Schlüssel Brewery in Düsseldorf is one of many in the altstadt that beckons to visitors.

Cologne and Düsseldorf. They are described as rivals, these two cities of the Rhine, and they make much of their competition. “We don’t say the name of that town here,” a smiling brewer from Cologne said of Düsseldorf. But no two cities are more like each other, or more different from every other great brewing city in the world. As it is hard to imagine a Picasso without a Matisse, it is hard to think that either of these two cities’ brewing traditions could have been born in isolation.

In the remarkable altstadt (old town) of Cologne, you can spend days popping in and out of breweries and pubs—perhaps also spending an hour or two to visit the cathedral, museums, or river—and find in each one a waiter with a tray of identical cylinders of golden kölsch. In Cologne, every pub serves this beer, every brewery makes it, and you will have to look hard to find anything else.

Düsseldorf is just a half-hour north by train, and it too has a remarkable altstadt. There you’ll find breweries and pubs stacked on top of one another, and you can spend days visiting them, too (though you might visit the river, museums, or go shopping in the Königsallee neighborhood). In the breweries and pubs of Düsseldorf, you’ll see waiters with trays of identical cylinders of deep copper altbier. Every pub serves this beer, every brewery makes it, and you will have to look hard to find anything else. These rivals may not be identical twins, but fraternal, surely. ■

HOPPY ALES are nothing new in northern Germany. It was, in fact, where they were born. Until sometime probably in the twelfth century, beer was still made exclusively with a spice mixture called gruit. Spices may have helped balance beer, but they didn’t preserve it—and it was brewers in the Hanseatic trading city of Bremen who first realized that hops would. “Bremen beer” made its way to other German towns (some, like Hamburg, appropriated it), where other brewers learned what those from Bremen knew: Hopped beer would last longer than gruit beer, which survived only days before souring. Because it lasted longer than local beer, even when shipped from leagues away, Bremen beer made its way out into the world—to Scandinavia, the eastern Baltic, the Low Countries, and Great Britain. It sailed around the region, too. One of the destinations for Bremen beer was the towns along the Rhine, the region that would come in future centuries to be most associated with hops.

As hopped beers spread across what is now northern Germany, brewers started hearing about a kind of cold-aged beer made in Bavaria. Northern breweries experimented with it, but the climate was milder there and beer spoiled more easily. The danger of making bad beer was strong enough that in 1603, the Cologne town council outlawed the use of bottom-fermenting yeasts, codifying ale brewing. So while Bavaria developed lagering techniques, breweries in the north continued to make a dazzling constellation of different top-fermenting beers.

Early writers catalogued all the beers brewed in different towns in the north—scores of them. They ranged from low-alcohol beers mostly free from sourness to low-alcohol lactic beers to heavy, sweet beers, some alcoholic, some not. The beers that would become kölsch and altbier appear to have come from different lineages. The kölsch line is the clearer of the two. One of the main types of northern ales was bitterbier brewed in Westphalia and along the Rhine River. By the turn of the twentieth century, descriptions sound an awful lot like kölsch.

Altbier’s history is a little more obscure. Almost every writer on the subject points to the word alt and the fact that ales predate lagers, and leaves it at that. Well, true—but that could be said for any of the German ales. Is modern alt’s ancestor a darker version of the bitterbier that was brewed more prominently twenty-five miles to the south? Or is it more closely related to a heavy, alcoholic brown beer from Dortmund fifty miles to the east, also called altbier? That beer, which was at other times called adambier, was sour and more like English porters of the day. Even Münster, another forty miles north of Dortmund, had a local altbier. (That beer is a less likely ancestral candidate—it was also sour, but golden, and lightly hopped to boot. Three strikes against Münster.) The most likely reading is that “old beer” doesn’t refer to style, just the broad category of prelager beers made throughout the region.

