A pint of Belhaven Best settles.

In Britain’s North lies a remote country where sinister crags watch over lonely rain-lashed moors, where the winter sun rises lazily and spends just seven short hours drifting across the southern horizon, where kilted William Wallace spilled English blood, and where Robert Burns spilled glorious ink. A country, in short, that inspires many romantic ideas.

Romantic ideas swirl around the ales, too. People believe that the ales are made malty sweet because hops don’t grow that far north; that the beers have become caramelized from long boils over an open flame; that strong Scottish ales are smoky from peat-roasted malt; and the most famous Scottish ale is a titanic brew burly and thick enough to hold a spoon upright and sweet enough to dribble on toast. Yet these are all more myth than fact. There are distant kernels of truth to such legends, but the real story of Scottish ale draws on the country’s commercial and trade history—the part about Adam Smith, industry, and financial conquest.

In truth, Scottish beers don’t differ so much from their cousins to the south, but they were and remain more worldly and responsive to trends. If you want a barrel-aged British beer, a potent stout or spiky IPA, you’re more likely to find it in Scotland than down below the border. ■

SCOTS HAVE BEEN brewing beer for a long time. Archaeologists have found what might be evidence of not only brewing but also malting in Fife and the Orkney Islands dating to 4,000 to 6,000 years ago. Those early brewers were well north of the nearest hop plant (which in any case wouldn’t be discovered as a useful beer ingredient for thousands of years), so they spiced their beer with heather, meadowsweet, and other wildflowers. The case is not incontrovertible, but the weight of evidence suggests very early brewing—giving those ancient people bragging rights, along with the Sumerians, as the world’s first brewers. The Scots have been making beer ever since.

The country’s brewing history largely mirrors neighboring England’s. Through the Middle Ages, beer was a rustic, mostly homemade beverage, only incorporating hops as a spice well after they had taken root in continental recipes. But after centuries of slow change, Scotland’s brewing industry changed almost as rapidly as England’s at the start of the 19th century. Although the country may appear remote to folks in London—or even those in Yorkshire—its port towns tied it to the world. As in England, Scottish breweries industrialized and innovated. In fact, sparging—the now-universal practice of sprinkling water on the grain bed—was developed in Scotland.

There’s a persistent belief that Scottish beers were rough and rustic. For some reason, many Americans believe old Scottish ales would have been smoky because malting kilns must have been filled with clouds of peat smoke—as they were in the maltings of some distilleries. (It’s why American brewers began making smoky “Scotch” ales.) But even as early as the seventeenth century, Scottish brewers were firing their kilns with coke to reduce smoky flavors. Smoke may be fine in an Islay single malt, but it has been 300 years since it was appropriate in a Scottish beer.

Scotland was one of the most modern brewing countries in the nineteenth century. As breweries grew to become more impressive commercial concerns toward the end of the eighteenth century, the cities of Edinburgh and Alloa became brewing centers. This seems largely due to the hard water, which was similar to the mineral wells found under England’s Burton upon Trent. If there was ever a signature Scottish beer, it might have been Edinburgh Ale, a hearty beer tailored from that hard water. Made from 100 percent pale malt and served in tall, thin glasses like Champagne, it sounds much like Burton’s famous namesake ales. One contemporary called it “glutinous and adhesive” in 1852. Another description, from 1833, described it this way: “It is as clear as amber, and of the same colour; soft and delicious in taste; so strong, that a few glasses produce a slight intoxication, or inclination to sleep; and has a thin creamy top.”

Edinburgh was such a major center of brewing—by 1825 it had twenty-eight breweries—that it had earned the nickname “Auld Reekie.” The city, swaddled in a layer of black smoke, may not have been fouled solely by breweries, but the industry was a major contributor. Not only did the city’s breweries all have roaring fires powering their boilers, but many also malted and kilned their own grain, too, contributing further to the haze. Alloa, thirty miles west of Edinburgh on the banks of the Firth of Forth, was nearly as famous for its brewing industry. In the mid-nineteenth century, it was producing more barrels of beer every year than it had citizens. The beer from these towns was commanding premium prices in England, and production of beer doubled in Scotland between 1850 and 1870. Scottish ale was even famous beyond Britain. Writing in 1860, the French scientist Louis Figuier said it was “the strongest and best beer made in Great Britain. It is distinguished from all other domestic beers in its alcohol content, beautiful amber tint, and balsamic taste.”

