sometimes I would run and play in the beautiful garden with Sadie, until we were both tired. I’d nap in the shade of the biggest tree.

Or sometimes I would visit with the neighbor dogs. There was one dog who was handsome and courteous and very graceful. He was a curlyhaired Irish setter named Robin Adair, who was a Presbyterian, just like me!

The servants in our house were all kind to me and were very fond of me. So, as you can see, I led a pleasant life. I was the happiest and most grateful dog in the world. As I had promised my mother, I tried always to do what was right, to honor her memory and her teachings. I wanted to make sure I deserved the happiness that had come to me.

Then one day, my little puppy was born. I was now a mother! My heart was full and my happiness was complete. My puppy was the dearest little thing. His fur was smooth and soft and velvety. He had such little awkward paws, such loving eyes, and such a sweet and innocent face. It made me so proud to see how the children and their mother adored it. Yes . . . it seemed to me that life was just too lovely.

Then winter came.

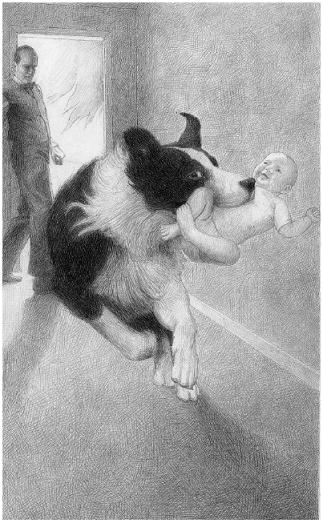

One day, I was standing watch in the nursery (actually I was asleep on the bed beside the baby’s crib, but I was still standing watch). The fireplace beside the crib had made the room warm and cozy, so we both slept very soundly. Now, the baby’s crib had a tent made of gauzy stuff that you could see through. The baby’s nurse was out of the room. The baby and I were alone in the nursery.

A spark from the wood fireplace caught on the gauzy stuff above the crib. The baby’s screams woke me. I saw the flames from the crib reaching up to the ceiling. I sprang to the floor and was halfway out the door when I remembered my mother’s words. I turned back into the room, reached my head through the flames into the crib, and dragged the baby out by his waistband. We fell to the floor together in a cloud of smoke. I grabbed him again and dragged the screaming little creature out the door into the hall. I was tugging away, excited and happy and proud that I had saved the baby’s life. That’s when I heard the master shout.

“Get away from him, you horrible beast!” he cried.

The master’s yelling scared me and I stumbled backward to get away from him. When I turned to run away, I twisted my left foreleg. The pain was terrible, but I kept running.

“The nursery’s on fire!” the nurse screamed.

The master rushed away. I limped on three legs to the other end of the hall. There was a dark little stairway that led up to an attic where old boxes were kept, and people rarely went.

I climbed up there and searched through all the dark piles. I hid in the most secret place I could find. I was afraid, even though I knew the master could not see or hear me. I was too afraid to whimper, even though it might have been a comfort. At least I could lick my leg, and that made me feel a little better.

For half an hour there was a lot of noise downstairs—shouting and rushing footsteps. Then there was quiet again for some time, and I was grateful. My fears began to go away. I was happy for this, for fears are far worse than pain. Then I heard a sound that froze my heart. They were calling me. They were shouting my name. They were searching for me!

Their voices were muffled and far away. But still, I was terrified. I heard them calling every-where— along the halls, through all the rooms, in the basement and the cellar. Also outside, farther and farther away, then back in the house all over again. I thought it would never stop. After hours and hours, the house grew quiet. There was only darkness, black as pitch, in the attic. I was no longer so very afraid. I fell soundly asleep soon after.

I awoke a few hours later. My leg didn’t hurt as much as it had before. So I came up with a plan to escape from the attic. I would creep down the back stairs and hide behind the cellar door. When the iceman came at dawn, I would slip out while he was filling the refrigerator with ice. Then I would hide all during the day, and start on my escape when it was night. I didn’t know where I would go, but I knew I never wanted to go back to my master. I was quite pleased with my plan, until I had another thought: What would my life be without my dear puppy?

At that thought, my whole plan fell apart. I saw, at once, that I must stay where I was. I would stay and wait and take whatever the master would do to me. I could not leave my puppy. Just then the calling started again. All my sorrows came back. I did not know what I had done to make the master so angry. But I knew whatever it was, he would never forgive me.

The people called my name for what seemed like days and nights. I was so hungry and thirsty. I was getting very weak, and I slept a lot of the time. Once I woke up in a terrible fright. It sounded as if the calling was right in the attic. And it was. It was a child’s voice. It was Sadie. The poor thing was crying. My name fell from her lips all broken. I could not believe my ears when I heard what Sadie was saying.

“Come back to us, oh please come back to us. Forgive us. It’s too, too sad without you . . .”

I interrupted her with such a grateful little yelp. The next moment, Sadie stumbled through the darkness. She shouted for her family, “She’s here! Come to the attic—she’s here!”

The days that followed were wonderful. Mrs. Gray, Sadie, and the servants all seemed to worship me. They couldn’t do enough for me. They made the finest bed for me. They cooked the most delicious meals for me. Every day friends and neighbors came to hear the story of my heroism (that was what they called it, and it means farming, I’m sure).

A dozen times a day Mrs. Gray and Sadie would tell the tale to visitors. They would say I risked my life to save the baby’s. Then the visitors would pass me around, petting and adoring me. I could see the pride in Sadie’s and her mother’s eyes. When the people wanted to know what made me limp, Sadie and her mother looked ashamed and changed the subject. It looked as though they were going to cry.

There was even more glory than this! The master’s friends came. Twenty of the most important people. They took me into the laboratory and discussed me as if I were an exciting discovery. Some said I was a wonderful dumb beast who had shown fine survival instincts. My master argued that I had acted far beyond that. I had used reason, and far better reason than many men he knew, including himself.

“I thought the dog had gone mad and was destroying the child,” he said with a bitter laugh. “But without this dog’s intelligence and ability to reason, the baby would have died.”

Master and his friends argued the point for quite some time. I just wished my mother could have known the grand honor that was mine. It would have made her proud.