Brauhaus Früh, just steps from the famous Dom, in Cologne

Kölsch and altbier have been beset by trying circumstances for well over a century. The first barbarian at the gate was lager, riding the exceptional success of pilsner and sweeping up from Bavaria. Ale’s heyday ended around 1870, as lagerbier overtook it in terms of overall production. By the end of the century, not only were top-fermenting beers losing market share, they were actively in decline. The second unfortunate event was war. In World War II, both cities were targets of massive Allied bombing raids and reduced to rubble. After the war, brewers rebuilt, but kölsch and altbier were isolated styles and production steadily shrunk. In 1980, the two controlled over 10 percent of the German market, but by 2008, they had a mere 3 percent.

One Beer to Rule Them All. Superficially, the idea that in Düsseldorf they drink altbier and in Cologne, kölsch, seems like a reasonable one. But if you think about it for longer than three minutes, the concept is insane. We live in a market economy; new is exalted, variety demanded. Yet walk into one of the atmospheric pubs in Cologne—it’s true in Düsseldorf, too, but especially so in Cologne—and you are offered a binary choice: yes or no. The drink is kölsch and your communication to the waiter only involves a welcoming nod or abjuring shake of the head.

This is remarkable. The breweries of Cologne sell almost their entire production to people living within fifty kilometers of their mash tuns. They have to: Outside that tiny range (except for the very small amounts exported by a couple of the companies), people don’t drink it. Equally as amazing: Within the kölsch heartland there are no intense rivalries between breweries, no tub-thumping for the “true” or “original” kölsch. The city maintains a virtuous symbiosis, a gentleman’s agreement, and the brewers brew, and the drinkers drink, just one beer. Kölsch is king, but only in Cologne.

Although alt and kölsch are still widely available in their hometowns, breweries fret as they watch annual production decline. And this points to a bleak irony in the fates of these two beers. By being lashed firmly to the identity of their home cities, they managed to create a native base in which they could thrive for decades while other styles petered out. But now, as locals fail to drink enough to keep production up, brewers in Düsseldorf and Cologne have nowhere else to turn. The decline hasn’t been helped by a national trend away from draft beer sales; both alt and kölsch depend on pub consumption (about half of all the sales, twice the national average) to keep barrelage stable. For obvious reasons, these trends worry breweries. ■

IN CITIES FEATURING single styles of beer, breweries distinguish themselves by making their beers a little differently from the place down the road. Drinkers from other cities may lack the discernment to appreciate these differences, but they’re there. In fact, altbier and kölsch allow for fairly broad interpretation.

At first glance, kölsches seem to be doing a fine pilsner impersonation: They’re pale, clarion gold, and topped by a snowy head. Light-bodied as well, they’re very easy to drink and go down with a clean, crisp finish. All quite pilsnery. There are subtle differences, though. They do have a bit of yeast character if you look for it, a fruitiness so delicate it’s difficult to specificy—pear? Honeydew? In Cologne, the kölsches have a noticeable mineral, club-soda quality that heightens hopping and gives it an herbal twist. Whereas pilsners tend to dryness, in kölsch you find a softer, creamier center.

These are the general characteristics. In the particular, the breweries of Cologne take the three main elements—light hopping, soft, gentle fruitiness, and a crisp finish—and find their emphasis. Gaffel is not only the hoppiest, but the hops are the most distinctive, herbal with oregano and black pepper. Reissdorf, by contrast, plays more to malt sweetness. Früh has a tangy yeast that is almost lemony, and boasts the most assertive malt flavor. Pfaffen uses grassier hops, plays down the yeast, and produces the beer closest to pilsner. Outside Cologne, interpretations are more varied, especially in the U.S. Many are stronger and hoppier, but also less delicately complex. American breweries often add a touch of wheat to their kölsches and lack the fidelity to clarity you find in Cologne.

Alt appears to be a simple enough beer. Two or three kinds of malt, two or three types of hops, all put together in the usual way in the brewhouse and aged for a month in conditioning tanks. And yet, it is extremely hard to reproduce outside Düsseldorf. American breweries, adept at re-creating nearly any beer in the world, almost never do justice to altbier—I’ve had good and tasty American alts, just none that fooled me into thinking they were from Düsseldorf.