A pint of Belhaven Best settles.

Scottish beer did feature a few idiosyncracies of method and ingredient. It was generally a bit less hoppy than English beer—but clearly by design. One of the long-held mistaken beliefs about Scottish ale suggests that the relatively less hoppy beers of Scotland got that way from want—hops just didn’t grow nearby. This plausible line looks less so in light of the number of ships leaving with Scottish ale and returning with English barley (which was better than the rough native strain known as Bigg barley). If they were importing barley, surely they could have imported hops as well—had they wanted to. Indeed, Scottish breweries competed in the IPA trade and made plenty of well-hopped beers.

Shillings and Guineas. Like English ales, Scottish ales were long priced based on how alcoholic they were. Also as in England, Scottish ales used a scale to represent this range. Rather than Xs or Ks, though, Scots used the actual price for a hogshead of ale in the mid-19th century—hence the classic 60 and 80 shilling ales, which you still see even today. It was an obvious way to do things, but the legacy is confusion.

There were a couple problems. Prices varied depending on the cask size—regular barrels were cheaper than larger hogshead casks. Since all beers were priced in shillings, it didn’t tell you much about what kind of beer was inside the cask—just its strength. A hogshead of 60 shilling might have contained a stout or a pale ale. Even more confusing was the occasional use of a different unit of currency, the guinea, to designate strength—for guineas went out of use in 1816 (and the fact that a guinea equaled a bizarre 21 shillings?—don’t ask). Fowler’s was still making 12 Guinea Ale 150 years after the coin’s last use. Fortunately, 12 guinea ales were being renamed in the twentieth century to the far clearer “wee heavy.” Clear, that is, once you know that “wee” referred to the small bottles they were sold in, and “heavy” to the strength of the beer, which was considerable.

Scottish breweries used sugar less often and seemed to favor less attenuated beers than the English. One of the enduring myths about Scottish ales is that long boil times caramelized the wort, but historian Ron Pattinson, writing in Scotland!, found absolutely no evidence of this when he scoured brewing logs of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. To the contrary, Scottish breweries used short boils—sometimes as little as an hour.

Scottish breweries made porters and stouts, not in great quantities, but consistently throughout the twentieth century. If there’s any argument to be made about a unique Scottish beer, these versions of porter and stout may be it. The deviations from English styles began in the nineteenth century, when grists featured higher proportions of dark malts than English porters. The attenuations were consequently lower—in some cases lower than 60 percent. Scottish breweries followed the English trend of making sweeter stouts in the twentieth century, but they took the concept to new heights. Most were under 70 percent attenuated, and about a third were less than 50 percent attenuated—an amazing number for a modern beer.

A final characteristic of Scottish ales was low fermentation temperatures. There was a range, but most breweries pitched their beers below 60°F (lower for higher-gravity beers), giving Scottish ales a more lager-like character and far less fruitiness than English ales. This dates back at least to the early nineteenth century, and is the only real point of continuity in Scottish brewing. Belhaven’s George Howell confirmed that yeast never used to be a significant factor in Scottish brewing. When he worked for Tennents in the 1970s and ’80s, it functioned as a de facto yeast bank for area breweries. Whatever yeast was on hand was fine because the temperatures were low enough that character varied very little by strain.

The structure of the Scottish industry was unique in one important respect, and this turned out to be very bad for the country’s breweries in the postwar period. Unlike England, where breweries were licensed to own their own pubs, in Scotland this was much harder. The effect was the inverse of England’s, where breweries developed fiefdoms of pubs in their local region. In Scotland, independent pubs were common, so breweries competed for tap handles. To boost barrelage, breweries sold farther and farther afield, becoming quite adept at export trade. By the end of World War II, Scottish breweries—despite producing a fraction of Britain’s beer—accounted for half of all British exports. Unfortunately, as the British empire collapsed, so did this lucrative market. With no local pub infrastructure to support them, many breweries watched their sales plummet.

