One March morning, only months ago, I made breakfast for my daughters and walked them to school (my eldest held my hand so she could continue to read Ramona and Her Father as she walked), then rode my bike through the rainy streets of my neighborhood to swim laps in the pool; later, I sat alone in a gallery, gazing into photographs, colors all around me.

In the afternoon, I taught a class, trying to help the students with their writing, turning to and leaning on my own mistakes.

I checked my college mailbox before heading home: there, a pile of paper that I jammed into my pack, along with a copy of Shurtleff’s Audition, forced on me by a Theatre major who was certain it would clarify to me what I’d been saying in class. The book had a note folded into it, a list of page numbers I must read, and a star next to the very short third chapter:

3

Consistency

Consistency is the death of good acting.

Riding my bike home, I coasted down a long hill, thinking about what I’d told the students that afternoon—I said, “Momentum is everything, in a narrative. If you’ve ever ridden a horse, you know that when they see a hill coming they speed up, right before they reach it, so they can get to the top without straining. So it is with information—exposition, reflection, description, digression—in your storytelling. Something has to happen, to be promised, enough tension and anticipation and expectation, that you and your reader can easily, happily get over these hills of context.”

The explanation was clear enough, but, as usual, a simplification. There are all manner of horses, all sizes of hills.

At home, I opened a beer and, standing in the kitchen, pulled the papers from my pack. Amid the memos and junk mail was one hand-addressed envelope, which I opened. Inside, two pieces of paper—one just a scrap, torn along the top, the other whole.

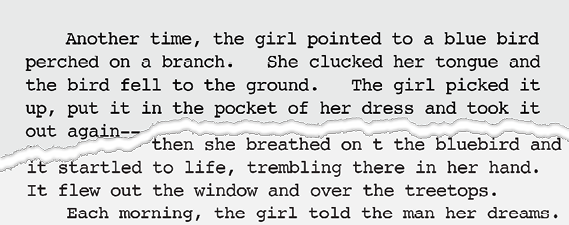

I read the story through again, then carried it down to my basement room and found the old notebook I needed. There, folded between Burchfield’s fire in the forest and the scrap of birch bark, was the first half of the story, the fragment that I’d found in Mr. Zahn’s house. The paper was torn right at the place where the new fragment began:

Upstairs again, I found the envelope, fallen under the kitchen table. There was nothing else inside; no explanation, no note; no return address. Yet when I read the postmark—Ephraim, WI 54211—it was as if Mrs. Abel were calling to me.