Alts are said to be a bitter style, but that’s misleading. Their most important quality is actually the downy softness of the malt. True, hops buttress the malt, but they’re not purely bitter. They instead spice alts with a woody, peppery flavor. As with kölsches, altbiers also have a mineral spine, a quality rarely reproduced outside the city since it’s tied to the area’s water source. I also found a caramel flavor that suggested the malt had been scorched by an open flame in a couple of the Düsseldorf alts. There can be quite a bit of variation in these elements, but the essence of the style is lost without them.

Kölsch-Konvention. In the mid-1980s, the breweries of Cologne gathered to discuss how to protect their business and promote the city’s signature beer. What emerged from the Kölsch-Konvention was a mission statement of sorts—and is the reason kölsch is such a fixture now in Cologne. At the time there were twenty-four signatories to the charter, and they strictly defined kölsch as a pale, top-fermented beer. It must be “hop-accented” and filtered, brewed within a gravity range of 11° to 14° Plato (1.044 sp. gr. to 1.053 sp. gr.), and served in a 20 cl stange glass. Additionally, Kölsch must by law be brewed within the Cologne metropolitan area. After Germany joined the EU, kölsch was given a Protected Geographical Indication—a legal designation for products coming from a particular defined region that are made in a particular defined way. North Americans don’t pay a lot of attention to the rules of appellation, but within Germany the only kölsches you’ll find will have been brewed in the city of Cologne.

Three local alts offer a survey course in how breweries can emphasize different qualities of their beers while retaining their essential alt-iness. Schlüssel is the least hoppy of the three, the softest, and the one in which the crisp, hard water is most evident. Uerige is at the other end, with the most assertive hopping, no caramel, and only a touch of hard water. In the middle is Füchschen, the most caramelly but also lively in hopping. In each case, the softness of the malt is a constant. When re-creating alts, Americans take the idea of hopping too far. It’s true that Düsseldorfers don’t use late-addition hops, but that doesn’t mean they’re trying to give the beer too much bite. If you start from the place that alts must buff the tongue in cottony malts, the constraints on hopping are clear.

There is also a tradition of brewing stronger, special occasion alts as well. The most famous is Uerige’s Sticke, released just twice a year. That beer is a slightly stronger version of the regular alt, but what makes it special is a dose of Spalt hops in the conditioning tank that produce a bouquet redolent of a forest floor. Füchschen makes a special alt called Weihnachtsbier released on Christmas Eve, and Schumacher produces Latzenbier for release on just one day in March, September, and November. ■

At the Füchschen Brewery in Düsseldorf, you will find not only a caramelly, lively alt, but a cozy pub buzzing with activity.

THERE IS AN OPEN, vigorous debate about whether kölsches and alts are ales or lagers. Kölsch and alt are foremost obergärige beers, that is, top-fermented. In other countries, people refer to beers of this type as “ale,” but Germans relate to their beers differently. With obergärige beers, brewers skim yeast off fermenters—the top-fermenting part. Germans relate to the yeast’s behavior more than its effect on beer, which is much subtler than elsewhere, where esters add baskets of fruit flavors and shakers of spice. For this reason, it used to be common to see these beers called obergärige lagerbier—top-fermented ales that have been conditioned, or lagered, in tanks. In their Teutonic manner, Germans have given it a perfectly precise term—but one that mostly confuses people from elsewhere. But things may be changing. At Reissdorf, brewer Frank Hasenkrug emphasized the fruitiness of the beer and when I mentioned the concept of a lagered ale, he disagreed: “It’s an ale.”

German ale brewers are used to being misunderstood. They can’t affiliate their beers with the much fruitier ales from abroad, but neither do they agree with foreigners who think their beers are “lager-like.” They do not use foreign ales or local lagers as benchmarks. Their beers are just as they should be—a touch fruity, soft, full, and refined. They get their fruitiness from warm fermentation, anywhere from about 62°F (Gaffel, Schlüssel) to 70°F (Uerige). These temperatures aren’t warm enough to produce vivid esters, but they are noticeable. Lagering, usually three to four weeks at near-freezing temperatures, helps keep German ales in check and allows the beers to develop their characteristic smooth, refined lines.