The effect was massive consolidation (or “rationalization” to Brits). Breweries began buying each other out at fantastic rates. By the mid-1990s, there were only six breweries left making a total of twenty beer brands. Fortunately, that was the low-water mark. Craft breweries started opening up shortly thereafter, and there are now around 200 scattered across Scotland. ■

Bere, Bigg, or Bygg Barley. Scotland is home to a particular traditional or “landrace” barley called “bere” (pronounced bear). Its original source is obscure, but the Norse word for barley, bygg, suggests some Viking parentage. Yet the substantial genetic variation among bere varieties and their difference from Scandinavian barley stocks suggest that it predates the Vikings—and archaeologists think that Neolithic people were making beer by at least 2000 BCE.

In any case, bere is a family of barleys particularly suited to long days, short growing seasons, and low-pH soils—all adaptations that make it particularly suited for Scottish agriculture. Bere was used by Scottish breweries until the nineteenth century, but it was considered a poorer grade and was less efficient in the mash (so much so that it was even taxed at a lower rate). However, scientists have begun reexamining bere as a possible hardy strain resistent to blight. They’ve discovered that it has loads of enzymes and actually ferments quite well, which poses an interesting mystery: Why was bere abandoned? Perhaps to help the revival, Valhalla, from the Shetland Islands, makes Island Bere exclusively from the barley.

WALK INTO A PUB in Edinburgh and you’ll find a range of offerings typical of most British pubs—an assortment of lagers and light ales. Based on a first glance, you may develop the superficial impression that there’s not a lot of difference between the English and Scottish pub scenes. That’s true to a point—but only a point. Although they can’t always elbow their way into pubs, scores of Scottish breweries are making very interesting—and unusual—beers. The new guys have revived the tradition of strong ales by reintroducing wee heavies, the best versions of which are some of the world’s finest beers. But they’ve also gotten experimental—though usually in a very Scottish way. Some have experimented with pre-hop ales; others are availing themselves of local whisky casks and making barrel-aged beers. Still others are dabbling in interesting throwback styles like stout.

No review of Scottish ales would be complete without a mention of New World interpretations. American breweries have gotten into the act by inadvertently inventing a peaty style based on a misunderstanding of Scottish malting. American Scotch ales may not be traditional, but they have developed a devoted (if small) stateside following and are, at least nominally, “Scottish.”

Heather Ale. Although archaeologists believe that the first heather ales may have been made six millennia ago, in Scotland it is the ancient Picts who are remembered for brewing them. So famous were their heather ales that they have entered folklore. In the stories, the heather ale is more a metaphor for things lost—not only the rare elixir, but the Picts themselves, who carried their secret recipe to their graves. What’s fascinating is that, despite the legends, heather ale didn’t die out. It continued to be brewed noncommercially through the end of the nineteenth century. The botanist John Lightfoot wrote about residents of Islay and Jura making heather beer in the 1770s. Writing in 1900, folklorist R. C. Maclagan interviewed people who remembered drinking or making heather ale in the 1800s. It is certain that all these beers were made differently, but the lineage is impressive—from the Neolithic through the Pictish era all the way to modern-day revivals such as Williams Brothers’ Fraoch. Six thousand years of heather ale!

Among the ale family, the most popular are those that are still recognizably “Scottish.” These ales usually have characteristically Scottish names like 80 Shilling, St. Andrews Ale, or Flying Scotsman; they’re served in pint glasses and have a coppery hue; and they look like proper pints of bitter. So similar are they to the pub favorites of the country to the south that even the Scots don’t entirely know how to distinguish them. When I was speaking with Belhaven brewer George Howell, I asked what made these beers “Scottish.” It took him a long time to answer, and he hazarded that it might have to do with hops (less up north). But on the whole—not much difference.

They aren’t the same as bitters, but you have to look closely if you want to locate that special Scottishness. Howell mentioned hops, but—if you’ll allow an outsider’s perspective—it’s really the malt. Scottish session ales can be read as tiny treatises on the expressiveness of malt flavor. With reserved hopping, you can see the way soft, fruity esters play off a refined woodiness. You find all the classic malt adjectives in different brands—toffee, bread crust, walnut, biscuit—and yet they fail to capture the more evocative elements that spring to mind when you’re pondering these unassuming little ales. Once, sitting in an airport lounge, I ordered a pint of Stewart’s 80/- (their classic heavy) that brought to mind reeds swaying in springwater. Another romantic notion about Scotland? Possibly, but a pint or three of fine ale brings out poetic notions.

The most distinct element is the way they feel on the tongue. “Silky” is the only word that will do. Some of these beers aren’t even 4 percent, and yet they have a soft viscosity that caresses the tongue. The quality isn’t reserved for session ales—you find it in wee heavies, too—but it is illustrated best by them. Thin pub ales barely sustain you through one pint. A Scottish ale, with its quietly luxurious body, can easily sustain a night’s session.

The new crop of Scottish brewers bears some resemblance to American craft breweries: They are creative and improvisational, making aggressive, hoppy ales and strong, whisky barrel–aged beers on the one hand and re-creations of historic beers on the other. One of the most dynamic—and controversial—is Aberdeenshire’s BrewDog, a brewery nearly as committed to provocation as it is to brewing. Its range of beers is illustrative, though: two New World–hopped IPAs, a Scotch whisky–aged imperial stout, and a series of experimental beers in a line they call Abstrakt.

Yet in the famous brewing city of Alloa, Scott and Bruce Williams have gone exactly the opposite direction at Williams Brothers Brewing, brewing beers based on what might have been crafted a thousand years ago. Their flagship Fraoch is a heather ale, and they added other strange creations over time: beers made with elderberry, pine, gooseberry, and seaweed. Of these beers, Fraoch is the most interesting—a sweet, flowery beer that has inspired many imitators, particularly in the United States.

Perhaps the most interesting of the new breweries is Harviestoun in Alva, just up the road from Alloa. Founded in 1984, Harviestoun has a typical range of beers—shilling bitters and seasonals. In 2005, however, it launched a line of beers named Ola Dubh. Called strong ales—but looking a whole lot like stouts—they are aged in Highland Park Scotch whisky barrels. Americans have been using American whiskey barrels for some time, but Harviestoun is the first to take advantage of Scotland’s most famous beverage. Ola Dubh is thick and sweet, a perfect base for the smoky, peaty liquor infusion. Other breweries have followed suit, including BrewDog and Orkney. These are pure Scotland, and taste like they’ve been made for 200 years.

Many immigrants to the United States have received the same treatment: altered names, scrambled nationalities. A few generations down the line genomes wander some distance from their country of origin. This is the history of beer styles, of course. America melts more than national identity—it changes beers, too.

Scottish ales are a case in point. In their native land, they differ little from other British styles. In their Americanized form, they became peaty, often “perceived as earthy or smoky.” That description is from the American Homebrewers Association, one of the early vectors of misinterpretation. The romantic ideas crept in, as did the influence of Scotland’s other national beverage, whisky. Add the fact that American brewers were able to buy peat-smoked malt from companies like Simpsons that produce it for the country’s distilleries—and you have all the makings for a little reinvention.

Strong, malty, often peaty or smoky ales are now what Americans think of when they think of Scotland’s beer. As a consequence, these are the kinds of Scotland-inspired ales you’ll find in the United States. The nomenclature is a little blurry, but in the U.S., “Scottish ale” refers to cask-strength session beers, while “Scotch ale” refers to a fairly robust beer, seasoned with smoked malt. A couple popular smoky examples of Scotch ale are Pike Kilt Lifter, Odell 90 Shilling, and Samuel Adams Scotch Ale.