In Cologne, waiters carry handled trays with glass-size recesses.

The malt bills are simple and straightforward—a base of pilsner malt with a dash of Munich to enhance the golden color in kölsch, and darker Munich or cara malts for color (but never roastiness) in alts. Some breweries sprinkle a dash of wheat into their grists—perhaps 10 percent. The hop schedule is no more complex—peppery German hops are favored, though some breweries use high-alpha varieties like Herkules in the bitter charge, while others prefer aroma hops throughout.

Water in Cologne and Düsseldorf is hard, and every kölsch and altbier I sampled that was brewed in those cities had a mineral stiffness. In some cases it was slight, but it is a definite marker of place. The best alts and kölsches rely on this quality to assist in the overall sense of crispness that is a hallmark of Rhineland ales. ■

NEITHER OF THESE types of beers, fixed so firmly to the banks of the Rhine, would seem to be a likely candidate for production beyond their cities. For altbier that has definitely been the case. Only a handful of breweries outside Düsseldorf feature an alt as a regular part of their lineup, and it is rare to find in stores or pubs. Uerige has maintained a regular U.S. importer, but other brands are less reliable. Where American breweries have dabbled in alts, they tend to be boozier and hoppier—often referencing sticke beers, a stronger version of altbier.

Kölsch is another matter. For some reason, foreign breweries dabble in this style more often. There aren’t a huge number of all-season, American-brewed kölsches out there, but many breweries release a version for the summer months. Goose Island, Harpoon, Alaskan, and Saranac all make well-known summer kölsches. A few breweries, like Schlafly, Coast, and Chuckanut, do offer them year-round. With very few exceptions, breweries make kölsches straight up, with standard ingredients and at standard strengths and bitterness. Many brewers, having visited Cologne, want to honor and protect the tradition, so experimentation is the exception. ■

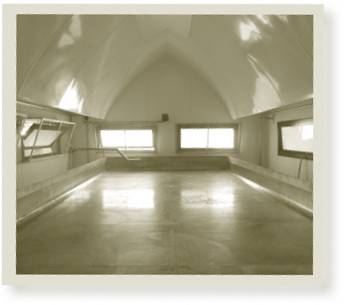

The Drinking Ritual. The hausbrauereien (brewpubs) of Düsseldorf and Cologne are, to an American’s eyes, colossal affairs. Some, like Früh or Schlüssel, have ballroom-size halls, while others, like Uerige, are honeycombed into smaller rooms that create a cozier vibe. In the evenings they begin filling up, and you may find yourself sharing a table with strangers. No matter—everyone’s there for the same thing: beer. Food, maybe, but definitely beer.

The waiters in both towns are known as köbessen, and in Cologne they carry trays with stange-size recesses—reminiscent of communion trays. (Some hausbrauereien have stained-glass windows, which enhances the ecclesiastical feel.) Düsseldorf köbessen carry regular trays, but they’re often packed densely with groves of slender little becher glasses (the same kind of glass, but—possibly to tweak Kölners—they’re a little larger). In both cities, the ritual is the same. Once you order a beer, your köbe will keep an eye on your glass. Periodically, he’ll make a pass through the room with a fresh tray. If your glass is less than a quarter full, he’ll drop a fresh one on the table and tick your beer mat (coaster) with a line.

In Düsseldorf, the glasses are a quarter-liter, but they’re only a fifth of a liter in Cologne. Some new arrivals take umbrage at the small portions, but it’s not accidental. Both altbier and kölsch are delicate drinks, at their best when they’re chilled to the right temperature and sparkling fresh. Over a session of drinking, you’ll never be long with a warming, flattening beer—very soon a fresh, chilled, bubbling beer will arrive at your table. When you’re ready to leave, you can place your beer mat on top of your final glass—though this isn’t strictly necessary. Uerige’s Michael Schnitzler said, “You can do this, or you can talk to the server. It’s also a good way.” Maybe so, but the ritual is what makes the experience so much fun.