American and Scottish brewing intersect with wee heavies—or perhaps run in parallel. A wee heavy boasts a strength of between 7 and 9% ABV—not gigantic, but robust—perfect as an after-dinner ale. Many of the classic examples come from Scotland: Orkney Skull Splitter, Traquair House Ale, Belhaven Wee Heavy, and Broughton Old Jock. In truth, these beers don’t deviate much from other British strong ales—they’re malt-forward, rounded, fruity, warming, and very smooth.

American versions are—as always—more extreme. Not only are they more alcoholic, ranging from 8 to 10% ABV, but they are often heavier and more well-hopped. Of course, they also often have that smoke/peat note. Founders Dirty Bastard may be the country’s best-known wee heavy, and it’s made with a boggy underlay of smoked malt. At 50 IBU, however, it marks itself as definitively New World. Others of note are AleSmith’s Wee Heavy, Great Divide’s Claymore, Oskar Blues’s Old Chub, and Silver City’s Fat Scotch Ale. ■

THERE’S VERY LITTLE difference in the way Scottish and English breweries make beer—and even those differences are becoming less and less distinct. Historically, Scots fermented their beer at temperatures in the mid-fifties Fahrenheit, as much as 10°F lower than the English. Now the temperatures are closer to English fermentation temperatures, though still on the cool side. Unlike English ales, which are identified by soft fruitiness, Scottish beers don’t have much of an ester profile. Scottish ales also have the reputation of packing less hop punch than English ales, but beers like Caledonian’s Deuchars IPA make me doubt the claim.

Even though most now know better, many American breweries continue to use peat-smoked malt in their grists. This is what happens when customers get used to certain styles—for many American audiences, that smoky-peaty character has become a key marker of Scotch ale, even if it was invented in the States. Since the beers are relatively strong sellers for many breweries, it’s likely that these American interpretations will remain the standard. Of course, there’s a reason they’ve become a minor hit: They’re tasty. Since their introduction, breweries have learned to include just modest amounts of peat-smoked malt—it doesn’t overwhelm the beer. Instead, it offers drinkers just the suggestion of the Highlands. ■

WE’VE ALREADY DISCUSSED the wave of change happening among craft breweries in Scotland. If other countries offer any example, some of the types of beers these breweries make will filter into the mainstream market. Perhaps more important, they will begin to nudge drinkers in the direction of more adventuresome flavors so that even standard shilling-type ales may begin to exhibit higher gravities and hop infusions.

Scottish ales have long animated the imagination of breweries far away. The Belgians took a particular shine to Scottish ales about a hundred years ago and continue to make their own interpretations (beer styles drift as much in Belgium as they do in the U.S.).

The next great wave of Scotch ales hit North America in the 1980s with their peaty reinterpretation. In the manner of an artist looking through his early juvenilia, though, there’s now a sense of sheepishness in the United States about peaty Scotch ales. In fact, as a legacy to early mistakes, “authenticity”—beer made as close as possible to classic examples—has become an increasingly important marker of quality. The Great American Beer Festival has sequestered smoky Scotch ales in a separate category, perhaps trying to herd breweries back toward authenticity. Yet the peaty examples have a definite fan base—the world may have to reconcile itself to the idea of American Scotch ales for the time being. In terms of cultural imperialism, however, it’s not the most egregious case. Have you ever tried Scottish curry? ■

FINDING CHARACTERISTIC Scottish ales is something like taking a review course in English literature. There are so many different examples, the best one can do is dive in and start sampling. The following selection reflects four categories of Scottish ales: standard session ales of the type found in Scotland, unique expressions of Scottish brewing, wee heavies, and American Scotch ales.