I RECOMMEND tracking down kölsches and altbiers brewed in their home cities—despite the rarity of these beers—as a first step in understanding them. That ineffable character that makes them kölsches and altbiers is rarely found outside the Rhineland. But many foreign-made examples are worth trying for their own sake.

LOCATION: Düsseldorf, Germany

MALT: Pilsner, Cara-Munich, Carafa roast

HOPS: Spalt, Hallertauer Hallertau, Perle

4.7% ABV, “ALMOST 50” IBU

A frothy, fresh dark amber beer that vents largely the aromas of malt—wood and bread. Those aromas carry through in the taste as well, even though the sprightly German hops add a current of herbal spice stiffened by water minerals. It is rich but light, one of the most flavorful beers you’ll find under 5% alcohol.

LOCATION: Düsseldorf, Germany

MALT: Pilsner, Cara-Munich, Carafa roast

HOPS: Spalt, Hallertauer Hallertau, Perle

6.0% ABV

Sticke is not a huge departure from Uerige’s regular altbier, but the dry-hopping adds quite a bit of aroma and seems to heighten the sense of bitterness as well. This is a beer Americans can love, with caramel malt richness, strength, and layered spicy hopping, all wrapped up in a soft pillow of malts. One of the world’s great beers.

LOCATION: Düsseldorf, Germany

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

4.5% ABV

Füchschen’s alt is slightly lighter in color than Uerige’s, and perfectly bright. Although the hops are less bitter, they frame the beer prominently and have a clean, noble-hop spiciness. Underneath, the malts are lightly sweet with caramel and rounded.

LOCATION: Cologne, Germany

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

4.8% ABV, 1.044 SP. GR., 26 IBU

Gaffel is known as Cologne’s hoppy kölsch, and it is the most bitter. But more than that, it is complex, with an aroma reminiscent of green herbs. The flavors tend toward oregano and black pepper, and they gather around the soft malts to deliver a satisfying, crisp finish. Americans, fond of bold tastes, tend to gravitate toward Gaffel.

LOCATION: Cologne, Germany

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Hallertau, Tettnang

4.8% ABV, 1.046 SP. GR., 18–25 IBU

While Gaffel may be the hoppiest kölsch, Früh has the most yeast character. It is a delicate, complex beer, with crisp, tangy yeast character and a flavor that bends toward lemon. The malts are sweetly bready, and although Früh’s is a low-key kölsch, it may be the most accomplished.

LOCATION: Cologne, Germany

MALT: Pilsner, Munich

HOPS: Herkules, Perle

4.8% ABV

Reissdorf, the most readily available kölsch in the United States, is a mild (that is, less hoppy) version. Reissdorf finds balance among the elements of gently sweet malt notes, mineral crispness, and light hopping. The elements are best appreciated when you can enjoy three or four stanges. Sadly, kölsches don’t travel especially well, and their liveliness is often lost during shipment across the Atlantic.

LOCATION: Hood River, OR

MALT: Pilsner, Munich

HOPS: Perle

5.2% ABV, 40 IBU

Double Mountain more or less plays this beer straight—German malts and Perle hops—and many of the elements even create a kölsch-like balance. The crisp, grain-y malts support a subtle fruitiness and harmonize wonderfully with the black pepper spice of the hops. But there’s no mistaking which country it was brewed in—each one of these flavors is American-bold, especially the bitterness.

LOCATION: Houston, TX

MALT: Pale, malted wheat

HOPS: Hallertau

4.9% ABV, 1.045 SP. GR., 20 IBU

One of the American brews that most closely resemble those from kölsch’s home city, Fancy Lawnmower has a light graininess and dry crispness that reminds me of Cologne’s minerally water. The hops are floral but have a hint of lemongrass. An excellent kölsch if you can’t manage the trip to Germany.

German Cask Ale? In both Düsseldorf and Cologne you are liable to see kölsch and altbier served from a cask sitting on top of the bar. In some cases, the cask will even be wooden (especially in Düsseldorf). But don’t be fooled—this is more a matter of presentation than preparation. Uerige’s owner, Michael Schnitzler, described the practice: “It is just the traditional style of presenting the beers in a nice way. We tap it manually and then we put the barrel on the bar …. But there is no fermentation; there is nothing for the taste.” The beer stays in the casks only a short time, and the wooden barrels are lined so the contents aren’t exposed to either wood or oxygen.

Nevertheless, people take the barrels very seriously. All the wooden casks at Uerige are bound in metal bands painted red. This wasn’t always the case; Uerige used to have some that had green and yellow bands. Over time, customers developed the idea that the beer from barrels with a red band was superior. “Nobody knows why,” Schnitzler said, laughing. “The regular customers, they saw the barrels with the green ring on it and said, ‘Oh no, we cannot drink this one.’” Uerige had to paint them all red.

NAME A BREWERY THAT STILL USES A COOL SHIP, A BAUDELOT-STYLE DRIP CHILLER, AND OPEN FERMENTATION, AND SERVES ITS BEER FROM WOODEN CASKS AT THE BREWERY. NOW, NAME THE BREWERY IN GERMANY THAT DOES ALL THOSE THINGS. UNTIL MY EYES FEASTED ON THESE WONDERS, I WOULDN’T HAVE BELIEVED IT MYSELF, BUT THERE IS SUCH A PLACE AND YOU CAN VISIT IT THE NEXT TIME YOU’RE IN DÜSSELDORF. THE BREWERY IS ENTWINED IN A GORGEOUS, LABYRINTHINE PUB THAT WRAPS ITSELF INTO NOOKS AND POCKETS AROUND THE FERMENTERS, BREWHOUSE, AND OTHER EQUIPMENT. THERE ARE HOP WREATHES ON THE WALLS, STAINED GLASS OVER THE WINDOWS, WOODEN CASKS ON THE COUNTER, AND SCORES OF PEOPLE SITTING WITH SMALL GLASSES OF ALT IN FRONT OF THEM. EXCEPT FOR THE ODD CELL PHONE GLOWING IN THE SHADOWS, WITH A VISIT TO UERIGE YOU COULD BE STEPPING BACK IN TIME.

The vessel used to cool wort at Uerige—the first step in their traditional brewing process

It’s surprising to learn that Uerige isn’t all that old … for Germany. It dates only to 1862, when a brewmaster named Wilhelm Cürten bought the property and converted it from a wine tavern into a brewery. Cürten was apparently not much of a people person, leaving the brewery only on Sundays for church. They called him “grumpy Wilhelm,” and the name stuck—in the local dialect, the word for grumpy was uerige. (Pronunciations vary, but locals seem to start out with a sound halfway between oor and err that comes out in a long exclamation, followed by a half-voiced, short i as in pick, and a clipped guh to finish things off.) The brewery passed through four more owners until Christa and Josef Schnitzler bought the place in 1976. The Schnitzler family still runs Uerige, though it is Weihenstephan-trained son Michael who now guides activities.

The surprises continue when you learn that the brewery has recently been expanded and that Schnitzler added a distillery. Of course, the expansion only added capacity to the brewery, and the whiskies come from Uerige’s own beer recipes. Schnitzler is not averse to changing his business, but the beer is sacrosanct. In Germany, “we lost the beer tradition,” he told me. “We lost the typical way of brewing. Altbier—it means it is brewed in an old way, the traditional way.”

Uerige takes tradition more seriously than nearly any brewery in the world. It still only brews one kind of beer, though it does have unfiltered and stronger variations. The process is uncomplicated but precise. The grist includes just three malt varieties, and the brewery adds two hop additions early in the boil, a blend of Hallertauer Hallertau, Spalt, and Perle hops. Only whole hops, of course—the traditional way. From the kettle, the wort goes on a strange journey back in time.