LOCATION: Dunbar, Scotland

MALT: Pale, crystal, black

HOPS: Challenger, Golding

OTHER: Brewers sugar

4.6% ABV, 24 EBU

St. Andrews is a good place to start as a way of tuning your palate to Scottish brewing. It possesses the soft, gentle qualities that mark the tradition—almost like rainwater. A rounded, resonant ale perfectly characteristic of the Scottish impulse toward malt. In Belhaven’s beers you’ll find a very slight ester, which to my palate has the quality of rosewater. American breweries would do well to study St. Andrews, a beer focused entirely on malt; never, though, does it feel heavy or sweet. St. Andrews finishes with a satisfying crispness, luring you toward another sip.

LOCATION: Edinburgh, Scotland

MALT: Maris Otter, wheat, crystal, chocolate, carapils

HOPS: Challenger, Magnum, Tettnang, Styrian Golding

4.4% ABV, 18 IBU

This striking, deep amber beer is one of the finest Scottish ales on the market—though it is, unfortunately, only available on cask in Scotland. The nose is pure malt, at turns nutty and something like polished wood. Compared to the classics from older breweries, Stewart’s Scottish ale is hearty and rich. The body is creamy, but the palate is never too sweet.

LOCATION: Fort Collins, CO

MALT: Pale, caramel, chocolate

HOPS: Undisclosed

5.3% ABV, 23 IBU

Odell manages the nearly impossible by nailing every part of the equation. Its 90 Shilling is a lovely garnet-brown color, bright and scented with toffee, nuts, and an earthy spice. The beer’s brewed to American strength and has the concomitant heft, but is as smooth and supple as an Edinburgh ale.

LOCATION: Orkney, Scotland

MALT: Pale, chocolate, caramel, wheat

HOPS: First Gold, Golding

4.6% ABV

Somewhere between a mild and a porter, Dark Island is Orkney’s effort to put some color in Scottish ales. There’s a sweetness born of the darker malts, but esters, too—surprising for a Scottish ale—with the chocolate malts offering a bit of roasty balance. A creamy, supple beer with a hint of warmth for those long, cold winters.

LOCATION: Alva, Scotland

MALT: Pale, roasted barley, oats

HOPS: East Kent Golding, Fuggle, Galena

8.0% ABV, 45 IBU

There are actually five versions of Ola Dubh, but the difference among them is the age of the Highland Park whisky barrels in which they’ve matured. The base beer that goes into the barrels is something between an old ale and an imperial stout, with an original strength of 10% ABV. Harviestoun then chooses among five vintages of Scotch barrels—12, 16, 18, 30, and 40 years old. The younger barrels seem to contribute fewer whisky notes. The 12-year-old has notes of wood, pipe tobacco, and vanilla along with the rich chocolate of the beer, while the 30-year-old is thin and intensely whisky accented, sending the beer to the background. In the middle vintages, you might find notes of umami, sea salt, and an earthiness like mushroom or truffle.

Ola Dubh is Gaelic for “black oil,” and the name is apt; all five versions are extremely rich and creamy, attaining a viscosity rarely found in beers.

LOCATION: Alloa, Scotland

MALT: Pale, caramel, malted wheat

HOPS: None

OTHER: Heather, bog myrtle (sweet gale)

5.0% ABV, 1.050 SP. GR., 0 IBU

If you wanted to wax poetic, you could say this is the taste of ancient Scotland. Long before hops came to Great Britain, brewers were making beer with local herbs. Heather beer is a tradition as old as Scottish brewing. Does Fraoch taste like that ancient brew? Unlikely. Made with modern barley (not bere, the native precursor to domestic barley) and wheat, it has a smooth softness characteristic of modern Scottish beers. But it is easy to see how heather and sweet gale might have delighted ancient palates. They offer a sweet, herbal, and slightly minty counterpoint to the malt.

LOCATION: Innerleithen, Scotland

MALT: Pale, roast barley

HOPS: East Kent Golding

7.2% ABV, 1.066 SP. GR.

Traquair House has been making strong, elegant beers for decades and is principally responsible for making strong ales popular once again; Traquair’s ales are stronger and deeper than most. House Ale is a woody, dark amber color that has a perfumy nose made entirely of malt with notes of caramel, raisins, and brown sugar. The body is smooth and rounded, but also crisp. This is a lush, lovely beer.