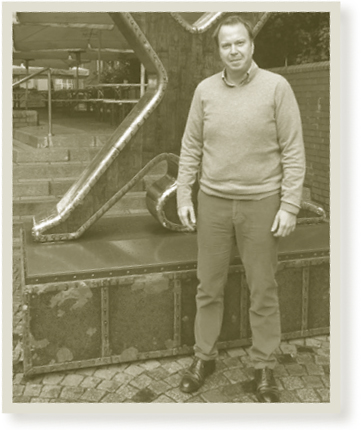

The Schnitzler family has owned Uerige since Christa and Josef purchased it in 1976. Now their son Michael runs the show.

The first stop is the wide, flat, cool ship where it will spend an hour to an hour and a half, depending on the ambient temperature. The boiling wort will cool to about 122°F in the winter and 150°F in the summer. Since that’s far too warm for yeast, the wort spends another hour and a half dripping over undulating stacks of pipes running with cold water. When it finally collects in the fermenters, it is 68°F, perfect for fermentation.

The incredibly efficient Uerige yeast needs only a day in the open fermenters. I understand this has always been the case, but I wonder if the new fermentation room, lit like a nightclub with blue light to fascinate pubgoers, energizes the yeast. Perhaps because of its efficiency, the yeast produces little in the way of fruity esters even at moderately warm fermentation temperatures. But it is in the conditioning tanks, where the beer rests at icy temperatures for a month, that altbier achieves its elegance and smoothness.

Uerige makes an unfiltered version of its regular alt; it is softer and seems to have even more flavor. The real rarity, though, is its Sticke, a beer wreathed in myth. The name, another word from the local dialect, means “secret.” The brewery’s Marie Tetzlaff explained it to me when we were sipping Sticke from the conditioning tank. “The word sticke means that the brewer in the tradition has made stronger beer—but secretly. It’s kind of a verb that means to do something behind someone’s back. Maybe he put more hops and more malt to make it stronger beer, but the people [weren’t sure]. So they said, ‘Ah, the brewer did something sticke, secret.’” There’s a second meaning, which relates to the beer’s release. It only comes around twice a year, and originally, the brewery didn’t announce when it would be on tap. It was a way to thank regulars and give them something special. Now Uerige announces the dates (the third Tuesdays in January and October) and people flock from not only around Düsseldorf, but from all over the world.

Sticke and an even stronger beer called Doppelsticke are made the same way as the regular alt with two exceptions: They are lagered much longer—eight to ten weeks for Sticke, up to twenty weeks for Doppelsticke—and dry-hopped. This last feature makes Sticke even more rare because dry-hopping is not fully kosher according to the rules of Reinheitsgebot. But alt is an ale, a different beast—Reinheitsgebot was originally a Bavarian law regulating lagers—and dry-hopping Sticke makes it a spicily aromatic beer. After I had sampled the Sticke, brewer Sebastian Degen found some Doppelsticke in the tank that was nearly ready to bottle. It was a hugely creamy beer but more floral than the regular Sticke. At 8.5% ABV, it took the chill out of the cold conditioning room.

I had such a wonderful time visiting the pubs and breweries of Düsseldorf that I wondered how business was. Everywhere we went, pubs were bursting with patrons, even in the cold of October. Michael Schnitzler did not mince his words. “In general, the altbier is in bad condition. The former biggest Düsseldorf breweries, they started twenty or thirty years ago to quit brewing in the town …. [Real estate] prices are so high that everyone says, ‘Come on, it’s not [worth it] to sell beer. Let’s put it out to rent.’ So the breweries were sold to Warsteiner, Anheuser-Busch. So where is the echte Düsseldorfer brauerei, the real Düsseldorf brewery? That’s the problem everywhere.”

Well, not everywhere. Just off the Rhine River, on Burger Strasse in the altstadt is one echte brauerei that still keeps the tradition.