LOCATION: Orkney, Scotland

MALT: Pale, caramel, chocolate

HOPS: East Kent Golding

8.5% ABV

A nod to the bloody nickname for the Viking seventh earl of Orkney, Thorfinn Einarsson, “Skull Splitter” doubles as a reference to the boozy “crackskulls” of old. This is a manly ale that announces its heft in the boozy, fruity nose, and keeps you thinking of it as you find rum and plenty of warmth. Lots of complex esters—dates and figs, principally—and rich caramel treacle round out the beer.

LOCATION: San Diego, CA

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

10.0% ABV, 1.096 SP. GR.

American Scotch ales provide a real acid test for a person’s palate—rare is the person who is indifferent toward them. AleSmith’s offering may be the best peace-maker between the two camps. While it’s very heavy and sweet, it doesn’t quite taste like smoked porridge in the way some do. There is a fresh baked-bread nose, which picks up some notes that transmute it to something approaching gingerbread. Peaty more than smoky, with a stout-like color and even a touch of licorice. With its tobacco head and hot-chocolate body, it is a most comely beer.

LOCATION: Seattle, WA

MALT: Pale, caramel, Munich, carapils, peat-smoked

HOPS: Magnum, Golding

6.5% ABV, 1.064 SP. GR., 27 IBU

A beer notable for its reserve, Kilt Lifter is not a thumping peat bomb, nor is it overly treacly. Although there is a bit of peat underneath the malt, this beer does a good job of nodding toward Edinburgh. The nose is almost like rye bread—a spicy, earthy breadiness, and on the palate, the deep amber beer is nutty and sweet.

LOCATION: Grand Rapids, MI

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

8.5% ABV, 50 IBU

A rare American version that plays it mostly straight, this nearly-brown ale is a caramel confection balanced by a hint of nuts. It’s far thicker and creamier than Scottish examples, but a recognizable descendant of ales like those made at Traquair House.

IF YOU HAD TO CHOOSE ONE BREWERY TO REPRESENT THE HISTORY OF SCOTTISH BREWING, YOU COULD DO A LOT WORSE THAN DUNBAR’S BELHAVEN, THE OLDEST BREWERY IN THE COUNTRY. THE SITE IS LOCATED NEAR BARLEY FIELDS AND SITS ON TOP OF EXCEPTIONAL WATER—TWO INGREDIENTS THAT HAVE FUELED SCOTTISH BREWERS FOR MILLENNIA. BENEDICTINE MONKS SETTLED THERE IN THE TWELFTH CENTURY, LATER BREWING AND DISTILLING WHISKY. JOHN JOHNSTONE BUILT THE FIRST COMMERCIAL BREWERY THERE IN 1719—HIS ORIGINAL BUILDINGS ARE STILL A PART OF BELHAVEN—AND HIS FAMILY ADDED AN ONSITE MALTINGS IN 1814. AFTER A FIRE IN 1887, THE NEW OWNERS EXPANDED THE BREWERY. THESE STRATA OF CONSTRUCTION AND CHANGE MAKE UP THE MODERN BELHAVEN BREWERY, THOUGH THE CHARACTERISTIC OLD MALTINGS WERE CONVERTED TO OTHER PURPOSES IN THE EARLY 1970S.

By the time Belhaven discontinued malting, the Scottish brewing industry was in complete crisis. Scores of breweries had gone out of business, and the remaining few were hanging on by their fingernails. Belhaven passed from family control in 1972, but did manage to stay independent and had the good fortune to hire George Howell, who became head brewer in the 1990s. In the twenty years that Howell has been at the brewery, annual production has risen from 29,000 U.K. barrels (which translates to 40,000 of the smaller U.S. barrels) to 130,000 barrels (180,000 U.S.). During that time, Belhaven has modernized and evolved, a clear reflection of the trends in Scottish brewing.

A seal marks the brewery’s age.

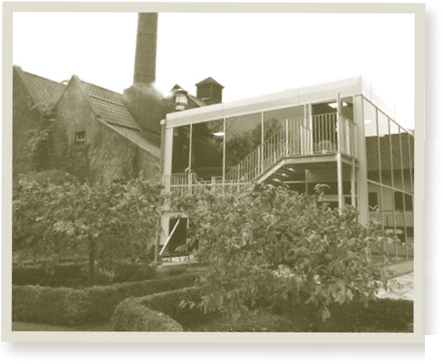

The new brewhouse stands out at the old brewery.

The beautiful old mash tun is still on site.

The flagship is Belhaven Best, a 3.2% beer sold cold and sparkling from a keg (not on cask). Scotland took to lagers decades before England, and cask ale was all but abandoned. Belhaven Best, nutty with malt yet crisp and effervescent, is a fusion of the past and present. It’s the bestselling kegged ale in Scotland and brewer Howell is unambiguous about what it means to the brewery: “Without Belhaven Best, we would not be here.” Best is a Scottish beer for Scottish drinkers.

If this seems miles removed from the idea Americans have of Scottish ales, that’s because it is. Yet there’s another side of Belhaven consisting of sessionable “Scottish-style” ales: 80 Shilling, St. Andrews, Robert Burns Ale, and Scottish Ale. These can be found in bottles or on cask and they conform more to foreign expectations with their silky maltiness. I find a rainwater freshness in them, and sometimes even a hint of rose blossom. They are also closely in keeping with the standard pub ales found throughout the rest of the island—British ales in the British tradition.

Scottish brewers have never been insular in the way English brewers are; they export a substantial amount of beer and are sensitive to foreign markets. Belhaven is no different. They offer plenty of beers for foreign palates, including a stout, a wee heavy, and an IPA. Scottish Stout is a booming 7% ABV beer that has a lush depth of malt character and is hearty and creamy (and, truth be told, would be perfect on a dark, cold Dunbar night—too bad it’s only sold abroad). Their Wee Heavy, robust by Scottish standards at 6.5% ABV, is thick and sticky. And their Twisted Thistle stands as one of the most hop-forward IPAs in Great Britain. One of the reasons I was drawn to Belhaven was the Twisted Thistle, but Howell concedes that he prefers less hoppy beers. It’s a Scottish beer for American drinkers.

Although these three spheres are aimed at three different constituencies, the beers are all quintessentially Scottish. They have Scottish pale malt as their base. The hops are principally British-grown Challenger and Golding. Many of their beers have a dab of sugar to give them a crisp finish. And they are fermented cool with a strain of yeast that’s only about twenty years old—“Nobody knows precisely where that yeast came from,” Howell admits. This is typical—Scottish beers aren’t brewed to pick up esters. They’re almost as lean and clean as lagers.

In 2005, the large English brewery Greene King bought Belhaven. Unlike many of Greene King’s other acquisitions, Belhaven was targeted both for its facility and its health. It made strategic sense by giving both breweries access to pubs in the others’ countries. With the recent shuttering of many Scottish breweries, the partnership has been crucial to keeping Belhaven in business. “I think that the truth of the matter is that without Greene King coming in, we might not be here,” Howell says.

Unusually, Greene King left brewing operations in Dunbar. It looks like a wise decision: If Scottish breweries learned anything from the massive consolidation of the twentieth century, it’s that “brands” alone don’t sell beer locally. “I think it’s very important to have a brewery in Scotland. Scottish people are … patriotic, as are most people, yeah? It would not work for Belhaven Scottish products to be brewed down south and sold in Scotland.”

Head brewer George Howell in the new brewhouse

In 2011, Belhaven built a new brewhouse and replaced its old mash tun and whirlpool. Since the country’s historic preservation agency, Historic Scotland, would not allow substantial alterations to the venerable old building, the brewery created a gorgeous steel-and-glass structure in the courtyard next to the former brewhouse. Immediately behind the new space is the old stack where smoke once billowed blackly into the gray skies. It’s a nice metaphor for a successful Scottish brewery: Modernization and adaptation are critical, but breweries can never forget where they came from.